Fig. 2.1

Sections of a magnetic resonance image of a patient with a large uterine fibroid desiring myomectomy. Ultrasound study in this patient could not delineate the endometrium

Fig. 2.2

Magnetic resonance imaging shows small intracavitary myoma

Table 2.1

Halt study

Halt study | Intramural | Subserosal | Submucosal | Transmural | Combination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Laparoscopic ultrasound | 386 | 184 | 110 | 27 | 89 |

Magnetic resonance imaging | 292 | 121 | 80 | 16 | 22 |

Transvaginal ultrasound | 197 | 92 | 42 | 23 | 33 |

2.1.2 GnRHa Pretreatment

A subject of some discussion has been whether or not pretreatment with a GnRHa before laparoscopic myomectomy is beneficial. Some advocate the potential benefit of shrinkage in size of the fibroids with GnRHa pretreatment and on hemostasis [4], whereas others have been concerned with a blurring of the cleavage plane between the myoma and the myometrium [5]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis [6] has clarified the issue that pretreatment with GnRHa does not increase the operative time associated with laparoscopic myomectomy, a finding consistent with the most recent similar Cochrane review [7] related to the topic. Operative time can be thought of as a surrogate for operative ease, which would incorporate several surgical factors including myoma size, hemostasis, and the cleavage plane between the myoma and the myometrium.

Systematic reviews [6, 7] of the three randomized trials on GnRHa pretreatment before laparoscopic myomectomy did demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in intraoperative blood loss (60 mL) and postoperative hemoglobin (1.15 g/dL). It is debatable whether these findings have clinical significance. It is also interesting to note that there is a discrepancy between the very minimal decrease in intraoperative blood loss and the decrease in postoperative hemoglobin. It is possible, too, that a potential benefit of pretreatment (for 3–6 months) with GnRHa of surgical bleeding is outweighed by the adverse effects of cost and the delay in receiving treatment. This discrepancy may be attributable to an inaccurate estimate of intraoperative blood loss but also may be because of continued postoperative bleeding or oozing. If the latter is true, pretreatment with GnRHa may have a benefit on reducing peritoneal inflammation and postoperative adhesion formation given less postoperative blood loss. Further multicenter and long-term trials are needed.

Table 2.2

Pros and Cons of GnRHa pretreatment

PROS: |

May lead to shrinkage in the size of the fibroids |

Has been shown to produce a significant reduction in intraoperative blood loss (60 mL) |

Pretreatment with GnRHa has not been shown to increase operative time |

Has been shown to lead to significant reduction in postoperative hemoglobin (1.15 g/dL) |

CONS: |

Potential blurring of the cleavage plane between the myoma and the myometrium |

Requires time for pretreatment (usually 3 months) and may lead to delay in surgery |

2.2 Surgical Procedure

Consideration should be given to treating the most symptomatic fibroids first. In the patient with submucosal fibroids and heavy menstrual bleeding, a hysteroscopic resection should be performed first, followed by laparoscopic myomectomy. These procedures may be performed during the same operation.

Attempts should be made to remove all visible or palpable fibroids to prevent future growth and recurrence of symptoms.

Preoperative laboratory work should include a complete blood count, human chorionic gonadotropin type, and screening. For patients with significant anemia or large intramural fibroids, a type and cross of two units of blood should be available. For procedures for which significant blood loss is a risk, the patient may consider having autologous blood available, or the surgeon can arrange to have cell saver technology available.

2.2.1 Consent

Once the surgeon has reviewed all imaging results, the patient should be extensively counseled about the risks of the procedure. Standard risks of bleeding, infection, adhesion formation, laparotomy, transfusion as well as organ injury should be discussed. Additionally, risks inherent in myomectomy, such as myoma recurrence, should be discussed. Up to 25 % of women may require additional surgery in the future for symptomatic myoma recurrence [8]. The risks of possible uterine rupture with future pregnancy and the need for cesarean section birth should be discussed.

Limited studies are available on the risks of uterine rupture. Generally speaking, the risk of rupture during pregnancy or during labor is 2.4 per 1,000 between 29 and 35.5 weeks [9]. To minimize this risk, it is recommended that the pseudocapsules of excised myomas be preserved for uterine anatomic and functional integrity, especially in women desiring future pregnancy. This can be done by limiting the use of diathermocoagulation and excessive suturing [9]. The surgeon may individualize his or her recommendation for delayed conception based on the extent and size of the fibroids. For example, a patient with a large pedunculated myomectomy may only wait 3 months for a procedure, whereas a patient requiring an extensive repair of the myometrium may wait 6 months [10].

2.2.2 Equipment

Needed instruments, sutures, and solutions in the operating room are key to a successful myomectomy. These necessary items include a single tooth tenaculum, myoma screw, and V-Loc suture (V-Loc, Covidien; Dublin, Ireland) or the surgeon’s suture preference. A dilute vasopressin solution of 20 U in 100 mL of normal saline is helpful to decrease intraoperative blood loss [11, 12]. The surgeon should plan a method of morcellation and have needed equipment available.

Table 2.3

Optional equipment

Dilute vasopressin solution |

Red rubber catheter to use as a tourniquet |

Single tooth tenaculum |

Myoma screw |

Suture (polydioxone, polyglactin, or an absorbable barbed suture on a CT 1 or GS 21 needle) |

Morcellator or self-retaining retractor for minimally invasive morcellation (see Fig. 2.11) |

2.2.3 Patient Positioning and Port Placement

The patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position in Allen stirrups, arms tucked, and a Foley catheter is placed. A uterine manipulator that can antiflex and retroflex the uterus is helpful to assist with exposure when suturing. We use the reusable Valtchev uterine manipulator (Conkin Surgical Instruments; Toronto, Canada).

Use of the umbilical port is optimal for the camera, as this is cosmetically most appealing and serves as an excellent site to extend through the base for morcellation. This technique will be described later in this chapter. We typically place a 10-mm trocar in the umbilicus using the Hasson approach and use a 10-mm, 30-degree angled laparoscope. Other options include a flexible laparoscope or a variable-view laparoscope to allow more flexibility in available views. For straightforward fibroids, a 10-mm, zero degree laparoscope can be used. If the uterus extends above the umbilicus, placing the camera port above the level of the umbilicus in the midline may give greater exposure.

Additional port placement may be individualized based on the size and location of the myoma. Depending on the surgeon’s training and preference, three accessory ports are generally needed. Options include placing two 5-mm ports on the primary surgeon’s side and one on the assistant’s side. It is important when placing two ports on the same side to place them at least a hands width (approximately 5–6 cm) apart from each other to prevent instrument clashing. The assistant’s side port must be placed above the level of the uterus, since this is the port will be used to elevate and enucleate the fibroid out of the uterus.

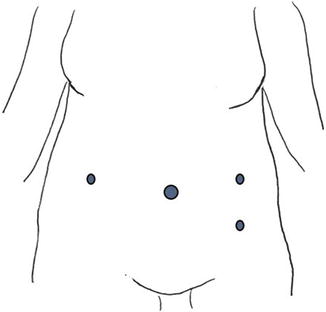

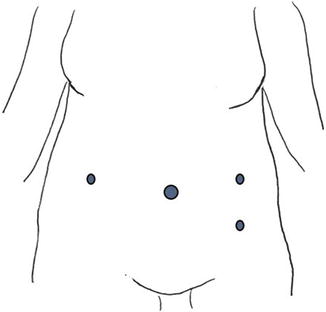

Fig. 2.3

Port placement for most uteri with myomas extending up to the umbilicus

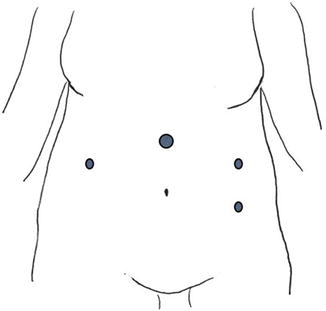

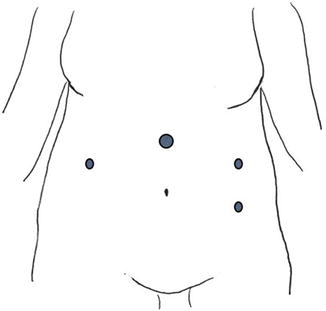

Fig. 2.4

Alternative port placement for large myomas extending above the umbilicus

CT-1 or GS 21 (V-Loc) needles are best for uterine repair and can be introduced and removed through the 10- to 12-mm trocar at the umbilicus. Other options include dragging the needle into the abdominal cavity on the swedge through a 5-mm skin incision. Another choice is replacing the suprapubic 5-mm trocar with a 10- to 12-mm trocar and introducing the needle directly through this port. This larger port site could also then be utilized for a disposable or reusable morcellator. It is important to close the fascia of any port that is 10 mm or larger.

2.3 Surgical Technique

Once pneumoperitoneum and port placement are obtained, the abdominopelvic cavity is explored. The uterus is carefully assessed and a comparison made with its appearance in preoperative imaging. The relationship of the myomas to the fallopian tubes and ovaries is assessed. In uteri with multiple fibroids, the most symptomatic myoma may be targeted first. There may be cases where the uterus must be debulked by removing smaller, less symptomatic fibroids to achieve better access to the primary fibroid. Generally, removing fundal fibroids first will afford greater access to lower uterine segment fibroids.

Formulating a plan for hemostasis is critical. Typically, bleeding from the myometrium adjacent to the myoma is anticipated until the entire defect is closed. The bleeding may be slow but constant. The nature of this slow, steady bleeding may be deceiving. Communication with the anesthesiologist is important to keep an accurate count of blood loss. A dilute vasopressin solution (20 U/100 mL normal saline) can help limit blood loss [9]. The site of injection depends on the type of myoma. For example, a pedunculated myoma should be injected at the myometrial base of the stalk of the myoma. An intramural fibroid can be injected through the uterine serosa, ideally in the plane just inside of the pseudocapsule, creating a “wheel” effect. This technique is more effective than deep myoma injection. With large intramural myomas, the deeper adjacent myometrium toward the base may be injected as it is exposed if excessive bleeding is encountered. Spot cautery with bipolar energy can be helpful for distinct vessels but its use is limited with bleeding from the raw surface of the myometrium. Excessive use of thermal energy for hemostasis is discouraged because this may increase destruction of healthy myometrial tissue and impair uterine healing and functionality [9].

For patients with extremely large intramural myomas (>10 cm) that would require multilayer closure, additional steps may be considered for preventing excessive blood loss. Some authors describe selective use of a laparoscopically placed tourniquet to compress the uterine arteries at the level of the cervix [10, 12]. This technique involves threading a red rubber catheter through bilateral windows created in the broad ligament encircling the cervix. The ends of the red rubber catheter are brought through the lateral trocar skin incisions on contralateral sides, outside of the trocar, and secured with Kelly clamps where they exit the port sites [10].

For women who have completed childbearing, permanent uterine artery occlusion, using clips, suture, or complete transection can be performed. Preliminary studies suggest that this technique can decrease intraoperative blood loss and may also help prevent fibroid recurrence [12].

Table 2.4

Tips for hemostasis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree