Rectovaginal and Rectourethral Fistula

Paula I. Denoya

Marvin L. Corman

Mothers love their children more than fathers, because parenthood costs the mothers more trouble.

—Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics IX, vii

▶ RECTOVAGINAL FISTULA

Anovaginal or rectovaginal fistula is not usually a manifestation of anal fistula because it is rarely a consequence of cryptoglandular infection. The condition most commonly occurs following trauma, especially obstetric injury. Venkatesh and colleagues studied the incidence of complications following vaginal delivery in 20,500 women.80 Five percent of all normal deliveries resulted in episiotomy-associated third- and fourth-degree lacerations (Figure 15-1). Of the fourth-degree lacerations, 10% disrupted after primary repair (Figure 15-2). In addition to obstetrically related causes, other etiologic factors related to the development of rectovaginal fistula include the following:

Infiammatory bowel disease—the second most frequent cause (Figure 15-3)

Carcinoma

Radiation

Diverticulitis Foreign body

Penetrating trauma

Infectious processes

Congenital anomalies

Pelvic, perineal, and rectal surgery, especially vaginal hysterectomy and low anterior resection

Anorectal eroticism

Ergotamine induced54

Symptoms and Classification

Patients usually complain of passage of flatus, feces, or pus from the vagina. Depending on the etiology, location, extent, and associated injury, the woman may also have difficulty with the control of flatus and feces per rectum.

Although there is no official classification scheme for rectovaginal fistulae, a commonly used approach is to base categorization on the location of the rectal opening: anal, low rectal, and high rectal. The equivalent gynecologic classification is low vaginal, midvaginal, and high vaginal. The location of the fistula is important because it will determine the operative approach.

A low fistula is usually readily apparent on inspection or upon anoscopy. One usually has little difficulty in identifying the tract and passing a probe, but careful assessment of the tone and contractility of the muscle above the fistula should be made. A midrectal (midvaginal) fistula is also relatively easy to visualize, particularly when one attempts to pass a probe from vagina to rectum. A high fistula may be quite difficult to diagnose, especially if the opening is small. This type is usually a complication of diverticulitis or of hysterectomy. It may also develop as a consequence of an anastomotic leak or staple injury following low anterior resection (Figure 15-4). This type of fistula may originate from the colon, rather than the rectum.

Evaluation

Physical examination should include both rectal and vaginal evaluations. Proctosigmoidoscopic examination and gastrointestinal contrast studies may be indicated, especially if there is doubt concerning the origin of the fistula. With

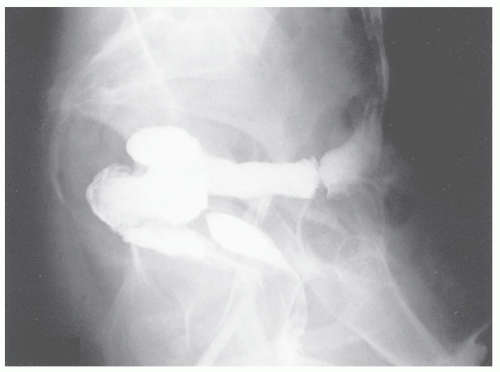

high fistulas, proctosigmoidoscopic examination seldom will demonstrate the opening, but gentle probing at the apex of the vagina will often identify the defect. Barium enema examination may show opacification of the vagina (Figure 15-5). A biopsy should be performed if the fistula is secondary to radiation injury in order to determine the presence or absence of tumor.

high fistulas, proctosigmoidoscopic examination seldom will demonstrate the opening, but gentle probing at the apex of the vagina will often identify the defect. Barium enema examination may show opacification of the vagina (Figure 15-5). A biopsy should be performed if the fistula is secondary to radiation injury in order to determine the presence or absence of tumor.

If the patient’s symptoms are characteristic, but the surgeon is unable to confirm a fistula by one of the foregoing means, there are two other approaches worth attempting. One procedure is to place the patient in the lithotomy position and insert a proctoscope in the rectum. With the woman in a slight Trendelenburg position, the vagina is filled with warm water. Air is then insuffiated through the proctoscope; if bubbles are seen in the vagina, the diagnosis is confirmed. Another alternative is to give the patient a methylene blue small retention enema and leave a tampon in the vagina. The tampon is removed after 1 hour to see whether the blue color appears on it.

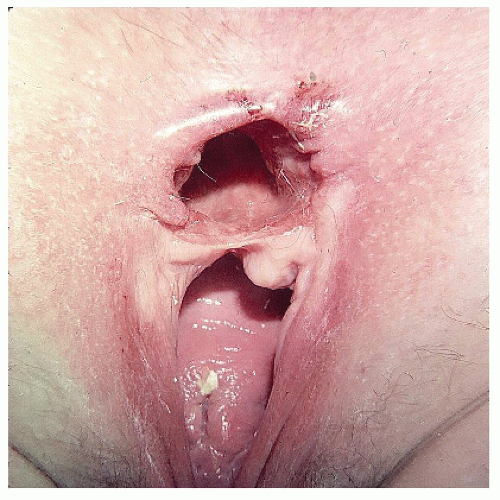

FIGURE 15-2. Cloacal-like defect, a consequence of vaginal delivery of a large infant, a third-degree laceration, and breakdown of the repair. |

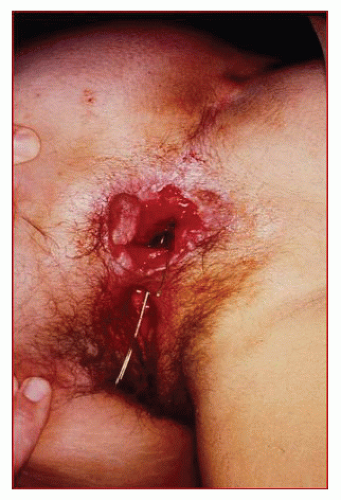

FIGURE 15-3. Rectovaginal fistula secondary to Crohn’s disease. Note the marked disruption of the anal architecture. |

Depending on the origin of the fistula, it may be appropriate to evaluate the proximal colon before definitive repair. This is usually readily accomplished by means of either colonoscopy or barium enema examination. Occasionally, however, it may be difficult to advance the endoscope above the fistula site, and contrast may preferentially pass completely out of the vagina. Under these circumstances, a combination of guidewire passage of the instrument and placement of a Foley catheter above the communication will facilitate proximal evaluation.70

Yee and coworkers reviewed their experience with endoanal ultrasound in patients with rectovaginal fistulas in order to define what role this modality has in preoperative assessment.84 Although the authors believed that noncontrast ultrasound was not helpful for evaluation, they recommended its

use in order to identify occult sphincter defects. The primary purpose, therefore, is to alert the surgeon to consider performing a sphincter reconstruction, which greatly improves successful repair in patients with sphincter defects.76

use in order to identify occult sphincter defects. The primary purpose, therefore, is to alert the surgeon to consider performing a sphincter reconstruction, which greatly improves successful repair in patients with sphincter defects.76

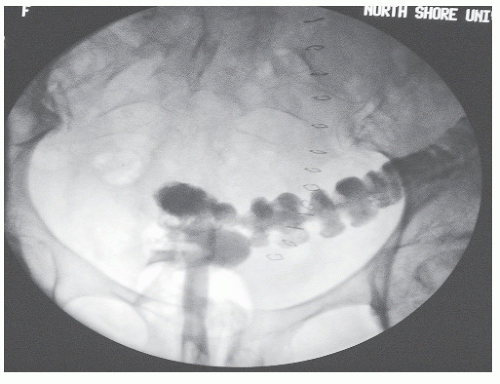

FIGURE 15-4. Barium enema reveals contrast material in the vagina as a consequence of the stapling device incorporating a portion of the posterior vaginal wall. |

FIGURE 15-5. Rectovaginal fistula following hysterectomy. A barium enema demonstrates contrast material in the vagina. |

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used to identify the presence of an occult fistula and to assess the integrity of the anal sphincter muscles. In a retrospective study, MRI was able to detect 100% of anal canal internal openings and 95% of vaginal openings. MRI was also able to identify secondary fistula tracts, abscesses, and sphincter defects.17

Treatment

As suggested, the treatment of rectovaginal fistula depends on the location and the cause. High rectovaginal fistulas are generally approached transabdominally and involve a bowel resection if colon or rectal disease precipitated the communication. If the fistula occurred secondary to hysterectomy, it may suffice to separate the bowel from the vagina; close the opening; and interpose omentum, a peritoneal flap, or fascia. For midvaginal and low rectovaginal fistulas, numerous operative approaches have been advocated, including transvaginal, perineal, transanal, and transsphincteric. One operation that should rarely be considered, however, even for anovaginal or introital fistulas, is simple fistulotomy. Dividing the perineum, even for a relatively superficial fistula, will inevitably cause some degree of incontinence (see Chapter 16) unless a concomitant sphincteroplasty is accomplished to repair any divided sphincter.60 The following summarizes the various operative alternatives:

Operations for Rectovaginal Fistula

Perineal | ||

Fistulotomy alone (placed here for completeness—see previous comment) | ||

Fistulotomy with muscle repair | ||

Anoplasty | ||

Interposition (e.g., bulbocavernosus-labial flap [Martius]) | ||

Transanal | ||

Repair in layers | ||

Repair in layers with sliding flap | ||

Anterior rectal wall | ||

Internal sphincter | ||

Transsphincteric (Mason) | ||

Repair in layers | ||

With sliding vaginal flap (Warren) | ||

With interposition | ||

Abdominal | ||

Simple closure | ||

With interposition | ||

Resection (low anterior, pull-through, abdominosacral, coloanal) | ||

With interposition | ||

Colostomy | ||

The following discussion is confined to low-level and midlevel fistulas. Operations that require an abdominal approach are similar to those performed for other conditions; these are discussed in Chapters 23 and 24.

Most surgeons prefer to place the patient on a mechanical bowel preparation as if for colon resection. This includes a vigorous laxative 1 day before and a tap water enema the morning of surgery until the returns are clear. Others suggest that no cleanout is required, but even if there is no demonstrable increase in septic complications or breakdown of the repair, few enjoy wallowing in stool. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are also suggested within one-half hour prior to incision time. A Foley catheter should be inserted before surgery and kept in place as long as is reasonable or convenient. Standard vaginal antiseptic preparation should also be performed at the time of surgery.

Techniques for Repair of Anovaginal and Low Rectovaginal Fistulas

Any attempt at repair must primarily address the anal or rectal opening, even though the fistula may have arisen from a vaginal source (e.g., obstetric trauma). Many surgeons and

all gynecologists prefer to repair a rectovaginal fistula using the transvaginal approach.73 This is not recommended because the high-pressure zone is in the rectum. If the repair of the rectal opening is satisfactorily accomplished, it is not even necessary to deal with the vagina. Conversely, no matter how meticulous the technique is when performed through the vagina, if the rectal closure does not remain secure, failure will result.

all gynecologists prefer to repair a rectovaginal fistula using the transvaginal approach.73 This is not recommended because the high-pressure zone is in the rectum. If the repair of the rectal opening is satisfactorily accomplished, it is not even necessary to deal with the vagina. Conversely, no matter how meticulous the technique is when performed through the vagina, if the rectal closure does not remain secure, failure will result.

With an anal canal or low-rectal fistula occurring as a consequence of an obstetric injury, the ideal choice is to perform a perineal operation with a concomitant anoplasty and sphincteroplasty (see Chapter 16). The condition is usually the result of anterior displacement of the rectum (i.e., the anal opening is abnormally close to the vagina; see Figures 16-50,16-51,16-52,16-53,16-54,16-55,16-56,16-57,16-58,16-59 and 16-60). Most of these patients will have a concomitant anterior sphincter defect. Many will have significant impairment for the control of feces even if they

do not actually have a rectovaginal fistula. To effect a satisfactory repair, the surgeon should reconstruct the perineal body, and to accomplish this, an anoplasty is preferred.15,63 The operative technique for this procedure is discussed in Chapter 16.

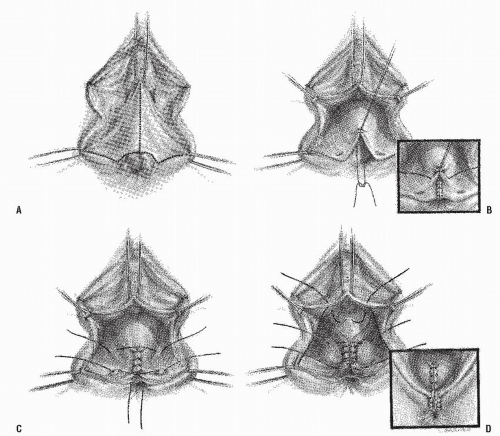

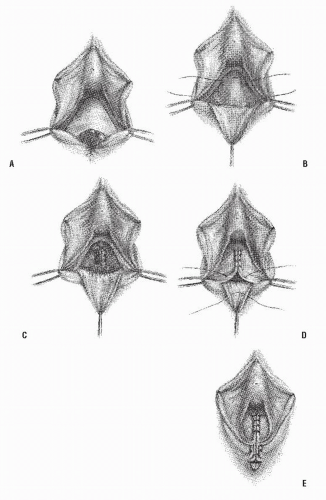

Numerous other approaches to the management of this type of fistula have been described.5,6,7,24,27,29,37,59,63 In general, gynecologists prefer a transvaginal repair—excising or dividing the fistula tract, closing the defects in the rectal and vaginal walls, and repairing the perineum. Three methods of transvaginal repair are illustrated in Figures 15-6,15-7 and 15-8.

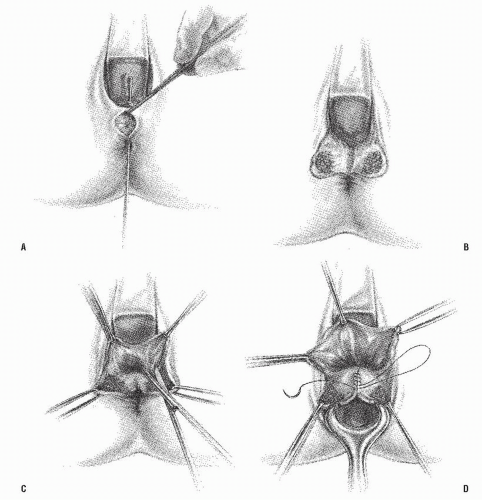

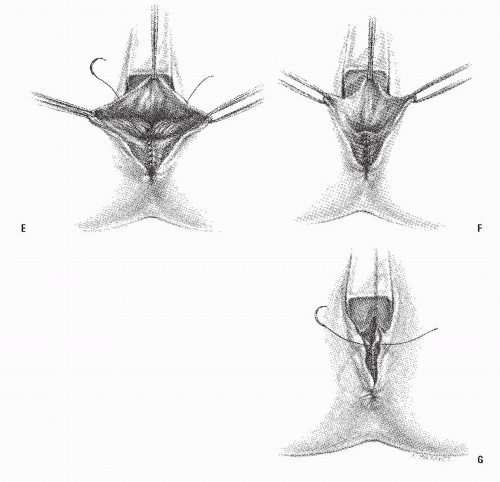

In recent years, surgeons have begun selectively to employ the endorectal advancement flap technique to repair anal and low-rectal fistulas.36,71 This is the same principle described in Chapter 14 for fistula-in-ano. In brief, a mucosal flap is raised, which starts distal to the internal opening. The base should be twice as wide as the apex of the flap and should

extend at least 4 cm proximal to the internal opening in order to allow a tension-free and well-vascularized repair. The flap is mobilized distally to cover the fistula opening and the excess, including the internal opening, is trimmed off. Repair is accomplished using absorbable sutures. The vaginal opening should remain open to allow for drainage. This operation is more likely to be successful for low rectovaginal fistulas than for anovaginal fistulas, however. Berman advocates a sleeve advancement technique for complicated anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas (see Figure 14-43).6 This approach is believed to be particularly useful for individuals in whom the fistulas encompass an extensive portion of the anal or rectal wall or in those with multiple internal openings. The transanal approach with endorectal advancement flap has become the most popular method for treating this complication today.30,33,36,51,59,68 Kodner and colleagues reported their

experience on 107 individuals who underwent this technique for rectovaginal and other complicated anorectal fistulas.36 Their experience is summarized in Table 15-1.

extend at least 4 cm proximal to the internal opening in order to allow a tension-free and well-vascularized repair. The flap is mobilized distally to cover the fistula opening and the excess, including the internal opening, is trimmed off. Repair is accomplished using absorbable sutures. The vaginal opening should remain open to allow for drainage. This operation is more likely to be successful for low rectovaginal fistulas than for anovaginal fistulas, however. Berman advocates a sleeve advancement technique for complicated anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas (see Figure 14-43).6 This approach is believed to be particularly useful for individuals in whom the fistulas encompass an extensive portion of the anal or rectal wall or in those with multiple internal openings. The transanal approach with endorectal advancement flap has become the most popular method for treating this complication today.30,33,36,51,59,68 Kodner and colleagues reported their

experience on 107 individuals who underwent this technique for rectovaginal and other complicated anorectal fistulas.36 Their experience is summarized in Table 15-1.

Persistence of the fistula or recurrence developed in 17 patients (16%). Ultimately, the overall success rate in excess of 90% for this complicated group of patients, with the avoidance of fecal diversion, even on a temporary basis, is excellent.

The University of Minnesota group initially reported 91% success with 35 patients.59 However, a later publication involving 81 patients noted that this was reduced to 83%.40 The Cleveland Clinic group observed a 77% success rate for this procedure.33 The primary factor as noted in another publication from the same institution that adversely affected results was Crohn’s disease.71 Wise and colleagues performed endorectal advancement flaps in 40 women, with

the addition of sphincteroplasty or perineal body reconstruction in 15.83 Those who underwent the combined procedures were continent, whereas seven of those who had not undergone either sphincteroplasty or perineal body reconstruction, in addition to the endorectal advancement flaps, reported impairment for control. It appears, therefore, that the importance of perineal body reconstitution is justified (see Chapter 16). MacRae and coworkers, reporting from Toronto, caution that persistence of a rectovaginal fistula after failed repair should not be managed by advancement flap.41 In essence, they recommend that the patient has one shot at this approach. If it does indeed fail, another option should be selected. Watson and Phillips, reporting from St. Mark’s Hospital in the United Kingdom, experienced overall success in all but 3 of their 26 patients with rectovaginal fistula.82 However, the authors cautioned that this result obscures a high early failure rate in 5 of 12 patients who underwent a transanal advancement flap. They also employed a temporary stoma in 11 individuals.

the addition of sphincteroplasty or perineal body reconstruction in 15.83 Those who underwent the combined procedures were continent, whereas seven of those who had not undergone either sphincteroplasty or perineal body reconstruction, in addition to the endorectal advancement flaps, reported impairment for control. It appears, therefore, that the importance of perineal body reconstitution is justified (see Chapter 16). MacRae and coworkers, reporting from Toronto, caution that persistence of a rectovaginal fistula after failed repair should not be managed by advancement flap.41 In essence, they recommend that the patient has one shot at this approach. If it does indeed fail, another option should be selected. Watson and Phillips, reporting from St. Mark’s Hospital in the United Kingdom, experienced overall success in all but 3 of their 26 patients with rectovaginal fistula.82 However, the authors cautioned that this result obscures a high early failure rate in 5 of 12 patients who underwent a transanal advancement flap. They also employed a temporary stoma in 11 individuals.

Techniques for Repair of Midrectal Fistula

A midrectal (i.e., midvaginal) fistula is the most difficult type of gynecologic/intestinal fistula to repair satisfactorily. Fistula in this location is often a consequence of concomitant Crohn’s disease, of tumor, of radiation injury, and of trauma (including obstetric and surgical). A theoretically simple approach would be to convert the fistula to that of a “fourthdegree laceration.” However, this would of necessity require division of the entire sphincter mechanism. Although this can certainly be accomplished, and it will provide excellent exposure indeed, the risk of breakdown and fecal incontinence should stay the surgeon’s hand. In patients who

already have impaired continence due to sphincter injury, performing a perineoproctotomy may be considered to allow adequate access to both the fistula tract and the sphincter defect. Given reported 32 operative repairs for rectovaginal fistula that were undertaken by 16 surgeons.24 In 10 cases, the entire perineal body was incised, converting the fistula into a complete laceration; this laceration was then repaired in layers. Primary healing took place in all patients. Other procedures were less successful, but the reasons may have had more to do with the level of the fistula and with the underlying pathology than with the method employed. In a retrospective study of 87 patients, Hull and coworkers reported similar success in obtaining healing of the fistula by rectal advancement flap or perineoproctotomy (62% vs. 78%, P = .1), but improved outcomes relating to fecal continence (P < .001) and sexual function (P = .04).31

already have impaired continence due to sphincter injury, performing a perineoproctotomy may be considered to allow adequate access to both the fistula tract and the sphincter defect. Given reported 32 operative repairs for rectovaginal fistula that were undertaken by 16 surgeons.24 In 10 cases, the entire perineal body was incised, converting the fistula into a complete laceration; this laceration was then repaired in layers. Primary healing took place in all patients. Other procedures were less successful, but the reasons may have had more to do with the level of the fistula and with the underlying pathology than with the method employed. In a retrospective study of 87 patients, Hull and coworkers reported similar success in obtaining healing of the fistula by rectal advancement flap or perineoproctotomy (62% vs. 78%, P = .1), but improved outcomes relating to fecal continence (P < .001) and sexual function (P = .04).31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree