Fig. 9.1

Pelvic node dissection templates—limited (LMD), standard (Std), and extended (Ext)

What is considered adequate pelvic lymphadenectomy for bladder cancer and is there a therapeutic benefit in LN positive disease? Smith and Whitmore demonstrated that the obturator and external iliac lymph node regions were the most common sites for lymph node metastases at 74 and 65 %, respectively [11]. Additionally in this study it was found that 19 % of positive lymph nodes were along the common iliac chain. This was one of the first studies indicating that a standard lymph node dissection was likely an inadequate for removal of regionally involved lymph nodes. Leissner et al. performed a study in 447 patients who underwent pelvic lymphadenectomy and found that there was a statistically significant survival advantage in patient who underwent a more extended lymphadenectomy with equal or greater than 16 lymph nodes removed [5]. There was a significant correlation between the number of lymph nodes removed and the 5-year cancer-specific survival in pT1-3 tumors. In a later multicenter study by Leissner et al. that involved 290 patients who underwent radical cystectomy with extended pelvic lymphadenectomy found that approximately 28 % have positive lymph nodes and the percentage of metastases at different sites range from 14.1 % in the right obturator nodes to 2.9 % in the para-caval nodes above the aortic bifurcation [6]. Their analysis found that the incidental LN metastases was 21 % for nodes inferior to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery and 18.6 % at the common iliac and presacral nodes. They also showed that 10 % of primary sites of lymphatic spread were at the common iliac nose, and tumor spread to the contralateral side of the pelvic nodes was also found. They also report reported that 16.5 % of lymph node positive metastases were found between the level of the IMA and the aortic bifurcation suggesting the necessity for dissection of this region especially for the purpose of staging. However, a separate study by Zehnder et al. compared the extended lymphadenectomy data from Skinner’s series at the University of Southern California which included superior boundary of the IMA to the University of Bern with the boundary being the uretero–iliac crossing [12]. The USC group compared to the University of Bern group had a higher number of lymph nodes taken (38 versus 22, p < 0.0001) and a higher incidence of lymph node metastases (35 versus 28 %, p = 0.02). However, patient survival and recurrence was almost equivocal between these two large institutions suggesting no additional survival benefit from dissecting more cranial than the level of the ureteroiliac crossing at the common iliacs. Thus, the cranial extent of the dissection remains controversial in regard to survival.

Many authors have made the argument about the increased potential for staging with ePLND in regard to stratification of patient who may need adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery. However, to date there is no level I evidence that strongly supports adjuvant chemotherapy affecting survival in the postoperative setting. However a small retrospective series from Steinberg et al. that demonstrated that patients with lymph node metastases who received chemotherapy lived six times longer than patient who did not receive chemotherapy (48 versus 8 months, p < 0.0001) [13]. The benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy remains controversial; however, extended staging lymphadenectomy may be important for identifying patients at high risk patients for recurrence. The incidence of patients with nodal positive disease likely increases with a total of number of lymph nodes removed [12]. USC popularized the concept of lymph node density, which was defined as the total number of positive lymph nodes divided by the total number of lymph nodes taken. Lymph node densities greater than 20 % demonstrated an increased risk of death versus patients with a lymph node density less than 20 % (17 versus 43 % 10-year recurrence-free survival) [14]. It has been well established in the literature that the number of lymph nodes that will be reported is dependent on the pathologic processing [15–17]. A number of studies have demonstrated that increased node counts will be reported along with increased positive node detection with the increased number of specimens packet sent [15–17]. There is the potential concern that extended lymph node dissection increases the potential complication rate with radical cystectomy. Brössner et al. performed a prospective study looking at 92 consecutive patients who underwent radical cystectomy with 46 undergoing a standard LND versus 46 undergoing an extended LND. There was no difference in 30-day morbidity between the two groups. The extended lymphadenectomy clearly increases the operative time; however, this is not translated to increase morbidity or mortality in the literature [18]. Nevertheless, the oncologic gains from the extended template must be balanced against the additional time required that may relate to overall anesthetic time and subsequent thromboembolic risk, accumulation of lymphoceles, risk for vascular injury, and temporary or permanent lower extremity edema.

Extended Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection Technique: Making the Transition with Robot-Assisted Platforms

Surgical training for robot-assisted radical cystectomy with extended pelvic lymph node dissection is best rooted in robot-assisted radical prostatectomy [19], first starting with cases that require only a limited node dissection and progressing to an extended template for high risk disease. The latter requires an understanding of the familiar obturator fossa anatomy in which the main task is to retrieve the lymph nodes from under the iliac vein from the distal landmark of the node of Cloquet and proximally to somewhere near the hypogastric artery. Laterally the border is the pelvic sidewall, and inferior is the obturator nerve, which must be preserved. From observing other surgeons and personal experience, it is clear that the distal node of Cloquet is often visible and fairly easy to obtain but likely drains the leg and less often involved with pelvic cancers. However the more proximal tissue in and around the obturator nerve as is passes lateral to the iliac vein is much more difficult to retrieve, and there is tremendous variability in how persistent surgeons are in working for these lymph nodes. These nodes, however, are very close to the hypogastric artery and a common landing site for prostate and bladder cancers.

Expansion of the template to the hypogastric artery zone, as described by Bader et al. [20] requires a more advanced skill set. The obturator fossa is fairly avascular, and the main potential complication is injury to the obturator nerve from blind clipping or errant cutting/coagulating. In the hypogastric template, there are multiple fine arterial/venous branches from the hypogastric and other feeding sources. The surrounding lymph nodes will not lift into the specimen until the vasculature holding them down is controlled with either a bipolar sealant or clip/cut. Furthermore, the exposure of the hypogastric artery requires some work. The peritoneum over the iliac vessels and psoas muscle needs to be divided, and the ureter identified and gently pulled medial—generally in the vicinity of its crossing over the common iliac artery. Within 3–5 cm of the takeoff of the hypogastric artery, the large caliber obliterated artery abruptly turns medial to the bladder. The ureter always passes inferior to this landmark. In prostatectomy, this artery can be preserved, while in cystectomy it must be taken. From this point distally, the hypogastric is a complex structure that dives deep within pelvic spaces, sending out varied patterns of branches medial to the bladder, and distally into the obturator space—some named structures and some not. Dissection along the hypogastric artery at this point occurs for a centimeter or two medially and would stop at the bladder. Lateral to the hypogastric artery, there is ample lymph node tissue present inferior to the obturator nerve all the way to the pelvic sidewall. Again, this region is rich in small caliber vascular branches requiring effective seal. In general, one distinct recommendation for extended pelvic lymphadenectomy for prostate cancer is to limit the lateral/high dissection to the junction between the iliac artery and vein. Thus some external iliac nodes are taken, but the lateral tissue from the artery to the genitofemoral nerve is left alone to decrease the incidence of postoperative lower extremity edema.

Continued evolution of technique from a prostatectomy to radical cystectomy requires expansion of the template. Based upon Bochner et al.’s lymph node mapping study from 2004 [21], we studied our learning curve with this procedure by adopting this template: right and left external iliac, right and left obturator/hypogastric, right and left common iliac, pre-sacral, and para-caval/para-aortic. This map, therefore consists of six paired zones and two midline zones. Initially we performed a protocol with robotic e-PLND to all zones and during the open diversion performed a second look open EPLND. The overall robotic times were a median 117 min (range 89–152) and retrieved a median of 43 nodes (range 19–63). Additional lymph nodes (median 4) were retrieved by second look open, but a majority of zones were completely cleared (67 %) or retrieved non-lymph node tissue (13 %) [22].

Sequence and Exposure

The pelvic lymph nodes can be done first or second. Doing them first leaves the urine drainage intact longer in the case and can setup the pedicles for the cystectomy as second step. The lymph nodes can be organized into 1–2 bags using surgical to separate the different zones. More recently, we have utilized the Anchor Tissue Retrieval System (Anchor Products Company, Addison, IL, USA), which can be reused, however, limiting the extraction to what can fit through a port. We avoid pulling large amounts of unprotected lymph nodes through ports to minimize risk of tumor seeding.

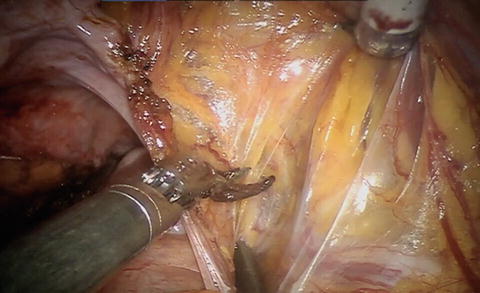

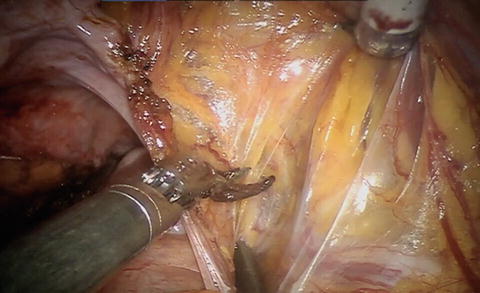

With a lymph node first approach, it is helpful to go ahead and divide the Pouch of Douglas and free up the posterior planes. For a nerve-sparing case, divide/mobilize the seminal vesicles as they will be valuable landmarks for the nerve sparing. To start the nodes, divide the peritoneum over the medial umbilical ligament and then across the iliac vessels and psoas muscle. Leave the midline intact so the bladder is easier to expose at the pedicles—see Video 9.1 and Fig. 9.2.

Fig. 9.2

Division of the peritoneum from the medial umbilical ligament and over the iliac vessels permits identification of the ureter and vessels

Instrumentation

The robotic surgeon utilizes the monopolar scissors, bipolar Maryland, and in the third arm the Prograsp or Cautier. The assistants need a bowel-friendly grasper such as a laparoscopic Debaky and the suction. The position of the assistant varies by surgeon preference, however, if planning a robotic ileal conduit, the technique presented by Castle [23] calls for a left-sided assistant with two 12-mm port access to allow ideal stapling angles to the bowel.

In terms of dissection style, the monopolar scissors is efficient at dividing tissues and sealing very small vessels <2–3 mm. Vessels any larger require a bipolar and larger than 5 mm may require a clip. Most split/roll lymphatics can be simply divided with cautery, however, the proximal and distal extent of dissection should probably be clipped to decreased lymphatic collection, even though the operation is transperitoneal. Cautery use near the obturator nerve will likely induce a muscular contraction and should be avoided.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree