Chapter 23 Zachary L. Smith, MD; Thomas J. Guzzo, MD, MPH Retroperitoneal anatomy is a topic in which all practicing urologists should be well versed. Multiple disease entities, both urologic in origin and otherwise, occur in the retroperitoneum and are treated by urologists. The retroperitoneal space is bounded anteriorly by the posterior parietal peritoneum, superiorly by the diaphragmatic reflection, inferiorly by the pelvic diaphragm, and posteriorly by the muscles of the body wall. Anatomic structures from virtually every organ system lie within or traverse the retroperitoneum. This includes major vascular structures such as the aorta and inferior vena cava (IVC) and many of their critical branches. Large nerve plexuses associated with the great vessels, including the celiac, hypogastric, and sacral plexuses, can all be found in the retroperitoneum. Portions of the gastrointestinal tract, including the pancreas and portions of the duodenum and colon, lie within the retroperitoneum. Finally, multiple structures specific to the practice of urology are found in the retroperitoneum, including the kidneys, adrenal glands, and ureters. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis is an uncommon entity that generally affects adults between 40 and 60 years of age. Men have a two to three times higher incidence than women. Children and adolescents are rarely afflicted. Classically, idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis appears as a dense mass in the center of the retroperitoneum, usually at the L4 to L5 vertebral level. It can envelope the great vessels and extend from the aortic bifurcation superiorly to the renal pedicles and laterally beyond the psoas muscle. The inflammatory process can involve almost any retroperitoneal structure, and involvement outside of the retroperitoneum has occasionally been observed. There are many well-documented causes of retroperitoneal fibrosis (Table 23-1) and a thorough evaluation must be completed before the diagnosis of idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis can be made. It is paramount to exclude a primary or metastatic malignancy as the cause of retroperitoneal fibrosis. Table 23-1 Causes of Retroperitoneal Fibrosis LSD, Lysergic acid diethylamide; UTI, urinary tract infection. Retroperitoneal fibrosis can present with a variety of clinical signs and symptoms, depending on the degree of fibrosis and the organs affected. Symptoms generally begin insidiously, often starting out as vague complaints. Patients can present with abdominal and flank pain, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, nausea, or vomiting. Patients may initially present in renal failure secondary to ureteral obstruction. With such a variety of symptoms and presentations, a high index of suspicion is needed to not overlook the diagnosis of retroperitoneal fibrosis. Multiple imaging modalities are useful in the diagnosis of retroperitoneal fibrosis. Classically, the triad of proximal hydroureteronephrosis, medial ureteral deviation, and extrinsic compression of the ureters was noted on intravenous pyelography; however, this imaging modality is used less frequently now. Patients presenting with an elevated creatinine level are often initially evaluated with ultrasonography or with a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan. Noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis allows for visualization of the extent of fibrosis; however, in patients with normal creatinine levels, CT scanning with intravenous contrast permits further evaluation of lymphadenopathy, fibrosis, and possible malignancy. Laboratory tests are nonspecific for the diagnosis of retroperitoneal fibrosis. As in many inflammatory conditions, erythrocyte sedimentation rates and gamma globulin levels are often elevated. In patients presenting with acute renal failure and bilateral obstruction, decompression of the urinary tract and restoration of metabolic homeostasis are a must prior to definitive treatment of the retroperitoneal fibrosis. This can usually be done with ureteral stenting, but in cases in which stent placement fails or it is unsafe to give a general anesthetic, percutaneous nephrostomy tubes should be placed. Once an acute obstruction has been relieved or in the patient presenting without acute renal failure, care must be taken to rule out a primary or metastatic malignancy as the cause of retroperitoneal fibrosis prior to instituting definitive therapy. Should any ambiguity of diagnosis remain following a complete workup, a biopsy should be performed to definitively rule out malignancy. This may be carried out via an open, laparoscopic, or percutaneous route depending on the disease location and the patient’s abdominal anatomy. First-line treatment for idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis can be either medical or surgical, depending both on physician and patient preference. Medical therapies for retroperitoneal fibrosis include glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive therapies. Glucocorticoids have been used with variable success in the literature. No standardized dosing schedule exists, but treatment should not be abandoned early because regression of the fibrotic plaque can be seen up to 20 months after steroid therapy. Typically, patients are treated with 1 to 2 months of high-dose steroids and then slowly tapered down over the remaining treatment time. Immunosuppressant therapy has been reported both in combination with glucocorticoid treatment and as a single-line therapy. There are published reports of success with azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, penicillamine, and mycophenolate mofetil. Should medical therapies fail or not be the desire of the patient, surgical exploration with ureterolysis can be performed. Preoperative ureteral stent placement greatly aids in ureteral dissection. At the time of surgical exploration, deep biopsies should be performed to rule out any undiagnosed malignancy. Once the ureters are completely freed of the fibrotic plaque, they can be intraperitonealized or wrapped with omentum to ensure surgical success. Regardless of whether the disease process is unilateral or bilateral, a bilateral ureterolysis should be performed. Postoperative steroid therapy is often used in an attempt to prevent recurrence. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage is a rare event and can occur in a wide variety of age groups depending on etiology. The causes of retroperitoneal hemorrhage are numerous (Table 23-2). When the bleeding is renal in origin, it has been classically referred to as Wunderlich syndrome. After further workup, this is frequently found to be the initial presentation of a renal angiomyolipoma, which is, in fact, the most common cause of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Patients may present with a variety of symptoms, including back, flank, abdominal, hip, or upper thigh pain. Physical examination may be significant for flank ecchymosis, hypotension, hypovolemic shock, or gross hematuria. Cross-sectional radiographic imaging (usually CT) is most useful in documenting the possible cause and extent of the bleed. Patients should be resuscitated with intravenous fluids and/or blood transfusions as needed. Any anticoagulant medications should be discontinued in the acute setting and any specific coagulopathies treated and reversed. Patients can be monitored with serial imaging to evaluate for resolution of the hematoma and bleeding. In cases in which conservative therapy fails to stabilize the patient, angiography with selective embolization of active bleeding vessels can be performed. Retroperitoneal exploration should be approached with caution because it often results in massive blood loss and, when bleeding is renal in origin, nephrectomy. Repeat imaging should be obtained after complete resolution of the hematoma to rule out malignancy as a cause of the spontaneous bleeding. Pelvic lipomatosis is a benign condition in which an excessive deposition of mature unencapsulated fat is in the pelvic retroperitoneum. The etiology of pelvic lipomatosis is unknown. It is most common in the 20- to 50-year age range and occurs predominantly in men, with African American men having the highest incidence. Obesity is described as a common association. Fifty percent of patients with pelvic lipomatosis will present with voiding dysfunction, including urinary frequency, dysuria, nocturia, and suprapubic tenderness. Constipation may also be a presenting feature. Physical exam is nonspecific, but a suprapubic mass may be palpated. Hypertension is present in a significant proportion of these patients as well as azotemia due to extrinsic compression of the ureters. Cystitis glandularis, cystitis cystica, and cystitis follicularis have been observed in association with pelvic lipomatosis in as high as 75% of patients in some series. This situation should merit special attention from urologists because cystitis glandularis is a potential premalignant lesion of bladder adenocarcinoma. Pelvic lipomatosis has a classic “pear-shaped” or “teardrop-shaped” bladder on intravenous urogram. The upper tracts can range from normal to severely dilated, and the distal ureters are typically deviated medially. CT scan can be useful in the diagnosis of pelvic lipomatosis, given its ability to identify fat. Conservative management of pelvic lipomatosis includes weight reduction and routine radiographic evaluation to monitor for upper tract deterioration. In patients who develop worsening hydronephrosis or progressive azotemia, urinary tract decompression should be performed. Ureteral stenting, nephrostomy tube placement, ureteral reimplantation into the bladder dome, and urinary diversion have all been employed in this setting. Debulking of pelvic fatty tissue has also been reported with success but is technically difficult and not without potential significant complications, including large blood loss and bowel and urinary tract injury.

Retroperitoneal Tumors and Retroperitoneal Fibrosis

Retroperitoneal anatomy

Benign diseases of the retroperitoneum

Retroperitoneal fibrosis

Drugs

Methysergide

Beta-blockers

Ergot alkaloids

Haloperidol

Reserpine

Phenacetin

Methyldopa

LSD

Amphetamines

Traumatic

Hemorrhage

Urinary extravasation Postsurgical

Malignancies

Primary retroperitoneal tumors

Metastatic retroperitoneal tumors

Carcinoid retroperitoneal tumors

Chemicals

Asbestos

Talcum powder

Avitene

Iatrogenic

Radiation

Infections

Chronic UTI

Tuberculosis

Gonorrhea

Syphilis

Inflammatory processes

Endometriosis

Sarcoidosis

Collagen vascular disease

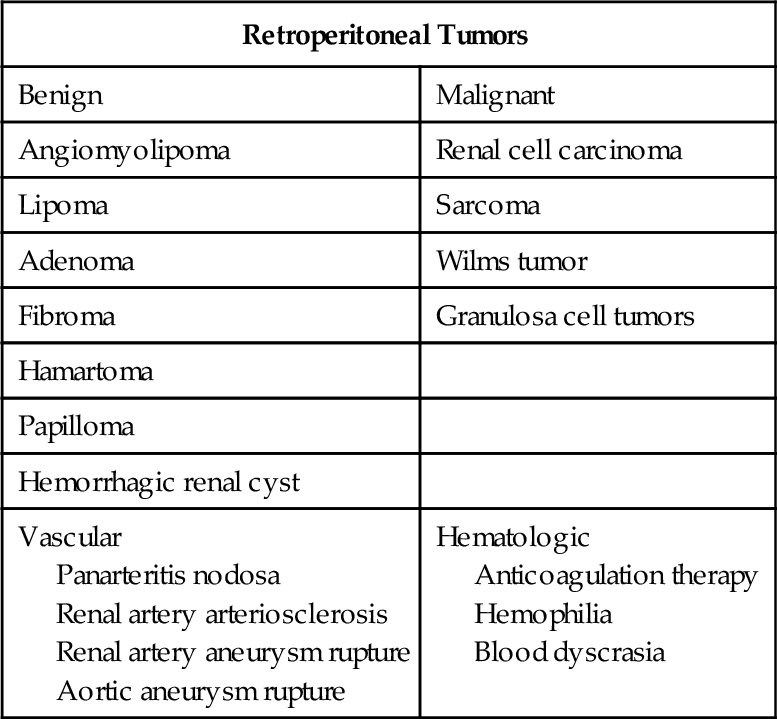

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage

Pelvic lipomatosis

Myelolipoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree