Anal Fistula

Alex Jenny Ky

Emily Steinhagen

Bertram: What is it, my good lord, the King languishes of? Lafew: A fistula, my lord.

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE: All’s Well That Ends Well, 1.1.37

A fascinating narrative of Shakespeare and the literary history of anal fistula has been written by Cosman.44

▶ HISTORY

Anal fistula is a condition that has been described virtually from the beginning of medical history. Hippocrates, in about 430 BCE, suggested that the disease was caused by “contusions and tubercles occasioned by rowing or riding on horseback.”4 He was the first person to advocate the use of a seton in treatment (from the Latin seta, a bristle) “taking a very slender thread of raw lint, uniting it into five folds of the length of a span, and wrapping them round with a horse hair.”4 Numerous commentaries have been written on the historical implications associated with anal fistula (see Abu Marwan bio). For example, it has been known that the Sun King, Louis XIV, developed an abscess on February 18, 1685, and by May 2 a fistula had appeared. His doctors tried to treat him, unsuccessfully, with enemas and poultices. Eventually, Charles-François Felix was sent for. Felix recommended an operation, and Louis agreed to it. Felix, however, requested 6 months to prepare himself. He had never done such an operation before, and he needed to practice. He performed the procedure on 75 peasants, men who didn’t actually need the operation. Not all of them lived. On November 18, 1686, at 7 o’clock in the morning, Felix operated on the king. The king was calm, but the surgeon was terrified. The operation was performed without anesthetic. Felix had devised a special curved scalpel and unique retractor. The operation was a success. King Louis was able to sit up in bed within a month, and in another 3 months he was able to ride again. Word of his great courage during the operation spread throughout the court, and some of the nobles took to wearing bandages on their buttocks in the king’s honor. The procedure became known as “the Royal,” and at least 30 nobles asked Felix to perform the same operation on them. They were greatly disappointed when he told them that they didn’t need it. In gratitude for his services, Felix was given a large sum of money, a title, and an estate. The status of surgeons was greatly improved by the event, and in 1731 Louis XV, Louis XIV’s grandson, would establish the Royal Academy of Surgeons. As for Charles-François Felix, he was apparently greatly shaken by his experience. He never touched a scalpel again.

The fascination with anal fistula for more than 2,000 years is manifested by the numerous papers and books on the subject. In fact, Salmon established a hospital in London devoted to the treatment of anal fistula and other rectal conditions— St. Mark’s. Allingham also established his reputation through operations for anal fistula. His book on rectal surgery was published through numerous editions.

It has been said that more surgeons’ reputations have been impugned because of the consequences of fistula operations than from any other operative procedure. Complications of fistula surgery are myriad and include fecal soilage, mucous discharge, varying degrees of incontinence (gas and/or stool), recurrent abscess, and recurrent fistula. In the United States, impairment for bowel control from even a properly performed operation for anal fistula is one of the most frequent reasons in the field of colon and rectal surgery for a patient to pay a visit to an attorney. It is for this reason that the prescient surgeon will make a special effort to explain in detail the attendant risks of the procedure. Moreover, it is critically important to

document the state of that individual’s continence prior to embarking on any procedure. The fact is that no one goes whole to the grave with perfect anal control following surgery if an anal fistula traverses a significant portion of the external sphincter. Clearly, the surgeon who is fortunate enough to have the opportunity to treat the patient initially is the one most likely to effect a cure, to limit morbidity, and to minimize disability.

document the state of that individual’s continence prior to embarking on any procedure. The fact is that no one goes whole to the grave with perfect anal control following surgery if an anal fistula traverses a significant portion of the external sphincter. Clearly, the surgeon who is fortunate enough to have the opportunity to treat the patient initially is the one most likely to effect a cure, to limit morbidity, and to minimize disability.

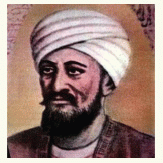

ABU MARWAN ABD AL-MALIK IBN ABI AL-ALA ZUHR (1091-1161)

Also known as Ibn Zuhr or Avenzoar was born in Seville, Spain. He was considered the most renowned physician of Muslim Spain. His most famous book is Al-Taisir in which he introduced the experimental method into surgery, one example being the tracheostomy he performed first on a goat. He was also the first to perform postmortem autopsies and dissections and also contributed to developing feeding tubes and parenteral nutrition. He established surgery as an independent field of medicine by introducing a training course for future surgeons. He was also known for his contributions to the field of pharmacology, neurology, and parasitology. He was one of the first physicians to use anesthesia for surgical procedures. He belonged to a family of physicians who served the Almohad ruler, but due to political turmoil he fell out of favor with the Almoravid ruler. He fled Seville but was imprisoned in Marrakesh. It was during that time when he wrote “Verrucae That Occur in the Stomach” in which he gives the first detailed description of a prisoner suffering from advanced colon cancer. He describes symptoms of diarrhea, bloody stools, palpation of an apple-sized tumor in the lower abdomen, change in stool caliber, cyclical fevers, and cachexia. He attributed his tumor to the diet of his community, which consisted of cured camel meat. In 1147 when the Almohad dynasty conquered Seville, he returned and continued to practice medicine and teaching. He died in 1161 in Seville. (References: Glick TF, Livesey SJ, Wallis F, eds. Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2005; Azar H. The Sage of Seville: Ibn Zuhr, His Time and His Medical Legacy. New York, NY: The American University in Cairo Press; 2008; Azar HA, McVaugh MR, Shatzmiller J. Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar)’s description of a verrucous malignancy of the colon (with an English translation from Arabic and notes on its Hebrew and Latin versions). Can Bull Med Hist. 2002;19(2):431-440; Picture from http://www.nndb.com/people/643/000097352/.) (With appreciation to Hussna Wakily, MD.)

|

FREDERICK SALMON (1796-1868)

Salmon was born in Bath, England. He received his medical education at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital and became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1818. After several years in the General Dispensary, Aldersgate Street, Salmon resigned his position, and in 1835 he opened an institution that was named “The Infirmary for the Relief of the Poor, Afflicted With Fistula and Other Diseases of the Rectum.” After relocation two additional times, it was reopened on April 25, 1854 (St. Mark’s Day)—hence, the adoption of the name St. Mark’s Hospital. Salmon seemed to have more than his share of critics; the following is a quote from an obituary statement that appeared in the British Medical Journal: “How far the course which he took was prompted by difficulties in pursuing an useful and honourable career in a general hospital, where his labours would have been more useful and more instructive, it is now difficult to say. It was, we fully believe, contrary to the best interests both of the profession and of the public; and the success of St. Mark’s Hospital was of unfortunate omen and has since borne bad fruit in encouraging similar enterprises.”

|

▶ SYMPTOMS

The most frequent presenting complaints of patients with an anal fistula are swelling, pain, and discharge. The former two symptoms usually are associated with an abscess when the external or secondary opening has closed or has failed to develop. Discharge may be from the external opening or may be reported by the patient as mucus or pus mixed with the stool. Most patients with an overt fistula have an antecedent history of abscess that drained spontaneously or for which surgical drainage had been performed.

Anal fistula may be confused with suppurative hidradenitis and pilonidal sinus (see Chapter 9). However, they may also occur secondary to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (see later and Chapter 30), anal or rectal carcinoma, tuberculosis, actinomycosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, radiation, trauma, or iatrogenic injury.

▶ CLASSIFICATION

The most commonly referred classification was suggested by Parks and colleagues.137

Intersphincteric | |

Simple low tract High blind tract High tract with opening into rectum High fistula without a perineal opening High fistula with extrarectal or pelvic extension Fistula from pelvic disease | |

Transsphincteric | |

Uncomplicated High blind tract | |

Suprasphincteric | |

Uncomplicated High blind tract | |

Extrasphincteric | |

Secondary to transsphincteric fistula Secondary to trauma Secondary to anorectal disease (e.g., Crohn’s) Secondary to pelvic inflammation | |

Combined Horseshoe | |

Intersphincteric Transsphincteric | |

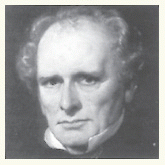

WILLIAM ALLINGHAM (1829-1908)

William Allingham was educated for the profession of architecture at University College, where he gained numerous prizes. He even practiced as an architect, exhibited studies at the exhibitions of the Royal Academy, and obtained honorable mention for a design of a building to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. In this year, however, he decided to abandon architecture for medicine. Entering as a student at St. Thomas’s Hospital, he carried off prize after prize—the Descriptive Anatomy Prize, the Anatomy Prize (1854), the Medicine Prize, the Clinical Medicine President’s Prize, and the Clinical Medicine Treasurer’s Prize (1855). After qualifying in 1855, he volunteered as surgeon in the Crimean War. He was in time to be present at the siege of Sebastopol and to see a vast amount of practical surgery in the most arduous circumstances at the hospitals at Scutari. During a large part of his war services, he was attached to the French Army, which was extremely poorly provided with surgical aid, and there is no doubt that under the strenuous nature of the duties which devolved upon him, Allingham gained the courage and sense of responsibility, which marked him out as a successful operating surgeon from the beginning of his career. After his return home, he was surgical tutor, demonstrator of anatomy, and then surgical registrar at St. Thomas’s Hospital. He set up in practice in 1863 as a consultant at 36 Finsbury Square, EC, but removed to Grosvenor Street, where he soon became a wellknown authority on diseases of the rectum and enjoyed a large practice. In 1871, he published his classical book on Diseases of the Rectum.7 It was accepted at once as an authoritative and inclusive work, although some surgeons differed from the author on points of technique. William Allingham was not attached to the staff of any of the great London hospitals possessing a medical school, but was for many years surgeon to the Great Northern Central Hospital and to St. Mark’s Hospital for Fistula and Diseases of the Rectum. He was also consulting surgeon to the Farringdon General Dispensary and to the Surgical Aid Society, of which, together with some of his relatives and others, he was one of the founders in 1862. He was a member of the Council of the Royal College of Surgeons from 1884 to 1886 and retired from practice in 1894. Allingham was one of the first surgeons in England to specialize in the treatment of diseases of the rectum, out of which he made a considerable fortune. After his retirement, he lived for some time at St. Leonards, and then at Worthing, where he died on February 4, 1908. (Courtesy of Muath Bishawi, MD.)

Although not included in this classic schema, “complex fistula” is defined as other than an intersphincteric or low extrasphincteric fistula. The implication is that they are more difficult to treat than conventional fistulas and, in addition, are associated with increased risk of recurrence as well as a greater likelihood for impairment of control. These fistulas have also been labeled “problematic” by some.1,167 Frenkel proposed a classification based on the level of the fistula: low, mid, and high/complex.57 However, five types of fistulas are generally described by most authors. They are as follows:

Submucous

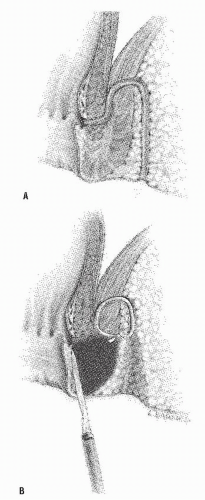

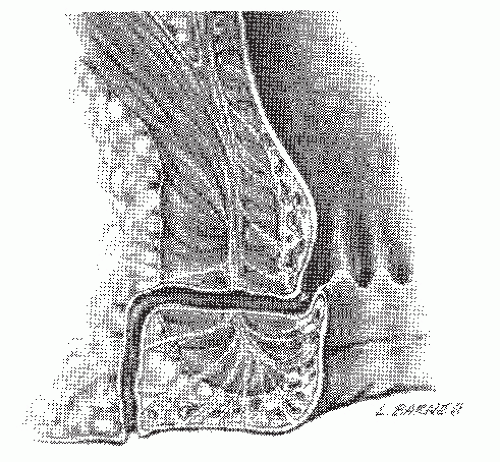

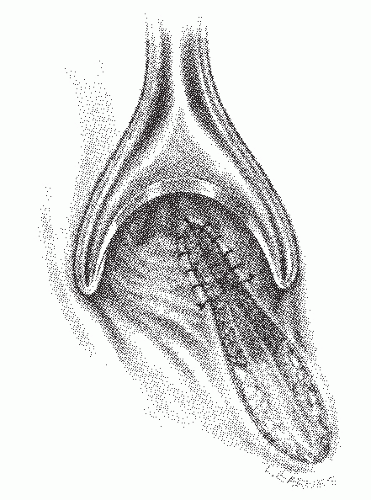

Intersphincteric (Figure 14-1)

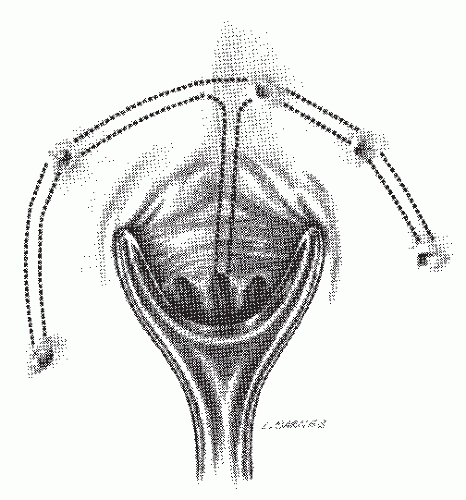

Transsphincteric (Figure 14-2)

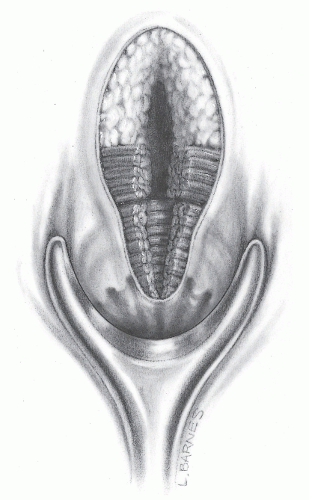

Suprasphincteric (Figure 14-3)

Extrasphincteric (Figure 14-4)

The submucous fistula is a misnomer. See the discussion in Chapter 13.

As its name suggests, an intersphincteric fistula passes through the internal sphincter to the skin. Occasionally, an extension may be observed to proceed cephalad in the intersphincteric plain (i.e., high blind tract), but this has no consequence in one’s therapeutic decision making. It has also been

reported to extend cephalad and present with another opening in the rectum.137 Only the most superficial or subcutaneous portions of the external sphincter may be divided when a fistulotomy is undertaken. Intersphincteric fistulas are the most common type of fistula, with an incidence of 55% to 70%.

reported to extend cephalad and present with another opening in the rectum.137 Only the most superficial or subcutaneous portions of the external sphincter may be divided when a fistulotomy is undertaken. Intersphincteric fistulas are the most common type of fistula, with an incidence of 55% to 70%.

FIGURE 14-1. Intersphincteric fistula. The tract passes through the internal sphincter and in the intersphincteric plane. |

FIGURE 14-2. Transsphincteric fistula. The tract passes through both the internal and external sphincters, into the ischiorectal fossa, and to the skin. |

A transsphincteric fistula passes through both the internal and external sphincters before exiting to the skin. It usually results from an ischiorectal abscess. The level of the tract determines how much sphincter will need to be divided and the risk of impairment for bowel control if a fistulotomy is performed. This type of fistula is observed in 20% to 25% of most series. Occasionally, a supralevator extension of a transsphincteric fistula is identified (Figure 14-5). Treatment requires recognition of this condition, curettage, irrigation, and packing of the supralevator extension. Under no circumstances should the extension be drained into the rectum.

FIGURE 14-4. Extrasphincteric fistula. The internal opening is above the level of the levator ani muscle, and the tract passes to the skin deep to the external sphincter in the ischiorectal space. |

A suprasphincteric fistula was noted by Parks and colleagues to comprise 20% of their series.137 Other series have reported

that this type of fistula is extremely rare and only constitutes approximately 1% to 3% of fistulas.4 The fistula is described as starting in the intersphincteric plane, passing to a supralevator location, and ultimately tracking between the puborectalis and the levator ani muscles to end in the ischiorectal fossa.

that this type of fistula is extremely rare and only constitutes approximately 1% to 3% of fistulas.4 The fistula is described as starting in the intersphincteric plane, passing to a supralevator location, and ultimately tracking between the puborectalis and the levator ani muscles to end in the ischiorectal fossa.

FIGURE 14-5. Transsphincteric fistula with supralevator extension. Drainage of the extension into the rectum is contraindicated. |

The extrasphincteric fistula involves a supralevator internal opening with a tract that passes through the entire sphincter mechanism torward its exit at the skin. It is usually a consequence of trauma (e.g., foreign body, surgical manipulation, impalement), Crohn’s disease, or pelvic inflammatory disease. It can also develop when a supralevator abscess or transsphincteric fistula with supralevator extension ruptures spontaneously into the rectum. This type of fistula represents approximately 2% to 3% of fistulas, but if the physician’s practice encompasses many individuals with inflammatory bowel disease, the incidence could be higher.

▶ PRACTICE PARAMETERS FOR TREATMENT

As has been mentioned in prior chapters, practice parameters for the treatment of a number of colorectal conditions have been established by the Standards Practice Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. These recommendations have also been established for the evaluation and treatment of fistula-in-ano.178 The reader is advised to review the society’s guidelines with respect to the latest revisions concerning evaluation and treatment of this condition.

▶ IDENTIFICATION OF THE FISTULA TRACT

How does the physician identify the type of fistula, the course of the tract, and the location of the internal opening? Numerous methods can be employed, the basic principles and procedures of which include the application of Goodsall’s rule,67 careful physical examination, probing of the tract, and a variety of injection and radiologic techniques.

Goodsall’s Rule

When the external opening lies anterior to the transverse plane, the internal opening tends to be located radially. Conversely, when the external opening lies posterior to the plane, the internal opening is usually (but not always) located in the posterior midline (Figure 14-6). One must remember that this is a “rule,” not a “law.” There are exceptions to “rules.”

There is some controversy over the reasons for the disparate manifestations. However, the reason for this eventuality probably lies with the fact that the posterior course is the result of a defect in fusion of the longitudinal muscle and the external sphincter in the posterior midline. A transsphincteric fistula is, therefore, more likely to occur in this position; the tract can then dissect into one or both ischiorectal fossae.

Cirocco and Reilly analyzed the predictive accuracy of this rule by reviewing 216 patients who underwent fistula surgery.41 Only 49% of those who harbored an external opening anterior to the transverse plane had radially directed fistulas, but the accuracy rate of Goodsall’s rule regarding posterior secondary openings was much greater.

Essentially, the rule should merely be used as a guide to help the surgeon find the tract when it may not be apparent. It is not a substitute for meticulous technique, clear identification of the direction of the tract, and location of the internal opening.

Usually, there is only one external or secondary opening. Most commonly, fistulas pass in the intersphincteric plane, but with transsphincteric fistulas, multiple openings can develop from communication with the deep postanal space and from the ischiorectal fossae; this is the origin of the so-called transsphincteric horseshoe fistula (see later).

DAVID HENRY GOODSALL (1843-1906)

|

Goodsall was born in Gravesend, England. His father had decided on medicine as a career. While performing a postmortem examination as a student at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, the elder Goodsall injured his hand and subsequently died, presumably because of sepsis. In 1865, the young Goodsall entered that same institution, his fees having been waived because of his father’s tragic death. In 1870, he was appointed house surgeon to St. Mark’s Hospital, and he became full surgeon in 1888. It was there that he developed his lifelong interest in rectal surgery. He contributed many articles to the surgical literature, including reports on foreign bodies of the rectum, pilonidal sinus, colostomy, and anal fissure. However, his best-remembered work was accomplished in concert with W. Ernest Miles, a book entitled Diseases of the Anus and Rectum. In Goodsall’s chapter on anal fistula, the rule is espoused that has become eponymously associated with Goodsall. He is thought to have died of a myocardial infarction. (Goodsall DH. Anorectal fistula. In: Goodsall DH, Miles WE, eds. Diseases of the Anus and Rectum. London, United Kingdom: Longmans, Green & Co; 1900:92.)

Physical Examination and Endoscopy

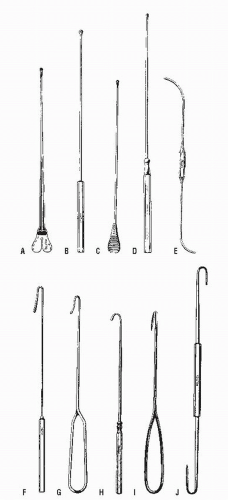

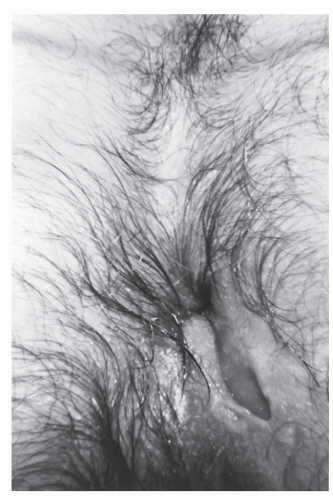

Careful palpation may reveal the thickened tract proceeding into the anal canal if the fistula assumes a relatively superficial position. This finding is most characteristic of an intersphincteric fistula. Bidigital examination, placing the thumb on the outside and the index finger within the anal canal, may also help to reveal the course of the tract. Failure to identify the tract by palpation implies that it is deep and, therefore, more likely to be a transsphincteric fistula. Anoscopic examination may demonstrate an internal opening or purulent material exuding from the base of the crypt. By gentle probing with a crypt hook or malleable probe (Figure 14-7), the presence of the tract may be confirmed. This maneuver is easier to accomplish for a radially located fistula than for one that opens in the posterior midline. Occasionally, the tract will pass subcutaneously for a considerable distance and end in the perineum, scrotum, labia, or thigh (Figure 14-8). Failure to identify the internal opening does not mean that it has closed, however. Angulation or narrowing of the tract may preclude the possibility of adequate evaluation by probing, and excessive manipulation will certainly lead to considerable discomfort for the patient. Under these circumstances, examination under an anesthetic may be required to adequately delineate the course of the tract unless one wishes to perform special studies.

At the time of bidigital examination, baseline sphincter tone, bulk, and squeeze should be assessed because this may affect the risk of incontinence with a surgical procedure.

Passing a Probe

As implied, passage of a probe can be attempted from both the external and the internal openings. Sometimes it is easier to identify the tract from the internal opening, but probing through the external one will usually reveal the course more readily. Simultaneous passage of two probes, from the internal and the external openings, may confirm the tract’s location if the tips of the probes touch. A stenotic or sharply angulated area within the tract may preclude complete passage from either end. The probe should never be forced, merely gently maneuvered in order to avoid creating another tract or sinus (Figure 14-9).

Traction on the Tract

Theoretically, if the physician mobilizes a small portion of the tract from the secondary (i.e., external) opening and

applies traction, an indentation or dimpling will be evident at the level of the crypt—the site of the internal opening (Figure 14-10). With the exception of the most simple, radially directed tracts, we have not found this particular maneuver to be helpful especially when the tract is friable and with little substance to pull on. The variable and often curvilinear course of more complex fistulas lessens the potential benefit of this method for tract identification.

applies traction, an indentation or dimpling will be evident at the level of the crypt—the site of the internal opening (Figure 14-10). With the exception of the most simple, radially directed tracts, we have not found this particular maneuver to be helpful especially when the tract is friable and with little substance to pull on. The variable and often curvilinear course of more complex fistulas lessens the potential benefit of this method for tract identification.

Injection Techniques

Dye

A DeBakey olive-end needle may be used to inject material through the opening and into the tract while an anoscope is in position in the rectum (Figure 14-11). We like to cut a 20-gauge angiocatheter at an angle to facilitate cannulation of the fistula tract. If a substance such as methylene blue or indigo carmine is injected through the tract, the dye may appear in the rectum, confirming the patency of the tract and its communication with an internal opening. The problem with such agents is that the surgeon may have only one opportunity to visualize the internal opening before the material stains the mucosa and the whole anal canal. It has been said that it would be as sensible to pour ink on a newspaper in order to facilitate reading.51 If the surgeon has no other available agent except dye, I suggest diluting it down to one part per 20.

Milk

Milk can also be used to identify the tract and the internal opening; sterility is not required. The milk can be wiped away without staining the tissue, permitting repeated attempts to inspect the internal opening. Failure to demonstrate communication with the internal opening implies stenosis of the tract, but if the milk is seen in the submucosa of the anal canal, even without escaping into the lumen, the associated crypt-bearing area should be excised with the presumption that the internal opening has closed.

Hydrogen Peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide injection is an ideal means for identifying the internal opening. The liberated oxygen may be seen to bubble through the internal opening. The pressure created by the gas may be sufficient to penetrate even a stenotic tract and pass into the anal canal. Additionally, staining of the tissue does not occur.

Imaging

Fistulography

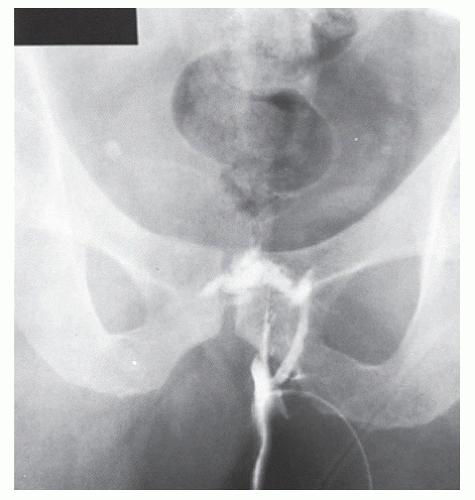

Fistulography, the radiologic delineation of a fistula tract with a water-soluble contrast agent, is thought generally to be of limited value, having essentially been completely replaced by endoluminal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).181 However, the technique is quite simple to perform. The patient is placed on the x-ray table, usually in the left lateral position, and a small-bore catheter is inserted into the external opening. A few milliliters of water-soluble contrast material are injected, and films are taken in several projections (Figures 14-12 and 14-13).

This technique does not directly image the sphincters. Thus, the relationship between the fistula and sphincter muscle cannot be determined with certainty. Additionally, the specific location of the internal opening within the anal canal is often impossible to determine. Furthermore, extensions from the primary tract may not fill, and, therefore, will not be visualized.72

FIGURE 14-12. Fistulogram with water-soluble contrast material demonstrates the course of a transsphincteric fistula with an internal opening at the level of the anorectal ring. |

FIGURE 14-13. Fistulogram of an extrasphincteric fistula. The tract enters the rectum at the level of the arrow. |

Several small studies have come to conflicting results about the usefulness of this technique. In one retrospective review of fistulography compared with subsequent surgical findings in 25 cases, fistulograms were accurate in only 16%, and false-positive results were identified in 10%.100 However, another retrospective review of 27 patients who underwent anal fistulography noted that 48% harbored unexpected pathologic features that led to an alternative surgical treatment.9 One prospective study involving 50 patients came to the conclusion that fistulography provided “helpful information.”197

The limitations of fistulography have led most specialists in colon and rectal surgery to abandon it because more precise imaging modalities are now available.

Endoanal Ultrasound

Endoanal ultrasound (EUS) may be used to image the anal canal and surrounding pelvic structures. The technique is simple to perform, although it is operator-dependant. It is noninvasive, inexpensive, and generally well tolerated. Most studies examining the accuracy of endoanal ultrasound report excellent correlation with surgical findings, particularly in visualizing the primary tract.36,46,105,187 One report noted that the surgical procedure was influenced by ultrasonographic findings in up to 38% of cases.110 In one study that compared digital examination with ultrasound, the two were equally able to identify intersphincteric and transsphincteric tracts, but ultrasound was unable to assess superficial, suprasphincteric, extrasphincteric, and supralevator or infralevator tracts. Digital examination was, therefore, considered more reliable.36

The inability to identify all extensions of complex fistulas or even primary tracts when they are beyond the reach of the instrument is a limitation of this technique. Furthermore,

scar or inflammatory tissue and the presence of abscess may limit the ability to distinguish the anatomic structures that otherwise are usually seen on endoanal ultrasound. Abscess, in particular, can appear similar to adipose tissue seen in the ischiorectal fossa. It has also typically been difficult to identify the internal opening of a fistula in the mucosa. To aid in the identification of the internal opening, the following criteria have been suggested by Cho35:

scar or inflammatory tissue and the presence of abscess may limit the ability to distinguish the anatomic structures that otherwise are usually seen on endoanal ultrasound. Abscess, in particular, can appear similar to adipose tissue seen in the ischiorectal fossa. It has also typically been difficult to identify the internal opening of a fistula in the mucosa. To aid in the identification of the internal opening, the following criteria have been suggested by Cho35:

Criterion I. Rootlike budding formed by the intersphincteric tract, which contacts the internal sphincter.

Criterion II. Rootlike budding within the internal sphincter defect.

Criterion III. Subepithelial breach connecting to the intersphincteric tract through an internal sphincter defect. Using these criteria, the internal opening may be identified in approximately 76% of cases.

However, it is unclear how many were able to be identified based on physical examination alone.

The addition of hydrogen peroxide appears to improve the accuracy of endoanal ultrasound, particularly for identifying the internal opening and secondary extensions of the fistula tract (Figure 14-14).106,144,148 The hydrogen peroxide forms hyperechoic gas bubbles that can enhance visualization of the tract (Figure 14-15). This has been particularly helpful for recurrent or complex disease in some studies, but other authors note that the improved imaging does not necessarily translate to changes in management.27 Threedimensional ultrasound has also been suggested to improve the accuracy of endoanal ultrasound. It can be used to create reconstructed images of the coronal and sagittal planes; this can be helpful in clarifying the relationship of the fistula to surrounding structures. The two techniques have been combined, but some have reported no additional benefit over three-dimensional imaging alone.95,99 Postprocessing, volume-rendered imaging has also been suggested for the enhancement of the image created by traditional ultrasound. This approach may improve contrast between structures so that primary tracts can be classified more accurately and potentially detect an abscess. However, it has not been found to affect treatment planning.20

Endoanal ultrasound may be particularly helpful in the evaluation of Crohn’s fistulas. Accuracy has been reported to be up to 91%.134,162 When a patient is treated with infliximab,

the superficial opening of the fistula may appear to have healed. However, a persistent fistula may be demonstrated on ultrasound.11 Anal ultrasound is typically not used for the characterization of straightforward fistulas. It may, however, be helpful in specific situations, such as the inability to demonstrate an internal opening, recurrent or persistent fistula following surgery, Crohn’s disease, or complicated cases.

the superficial opening of the fistula may appear to have healed. However, a persistent fistula may be demonstrated on ultrasound.11 Anal ultrasound is typically not used for the characterization of straightforward fistulas. It may, however, be helpful in specific situations, such as the inability to demonstrate an internal opening, recurrent or persistent fistula following surgery, Crohn’s disease, or complicated cases.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI produces detailed images of the perianal region and of fistula tracts via magnetic fields and radiofrequency energy. A variety of sequences and techniques, some using endoluminal anal coils, have been used. It is useful for demonstrating the relationship between the sphincters, soft tissues, and fistulas in all planes. An advantage over that of EUS is the ability to image the entire pelvic region and to, at least theoretically, see all extensions of a fistula. MRI appears to have the greatest concordance with clinical and surgical findings when compared with EUS or CT, with reported accuracy rates of 85% or greater.28,84,113 In one study, when discordance was noted between tracts on MRI not identified during surgery, there was a 52% recurrence rate following surgery.127 Subsequent findings confirmed the MRI in all cases. In contrast, the failure rate was 13% when there was concordance between surgical and MRI findings. However, in this study, surgeons acted on the MRI in 21% of cases, which biased the results. The same authors note in another small series that even though MRI can alter plan of surgery, in many instances the disagreement between imaging and examination findings did not affect the treatment plan because the classification differences were not clinically significant.30

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI has been compared with physical examination and surgical exploration.16 It appears to have a high sensitivity and specificity and is able to identify more secondary tracts. Moreover, it is felt to be more accurate in identifying complex fistulas than either digital rectal examination alone or surgical exploration.

Because of the ability to visualize extensions or areas of abscess in the pelvis not accessible by physical examination, one small study suggested that MRI may be superior to EUS at predicting outcomes of surgery.177 Spencer and colleagues reported positive and negative predictive values of 73% and 87%, respectively, for MRI and 57% and 56% for EUS.177 Others have noted that MRI may provide helpful additional information beyond what is found at EUS. In one study, MRI was particularly useful in Crohn’s disease and in classifying recurrent fistulas, thus providing helpful additional information in 40% and 24% of these situations, respectively.17 However, in two studies evaluating the use of EUS and MRI for Crohn’s fistulas, EUS was superior.162 Importantly, when any two methods were combined in one of the studies, the accuracy was reportedly to be 100%.134 This suggests that a multimodality approach may be beneficial. As with EUS, MRI can be used to evaluate the response of Crohn’s fistulas to infliximab, often showing the persistence of a fistula in the presence of superficial healing.

It is important that an MRI used to delineate fistula anatomy be read by a radiologist with experience in pelvic anatomy because there is a learning curve associated with its interpretation.161 The cost and accessibility of the machine must also be taken into account, as should medical contraindications, such as pacemakers or the inability of the patient to tolerate the contrast material. In all studies comparing imaging to either physical examination or surgical findings, the “true” or correct classification of the fistula is not known with certainty. In difficult cases, it may be impossible to truly delineate the course of the fistula. Therefore, critical review of such reports is required.

Additional Gastrointestinal Studies

Gastrointestinal evaluation, in addition to rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy, is generally unnecessary for patients with conventional anal fistula. However, in the presence of known or suspected inflammatory bowel disease, colonoscopic examination and a small bowel series are strongly encouraged.

▶ PRINCIPLES OF SURGICAL TREATMENT

Although the history of the treatment of anal fistula by means of a seton can be traced to ancient Greece (see earlier discussion), al-Zahrawi (Albucasis) is recognized as the first to use cauterization for this condition (10th century). The

management of anal fistula by division or “laying open” the tract was initially described by John of Arderne in the 14th century.10 With minor variations, this is the same method that is most commonly employed today. Percivall Pott suggested that there are essentially three means for cure: caustic, ligature, and incision.

management of anal fistula by division or “laying open” the tract was initially described by John of Arderne in the 14th century.10 With minor variations, this is the same method that is most commonly employed today. Percivall Pott suggested that there are essentially three means for cure: caustic, ligature, and incision.

ABUL QASIM KHALAF IBN AL-ABBAS AL-ZAHRAWI, ALSO KNOWN AS AL-ZAHRAWI OR ALBUCASIS (936-1013)

Al-Zahrawi was born in El-Zahra, northwest of Córdoba, Spain. He is known as one of the fathers of modern surgery for his contributions to advancing the field. He dedicated his life to medical ethics and to encouraging the knowledge of anatomy. He had great respect for the surgical theories and the works of the Greeks but introduced new surgical techniques and instruments. He is most famously known for his publication, the Al-Tasrif, a comprehensive and illustrated textbook of surgery. This monumental text is composed of 30 volumes, the last part of which deals with surgery, which in itself is divided into three books. The first deals with cauterization; the second discusses general surgery, trauma, obstetrics, gynecology, and urology; and the last covers orthopedics. He was the first to describe the use of cauterization in the treatment of anal fistula and hemorrhoids but recommended it only if the surgeon could avoid damage to the sphincter. Alternatively, he recommended the initial use of a cutting seton, which he describes in detail to treat anal fistulas. He has also been credited for performing the first thyroidectomy, being among the initial proponents of the use of anesthesia, using absorbable catgut sutures, ligation to control bleeding, and much more. The Al-Tasrif has illustrations of 200 surgical instruments, many of which are still in use today. He died in Córdoba in 1013 but his books continued to be used as resources for centuries in Europe. (Courtesy of Hussna Wakily, MD.)

|

The surgeon who initially treats the patient has the best opportunity to identify the tract, find the internal opening, and effect a cure. When this is not accomplished in the first instance, further surgery may be more complex, and the patient will be subjected to an increased risk of complications.

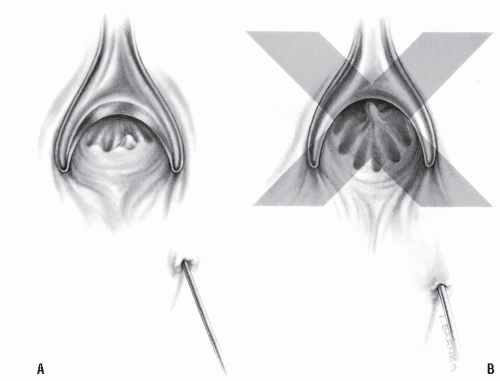

Failure to cure the patient is usually the result of either timorousness or temerity. If the surgeon traces the tract from the external opening to the level of the crypt but cannot pass the probe into the anal canal and subsequently desists from excising the crypt-bearing area, one is being too timid. In this situation, it is reasonable to assume that the crypt opening has sealed and that it is, indeed, the source of the fistula (Figure 14-16A). Likewise, if the surgeon identifies the internal opening of a “virgin fistula” but is reluctant to lay it open because of fear that the opening is too high, that decision may jeopardize the opportunity of curing the patient. The fistula will inevitably persist, and the subsequent procedure will be performed without the security of knowing that the observed internal opening occurred as a natural consequence. With few exceptions (e.g., Crohn’s disease, a history of trauma), the surgeon should be able to open the tract at the time of the initial operation without fear of causing significant impairment for bowel control. If there is concern about the safety of dividing at the level of the internal opening, a seton can be temporarily employed (see later).

Conversely, if the tract is identified only partially (i.e., not to the level of the crypt), and the surgeon elects to guess or to assume where the opening should be, thereby creating an “artificial” internal opening, one is being too aggressive (Figure 14-16B). The actual opening and the tract have not been appreciated. When the surgeon is subsequently confronted with a persistent fistula after such an ill-conceived maneuver, both the natural and the artificial internal openings must be considered.

The previously mentioned injection techniques may confirm the presence of the fistula and the internal opening. They do not, however, identify the course of the tract. If a probe can be passed, it is only necessary to incise down onto it.

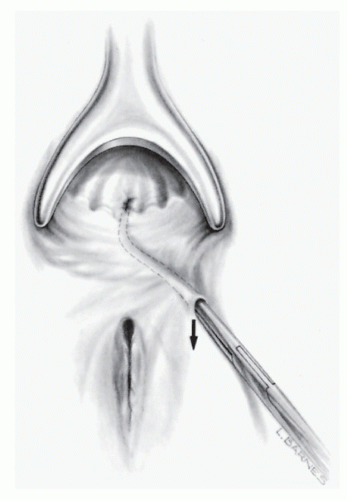

However, if this cannot be accomplished and should a fistulotomy be elected, the dissection must be carried out slowly and meticulously, following the epithelialized tract until it communicates with the anal canal (Figure 14-17).

However, if this cannot be accomplished and should a fistulotomy be elected, the dissection must be carried out slowly and meticulously, following the epithelialized tract until it communicates with the anal canal (Figure 14-17).

JOHN ARDERNE (1307-1380?)

Arderne, or de Arderne, claimed descent from Saxon times. His family was one of the first to assume a surname in imitation of the Normans. He stated that he was 70 in the first year of the reign of Richard II (i.e., 1377), hence our ability to deduce the year of his birth. He was a surgeon of the pre-Renaissance period and quite well educated, but little is known about him except for information that was gleaned from autobiographic details in some of his manuscripts. Scholars surmise that he was educated at Montpellier and served on the English side in France during the early period of the One Hundred Years War. He treated patients in Newark, Nottinghamshire, from 1349 to 1370 and then came to London. In 1376, Arderne issued his Treatise on Fistula-in-ano. A prolific writer in colloquial Latin, it was soon translated into English. Although he was apparently a brilliant surgeon, he still adhered to and promulgated astrology, keeping his medicaments and plasters secret. In fact, his fame as a pharmacist was said to have long outlasted his reputation as a surgeon. (Arderne J. Treatises of Fistula-in-Ano, Hemorrhoids and Clysters. Power D, trans. London, United Kingdom: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner; 1910.)

PERCIVALL POTT (1714-1788)

|

Pott was born in London, the son of a scrivener, in a house on Threadneedle Street at which location now sits the Bank of England. With the assistance of a relation, the Bishop of Rochester, Pott was able to attend a private school in Kent. At the age of 16, he demonstrated an interest in surgery and was apprenticed to Edward Nourse, an assistant surgeon at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. It was Pott’s responsibility to prepare anatomic subjects for Nourse’s lectures. In 1736, Pott received his diploma and was admitted to the Company of Barber-Surgeons. Following dissolution of the company in 1745, Pott allied himself with the surgeons, having been appointed assistant surgeon at St. Bartholomew’s. In his Treatise on Fistula, Pott stressed the advisability of minimal dissection, that is, the performance of limited fistulotomy. In 1756, Pott was thrown from his horse and suffered a compound fracture of the ankle. Despite having been advised to undergo amputation, he successfully managed to preserve the limb. The term Pott’s fracture is still used to describe this particular injury. In 1786, the Royal College of Surgeons at Edinburgh elected Pott an honorary fellow, the first gentleman of the faculty to whom this honor was given. He served St. Bartholomew’s Hospital for one-half century, and when he died, the place in the Court of Assistants of the Surgeon’s Company was filled by his eminent pupil, John Hunter. (Pott P. The Chirurgical Works. Vols 1-3. London, United Kingdom: J Johnson; 1808; adapted from Parks AG, Gordon PH, Hardcastle JD. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg. 1976;63(1):1-12.)

A fistula operation should always be performed with electrocautery. Identification of the tract requires a dry operative field. In such a vascular area, this is the best means for maintaining hemostasis.

Fistulotomy versus Fistulectomy

Whether to perform fistulectomy or fistulotomy has been a source of controversy. Kronborg randomly allocated patients with anal fistula to either an incisional or an excisional approach.98 Times to healing were significantly shorter when the fistula was laid open in comparison with excision, but recurrence rates were comparable. Fistulotomy is preferable because of the prolonged healing time associated with excisional techniques (Figures 14-18 and 14-19). However, a small portion of the tract may be removed for pathologic examination, especially if there is a concern about the possibility of Crohn’s disease or malignancy (see later).

Office Fistulotomy

Office fistulotomy may be undertaken synchronously with drainage of an abscess if the internal opening is low or if it is an intersphincteric fistula. It may also be performed in the office as an interval procedure following abscess drainage. Local anesthesia or a field block is usually adequate for analgesia (see Chapters 8 and 11). For the majority of patients, however, definitive fistula surgery should be performed in the operating room with a general, spinal, or caudal anesthetic under optimal conditions. A local anesthetic with conscious sedation may also be used in selected individuals. With the exception of certain complex fistulas or those in whom concomitant sphincter repair is undertaken,

the operation can usually be performed on an ambulatory basis. This is also in accordance with the recommendations of the Standards Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.179 However, the most current set of recommendations does not specifically address the issue of inpatient or outpatient management.180 Their conclusions were as follows:

the operation can usually be performed on an ambulatory basis. This is also in accordance with the recommendations of the Standards Task Force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons.179 However, the most current set of recommendations does not specifically address the issue of inpatient or outpatient management.180 Their conclusions were as follows:

FIGURE 14-17. Progressive unroofing of a fistula with electrocautery, following the tract with the aid of a probe. |

FIGURE 14-18. Fistulectomy versus fistulotomy, matters of prolonged wound healing, scarring, and deformity. |

FIGURE 14-19. Anal fistulectomy may require prolonged healing time. This wound is still open 6 weeks after the operation. |

A fistula, fistula with abscess, or a fistula associated with limited anorectal pathology may be treated on an outpatient basis if, in the judgment of the operating surgeon, it is safe to do so.

Fistulas involving adjacent organs or structures (i.e., rectovaginal, rectourethral, or horseshoe) often require more extensive surgery, and inpatient postoperative care is usually needed.

Fistulas associated with extensive cellulitis or abscess or additional anorectal disease may require inpatient care, especially if intravenous antibiotics are necessary.179

▶ SURGICAL APPROACHES AND RESULTS

Treatment of Conventional Fistula

After the external and internal openings have been identified by one of the means mentioned previously, the tract is incised (Figure 14-20). Continuity of the epithelial lining confirms the completeness of the operation, and granulation tissue is removed by curettage. A portion of the tract may be excised and sent for pathologic examination. The external portion of the incision may be widened relative to the size of the opening in the anal canal because skin tends to heal more rapidly than anal mucosa. If this is not done, delayed healing within the anal canal may result. The cut edges of the anal mucosa and the underlying internal anal sphincter can be oversewn with absorbable suture for hemostasis (Figure 14-21). The wound is otherwise left open and gently packed. Petroleum jelly gauze is preferred by some surgeons because subsequent removal is less likely to induce bleeding. Others endorse the use of iodoform

gauze, Surgicel, Telfa, or simply a gauze sponge. Tight packing should be avoided because it can lead to cellulitis and abscess.

gauze, Surgicel, Telfa, or simply a gauze sponge. Tight packing should be avoided because it can lead to cellulitis and abscess.

FIGURE 14-20. Conventional fistulotomy. With the use of electrocautery, the tract is laid open between the internal and external openings. |

FIGURE 14-21. Conventional fistulotomy. The anal opening with the underlying internal sphincter is sutured for hemostasis. |

To reiterate, the principles of operative treatment are as follows:

Identify the tract.

Incise the tract.

Excise a portion for biopsy material (if considered potentially useful).

Widen the external wound.

Suture the cut edge of the anal canal.

Gently pack the wound.

The dressing is removed the evening of surgery or the next day, and sitz baths should be performed. Vigorous mechanical cleansing of the wound is encouraged with either a washcloth or a gauze pad. The use of a Water-Pic device or comparable irrigating equipment has merit in postoperative wound management. One should be as vigorous as possible, maintaining the wound in a well-debrided and clean state. An office visit is recommended 10 days later to assess healing, and usually every 1 to 2 weeks thereafter until healing is complete. Less frequent appointments may be appropriate for individuals with straightforward fistulas if the patient understands the need for and is committed to vigorous cleansing.

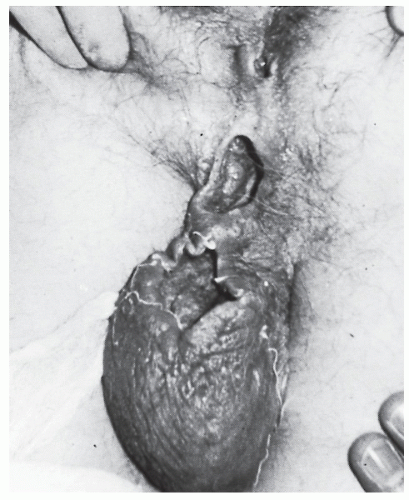

If a large portion of the external sphincter must be divided, consideration should be given to primary sphincter repair or possibly to seton division (see later discussion). An anterior fistula in a woman should always be considered for either reconstruction or another alternative to limit sphincter damage (Figure 14-22). When a fistula occurs anteriorly in a

woman, surgical treatment inevitably will create some degree of impaired control. To minimize the disability, sphincter reconstruction should be attempted at the time of fistulotomy. Another alternative for managing such a problem is to use a seton or to perform a closure of the internal opening with a sliding endorectal flap, such as that which may be recommended for rectovaginal fistula repair and high transsphincteric anal fistulas.

woman, surgical treatment inevitably will create some degree of impaired control. To minimize the disability, sphincter reconstruction should be attempted at the time of fistulotomy. Another alternative for managing such a problem is to use a seton or to perform a closure of the internal opening with a sliding endorectal flap, such as that which may be recommended for rectovaginal fistula repair and high transsphincteric anal fistulas.

Results

It is difficult to interpret the results of treatment for anal fistula for a number of reasons. One attempts to analyze variables that include an individual surgeon’s personal operative preferences and technique, the type of fistula encountered, and the cause of the problem. Not only are the variables poorly defined in the numerous published papers, but also the clinical material often consists of a melange of fistula manifestations. Most important, there is a dearth of prospective, randomized trials.

The three primary criteria for determining success or failure of fistula surgery are the following:

Recurrence

Delayed healing

Incontinence

A few generalizations can be made in attempting to interpret the published results:

The more “complex” the fistula is, the higher the internal opening will be.

The more sphincter that is divided, the longer it takes to heal, the greater the likelihood of recurrence, and the higher risk of fecal soiling.

The most likely cause of recurrence is the failure to identify and adequately treat the internal opening.

As mentioned, the results of surgery for anal fistula are extremely difficult to interpret from the published articles. Virtually all of the studies are retrospective and reflect the individual author’s personal preference for management. Despite the fact that many of these series incorporate hundreds of patients, there is no consensus that can be derived. Generally, recurrence rates vary from 4% to 10%, with missed internal openings at the initial surgery accounting for the vast majority of such recurrences.159 Certainly, those individuals with high openings, posterior openings, or fistula extensions are at increased risk for developing recurrence.192 In the experience of the University of Minnesota group, factors associated with recurrence included complex type of fistula, horseshoe extension, lack of identification or lateral location of the internal fistulous opening, prior fistula surgery, and even the variable of the surgeon.63

Besides the issue of recurrence, the other major concern is incontinence. This is reported to be noted in 10% to 50%. Again, from the Minnesota group, greater than 50% complained of some degree of postoperative incontinence.63 Articles have been published concerning manometric evaluation and anorectal function following fistula surgery.18,155,157 The self-evident conclusion is that the more one divides or fails to preserve the sphincter, the lower the resting and squeeze pressures of the anal canal. Anorectal physiology and continence were assessed prospectively before and after surgery in 50 individuals with anal infection at St. Bartholomew’s and St. Mark’s Hospitals in London.114 Functional deficit occurred in 8 of 15 patients. Bokhari and Lindsey reported on 128 patients treated with sphincter division and noted higher healing rates compared with sphincter-conserving treatment, but they found major incontinence in 13% of patients who had sphincter division compared to none in those undergoing sphincter-preserving procedures.23

Parks and Stitz reviewed 158 patients treated by the senior author over a 15-year period.138 Follow-up of at least 1 year was available in 142. There were 12 instances of recurrence (9%) and 10 fistulas that remained unhealed (7%). The recurrences were noted with all types of fistulas, and all but two of the recurrent fistulas healed with reoperation. The authors also evaluated bowel control and found that 17% who had an intersphincteric fistula had difficulty with flatus control or occasional soiling. One-third of those with transsphincteric fistulas reported one complaint or the other. It is worth recognizing, however, that, depending on the definition, no patient in either group became truly incontinent.

Hidaka and coworkers performed fistula operations on 2,242 patients, almost one-half of whom underwent “sphincterpreserving surgery.”80 They concluded that failure rates were similar and low (less than 5%).

Kuypers reported an overall recurrence rate of 4%, and a 10% incidence of some control difficulty.103 Bennett noted in 114 patients that 12% had inadequate control for feces, 16% had poor flatus control, and 24% had frequent soiling of their underclothes.19 Thirty-six percent of patients complained of one or more of the foregoing problems. Adams and Kovalcik reported an overall recurrence rate of 4% in 133 individuals.3 Hill followed 476 patients for up to 20 years.81 Delayed wound healing occurred in only 7; 4 experienced recurrence, and 19 had varying degrees of control difficulties. Results of treatment of fistula-in-ano were analyzed in 260 consecutive patients by Vasilevsky and Gordon.194 Continence problems were observed in 6% and recurrence in 6.3%. Sainio and Husa reported minor defects in bowel control in 34% of their patients.156 Of interest is their opinion that the amount of divided muscle did not influence the incidence of incontinence. Toyonaga and coworkers examined factors affecting continence after fistulotomy and found low preoperative contraction pressure and multiple previous surgeries to be independently associated with postoperative incontinence.186 However, location and level of the internal opening were not associated.

A review of the experience at St. Mark’s Hospital over a 10-year period found that fistulotomy led to closure rates of 96% to 98%, depending on the height of the opening. Only two patients in their series of 180 had a recurrence. Operation-induced incontinence, mostly to flatus, was noted in 30% to 44% of cases.13 In a large study from the Netherlands, the 3-year recurrence rate after fistulotomy was 7%, and some soiling was noted in up to 40% of patients.191 There were no clear predictors of increased risk for either failure or impaired control.

Outcomes after fistula surgery were examined on a prospective, multicenter basis by Hyman and colleagues.87 In this series, 25 surgeons contributed 245 patients. The overall healing rate was 19.5% after 1 month and 63.2% at 3 months. Long-term follow-up was not yet available. However, fistulotomy had the highest healing rates compared with draining or cutting setons, anal fistula plug, fibrin glue, or advancement flap. Nearly one-third of patients required an additional procedure during the study period, and nearly one-third were being treated for recurrent fistulas. Those treated for recurrent fistulas were less likely to heal. As noted in other studies, seton drainage did not improve success rates.

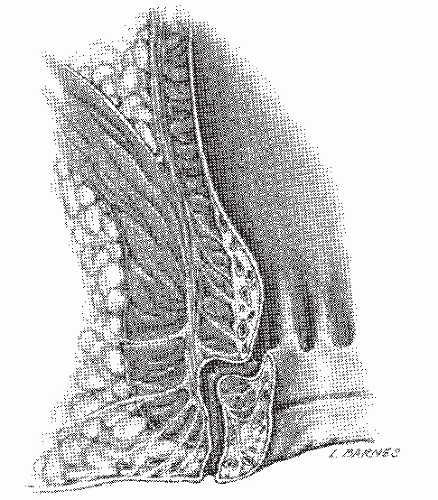

Horseshoe Fistula

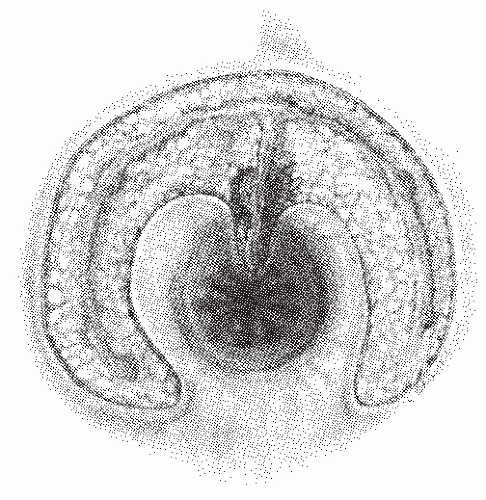

Horseshoe fistula may be intersphincteric but is much more frequently transsphincteric. It is so called because it is composed of multiple external openings joined by a subcutaneous communication in a U or horseshoe shape (Figure 14-23). The arms of the U are almost always directed anteriorly, and the internal opening is in the posterior midline. Rarely, a horseshoe fistula may present with the opposite configuration; that is, the internal opening is in the anterior midline, and the arms of the U are directed posteriorly.

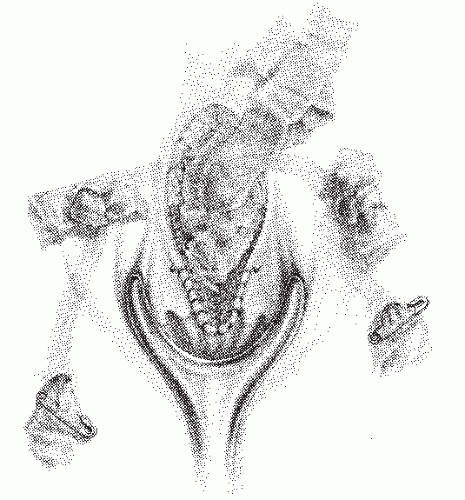

Treatment of this condition has evolved to be much less radical than originally described. The classic procedure required identification of the tracts and internal opening and unroofing or excision of each of them (Figure 14-24). This inevitably resulted in a huge, gaping wound, which required a prolonged healing time (Figure 14-25). Disability after this operation can last for many months.

In 1965, Hanley described a rather conservative approach to the management of horseshoe fistula that limits the number and extent of the incisions.75 The most important aspects of the operation are to eliminate the internal opening and to establish adequate external drainage.58,75 Because all of the tracts and external openings communicate, if the internal opening has been removed, the external openings will close. Most surgeons have successfully adopted this approach to the treatment of horseshoe anal fistula.

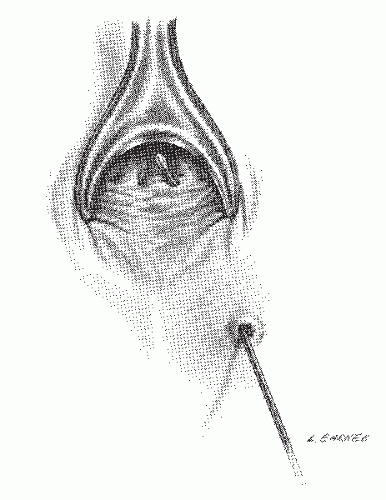

If the fistula is transsphincteric, the deep postanal space must be entered, curetted, and irrigated (Figure 14-26). This involves incision of both the internal sphincter and a portion of the external sphincter. It is then necessary only to unroof the external openings, curette the tracts, and drain the wounds (Figure 14-27). The cut edges of the anal canal and underlying internal sphincter are sutured for hemostasis. The deep postanal space is packed loosely, usually with iodoform gauze, and a dressing is applied.

FIGURE 14-23. Representation of a horseshoe anal fistula. The internal opening is in the posterior midline. |

When the fistula is approached in this way, healing is generally rapid, and the risk of functional impairment to the anus from scarring and deformity is decreased. Duration of disability is also markedly reduced.

Postoperatively, the packing is removed in 24 to 48 hours, and the patient may begin sitz baths. Weekly office visits are recommended until the wounds have healed.

Results

Hanley and colleagues reported their results in 41 patients with horseshoe fistula.76 There was no problem with healing, recurrence, or incontinence using the technique previously described. Hamilton, using the same approach, reported

four recurrences in 57 patients.74 Held and coworkers noted a recurrence rate of 18% and advised more frequent use of a seton to promote drainage and to avoid premature closure.77 Others have adopted a similar philosophy and used seton division with drainage in the management of this condition.188 In 11 patients so treated, 2 developed recurrences (18.1%). Pezim also emphasized the importance of unroofing the deep postanal space and achieved healing in 92% of his 24 patients.142

four recurrences in 57 patients.74 Held and coworkers noted a recurrence rate of 18% and advised more frequent use of a seton to promote drainage and to avoid premature closure.77 Others have adopted a similar philosophy and used seton division with drainage in the management of this condition.188 In 11 patients so treated, 2 developed recurrences (18.1%). Pezim also emphasized the importance of unroofing the deep postanal space and achieved healing in 92% of his 24 patients.142

FIGURE 14-25. Treatment of an anterior horseshoe fistula by the classic technique leaves a large, gaping wound that requires prolonged healing time. |

FIGURE 14-26. Successful management of a typical posterior horseshoe fistula requires entrance to the deep postanal space even though a portion of the internal and external sphincter must be divided. |

Treatment of Suprasphincteric Fistula

The management of suprasphincteric fistula is comparable to that of other complex fistulas. Options include endorectal advancement flap, primary closure and drainage, and seton division. In general, once the fistula has been recognized as such, fistulotomy can be accomplished distal to the internal opening by dividing the lower portion of the internal and external sphincters (Figure 14-28). The cephalad component, including the internal opening, is treated by means of seton division (see later). It is important to assess the length of the canal because men tend to have longer anal canals, whereas women tend to have shorter. Sufficient muscle must remain to preserve continence.

PATRICK H. HANLEY (1909-1994)

Patrick Hanley was born February 2, 1909, in Lockport, Louisiana. He graduated from Southwestern Louisiana Institute in 1929 and received his medical degree from Tulane University School of Medicine in 1933. He completed his surgical residency at Charity Hospital in New Orleans under the guidance of Alton Ochsner. During World War II, he served as a lieutenant commander in Bahia, Brazil, where he devoted himself to communicable disease prevention and to health education. After the war, he returned to New Orleans and to the Ochsner Clinic, at which institution he developed a training program in colon and rectal surgery. He ultimately was promoted to professor of surgery at Tulane. Hanley supervised the training of 40 fellows in colon and rectal surgery. He wrote extensively and was especially recognized for his video presentations at national meetings in which he illustrated his surgical techniques. He was considered a pioneer in the use of this modality as a teaching tool. His major contributions included investigation of perineal and perianal anatomy and the relationship of anatomic structures to fistula disease. He was elected president of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and of the International Society of University Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Patrick Hanley died on March 27, 1994. (With appreciation to David E. Beck, MD, chairman, Department of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Ochsner Clinic Foundation, New Orleans, LA.)

Treatment of Extrasphincteric Fistula

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree