Ripstein Procedure

Jason F. Hall

Helen M. MacRae

Patricia L. Roberts

Introduction

Rectal prolapse is a full thickness protrusion of the rectum outside of the anal canal. It is an uncommon condition affecting an estimated 2.5 per 100,000 population (1). The condition predominantly affects women in the seventh and eighth decades.

Risk factors for the development of rectal prolapse include weak pelvic floor musculature, a deep pouch of Douglas, a redundant rectosigmoid, and lack of fixation of the rectum to the sacrum; nulliparity in women is also associated with prolapse. Other disease and conditions linked to rectal prolapse include connective tissue disorders, especially scleroderma, neurologic diseases, such as spina bifida, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and senility, prior surgery for congenital anomalies, especially imperforate anus, mental illness, and eating disorders, such as bulimia. A history of disordered defecation is often elicited.

Men affected by rectal prolapse tend to be younger than affected women. Rectal prolapse is also recognized in children under the age of 3 years and occurs in equivalent numbers of boys and girls. In young children, it is most often a self-limited condition associated with a diarrheal illness. The prolapse is often mucosal only and resolves with development of the sacral attachments to the rectum. The condition is also associated with cystic fibrosis, especially in Western countries.

The Ripstein procedure and its variations involve a rectopexy with the use of mesh. The Ripstein procedure previously was a common procedure for treatment of rectal prolapse because of its low recurrence rate, and the avoidance of a bowel anastomosis. However, the procedure has largely been supplanted by sigmoid resection and rectopexy or laparoscopic sutured rectopexy. Thus, although the Ripstein procedure and its variations are currently not a common operation for rectal prolapse, it still has specific indications, and should be in the armamentarium of any surgeon who treats rectal prolapse.

The ideal operation for rectal prolapse should have low morbidity and should resolve the anatomic and physiologic abnormalities. Pursuit of this goal has resulted in over 100 procedures described for the correction or amelioration of rectal prolapse (2). These procedures have generally been grouped into two general categories; transabdominal and transperineal approaches. Traditionally, transabdominal approaches have been

used for younger, healthy individuals to minimize recurrence, and transperineal procedures to elderly, frail populations, minimizing morbidity. It is difficult to make firm recommendations regarding the appropriateness of each technique for differing patient populations due to the lack of quality data on outcomes (3).

used for younger, healthy individuals to minimize recurrence, and transperineal procedures to elderly, frail populations, minimizing morbidity. It is difficult to make firm recommendations regarding the appropriateness of each technique for differing patient populations due to the lack of quality data on outcomes (3).

In the past, the Ripstein procedure was the abdominal procedure of choice for rectal prolapse. Currently, it is primarily used for patients in whom an abdominal procedure is indicated, but resection is either not indicated (those patients with no constipation), or where an anastomosis may be at high risk. The Ripstein procedure may also be undertaken in patients with recurrent rectal prolapse after other repairs. Patients who have failed previous perineal approaches, especially the Altemeier approach, may also be good candidates for a Ripstein type repair. In these patients, concern with the vascular supply may preclude an abdominal resection. Suture rectopexy is another option in these patient groups, with little evidence demonstrating superiority of one procedure over the other, but more long term data for the Ripstein procedure.

Ripstein first described an anterior sling rectopexy in 1952 (4). The procedure is typically performed through a transabdominal incision but can also be completed laparoscopically (5). Contraindications to the Ripstein procedure include the presence of medical comorbidities that would preclude a successful abdominal operation. Sepsis or fecal spillage at the time of surgery are also contraindications. A relative contraindication would be patients with preoperative constipation as the Ripstein procedure has increased the reported postoperative rates of constipation (6).

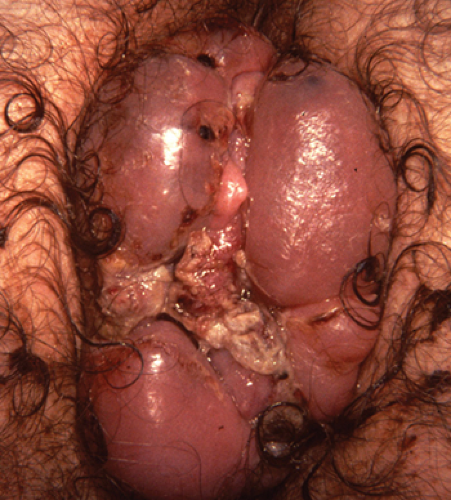

The initial assessment begins with the demonstration of rectal prolapse in the surgeon’s office. If the prolapse cannot be demonstrated on the exam table, the patient should be asked to strain on the toilet. The main differential diagnosis is prolapsing hemorrhoidal disease. Patients with rectal prolapse will generally have tissue with concentric prolapsing folds (Fig. 57.1), while patients with hemorrhoidal disease will have radial folds between the columns of Morgagni (Fig. 57.2). In full thickness rectal prolapse, two distinct walls of the rectum are palpable.

If a full thickness rectal prolapse cannot be demonstrated, defecography can be performed to assess for prolapse. Internal intussusception is a common finding on defecography, and not generally an indication for surgery.

Digital rectal examination is performed to assess resting and squeeze pressures. Patients with rectal prolapse often have a patulous anus and weak anal sphincters. Women should be assessed for rectocele, enterocele, or other pelvic prolapse. Combined repair of other pelvic floor disorders, such as uterine and vaginal prolapse or cystocele are carried out with a multidisciplinary team. Approximately 5% of patients have an associated solitary rectal ulceration. This condition is believed to result from repeated mucosal trauma and resultant ischemia and generally occurs in the anterior rectum. It may be confused with rectal cancer and biopsy can easily confirm the diagnosis.

Up to 50% of patients with rectal prolapse suffer from fecal incontinence. This is thought to be secondary abnormalities in rectal compliance and distention (4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree