Abdominal, flank, or pelvic pain

Vomiting

Abdominal distention, bloating, or increased girth

Evaluation for and follow-up of bowel obstruction or nonobstructive ileus

Constipation

Diarrhea

Palpable abdominal mass or organomegaly

Follow-up of the postoperative patient

Blunt or penetrating abdominal trauma

Search for foreign bodies

Assessment of the GI tract for residual contrast which can interfere with another imaging study

Evaluation of medical device position

Evaluation of pneumoperitoneum

It is important to remember that plain films are not used as a screening tool and when used as such may contribute to increased radiation exposure for little diagnostic yield. If the clinical scenario suggests a diagnoses which is better imaged with a different radiologic modality, the alternate imaging study should be used as the initial or only examination for that patient.

Plain abdominal films are useful to the colon and rectal surgeon to identify foreign bodies, check the position of drains and catheters, evaluate changes or abnormalities in intestinal gas distribution, and occasionally identify skeletal or mucosal changes associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

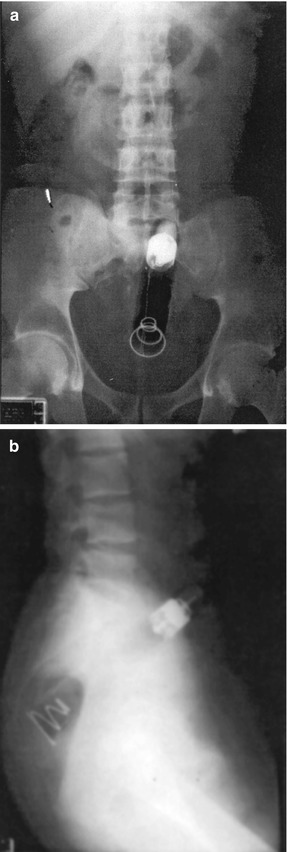

Plain abdominal films not only document the proximal extent of the object but can determine the number, size, and shape of the foreign body (Fig. 6.1a, b). Gas collections may be extraperitoneal or intraperitoneal. Extraperitoneal collections in the soft tissue of the abdominal wall may reflect a necrotizing infection or recent intervention such as surgical incision.

Fig. 6.1

(a) Radiograph of rectal foreign body (anterior posterior). (b) Radiograph of rectal foreign body (lateral)

Intraperitoneal air may be located outside the intestinal lumen (free air), within the wall of the bowel, or within the confines of the bowel wall.

Appropriate localization of abdominal gas collections along with clinical correlation assists the clinician in distinguishing a benign condition from a surgical emergency.

Pneumoperitoneum or air outside the confines of the bowel wall is diagnostic of a perforated viscus and can be diagnosed with high sensitivity using an upright chest film.

If the patient has peritonitis or is extremely ill and cannot sit upright, a left lateral decubitus film can be obtained.

The left lateral decubitus film in the expiratory phase or the upright chest in the midinspiratory phase have a high sensitivity and can be diagnostic of as little as 1 cm3 of free intraperitoneal air.

The left lateral decubitus film is preferred to the right, because it allows air movement between the liver and right hemidiaphragm where it is easily imaged and not confused with the gastric bubble.

It is important to maintain the left lateral decubitus position for at least 5–10 min prior to imaging in order to allow migration of air.

Diagnostic signs of free intraperitoneal air include:

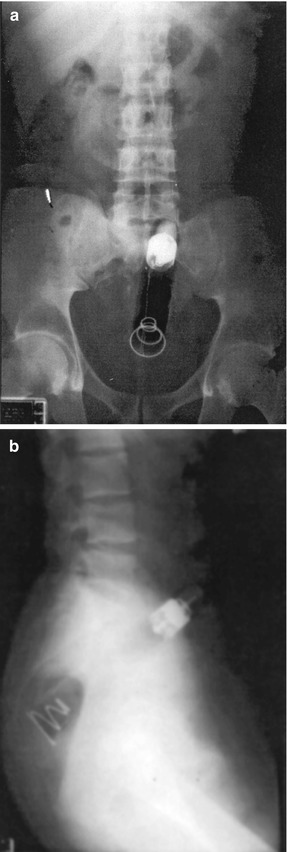

A right upper quadrant gas sign (Fig. 6.2a) is a triangular or linear gas collection which has an oblique (superomedial to inferolateral) orientation between the liver and right hemidiaphragm.

Fig. 6.2

(a) Upright radiograph of the abdomen demonstrates a collection of air within the peritoneal space between the liver and the diaphragm (white arrow). (b) Plain radiograph demonstrates the “Rigler” sign or “double lumen” sign (gas on both sides of the bowel wall (white arrow))

Rigler’s sign (Fig. 6.2b), outlining of both the mucosal and serosal sides of the bowel wall with associated bowel wall thickening (1–8 mm), is also indicative of free intraperitoneal air.

Other less commonly seen diagnostic signs include the falciform ligament sign (a thin linear soft tissue density in the right upper quadrant caused by free intraperitoneal air lining both sides of the falciform ligament), the football sign (visualization of gas anterior to loops of bowel within the central abdomen), and the inverted V sign (visualization of the medial umbilical folds in the pelvis).

A diagnosis of free intraperitoneal air must always be correlated with the clinical condition of the patient. For instance, free intraperitoneal air can be a normal finding after surgery.

Free air is typically reabsorbed over several days following surgery but reabsorption may be delayed in the recumbent or thin patient.

Increasing amounts of air imaged over time or in association with increasing abdominal pain may be indicative of an anastomotic leak or intestinal perforation.

In addition, various conditions may be mistaken for free air:

Chilaiditi syndrome is the interposition of the colon between the liver and diaphragm and can mimic the finding of pneumoperitoneum on plain abdominal films.

Extraluminal air may also be located within a loculated abscess cavity, within solid organs that do not typically contain air, in the venous system, or within the bowel wall.

Portal venous air is peripherally located air, which may have entered the portal venous system as a result of bowel ischemia and necrosis or a gas-producing bacterium.

In contrast, pneumobilia or air within the biliary tract is centrally located and can result from a cholecystoduodenal fistula or from an endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Finally, linear air within the bowel wall (pneumatosis intestinalis) may result from bowel ischemia and necrosis, while cystic air collections within the bowel wall signify a benign condition called pneumatosis cystoides.

Determination of intraluminal bowel gas patterns can help differentiate a small from large bowel obstruction or a bowel obstruction from a paralytic ileus.

Bowel dilation is identified by the 3, 6, 9 rule. The small bowel is dilated when the diameter is 3 cm, the colon when it reaches 6 cm, and the cecum when it dilates to 9 cm.

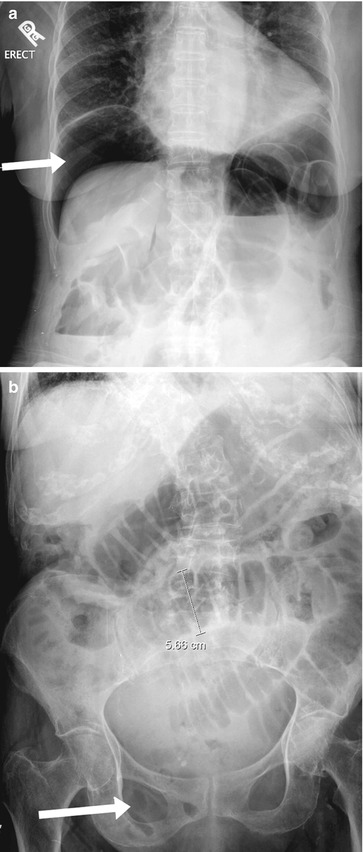

The small bowel can be differentiated from the colon by valvulae conniventes which cross the entire bowel loop and are more narrowly spaced compared to the haustra of the colon which are thicker, further apart, and only extend halfway across the colon diameter. In addition, dilated small bowel loops may form a stepladder appearance when dilated from obstruction (Fig. 6.3).

Fig. 6.3

Plain film of small bowel obstruction with dilated small bowel loops, forming a stepladder

The valvulae conniventes may trap air between them as the obstructed small bowel fills with fluid giving a string of beads appearance. This finding is sensitive for a high-grade small bowel obstruction (SBO). However, other signs of obstruction can be misleading.

Air-fluid levels may be indicative of an SBO, gastroenteritis, or paralytic ileus. Ileus may be differentiated from obstruction by air found throughout the small bowel and colon (Fig. 6.4).

Fig. 6.4

Small bowel obstruction air-fluid levels

In contrast, a completely obstructed bowel may be void of air distal to the obstruction. In a partial or early bowel obstruction, distal air evacuation may not be present and the distinction between ileus and obstructions is impossible.

Large bowel obstructions clinically appear like a distal SBO. On plain abdominal films the colon alone may be dilated if the ileocecal valve is competent (Fig. 6.5). This causes the cecum to dilate. Acute cecal dilation beyond 12 cm places the patient at risk of perforation. In the setting of an incompetent ileocecal valve, air refluxes proximally into the small bowel which can make it difficult to distinguish between a paralytic ileus and distal bowel obstruction (Fig. 6.6).

Fig. 6.5

Large bowel obstruction secondary to sigmoid cancer. Competent ICV

Fig. 6.6

Large bowel obstruction secondary to sigmoid cancer. Incompetent ICV

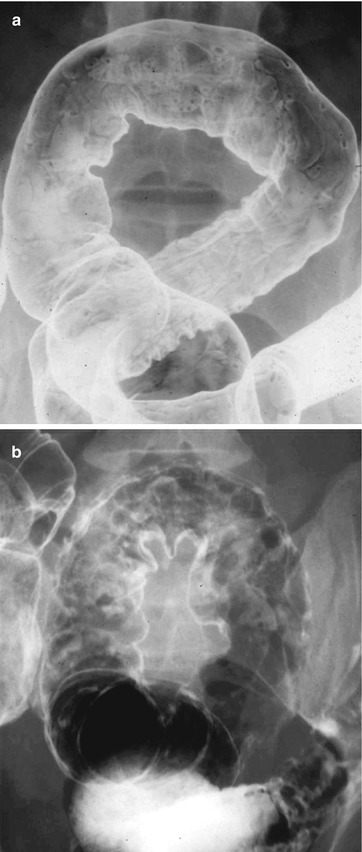

Volvulus in the cecum or sigmoid gives rise to a closed loop obstruction within the colon and can result in characteristic findings on abdominal plain films.

The classic finding of a sigmoid volvulus is a U-shaped loop of colon projected toward the right upper quadrant in the shape of a “bent inner tube.” In the middle of the sigmoid loop, the medial walls of the obstructed sigmoid colon point into the pelvis (Fig. 6.7). These findings are also associated with a dilated colon and small bowel proximal to the sigmoid.

Fig. 6.7

Plain film of sigmoid volvulus

Cecal volvulus is characterized by a dilated cecum in the upper left quadrant with a “coffee bean” or “kidney” shape because of the medially placed ileocecal valve (Fig. 6.8).

Fig. 6.8

Plain film of cecal volvulus

Finally, the abdominal radiograph can reveal changes in mucosal contour and thickness. Normal bowel wall thickness is less than 2 mm. However, various forms of colitis may give rise to bowel wall thickening and mucosal irregularity.

Thumbprinting is a radiographic sign that signifies bowel wall and mucosal edema and in the setting of colon dilation may signify the presence of toxic megacolon with risk of impending perforation.

Chronic mucosal inflammation may lead to haustral blunting and a tubular burned out colon from longstanding colitis (Fig. 6.9).

Fig. 6.9

Plain film of chronic burned out colitis

Contrast Studies

Contrast Enemas

Contrast enemas can be performed as a single-contrast or double-contrast enema.

The single-contrast enema is performed by filling the colon and rectum with barium or a water-soluble agent through a rectal catheter.

In double-contrast enemas or air-contrast enemas, barium is instilled into the colon and rectum until the mid-transverse colon is reached. The colon is then drained of excess barium and air is instilled to allow luminal distention and prevent mucosal wall apposition.

The radiologist can then change the position of the patient and use fluoroscopic guidance to obtain images of the colonic and rectal mucosa throughout its length and in multiple projections without overlap. The double contrast provides mucosal coating and detail that cannot be seen in single-contrast studies.

Careful technique with mucosal coating, adequate distention, and numerous projections allow discrimination of mucosal abnormalities with the double-contrast enema.

The limitations of a contrast enema need to be considered prior to subjecting the patient to this study. In order to visualize the mucosa, the patient must undergo a complete bowel preparation.

If a patient does not have mobility to change position on the fluoroscopy table or does not have enough rectal tone to hold the contrast enema, the mucosal coating and projections obtained will be of limited diagnostic value.

An incompetent ileocecal valve may allow reflux of contrast into the small bowel and further obscure colonic findings.

The rectal catheter may obscure the distal rectum so that internal hemorrhoids or a distal rectal cancer cannot be appropriately discriminated.

Finally, there is a risk of perforation with this study. Because barium causes an intense inflammatory response within the peritoneal cavity, in clinical situations for which intestinal continuity is in question or when the bowel wall may be weakened, a water-soluble contrast agent should be used.

These scenarios include question of anastomotic integrity, evaluation of a large bowel obstruction, acute colitis, recent snare or forceps biopsy of the colon wall, and suspicion of colonic fistulas. In comparison to barium studies, water-soluble enemas do not coat the mucosa and do not discriminate mucosal changes.

The double-contrast technique can be used to detect mucosal disease in an elective setting (the evaluation of colonic polyps and cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulosis, and other mural abnormalities like lipomas, lymphoma, and endometriosis).

The double-contrast enema has a sensitivity of 50 % for polyps and cancer less than 1 cm in size and 90 % sensitivity for those greater than 1 cm.

Increasing size, ulceration, and circumferential involvement increase the possibility that a polyp has an underlying malignancy.

Semiannular lesions, which are seen on contrast enema with abrupt transition from normal to irregular mucosal patterns, shelf-like overhanging borders, and circumferential bowel narrowing, are characteristic of an apple core lesion and are diagnostic of cancer (Fig. 6.10). In comparison, benign strictures from ischemic, infectious, or inflammatory etiologies have smooth tapering borders.

Fig. 6.10

ACE of annular cancer and “apple core sign”

Overall, double-contrast barium enema has a positive predictive value of 96 % for a malignant stricture and 84–88 % for a benign stricture. Double-contrast barium enema has been recommended as one screening modality for patients greater than 50 years of age at average risk of colon and rectal cancer.

Double-contrast barium enema can also be diagnostic in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease. It can be used to differentiate Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis, define the extent and severity of disease burden, as well as visualize complications of the disease. In acute ulcerative colitis, the mucosa appears stippled with shallow punctuate ulceration (Fig. 6.11a).

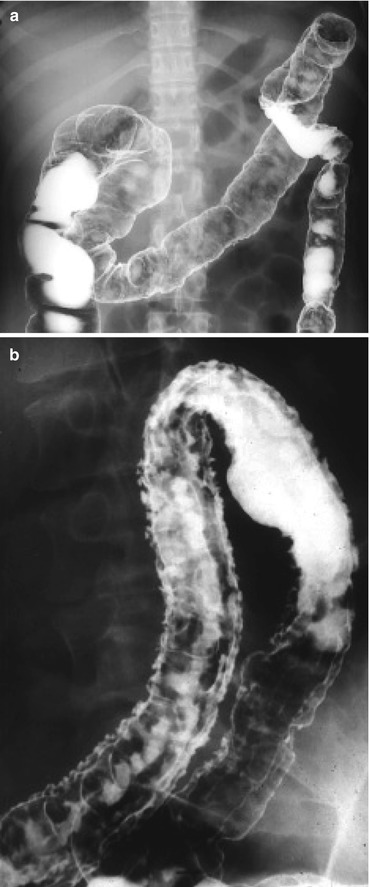

Fig. 6.11

(a) Contrast enema of ulcerative colitis showing stippling ulcers or early colitis. (b) Contrast enema of ulcerative colitis with pseudopolyps

As the inflammation progresses, the ulcers enlarge as crypt abscess ruptures and exposes the submucosa leading to pseudopolyps, which appear as irregular mucosal projections on the contrast enema (Fig. 6.11b).

Eventually, there is loss of mucosal detail and haustral folds, which cause a tubular or lead pipe appearance of the colon (Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.12

Contrast enema of chronic ulcerative colitis

Strictures from ulcerative colitis appear as smooth, symmetric, and circumferential colonic narrowing.

In Crohn’s disease, the mucosal changes are not continuous and are deeper than the changes seen in ulcerative colitis. Early aphthous ulcers appear as shallow depressions with a radiolucent halo (Fig. 6.13a).

Fig. 6.13

(a) Contrast enema of Crohn’s disease showing ulcers. (b) Contrast enema of Crohn’s with fissures and long linear ulcers

As Crohn’s disease progresses, the ulcers widen and coalesce as the muscle in the bowel wall is penetrated. This leads to cobblestoning, which appears as irregular white stripes within the colon wall on contrast enema (Fig. 6.13b).

Deep linear ulceration along the mesenteric border causes “rake” or “bear claw” ulcers that can cause stricturing from transmural fibrosis.

Strictures from Crohn’s disease appear as noncircumferential, irregular areas of narrowing that are centered at the mesenteric edge (Fig. 6.14).

Fig. 6.14

Contrast enema of Crohn’s disease showing a stricture

Complications of Crohn’s disease such as strictures and fistulas are well imaged with the double-contrast barium technique. In contrast, other complications of inflammatory bowel disease are not easily diagnosed with enema studies. In both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, it is difficult to distinguish inflammatory polyps from dysplasia or cancer.

Diverticular disease can also be well characterized with contrast enemas. The size, shape, number, and location of diverticuli are well imaged.

In profile, diverticuli appear flask shaped with a neck, which points away from the colonic lumen. En face diverticuli appear as a white spot or meniscus within the colon lumen (Fig. 6.15). With acute diverticular inflammation, secondary signs of inflammation such as narrowing of the colon lumen from extrinsic compression and mucosal edema are evident.

Fig. 6.15

Barium enema demonstrates a deformed colon wall with diverticular sacs (From Blanchard TJ, Altmeyer WB, Matthews CC. Limitations of colorectal imaging studies. In: Whitlow CB, Beck DE, Margolin DA, Hicks TC, Timmcke AE, editors. Improved outcomes in colon and rectal surgery. London: Informa Healthcare; 2010. p. 97–131. With permission)

Complications of diverticulitis can also be seen. Diverticular perforation results in leaking of extraluminal contrast into the peritoneal cavity, a contained cavity, or a blind sinus that drains back into the colon lumen.

Strictures appear as smooth transitions in colon caliber with intact mucosa.

Abscesses are suggested by a smooth contour defect within the colon lumen, which does not distend with additional air or contrast instillation.

Fistulae between proximal intestinal loops, the vagina, and bladder may also be seen. Barium contrast enema is safe to perform with active diverticular inflammation in the absence of peritonitis. However, the sensitivity of the contrast enema is low and may not be diagnostic in a patient with complicated diverticulitis.

Double-contrast enemas may also reveal colonic lipomas, endometriosis, and lymphoma. Lipomas are seen as a submucosal mass or polypoid lesion with smooth overlying mucosa. The soft pliable nature of the lipoma may be imaged in real time as the barium and air are instilled and show compression of the mass known as the “pillow sign.”

Endometriosis appears as an extracolonic process with intact but bunched up mucosal folds that result in luminal narrowing and in extreme cases scarring and luminal contracture (Fig. 6.16).

Fig. 6.16

Contrast enema showing endometriosis

Lymphoma appears different from adenocarcinoma on a double-contrast enema. In contrast, lymphoma does not narrow the lumen but causes folding and thickening of the mucosa from bowel wall infiltration.

The mucosa maintains a smooth appearance (Fig. 6.17). All these findings on double-contrast enema while, suggestive of a specific diagnosis, require correlation with clinical information to be diagnostic of the condition.

Fig. 6.17

Contrast enema showing colonic lymphoma

Water-soluble enemas do not result in the same mucosal coating and colonic distention that can be achieved with double-contrast enemas. However, water-soluble contrast is not toxic to the peritoneal lining and can therefore be used in clinical situations in which bowel integrity may be compromised.

This includes clinical situations suspicious for colonic obstruction caused by cancer, acute episodes of inflammatory bowel disease, intussusception, volvulus, and fecal impaction.

Water-soluble enemas may also be used for evaluation of anastomotic integrity.

A water-soluble contrast enema demonstrates a spring-coil appearance or crescent sign as contrast gets trapped between the lumens of the two bowel segments and leaves a thin circular line that outlines the proximal bowel in the distal bowel lumen (Fig. 6.18).