Rectal Prolapse (Internal and External), Solitary Rectal Ulcer, Descending Perineum Syndrome, and Rectocele

Ian Lindsey

R. John Nicholls

Man should always strive to have his intestines relaxed all the days of his life and that bowel function should approximate diarrhea. This is a fundamental principle in medicine that whenever the stool is withheld or is extruded with difficulty, grave illnesses result.

—MOSES BEN MAIMON (MAIMONIDES): Mishneh Torah, Hilchoth De’oth, 4.13

▶EXTERNAL RECTAL PROLAPSE

Rectal prolapse (procidentia) or “falling down of the hindgut” has long fascinated surgeons. It was recognized in antiquity, having been described in the Ebers Papyrus of 1500 BC.188 It usually occurs in persons at the extremes of life. The two types of presentations are a complete or full-thickness involvement of the bowel and a partial or incomplete type involving prolapse of the mucosa only. The latter may be circumferential or may be limited to only a portion of the rectal mucosa.

Anatomy and Physiology

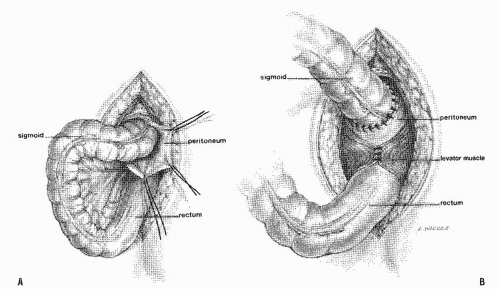

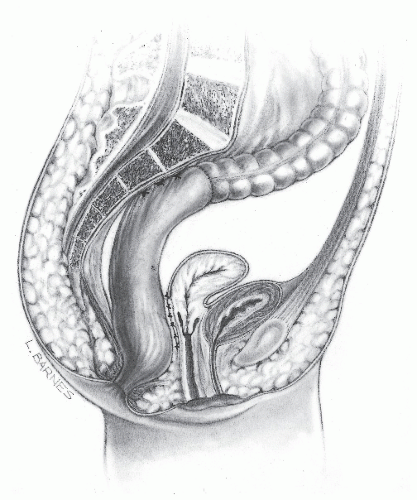

The precise cause of rectal prolapse is not fully understood, but certain factors seem to be implicated in its development.314 The normal spine with its curvature and the tilt of the pelvis serve to shift the weight of the abdominal organs forward, away from the pelvic floor and cause the rectum to follow a serpentine course through the pelvis.234 The stability of the rectum is greatly aided by the support of the levator ani muscle. An extensive interweaving of the longitudinal fibers of the rectum with the levator fibers creates a stable attachment between the rectum and this muscle. This provides a firm fixation to the pelvic floor and is an important element in rectal stability; without it, the rectum would slip down through the muscle during defecation (Figure 21-1).39,234,235 and 236

The puborectalis sling forms the functional anorectal junction and tilts it forward toward the pubis creating an acute angle, which is important for fecal continence. Relaxation results in descent of the pelvic floor, widening the anorectal angle so that the rectum and anal canal comes to lie more in a direct line.

During defecation, intra-abdominal pressure is increased by contraction of the abdominal wall musculature and the diaphragm. Contraction of the levator ani muscle is inhibited, the puborectalis sling lengthens, and the pelvic floor descends, thereby obliterating the anorectal angle. The external sphincter muscle, which functionally forms a single unit with the puborectalis sling, relaxes at the same time. The rectum now occupies a vertical position, and the fecal mass is expelled by the contraction of the circular muscle of the rectum combined with the pressure from above (see also Chapters 2 and 16 for the discussions on defecation). The rectum is held in place by fixation of the levator muscle anteriorly and by the various ligamentous structures laterally when the rectum is in a vertical position. The levator sling returns to its usual support position after defecation.

Etiology

The etiologic factors believed to produce rectal prolapse may be congenital or acquired.

Predisposing and Associated Factors for the Development of Prolapse

The following list summarizes possible predisposing influences and associated conditions:

Constipation, including evacuation disorder

Neurologic disease (e.g., congenital anomaly, cauda equina lesion, spinal cord injury, senility)

Patulous anus (i.e., weak internal sphincter)

Diastasis of levator ani muscle (i.e., defect in the pelvic floor)

Female gender

Parity

Redundant rectosigmoid

Deep pouch of Douglas

Lack of fixation of rectum to sacrum

The altered pelvic anatomy can be observed at laparotomy. This usually includes a redundant rectosigmoid and a deep rectovaginal or rectovesical pouch of Douglas.206 This is associated with increased mobility of the rectum with a more extensively covered peritoneum than in the normal situation. Whether these are truly causative factors or merely frequently associated anatomic variables has been a subject of considerable debate. Similarly, it has been questioned whether the patulous anus and weak pelvic floor musculature, with diastasis of the levator ani muscle that produces a defect in the pelvic floor, is more the result of the prolapse than its cause (Figure 21-2). In the older patient, pelvic floor weakness often with associated incontinence is the usual finding, suggesting that reduced support of the pelvic organs may be an initiating factor. There is, however, evidence of improvement of resting anal pressure after rectopexy, thus favoring the idea that the prolapse causes secondary stretching of the sphincter.279 Probably, weakness is partially causative and partially a consequence of prolapse once established. General neurologic diseases and traumatic lesions of the cauda equina may lead to rectal prolapse. Excessive pressure on the pelvic floor, particularly when related to attenuated muscle, is another etiologic factor.314

Many reports have confirmed the association between prolapse and pelvic floor muscular weakness.94,116,134,136,147,236,290,295,335

Parks and colleagues suggested that because of stretch injury to pudendal and perineal nerves, loss of continence in individuals

with rectal prolapse was secondary to prolonged protrusion.238 They cite publications that demonstrate histologic abnormalities of small nerves supplying the anorectal musculature. Neill and associates reported electromyography (EMG) studies that showed reduced amplitude of action potentials in the external sphincter and puborectalis muscles in patients with fecal incontinence, but not in those with rectal prolapse without incontinence.215 These findings indicate that denervation causes pelvic floor weakness, with prolapse and incontinence in some patients; in others, however, prolapse occurs without detectable abnormality of the pelvic musculature.

with rectal prolapse was secondary to prolonged protrusion.238 They cite publications that demonstrate histologic abnormalities of small nerves supplying the anorectal musculature. Neill and associates reported electromyography (EMG) studies that showed reduced amplitude of action potentials in the external sphincter and puborectalis muscles in patients with fecal incontinence, but not in those with rectal prolapse without incontinence.215 These findings indicate that denervation causes pelvic floor weakness, with prolapse and incontinence in some patients; in others, however, prolapse occurs without detectable abnormality of the pelvic musculature.

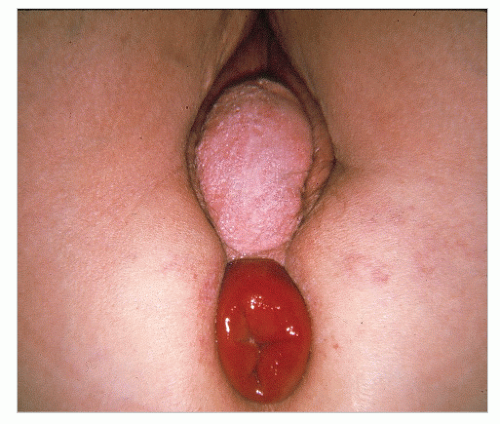

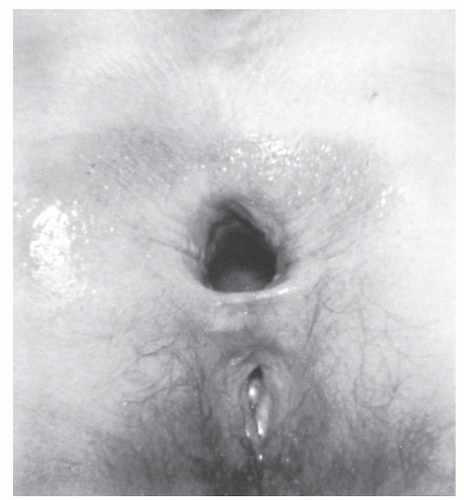

FIGURE 21-2. Patulous anus is seen after prolapse has been reduced. (From Corman ML, Veidenheimer MC, Coller JA. Managing rectal prolapse. Geriatrics. 1974;29(10):87-93, with permission.) |

In infants, prolapse may be caused by a lack of skeletal support and by excessive intra-abdominal pressure (see Rectal Prolapse in Children). In adults, prolapse may result from incomplete skeletal development. A free mesentery to the entire colon and rectum is a congenital anomaly that may undermine the support mechanism. Because of the complicated development of the levator ani muscle and its fixation to the rectum, anomalies of this muscle including tenuous fixation to the rectum may occur more often than is realized and may also contribute to instability of the rectum.

Brodén and Snellman,34 Ripstein and Lanter, and others introduced the concept of intussusception as the primary cause of rectal prolapse.65,66 and 67,258,261,305,314 What initiates the intussusception is not exactly clear, but, as demonstrated cineradiographically, over a period the intussusception draws the rectum farther from the sacrum as it descends, and eventually the bowel presents at the anal verge.34,258,305 Lack of fixation of the rectum to the sacrum can be observed both at the time of laparotomy and cineradiographically. When the act of defecation is viewed by this means or by defecography (see Defecography), the sequence of events is confirmed. A so-called colorectoanal intussusception may also occur in patients with a rectal tumor, which acts as a lead point.346

Patients in psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions are occasionally afflicted with this condition. Goligher, as a nonpsychiatrist, described one-third of his patients as being “rather odd,” with approximately 3% “definitely psychotic.”96 Nearly one-half of the Lahey Clinic (Boston) patients demonstrated somewhat aberrant behavior.139 The reason for the frequency of mental disturbance is not clearly understood.

By far, the most common group of patients with prolapse, however, are those in the sixth decade of life and older. In contrast to the younger age group, most (90%) are women.139 Multiparity has sometimes been cited as an etiologic factor, but in the Lahey Clinic experience and in that of others, 40% to 60% are nulliparous.139 Boutsis and Ellis reported that 58% of their patients with prolapse were childless, and Hughes reported an incidence of 39%.32,128 Such rates of nulliparity are much higher than would be expected in the general population.

Clinical Features

Anorectal Assessment

It is important to determine the tone and contractility of the sphincter. If the resting tone is poor and the anus is patulous, and if the patient is unable to contract the external sphincter

and puborectalis voluntarily, the functional results after repair may be suboptimal. Conversely, if the patient has relatively good sphincter tone and contractility, good bowel control can be anticipated following successful repair. It is also important to specify the degree of prolapse and whether it is full thickness or mucosal.

and puborectalis voluntarily, the functional results after repair may be suboptimal. Conversely, if the patient has relatively good sphincter tone and contractility, good bowel control can be anticipated following successful repair. It is also important to specify the degree of prolapse and whether it is full thickness or mucosal.

JOHN CEDRIC GOLIGHER (1912-1998)

|

Goligher has been described as the preeminent clinical investigative surgeon in the world. He was born in Londonderry, Northern Ireland. He achieved his medical degree in 1934 from the University of Edinburgh, and after serving as a house officer at the Royal Infirmary in that city, he took the post of resident surgical officer at St. Mark’s Hospital in London. Following a period as senior registrar at St. Mary’s Hospital, he accepted a position as consultant surgeon to both St. Mary’s and St. Mark’s in 1947. In 1955, he assumed the chair of the University of Leeds, Department of Surgery, and at the General Infirmary, achieving emeritus status in 1978. Professor Goligher’s papers represent a spectrum of accomplishment that is unparalleled in contemporary surgery. His individually authored text, Surgery of the Anus, Rectum and Colon, flourished through five editions. Others may continue to attempt to imitate his mastery of the field, but none can equal it. He has been responsible for more than 15 named lectures and has been recognized through honorary fellowship in as many societies throughout the world, including that of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. His theatres in Leeds had been the center for every surgeon pursuing an interest in gastrointestinal disease. Professor Goligher was indeed the personification of the master surgeon.

A thorough endoscopic examination is necessary in individuals with any anorectal complaint, and this is especially true for patients with rectal prolapse. Occasionally, a polyp or carcinoma of the rectum or sigmoid colon may be the “lead point” for an intussusception. A high index of suspicion should be maintained, especially in a male patient with no evidence of neurologic disease. Total colonic evaluation by colonoscopy is mandatory. Flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy should exclude a tumor, and it may also reveal an intussusception if performed with the patient straining.260 Evacuation proctography may be helpful if the diagnosis is in question.

Older Patients

In the older age group, the most frequent primary complaint is referable to the prolapse itself. Three-quarters of patients report a lump in the perineum. Problems with bowel regulation and incontinence are also common presenting features. At least 50% have a history of constipation.139 Major bleeding is rare unless the prolapse is massive or irreducible. The patient may, however, complain of small amounts of blood and mucous soiling the underwear.

Fecal incontinence is frequently associated with prolapse. Indeed, among the one-quarter of patients who do not report a lump, many will complain of fecal incontinence as the main presenting problem. Rectal prolapse should be suspected whenever this symptom presents, especially in the elderly.90 Incontinence becomes more severe as the protrusion increases in degree. Dilatation of the canal by the mass results in further relaxation of the sphincter muscles and further prolapse.281 Protrusion may occur when the patient lifts or coughs, not necessarily solely upon defecation. Initially, the prolapse may retract spontaneously, but manual replacement, eventually, may become necessary. Ultimately, the mass may protrude most of the time. Infrequently, the prolapse may become incarcerated or even strangulated resulting in a surgical emergency (Figure 21-3). Transanal evisceration of the small bowel through a rent in the protruding rectum has also been reported.97 Anorectal or pelvic pain is an underrecognized symptom of rectal prolapse. In one study, it was present at least some of the time in up to 50% of patients.125

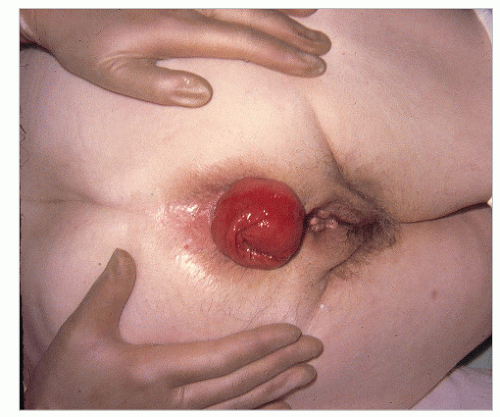

FIGURE 21-4. Standard, full-thickness rectal prolapse or procidentia. (From Corman ML, Veidenheimer MC, Coller JA. Managing rectal prolapse. Geriatrics. 1974;29(10):87-93, with permission.) |

The duration of symptoms before the patient seeks attention is often quite prolonged. This may be a reflection of the patient’s psyche, but too often it represents failure of the family physician to recognize the entity and to recommend appropriate consultation.

Diagnosis

Usually, the diagnosis of a full-thickness prolapse is obvious on inspection of the perineum (Figure 21-4), but if it is not evident, the patient should be asked to go to the bathroom and to strain as in defecation. Once seen, the diagnosis is made. Rectal prolapse may be associated with uterine descensus (Figure 21-5) or prolapse (Figure 21-6) or with a cystocele (Figure 21-7).56

Younger Patients

These patients often have a pronounced functional disturbance of defecation. This may be characterized by frequent visits to the bathroom (e.g., more than 10 times per 24 hours), with long periods spent there on each occasion. In severe cases, the patient may be spending several hours in the bathroom straining. In these individuals, the gender ratio is approximately equal. Such patients may have psychiatric symptoms, whereas others may show obsessional features.

On clinical examination, the patient is usually young and healthy. There is often a degree of perineal descent, sometimes considerable. The sphincter may be patulous as may be appreciated in the older age group, but it may be normal and sometimes it is hypertonic. The prolapse usually requires straining to demonstrate. The mucous membrane of the rectum may appear irritated, and there may be free mucus in the rectum as well as mucosal changes suggestive of the solitary ulcer syndrome.

FIGURE 21-7. Rectal prolapse with fourth-degree cystocele. (From Corman ML, Veidenheimer MC, Coller JA. Managing rectal prolapse. Geriatrics. 1974;29(10):87-93, with permission.) |

Differential Diagnosis

The condition that most often misleads the examiner into believing he or she is dealing with procidentia is prolapsed hemorrhoids (see Figure 11-8). A protruding mass of hemorrhoidal tissue tends to be lobular with a definite sulcus or groove between it and the perianal skin. With very large hemorrhoids that have become edematous and thrombosed, the enlarged size may give the incorrect impression that the entire rectal wall is protruding. However, in rectal prolapse, concentric rings of intact tissue are evident throughout the entire circumference.

The differential diagnosis includes any large rectal polypoid lesion prolapsing through the anus. The prolapsed lesion should be replaced, and the rectum should be examined manually and endoscopically. A polypoid tumor is usually mobile and can be separated from the lower part of the rectum and anal canal by digital examination. Proctosigmoidoscopic examination should clarify any differential diagnostic difficulty.

Anal deformity associated with hemorrhoidectomy, fistula surgery, and pull-through procedures may produce an ectropion or mucosal prolapse, but this should pose no difficulty in differential diagnosis. However, it is extremely important to distinguish full-thickness from mucosal prolapse because treatment of the two conditions is different. Unfortunately, some patients have undergone multiple anal operations because rectal prolapse has been mistaken for hemorrhoids.

Physiologic Studies

There is merit for performing certain physiologic studies, especially when there are symptoms of incontinence.120,166 The various studies and techniques are discussed in Chapters 7 and 16. Sun and colleagues evaluated anorectal pressures at rest, during contraction, and during balloon distension of the rectum in individuals with full-thickness rectal prolapse, anterior mucosal prolapse, and solitary rectal ulcer.302 When compared with control subjects, those with rectal prolapse, mucosal prolapse, and solitary rectal ulcer had lower anal pressures, demonstrated a higher incidence of repetitive rectal contraction, and required lower threshold volumes to stimulate a desire to defecate. The authors hypothesized that the similarity of these observations suggests that the three disease entities share a common pathophysiology. Solitary rectal ulcer is discussed elsewhere in this chapter.

Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML) studies are also discussed in prior chapters and should be considered in patients with prolapse. The demonstration of pudendal neuropathy may indicate a worse outcome of surgical repair than when this is absent. Although pudendal neuropathy is not a contraindication for repair, it is helpful to know this in advance to be able to give the patient an idea of the prognosis. Others report that fecal continence after surgical

correction of the prolapse can be predicted by postoperative measurement of the PNTML.26

correction of the prolapse can be predicted by postoperative measurement of the PNTML.26

Treatment of External Rectal Prolapse

In general, partial or incomplete (i.e., mucosal) prolapse should be treated by an anal operation. If only one quadrant is involved, simple excision, leaving the wound open, may be all that is required (see Figure 11-65). If the protruding area is circumferential, excision with an S-plasty may be considered (see Figures 11-75 and 11-79). Another suggestion for the management of mucosal prolapse is the use of the circular stapler, especially the so-called PPH modification (stapled hemorrhoidopexy; see Chapter 11).10

With respect to the management of acute, incarcerated (i.e., irreducible) rectal prolapse (Figure 21-3), some have recommended a local anesthetic to paralyze the sphincters and to effect reduction (see Figure 11-37). Others suggest a spinal or general anesthetic. The placement of ordinary table sugar or powdered sugar on the bowel mucosa can result in decreased edema and spontaneous or easily induced reduction from the desiccating effect. This is a well-recognized technique in the veterinary literature.209 Emergency resection is occasionally indicated, usually because of compromised viability.253

Nonoperative Treatment of Rectal Prolapse

If surgical treatment for incomplete or complete prolapse is contraindicated, or if the patient refuses an operation, numerous noninvasive approaches and limited office procedures may be employed as follows:

Adhesive strapping of buttocks

Manual anal support during defecation

Correction of constipation

Establishment of workable time and method of defecation

Perineal strengthening exercises

Electronic stimulation

Injection of sclerosing agent

Rubber ring ligation

Infrared coagulation

Although instructing the patient on proper bowel management and perineal exercises may be salutary, and other methods may offer some degree of palliation of symptoms, these measures cannot be expected to produce a cure.

Surgical Therapy for Rectal Prolapse

More than 50 operations have been designed for the treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Most are variations of a few basic modes of therapy and depend on the surgeon’s concept of the anatomic defect. The options for treatment include narrowing of the anal orifice, obliteration of the peritoneal pouch of Douglas, restoration of the pelvic floor, resection of the bowel (by an abdominal, perineal, or transsacral approach), and suspension or fixation of the rectum to the sacrum or to other structures. Additional operations are listed that combine one or more of these approaches.

| |

Transabdominal Perineal Transsacral | |

| |

To sacrum To pubis To other structures | |

| |

Many of the techniques described are included for historical completeness only. The vast majority of procedures these days involve either an abdominal rectopexy (usually a posterior sutured rectopexy, with or without resection, or increasingly a laparoscopic ventral rectopexy) or a perineal procedure (either Delorme’s or Altemeier’s procedure). The decision making between the two approaches has generally hinged on the balance between recurrence and safety. Higher rates of recurrence are noted following perineal procedures (15% to 20%), but this may be considered an acceptable trade-off for the safety of avoiding a laparotomy in often elderly patients with benign disease, albeit, by an operation with a lower recurrence rate (less than 5%).89,182 Undoubtedly, the advent of laparoscopy has made an abdominal approach safer, shifting the balance in favor of this approach even in the elderly (see Chapter 19).40,141,333 The recurrence rates of the laparoscopic approach are and should be comparable to that of the open technique.

Perineal Procedures

Rectopexy is generally considered preferable by some surgeons for correction of rectal prolapse, owing to the lower recurrence rates (less than 5%) than after perineal procedures (pooled series, 18%).182 This difference has, however, not been conclusively established. Recent Cochrane analyses have cited a lack of high-quality data.18 For this reason, the PROSPER study was set up in the United Kingdom to compare perineal and abdominal surgery for rectal prolapse. Its findings are yet to be published, but early reports suggest recurrence rates of 20% and 10%, respectively. Generally, perineal procedures are advised for older, frailer patients.

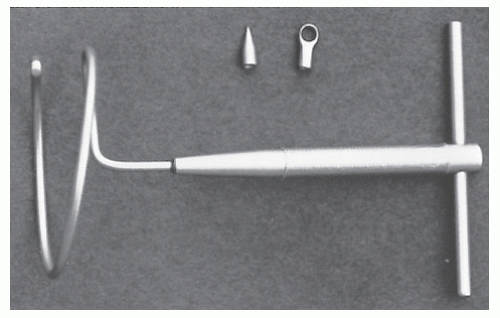

Thiersch Repair

In the older, poor-risk patient, some surgeons preferred to use the Thiersch operation but this is now only rarely performed.95,116,153 It can be carried out under local anesthetic, making it a satisfactory technique for these individuals. In the historic operation, silver wire was placed into the perianal space to encircle and narrow the anus. Today, surgeons have abandoned the use of wire because of the complications of breakage and ulceration. Other materials such as nylon, Mersilene, Dacron, polypropylene mesh (i.e., Marlex), Teflon, fascia lata, silicone rubber, Silastic, and Dacron-impregnated Silastic mesh have been used for the same purpose (Figure 21-8).84,111,126,129,153,162,177,222,244,247,268,303

Other Thiersch-Type Repairs (Historical)

Other approaches have been advocated as alternatives to the Thiersch operation. Marlex mesh has been employed by Lomas and Cooperman.177 Despite their wound infection rate of 33%, they believe this to be a rapid, safe procedure for use in the elderly patient who is not a candidate for a more extensive surgical operation.

Notaras used a ribbon of Mersilene (approximately 4 cm wide), passing it around the anus as has been described with the other material, except that a more extensive mobilization is required, and the mesh is placed more deeply.222 Notaras reported an experience with 18 patients with no

infection, breakage, or erosion.222 Sainio and colleagues reported 14 selected patients with prolapse who underwent anal encirclement with polypropylene mesh.268 Although two had recurrences (15%), no breakage, erosion, or infection was observed. Labow and associates described the use of an elastic fabric sling, a Dacron-impregnated Silastic sheet (see Figures 16-64,16-65 and 16-66).162 Hunt and colleagues treated 43 patients (mean age, 80 years) for full-thickness prolapse by implanting Silastic rods.129 The authors reported adequate control of the prolapse in 71% of patients, with no operative mortality.

infection, breakage, or erosion.222 Sainio and colleagues reported 14 selected patients with prolapse who underwent anal encirclement with polypropylene mesh.268 Although two had recurrences (15%), no breakage, erosion, or infection was observed. Labow and associates described the use of an elastic fabric sling, a Dacron-impregnated Silastic sheet (see Figures 16-64,16-65 and 16-66).162 Hunt and colleagues treated 43 patients (mean age, 80 years) for full-thickness prolapse by implanting Silastic rods.129 The authors reported adequate control of the prolapse in 71% of patients, with no operative mortality.

CARL THIERSCH (1822-1895)

|

Thiersch was born in Munich, Germany, to a very educated family. His father held the Professorship of Classics in the university and was president of the Academy of Science. Following his graduation from the gymnasium, the young Thiersch entered the study of medicine in his home university. Then, after a period at a number of European medical centers, he joined the Munich faculty. At the age of 32, he achieved professorial status. Shortly thereafter, he accepted a position as professor of surgery in Erlangen, and after 14 years, Leipzig. Like most of his contemporaries, he was expected to be a general surgeon, but his work with children and his head and neck surgery were particularly well recognized. The operation for which he was most famous was the preparation of thin skin grafts (i.e., Thiersch grafts), founded on his earlier microscopic investigations of granulation tissue. His name is also associated with the field of colon and rectal surgery for his suggestion of the management of procidentia by means of the circumanal placement of a silver wire.

Swerdlow addressed the issue of performing the operation through only one incision.303 He describes a helical rod (the Encircler)—a single loop having a diameter of 6 cm with an extension beyond 360 degrees—the end of which is adapted to accept varying tips (Figure 21-9). Khanduja and colleagues presented their experience with a compressible prosthesis composed of silicone elastomer surrounded by a silicone-coated Dacron tape.153 Dacron mesh is embedded in the ends for reinforcement. Sixteen “extremely poor-risk” individuals were submitted to the procedure. Complications included breakage of the prosthesis in three, infection in one, and late sepsis in one individual. Ladha and colleagues employed the Angelchik antireflux prosthesis—a device that was introduced for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux—for the repair of rectal prolapse in elderly patients.163 The prosthesis is placed in a supralevator location around the rectum, a position that may help to restore the anorectal angle. The authors reported eight patients, with one death and one complication of wound sepsis.

Perineal Procedures

Perineal resection of the prolapse, or rectosigmoidectomy, is an operation that has been employed for more than 100 years. Indeed, it was the routine method of surgical treatment for many years, with the advantage of being simple and safer than abdominal procedures. Unfortunately, the high rate of recurrence (up to 25%) dissuaded many surgeons from adopting this approach.128 However, this attitude has changed in recent years with improvements in surgical technique, such as that of the Altemeier’s and Delorme’s procedures. Perineal removal may be the safest approach in the rare circumstance of a strangulated, nonreducible prolapse where gangrene may occur. The functional results of perineal procedures are less predictable than with abdominal operations, particularly fecal continence.

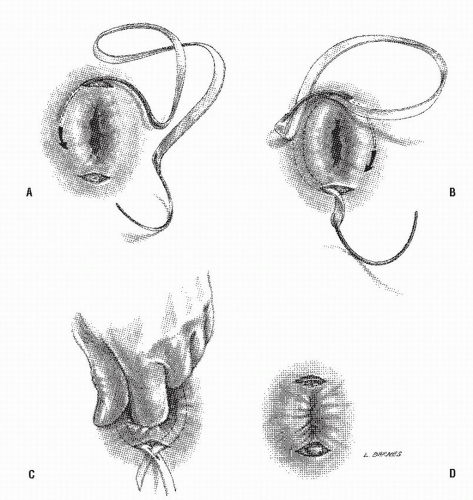

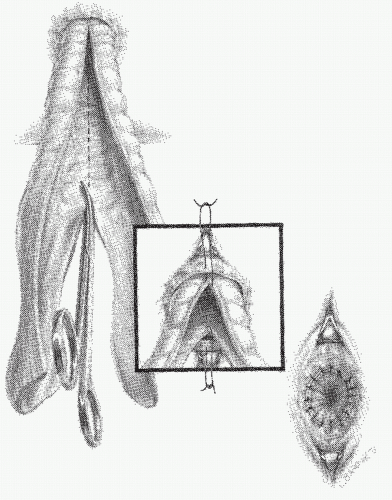

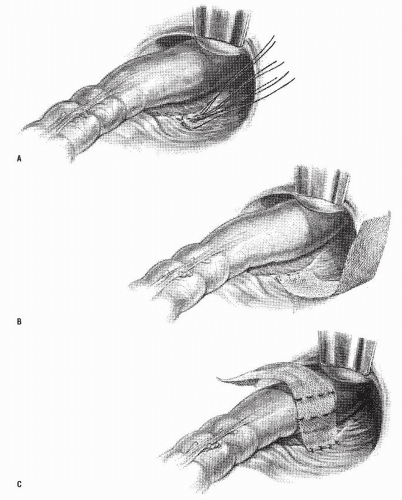

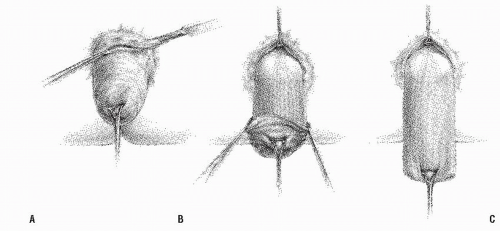

Altemeier’s Operation

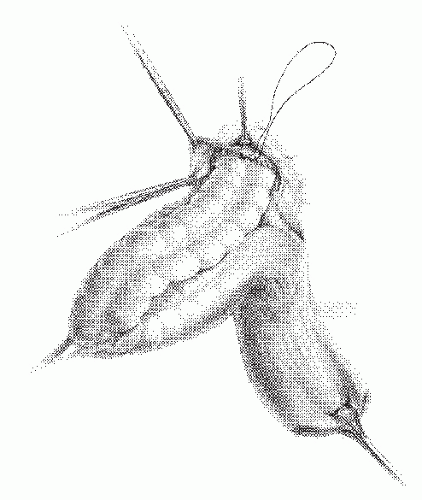

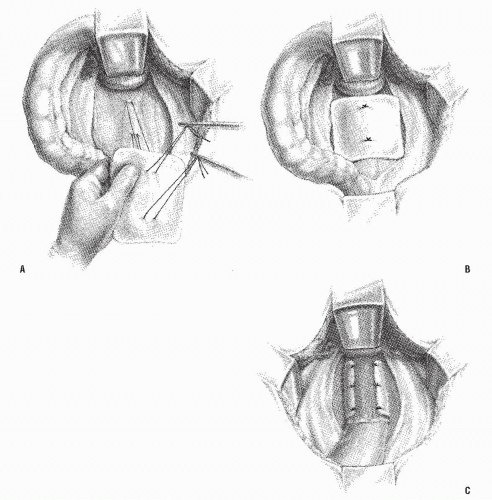

Altemeier and Culbertson developed a modification of perineal resection.6,7 They advocated the operation with the patient placed in the lithotomy stirrups. Although this is the position that is illustrated in this text, our own preference is to place the patient in the prone jackknife position on the operating table. This permits one’s assistants to be involved in the procedure and to offer the needed help. The prolapse is exteriorized, and its apex is grasped with clamps (Figure 21-10A). A circumferential incision is made through all layers of the outer bowel wall 1 cm proximal to the mucocutaneous junction (Figure 21-10A). When the circumferential incision is completed, clamps are reapplied to the distal edge of rectum (Figure 21-10B), and the prolapse is delivered as a single loop of exteriorized bowel (Figure 21-10C). With a deep pouch of Douglas, it is usually quite straightforward to enter the peritoneal cavity by incising the peritoneum anteriorly (Figure 21-11A). The redundant colon is delivered through the defect (Figure 21-11B). The peritoneum is ultimately repaired using a continuous suture to obliterate the sac, excising redundant peritoneum (if necessary), analogous to that of the technique employed for a sliding hernia (Figure 21-12).

A modification of this procedure involves plication of the levator ani muscle. This maneuver is thought by some to be associated with a lower incidence of recurrence and may have an ameliorative effect on problems with bowel control.50 The levator ani muscles are identified and plicated anterior or posterior to the bowel with interrupted long-term absorbable sutures (Figure 21-13). This eliminates the large defect in the pelvic diaphragm. The redundant intestine is then divided in half by anterior and posterior incisions carried to the point of the proposed resection (Figure 21-14). The intestine is

transected obliquely and progressively, completing the anastomosis of the intestinal wall to the distal rectum/anal ring in each quadrant (Figure 21-14). The anastomosis is fashioned with an interrupted long-term absorbable suture technique; no drains are used. Others have successfully used the circular stapler for reestablishment of continuity.21 In principle, the pelvic pouch is obliterated, the levators are plicated, and the redundant bowel is resected. The rectum is not usually fixed to the sacrum.

transected obliquely and progressively, completing the anastomosis of the intestinal wall to the distal rectum/anal ring in each quadrant (Figure 21-14). The anastomosis is fashioned with an interrupted long-term absorbable suture technique; no drains are used. Others have successfully used the circular stapler for reestablishment of continuity.21 In principle, the pelvic pouch is obliterated, the levators are plicated, and the redundant bowel is resected. The rectum is not usually fixed to the sacrum.

WILLIAM ARTHUR ALTEMEIER (1910-1983)

|

Altemeier was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the son of a railroad employee. He attended the University of Cincinnati, receiving a bachelor of science degree in 1930 and his doctorate in medicine 3 years later. After a surgical residency at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Michigan and a period as an associate surgeon, he returned to Cincinnati General Hospital as an instructor. He rose to become professor and chairman of the department of surgery in 1952, positions he retained for 26 years. Altemeier was a member of at least 38 surgical societies, serving as president of 10 of them, including the American College of Surgeons and the American Surgical Association. He developed a special interest in surgical infections and became one of the world authorities in this discipline. However, it is the management of procidentia with which his name is eponymously associated.

FIGURE 21-10. Altemeier procedure. A: An incision is made circumferentially in the anal canal, just above the dentate line. B,C: The rectum is mobilized and completely everted. |

Despite the success experienced by some authors, the complex technique and the unfamiliar approach dissuade most surgeons from attempting the operation. Altemeier and colleagues reported the results in 106 patients, of whom three developed recurrence.8 Gopal and colleagues noted only one failure with

18 elderly, debilitated individuals so treated.98 Kimmins and coworkers performed the modified Altemeier’s procedure on 63 patients (mean age, 79 years), noting an overall recurrence rate of 6.4% (median follow-up, 20.8 months).154 So benign is this operation for most patients that, in their experience, almost two-thirds were discharged the day of surgery.

18 elderly, debilitated individuals so treated.98 Kimmins and coworkers performed the modified Altemeier’s procedure on 63 patients (mean age, 79 years), noting an overall recurrence rate of 6.4% (median follow-up, 20.8 months).154 So benign is this operation for most patients that, in their experience, almost two-thirds were discharged the day of surgery.

FIGURE 21-11. Altemeier procedure. A: The peritoneal reflection is identified and opened. B: Any redundant bowel is delivered through the peritoneal defect. |

FIGURE 21-12. Altemeier procedure. The peritoneum is closed, and the sutures are anchored to the bowel wall as illustrated. |

Others have described similarly favorable results with the addition of a posterior levator plication.250 The Cleveland Clinic Florida group compared the outcomes of perineal rectosigmoidectomy with and without levatorplasty in 109 patients.50 Recurrence rates and mean time to recurrence were 20.6% and 13.3 months when rectosigmoidectomy alone was performed. When levatorplasty was added, the recurrence rate was 7.7%, and mean time to recurrence increased to 45.5 months. However, Friedman and associates considered the Altemeier’s operation unsatisfactory.92 In 27 patients, 50% experienced recurrence. When incontinence is discussed in publications, it seems that better functional results are achieved with concomitant levator plication than with proctosigmoidectomy alone.2,51,254,334 The Cleveland Clinic Florida group noted that a prolonged PNTML was not shown to be an accurate predictor of postoperative incontinence nor was there a statistically significant difference in functional outcome, both groups having marked improvement in continence scores.50,135 In the experience of the University of Minnesota group with 114 patients treated by perineal rectosigmoidectomy, a 10% incidence of recurrence was observed.334 Ramanujam and coworkers performed this operation on 72 elderly, high-risk patients, 9 of whom presented with acute, incarcerated rectal prolapse.254 Their recurrence rate was 5.5%. In another report from the same group, 8 elderly patients were treated for acute incarcerated prolapse, half of whom developed gangrene.253 There were two (25%) cases of anastomotic leakage. There were, however, no deaths. Deen and colleagues performed a randomized trial, comparing anterior resection and rectopexy with perineal rectosigmoidectomy.59 Pelvic floor repair was undertaken in both groups. There was no recurrence in 10 patients in the former group, but 1 occurred in the latter (10%). The abdominal operation was believed to be associated with better functional and physiologic results.

Vermeulen and associates reported another approach to perineal rectosigmoidectomy without levator plication by the use of the circular stapling device (Figure 21-15).326 In nine women (mean age, 79 years), they noted no significant complications and no recurrences. They believed that this technique is the procedure of choice in the elderly, poor-risk patient.

Transtar

Occasional short reports have appeared describing the use of Transtar (Ethicon Endo-Surgery) to perform a form of perineal Altemeier’s procedure (Figure 21-16). There are theoretic concerns using this technique, in particular the security of stapling the superior rectal artery within the mesorectum. Scherer reported on 15 patients who underwent this procedure.278 In 14, perineal stapled prolapse resection was performed without complications, with a median operating time of 33 minutes (range, 22 to 52). One procedure was changed to an Altemeier because of a staple line disruption. Two patients required reintervention as a result of postoperative hemorrhage. No other serious complications occurred. At follow-up, all patients were well and showed no early recurrence of prolapse.

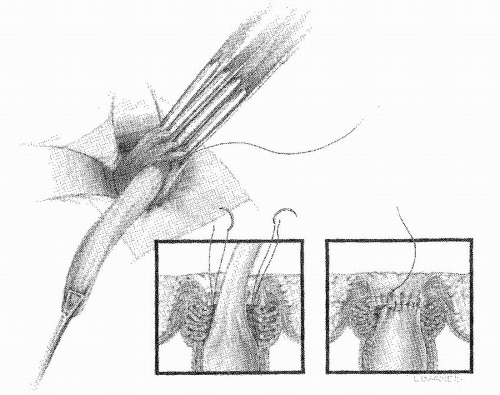

Delorme’s Procedure

Since its original description by the French military surgeon Delorme in 1900,64 this operation has reemerged in recent years as a good choice for mucosal prolapse and as an alternative to abdominal surgery for full-thickness rectal prolapse.65,283,313 The dissection may be facilitated by employing the suggestions of Sullivan and Garnjobst and Berman and colleagues.23,299 With the patient in the lithotomy or the prone jackknife position,

a circumferential incision is made 1 cm proximal to the dentate line, similar to that for the Altemeier’s procedure (Figure 21-17A). The bowel is not divided, however. This is a submucosal dissection with a mucosal stripping (Figure 21-17B). Using electrocautery, the mucosa is stripped to the apex of the protruding bowel. Dissection may be facilitated by infiltrating the submucosa with saline or a dilute epinephrine solution. Some have advocated the use of the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator for the dissection (Extracorporeal Medical Specialties, King of Prussia, PA).105 The redundant mucosa is excised, and the denuded muscularis propria is pleated longitudinally, collapsing the bowel like an accordion (Figure 21-18). The edges of the mucosa are then sutured. Alternatively, the mucosa-muscularis layers can be directly reapproximated in

a circumferential fashion with multiple interrupted absorbable sutures.105 Complications from this operation are common and include hemorrhage, hematoma, suture line dehiscence, stricture, incontinence, and, of course, recurrence.

a circumferential incision is made 1 cm proximal to the dentate line, similar to that for the Altemeier’s procedure (Figure 21-17A). The bowel is not divided, however. This is a submucosal dissection with a mucosal stripping (Figure 21-17B). Using electrocautery, the mucosa is stripped to the apex of the protruding bowel. Dissection may be facilitated by infiltrating the submucosa with saline or a dilute epinephrine solution. Some have advocated the use of the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator for the dissection (Extracorporeal Medical Specialties, King of Prussia, PA).105 The redundant mucosa is excised, and the denuded muscularis propria is pleated longitudinally, collapsing the bowel like an accordion (Figure 21-18). The edges of the mucosa are then sutured. Alternatively, the mucosa-muscularis layers can be directly reapproximated in

a circumferential fashion with multiple interrupted absorbable sutures.105 Complications from this operation are common and include hemorrhage, hematoma, suture line dehiscence, stricture, incontinence, and, of course, recurrence.

EDMOND DELORME (1847-1929)

|

Delorme was born in Lunéville, France, the son of a cabinetmaker. He demonstrated an interest in military sciences and enrolled in the medical military school at Strasbourg in 1866. He followed the army in its battles throughout Europe and North Africa, and in 1877 Delorme was named professor of operative medicine at Val-de-Grâce, and ultimately, professor of clinical surgery. He was the director of a number of hospitals and introduced the concept of antisepsis into French military medicine. In 1903, he became head of all the health services of the French Army. A highly influential surgeon, he was elected successively president of the French Academy of Medicine, the Society of Surgery, and the Society of Military Medicine. He also held the title of grand officer of the Legion of Honor. His contributions to surgery were in the treatment of war injuries, fractures, lung decortication, and rectal surgery. In his publication of the operation for rectal prolapse that bears his name, Delorme reported three patients, one of whom died.

In 30 patients treated by Nay and Blair, a 10% incidence of incontinence or recurrence was noted.214 Uhlig and Sullivan have been quite enthusiastic about this technique, reporting only three failures in 44 patients, an incidence of less than 7%.321 McCaffrey recommended this approach after a failed abdominal suspension operation.193 He reported good results in 3 patients. Gundersen and colleagues noted “significant complications” in 17% of 18 patients so treated.105

The St. Mark’s Hospital experience was published in 1994.283 Only 32 operations were performed between 1978 and 1990. There was no mortality and one anastomotic dehiscence. With a mean follow-up of 24 months, there were four recurrences (12.5%). Approximately one-half noted improved bowel control. The operation was recommended on so-called unfit patients. Oliver and associates analyzed their experience of 41 individuals who underwent this procedure.226 This operation was selected when advanced age and/or poor health contraindicated an abdominal operation. The mean age was 82 years. They noted a 22% recurrence rate. One patient died, and minor complications were seen in 25%. The authors observed the importance of an adequate mucosectomy.226 Others suggest also that elderly patients, those with failed prior prolapse procedures, and those with prior pelvic surgery or radiation should be considered for this procedure.155,193

Lechaux and coworkers reviewed their 85 patients who underwent this operation.170 Their complication rate was

14%, with one death. The recurrence rate was 13.5%, with approximately two-thirds achieving improved bowel control. Plusa and colleagues evaluated physiologic changes following this procedure in 19 women.245 There were no significant changes in anal sphincter pressures, but there was an observed decrease in the volume required for first rectal sensation, as well as a decline in the maximum tolerated rectal volume. Furthermore, rectal compliance was reduced in addition to improved rectal sensation. Tsunoda and associates noted a 13% recurrence rate in their 31 patients (median follow-up, 39 months).320 They also performed physiologic assessment and found a statistically significant improvement in squeeze pressures, volume at first sensation, and maximum tolerable volume. The preoperative incontinence score improved from 11.5 to 6.0 (P < .0001). Watts and Thompson performed the Delorme’s procedure on 101 patients with “full-thickness rectal prolapse” and followed them for more than 1 year.329 Thirty-eight had no recurrence, 33 died without recurrence, and 30 developed a recurrence (30%).

14%, with one death. The recurrence rate was 13.5%, with approximately two-thirds achieving improved bowel control. Plusa and colleagues evaluated physiologic changes following this procedure in 19 women.245 There were no significant changes in anal sphincter pressures, but there was an observed decrease in the volume required for first rectal sensation, as well as a decline in the maximum tolerated rectal volume. Furthermore, rectal compliance was reduced in addition to improved rectal sensation. Tsunoda and associates noted a 13% recurrence rate in their 31 patients (median follow-up, 39 months).320 They also performed physiologic assessment and found a statistically significant improvement in squeeze pressures, volume at first sensation, and maximum tolerable volume. The preoperative incontinence score improved from 11.5 to 6.0 (P < .0001). Watts and Thompson performed the Delorme’s procedure on 101 patients with “full-thickness rectal prolapse” and followed them for more than 1 year.329 Thirty-eight had no recurrence, 33 died without recurrence, and 30 developed a recurrence (30%).

FIGURE 21-17. Delorme procedure. A: The mucosa is circumferentially incised above the dentate line. B: Submucosal stripping is carried out as far cephalad as is possible. |

Restoration of the Pelvic Floor (Historical)

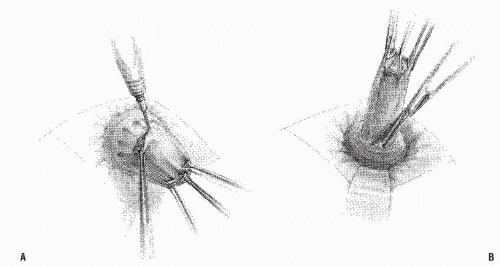

Restoration of the pelvic floor by means of plicating the levators and obliteration of the pouch of Douglas was initially described by Graham in 1942.101 Others have advocated this

operation alone or in combination with other modes of surgical therapy.7,80,81,134,232 The procedure can be accomplished through the abdomen or the perineum (see also Chapter 16) or after removing the coccyx or lower sacrum.134 Plicating the levators transabdominally can be performed anterior or posterior to the rectum, although the latter may be technically difficult to accomplish (Figure 21-19). If the surgeon were to use plication of the levators as the sole method of treatment for rectal prolapse, the incidence of recurrence would be prohibitively high.

operation alone or in combination with other modes of surgical therapy.7,80,81,134,232 The procedure can be accomplished through the abdomen or the perineum (see also Chapter 16) or after removing the coccyx or lower sacrum.134 Plicating the levators transabdominally can be performed anterior or posterior to the rectum, although the latter may be technically difficult to accomplish (Figure 21-19). If the surgeon were to use plication of the levators as the sole method of treatment for rectal prolapse, the incidence of recurrence would be prohibitively high.

ROSCOE REID GRAHAM (1890-1948)

|

Graham was born in the village of Lobo, near London, Ontario, Canada, the son of a country physician. He received his medical degree at the University of Toronto, and after a year of internship went abroad to do postgraduate work in Great Britain and on the European continent. He served with the Royal Canadian Medical Corps in England during World War I and returned to resume his practice at Toronto General Hospital, ultimately becoming director of the Division of Surgery. He is credited with being the first to remove an islet cell tumor of the pancreas, and at the time was the youngest surgeon elected to the American Surgical Association.

Transsacral Resection (Historical)

The transsacral operation uses the approach to the rectum described by Kraske for resection of rectal cancer (see Chapter 24).157 This procedure has been advocated by Davidian and Thomas and by Jenkins and Thomas.58,134

An incision is made overlying the sacrum and coccyx, and the latter is disarticulated and removed. The levator ani muscles are divided to expose the rectum. The peritoneum is incised anteriorly and the rectum fully mobilized. The redundant colon is liberated and delivered through the sacral wound (Figure 21-20A). The levator ani muscles are approximated anterior to the rectum (Figure 21-20B), the peritoneum is closed, and resection of the redundant bowel is carried out. After the anastomosis is completed, all wounds are primarily closed.

The theoretical advantages of this procedure are that the operation does not require a laparotomy and that the levator ani muscles are reconstituted, thus narrowing the defect in the pelvic floor. The pouch of Douglas is obliterated, and the rectum is secured posteriorly. The major disadvantage is that the patient has a painful sacrococcygeal wound that is subject to infection. The possibility of a fecal fistula, although not noted by Davidian and Thomas, is well recognized when this procedure has been undertaken for other indications. The authors reported 30 patients who underwent this operative approach; neither mortality nor recurrence occurred.58 There have been no published reports of this esoteric operation for many years.

Gant-Miwa Procedure

For an operative approach that is virtually unheard of in the West, it is interesting to note that the Gant-Miwa procedure has been the most common surgical option employed for the treatment of rectal prolapse in Japan.343 The concept is simply the placement of 20 to 40 absorbable sutures that incorporate the mucosa and submucosa, thereby creating tags or lumps from the apex of the prolapsed rectum to 1 cm from the dentate line. The sutures should be placed at least 5 mm apart in order to avoid mucosal ulceration or necrosis. Gant introduced the procedure in Japan in the 1920s, but the recurrence rate was prohibitively high. Miwa suggested combining the operation with an anal encirclement to reduce the likelihood of recurrence. Still, even with the combined operation (i.e., the Gant-Miwa Procedure), recurrence rates in the range of approximately 15% are considered acceptable in Japan.

Abdominal Procedures

Historical

Teflon or Marlex Sling Repair (Ripstein Operation) (Historical).

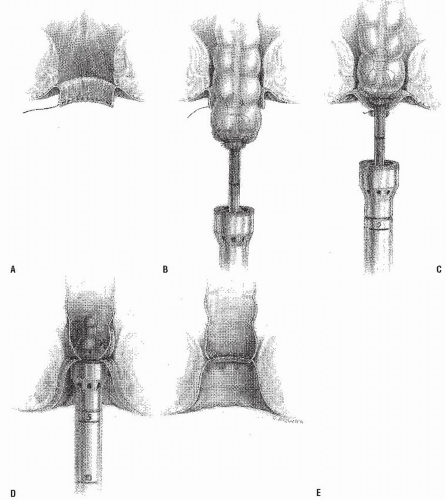

Arguably, this was the most common surgical approach for the treatment of rectal prolapse in the United States until the advent of sutured posterior rectopexy. The procedure was

described initially by Ripstein in 1965.259 After mobilization of the rectum, a rectopexy is carried out using a sling of Teflon, Marlex, or Gore-Tex placed around the anterior surface of the rectum and fixed to the sacrum on each side.

described initially by Ripstein in 1965.259 After mobilization of the rectum, a rectopexy is carried out using a sling of Teflon, Marlex, or Gore-Tex placed around the anterior surface of the rectum and fixed to the sacrum on each side.

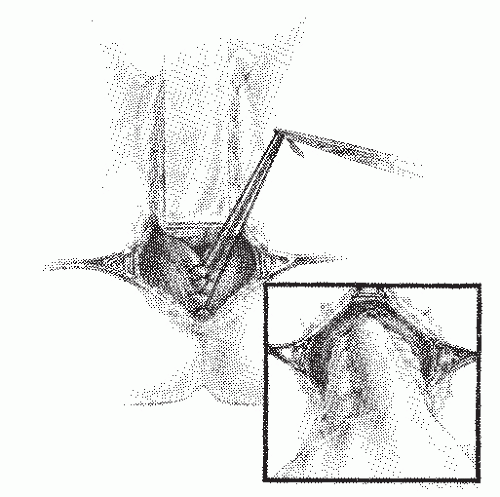

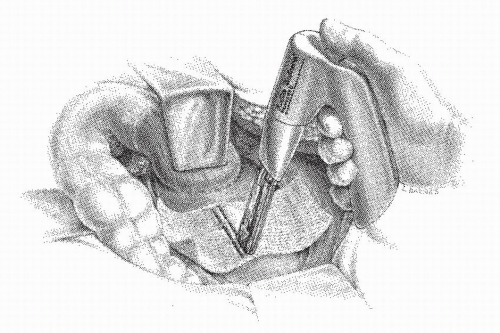

Securing the Teflon mesh (or Marlex or Gore-Tex) to the sacrum can be accomplished in one of three ways. Sutures can be placed into the periosteum of the sacrum approximately 1 cm to the right of the midline by using a half circle Mayo trocar point needle. Three or four nonabsorbable sutures are used (Figure 21-21A). The mesh is trimmed to approximately 4 cm wide and secured in place along the right side of the sacrum (Figure 21-21B). At this point in the operation, it is important for the assistant to maintain proximal traction while the mesh is anchored to the muscularis propria of the rectum. If the rectum is not under cephalad tension and if redundant rectum is left below the mesh, a prolapse will recur. Nonabsorbable sutures are placed from the mesh into the rectal wall (Figure 21-21C). After the mesh has been laid around two-thirds of the bowel, the redundant material is appropriately trimmed so that it can be secured without tension (Figure 21-21D). Sutures are then anchored in the sacrum on the left side and placed into the mesh. An approximately 1-cm

defect is present posteriorly (Figure 21-21E). The remaining sutures on the left side are placed through the mesh and in the muscularis of the bowel (Figure 21-21F). Another method of securing the mesh is to place a single row of sutures into the midline of the sacrum. The middle of the mesh is sutured into place and the material brought onto either side of the rectum (Figure 21-22). With proximal traction maintained on the rectum, the mesh is anchored, leaving a 1-cm defect anteriorly (Figure 21-22, inset). This is a simpler technique than the former, but it has the potential risk of leaving only a solitary row of sutures posteriorly with which to hold the rectum to the sacrum. A simpler modification for attaching the mesh to the sacrum has been proposed by Nicosia and Bass.218 A fascial stapler was used successfully in 12 patients to accomplish fixation expeditiously and with essentially no risk of inducing hemorrhage (Figure 21-23).

defect is present posteriorly (Figure 21-21E). The remaining sutures on the left side are placed through the mesh and in the muscularis of the bowel (Figure 21-21F). Another method of securing the mesh is to place a single row of sutures into the midline of the sacrum. The middle of the mesh is sutured into place and the material brought onto either side of the rectum (Figure 21-22). With proximal traction maintained on the rectum, the mesh is anchored, leaving a 1-cm defect anteriorly (Figure 21-22, inset). This is a simpler technique than the former, but it has the potential risk of leaving only a solitary row of sutures posteriorly with which to hold the rectum to the sacrum. A simpler modification for attaching the mesh to the sacrum has been proposed by Nicosia and Bass.218 A fascial stapler was used successfully in 12 patients to accomplish fixation expeditiously and with essentially no risk of inducing hemorrhage (Figure 21-23).

CHARLES BENJAMIN RIPSTEIN (1913-2003)

|

Charles Ripstein was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, December 13, 1913, one of four children of a whiskey manufacturer. He wished to be an engineer but developed tuberculosis. He moved to Arizona to recuperate and while there attended the University of Tucson. Because of his own illness, he became interested in studying medicine. He then returned to Canada to enter medical school at McGill University, graduating first in his class. One of his classmates was Rupert Turnbull, his lifelong friend. Upon graduation in 1940, he enlisted in the Canadian Air Force as a flight surgeon and flew many bombing missions over Europe. Following the war, he returned to McGill for his surgical residency. His primary interest at that time was cardiothoracic surgery. He accepted a position as professor of thoracic surgery at Downstate Medical Center (Brooklyn, New York) in 1949. During this time, he developed an extensive clinical cardiac surgery, teaching, and research program. In 1955, he accepted the position as the first professor of surgery at the newly established Albert Einstein College of Medicine (New York) and chief of General Thoracic Surgery, Brookside and Jacobi Hospitals. During the following decade, he developed a particular interest in colon and rectal surgery and ultimately became a fellow of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. In 1972, he moved to Miami, Florida, where he practiced colon and rectal surgery until he retired in his early 80s. (With appreciation to Linda Ripstein Dresnick, MD and Rene F. Hartmann, MD.)

Following suspension, it is not necessary to reperitonealize the floor of the pelvis, but it can be done if the surgeon so wishes. If hemostasis is secured, pelvic drainage is not necessary, and with the foreign material, the presence of a drain can pose a particular hazard for infection. However, when venous bleeding has been encountered, a closed suction drain may be placed into the pelvis and brought out through a stab wound in the left lower quadrant. This is usually maintained for 2 to 3 days.

Kuijpers and Mollen routinely perform a rectovaginoplasty in patients with complete prolapse.158 These surgeons believe that the incidence of concomitant genital prolapse is “at least 25%” or will surely develop later. They further emphasize that the pouch of Douglas should be obliterated.

Sepsis is an unusual complication of mesh repair, but when it occurs it is extremely difficult to treat. Removal of the mesh inevitably becomes necessary, a technical tour de force that may lead to the requirement for a bowel resection. It is primarily because of the risk of entering the bowel during some phase of the procedure that a mechanical preparation has been strongly suggested. If the lumen is breached, the surgeon is advised to carry on with a resection rather than risk insertion of foreign material in a contaminated field.

The mean follow-up period was 46 months in the Lahey Clinic series, with 35 patients available for evaluation more than 5 years later.139 Bowel management and incontinence remained persistent problems after the prolapse was corrected. Approximately one-third complained of difficulty in regulating bowel function after the repair, and 11% reported incontinence or soiling. Of course, bowel function and incontinence problems are common complaints prior to surgery. The habits of excessive straining to pass stool and dependence on laxatives are often long-standing and not remedied by anatomic correction of the prolapse.

Gordon and Hoexter, in a study based on a questionnaire sent to members of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, were able to gain information on 1,111 Teflon sling repairs performed by 129 surgeons.99 The overall complication rate was 16.5%, with a recurrence of 2.3%. Fecal impaction was seen in 6.7%. It was the opinion of the authors that the complications seemed to be related primarily to applying the mesh too tightly around the rectum. The complication rate seems to diminish as the surgeon’s experience increases.

Holmström and associates reported their initial experience with the Teflon sling repair in 59 patients.121 The operative mortality was high (5%). However, in 2 of the 3 patients who died, the cause of death was coronary artery disease. The recurrence rate was 5.4% during a mean observation period of 5 years. A later report from the same institution included 108 patients, 97 of whom were available for evaluation.122 The recurrence rate in this study was 4.1%. The proportion of continent patients increased from 33% preoperatively to 72% postoperatively. However, problems with defecation were a major source of dissatisfaction; difficulties increased from 27% preoperatively to 43% postoperatively.

Biehl and colleagues reported on their experience at the Ochsner Clinic and compared it with the Altemeier, sigmoidectomy, and Thiersch procedures that had been formerly used.25 The Ripstein operation was associated with a lower recurrence rate and a lower morbidity rate. Launer and coworkers reported the Cleveland Clinic experience with the Teflon sling repair.168 Although there was no operative mortality in 57 patients, there was a high morbidity rate (26%). Seven (14%) developed recurrent mucosal prolapse, and six patients (12%) had a full-thickness recurrence. Despite the somewhat disappointing results, the authors believed that the Ripstein procedure remained the treatment of choice for rectal prolapse. A later report from the same institution involved 142 patients.310 The recurrence rate had fallen to 8%. About one-half experienced improvement in bowel control, but persistence or worsening of constipation was more common than after resection. Approximately onethird remained dissatisfied with the functional results despite anatomic correction of the prolapse.

Late Complications.

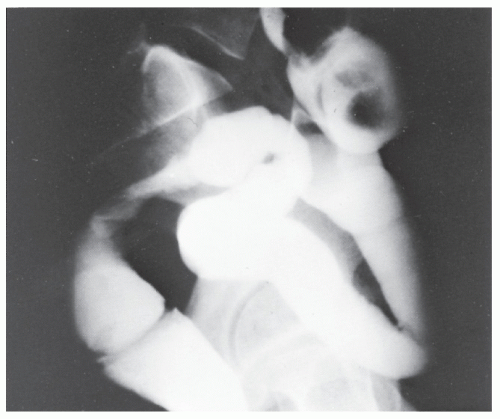

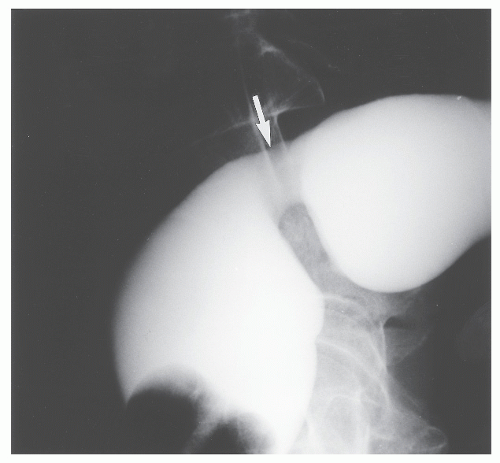

Lescher and colleagues reported the late complications of Teflon sling repair, including when the original procedure was performed elsewhere.173 Rectal stricture (Figure 21-24) developed in five patients. These individuals had in common a troublesome history of bowel management problems, specifically severe constipation that antedated insertion of the Teflon sling. Patients with rectal stricture also had a longer history of prolapse (79 vs. 37 months). Barium enema examination showed stenosis in all five of these individuals (Figure 21-25), ranging from a diameter of 3 to 19 mm. The presence of narrowing was also identified by proctosigmoidoscopy.

McMahan and Ripstein confirmed that difficulties have arisen with Teflon as the suspension material.197 They recommend Gore-Tex as being ideal because of its inert properties and its porous structure, which allows tissue incorporation. They also place the sling posteriorly, leaving the anterior rectal wall free to distend. Others have reported the results of polypropylene mesh with no recurrences in a series of 23 patients.177

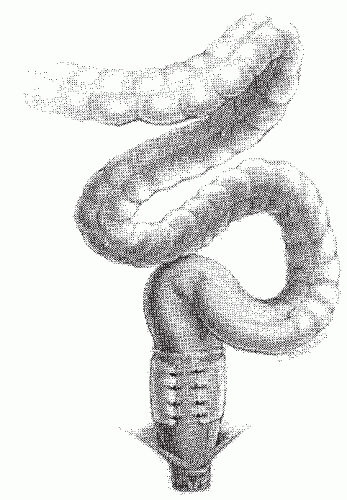

Clearly, constipation is not improved by the Teflon sling repair. On the contrary, abdominal pain, distension, and constipation may be exacerbated by the now-exaggerated redundancy of the sigmoid colon (Figure 21-26).35,344 Sigmoid volvulus has been reported to occur under these circumstances. In some individuals who present with obstructive symptoms relatively soon after the operation, faulty technique must be assumed. However, fibrotic reaction secondary to the mesh must also be considered as a possible contributing factor. In any patient with chronic constipation, particularly with a history of long-standing rectal prolapse, serious consideration should be given to performing an anterior resection initially. At the very least, these individuals should undergo careful preoperative investigation to identify those who have associated disturbances of function (e.g., slow-transit constipation, obstructed defecation).74

Recurrent rectal prolapse after Teflon sling repair may be related to faulty surgical technique. The mesh may not be secured adequately to the presacral fascia or bone. In addition, as has been previously stated, when traction on the rectosigmoid is not maintained while the sling is inserted, the mesh will not be anchored sufficiently low on the rectum. The error is more likely to occur in a male whose pelvis is narrow and in whom mobilization and suture placement are more difficult.

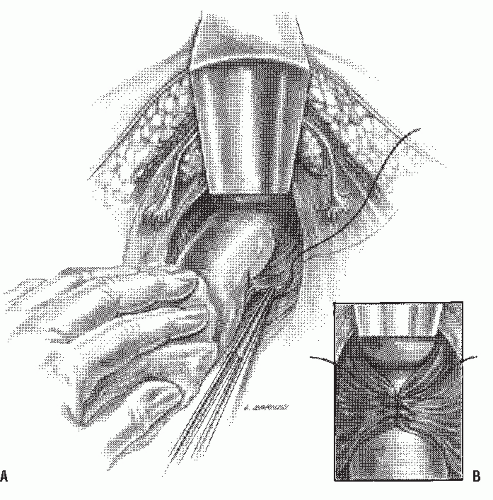

Ivalon Sponge Implant or the Wells Operation (Historical).

The use of Ivalon sponge as a wrapping about the rectum was initially described by Wells in 1959330; it has been enthusiastically advocated, primarily by the British and the Canadians.5,15,31,32,41,189,195,205,239,266,297 However, because polyvinyl alcohol (i.e., Ivalon) has not been approved for this purpose in the United States, there is no American experience. The Ivalon sponge implant operation basically consists of the implantation of a synthetic polymer around the rectum. After full mobilization of the rectum, the appropriately tailored sponge is sutured to the sacrum in the posterior midline (Figure 21-27A,B), not unlike the modified Teflon sling operation. It is then wrapped around the rectum, leaving a defect in the anterior midline (Figure 21-27C).

Results of this procedure on 26 patients were reported by Boutsis and Ellis.32 One operative death occurred, but no instance of pelvic sepsis or wound complication had developed. Follow-up study revealed nine mucosal recurrences— an incidence of 35%. Complete rectal prolapse developed in 11.5%. Stewart reported using this procedure in 41 patients;

no operative deaths occurred, complete recurrence developed in 3 patients (7%), and a mucosal recurrence was noted in 10 individuals (24%).297 McCue and Thomson identified two recurrences in 53 patients (3.8%).194 Boulos and associates reported 25 patients younger than 40 years of age who were followed for at least 5 years.31 Twenty percent were found to have recurrence. Mann and Hoffman, however, noted no recurrences after 2 years in 44 patients.189 A conscientious effort was made to mobilize the rectum fully, to shorten the lateral ligaments, and to excise the redundant peritoneum. Despite the absence of recurrence, constipation (47%) and incontinence (19%) caused difficult management problems. Rogers and Jeffery evaluated 24 individuals who were treated by concomitant Ivalon sponge rectopexy and postanal repair.263 There was one recurrence (4%), with a maximum of 4 years of follow-up. Every patient was rendered continent in this uncontrolled study.

no operative deaths occurred, complete recurrence developed in 3 patients (7%), and a mucosal recurrence was noted in 10 individuals (24%).297 McCue and Thomson identified two recurrences in 53 patients (3.8%).194 Boulos and associates reported 25 patients younger than 40 years of age who were followed for at least 5 years.31 Twenty percent were found to have recurrence. Mann and Hoffman, however, noted no recurrences after 2 years in 44 patients.189 A conscientious effort was made to mobilize the rectum fully, to shorten the lateral ligaments, and to excise the redundant peritoneum. Despite the absence of recurrence, constipation (47%) and incontinence (19%) caused difficult management problems. Rogers and Jeffery evaluated 24 individuals who were treated by concomitant Ivalon sponge rectopexy and postanal repair.263 There was one recurrence (4%), with a maximum of 4 years of follow-up. Every patient was rendered continent in this uncontrolled study.

FIGURE 21-25. Profound rectal stricture (arrow) can be readily appreciated on this lateral film of the barium-filled rectum. |

FIGURE 21-26. Rectal suspension procedures may exacerbate bowel management difficulties. Note the sigmoid redundancy that may result. |

Allen-Mersh and colleagues noted a statistically significant increase in the prevalence of constipation following this operation.5 One of the possible explanations that they suggest is the increased rectal wall thickness that occurs in some individuals. This may impede the passage of stool through the rectum and result in constipation.

Novell and coworkers performed a prospective, randomized trial of Ivalon sponge and sutured rectopexy (see later).223 At a median follow-up of 47 months, prolapse had recurred in two patients (3%), one in each group; 22% suffered from incontinence, and 40% developed constipation. The authors concluded that the results of rectopexy by suture alone were equivalent to those obtained when Ivalon sponge was implanted, and they concluded that an implant was not necessary.

Although septic problems are not common, removal of the sponge may be quite difficult, particularly when the physician attempts to identify foreign material within an abscess cavity.164 Symptoms of this complication include sacral, coccygeal, or lower abdominal pain, pus per rectum, pus per vaginam, rectal discharge, and fever. No instance of recurrence was reported by the St. Mark’s Hospital group (eight cases) after removal of the implant.266 They recommended that removal of the implant should be performed through the vagina or the rectum if at all possible. The apparent advantage of the Ivalon sponge implant operation is that fecal impaction has not been as great a problem.205,239 However, the incidence of recurrence is higher than that generally reported for the Teflon sling repair and for resection.

Obliteration of the Pouch of Douglas (Historical).

The Moschcowitz procedure was designed on the theory that the cause of rectal prolapse is a sliding hernia. The technique involves the placement of serial purse-string sutures into the floor of the pelvis to obliterate the pouch of Douglas (Figure 21-28). The recurrence rate, however, as reviewed by Theuerkauf and associates, was close to 50%. Although we have had no experience with this technique, the lack of success of others and the theoretical premise on which it is based would seem to imply that the procedure should be abandoned.

Teflon Halter Operation (Historical).

A unique approach to rectal suspension has been suggested by Nigro (see Biography, Chapter 25).220 He believed the most effective way to correct prolapse was to use a method that most closely simulated the normal anatomy. It was his contention that the most important factor is the angulation and fixation provided by the

pelvic floor musculature, and that maximum support came with contraction of the muscle as it lifted the lower rectum and tilted it forward toward the pubis.219 Accordingly, he designed an intra-abdominal sling approach that suspends the rectum from the pubis. Successful results were experienced in all six patients.

pelvic floor musculature, and that maximum support came with contraction of the muscle as it lifted the lower rectum and tilted it forward toward the pubis.219 Accordingly, he designed an intra-abdominal sling approach that suspends the rectum from the pubis. Successful results were experienced in all six patients.

ALEXIS VICTOR MOSCHCOWITZ (1865-1937)

|

Moschcowitz was born in Giralt, Hungary, and emigrated to the United States at the age of 15. He received a degree in pharmacy in 1885 and then entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, graduating in 1891. He ultimately joined the staff of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City and later became professor of clinical surgery at his alma mater. During World War I, Moschcowitz was a consultant in the Surgeon General’s Office in Washington, DC. His research as a member of the Empyema Commission resulted in a lowered mortality rate from this condition in soldiers. He contributed extensively to the surgical literature, reporting in 1907 an inguinal approach to femoral herniorrhaphy, a procedure that has come to be known as the Moschcowitz operation.

FIGURE 21-27. Technique of Ivalon sponge implant. A,B: Suturing of sponge and anchoring to sacrum. C: Suspension completed. |

The patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position on the operating table. A midline incision is made in the lower abdomen, and the rectum is mobilized in the same manner as that for a Ripstein or Wells repair. Care is taken to avoid injury to the inferior mesenteric vessels. The dissection is carried posteriorly down to the coccyx. The mesh is cut to be approximately 4 cm wide by 20 cm long. The central portion is secured to the rectum with interrupted nonabsorbable sutures. It is then sutured to the posterior and lateral walls of the rectum as low as possible.

The space of Retzius, in front of the bladder and close to the pubic rami, is opened. A long curved clamp is placed into this space and directed downward and posteriorly to the presacral space. The mesh is then grasped and pulled forward to lie on the pubic bone. The same is done on the contralateral side. Each end is then secured to the pubic ramus with

interrupted nonabsorbable sutures. The length of graft is determined by holding it to the pubic bone with just enough tension to prevent slack (Figure 21-29). The presacral space is left open, and the abdomen is closed without drainage. Postoperative care is essentially the same as that for the conventional operation.

interrupted nonabsorbable sutures. The length of graft is determined by holding it to the pubic bone with just enough tension to prevent slack (Figure 21-29). The presacral space is left open, and the abdomen is closed without drainage. Postoperative care is essentially the same as that for the conventional operation.

FIGURE 21-28. The Moschcowitz procedure involves the obliteration of the pouch of Douglas by serial purse-string sutures. |

Greene reported 15 patients who underwent this operation.103 There was no mortality, no operative morbidity, and no recurrence with a minimum follow-up of 6 months. Severe incontinence was corrected in all but one patient, and this person was improved. There were no problems with sexual function or micturition. Greene believed that the particular advantage of this operation was on the improvement in continence. This operation seems to be no longer performed.

Combined Abdominal and Perineal Operation (Historical).

Dunphy reported a combined abdominal and perineal operation for rectal prolapse.80 The perineal operation is essentially the same as that described by Altemeier and colleagues.8 The abdominal operation, however, is accomplished several days later. Full mobilization of the rectum is carried out, and a plication of the ligamentous structures lateral to the rectum is performed. The pouch of Douglas is obliterated in the manner of Moschcowitz. Dunphy described this technique and results of treatment in four patients; no recurrence was noted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree