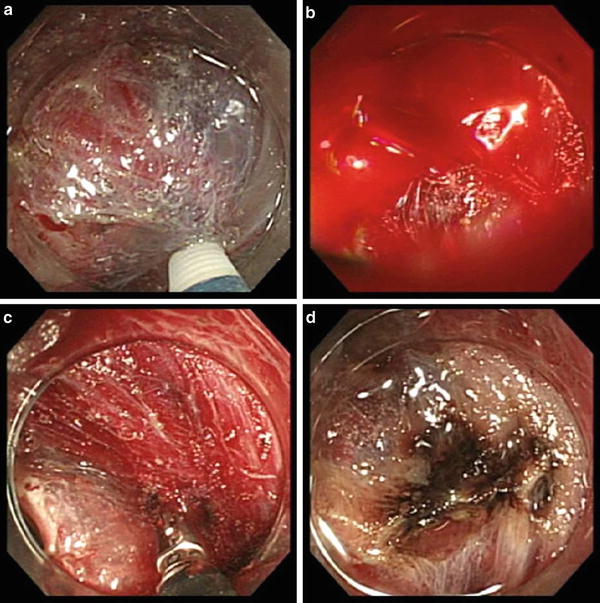

Fig. 19.1

Granular-type laterally spreading tumor in the rectum. (a) After incision of the mucosa. Bleeding from the incision was prevented by controlling the depth of the incision to directly below the muscularis mucosae. A number of transverse vessels are observed in the submucosa within the periphery of the incision. (b) Hemostatic processing of the vasculature. (c) The layers below the transverse vessels and above the muscularis were dissected, and a mucosal flap was formed. (d) Dissection was performed, leaving the perforating branches. In the absence of bleeding, the vessels and the muscle fibers are distinctly visible, and dissection can be performed safely

Hemostasis should be achieved as soon as unforeseeable bleeding or oozing occurs [4]. Hemostasis should be attempted first using the knife with coagulation current [5]. If the bleeding does not stop after two or three attempts at coagulation by knife, hemostatic forceps should be used. Caution is required, as repeated coagulation poses the risk of perforation. Once hemostasis is achieved, dissection should be resumed. However, dissection should never be performed forcefully when bleeding has obscured the tissue layers. Dissection should only be resumed at areas where the muscle layer and vascular plexus are distinctly identifiable, and the indistinct areas should be carefully dissected from both sides of the lesion, where the submucosal layer is clearly visible. At all times, prevent misidentification of layers and ensure dissection is performed at the level between the transverse vascular plexus and muscle fibers (Fig. 19.2). Oftentimes in the colon, especially in the lower rectum, a loose, submucosa-like layer lies between the bundles of the muscle fibers. Mistakes can be avoided if the operator understands this and is aware of this similarity (Fig. 19.3).

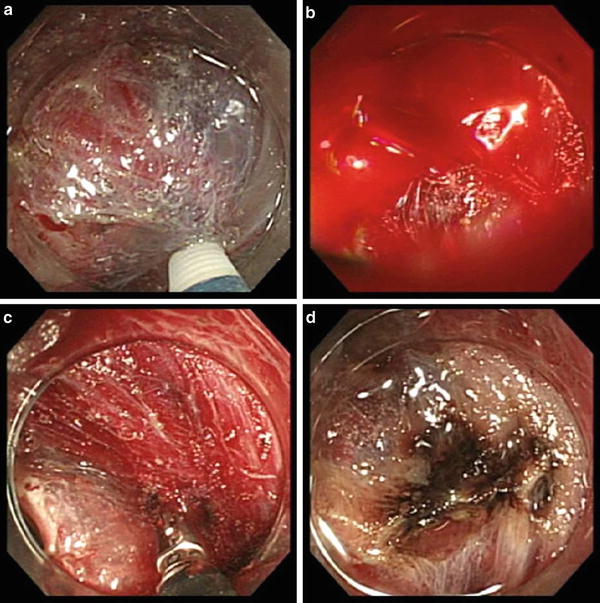

Fig. 19.2

Problems with and countermeasures against intraprocedural bleeding. (a, b) Bleeding immediately compromises visibility. (c) Perform hemostasis as quickly as possible. Delay in hemostasis leads to formation of hematoma in the submucosa, significantly impeding its visualization. (d) Hemostasis was successful, though discoloration of the blood into brown is impeding the identification of the layers. Resume dissection from areas where layers are clearly identifiable (arrow), not from areas with obscured visibility (asterisk)

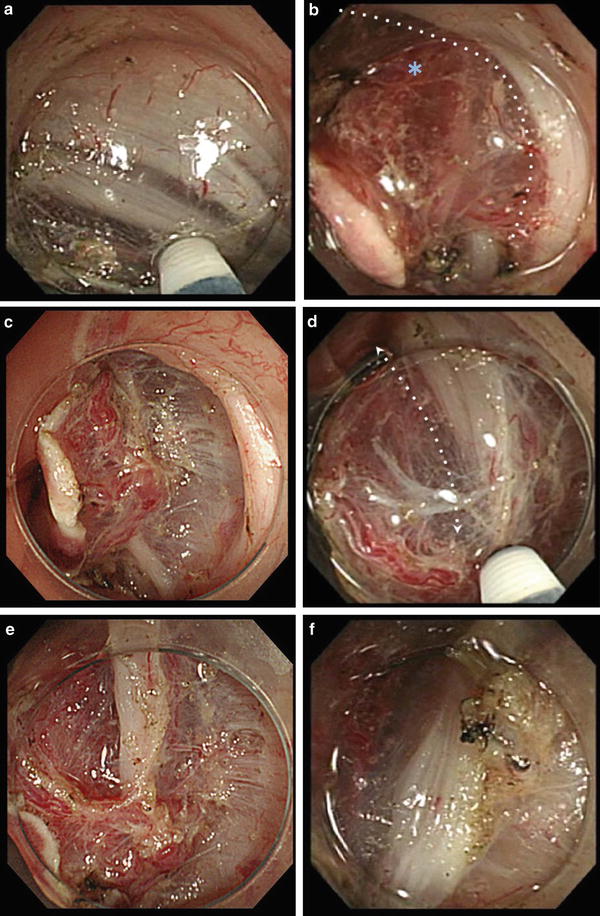

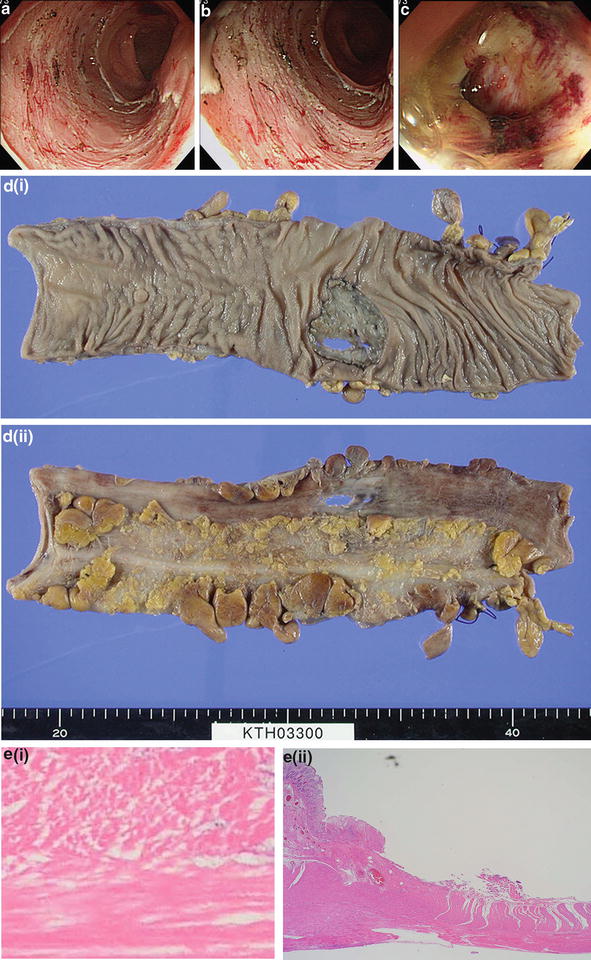

Fig. 19.3

Points of caution in the rectum. (a) There are loose layers of muscle in the rectum (especially in the lower rectum). (b, c) Perforating branches (asterisk) of the rectum are thick and often flow in bundles of 2–3. The sides of the vessels lack the muscularis in a wedge-shaped configuration. If only the muscularis and the loose, submucosa-like tissue are used as landmarks for dissection, there is a risk of losing visual identification of the vasculatures as they tend to get lost in the vast network of muscle fibers. (c, d) Scan the surrounding area and maintain an appropriate dissection depth by noting the space already dissected, the area between the plexus of the transverse vessels and the muscularis. (e, f) Tissue was detached once the area surrounding the perforating branches (asterisk) was dissected in the correct layer. The dissection depth has returned to an appropriate level

Prevention of Postprocedural Perforation

In the colon, the risk of transmural coagulation necrosis and, hence, the risk of postprocedural perforation is set high when coagulation is performed adjacent to or on the thin muscle layers. This phenomenon is equivalent to that observed in perforation cases after the use of hot biopsy and those reported as postpolypectomy coagulation syndrome. It is necessary to avoid coagulation that has the potential to extend to the muscle layer when performing hemostasis, such as by forcefully gripping the point of hemorrhage. Postprocedural perforation has been experienced in a case where coagulation was performed adjacent to the muscle layer in an effort to prevent bleeding after resection (Fig. 19.4). Once we modified the method of preemptive coagulation at the completion of resection, limiting the application of coagulation current only to the transected vessel with pulsatile movement and only holding at the tip of vessel and coagulating while pulling off of the muscle layer, no further delayed perforation occurred. However, in some of those lesions with severe fibrosis due to past piecemeal resections or argon plasma coagulation therapy, we have experienced delayed perforation. Preemptive clip closure of post-ESD defect is recommended if there is any suspicion of injury to the muscularis propria, even without clear evidence of perforation [2]. Furthermore, we have experienced delayed perforation that was most likely caused by the increased intraluminal pressure due to air insufflation (Fig. 19.5). Currently, we use CO2 gas for insufflation for all cases undergoing ESD procedure. This reduces the duration of dead space caused by perforation and accumulation of gas, and also reduces any symptoms associated with rapid resorption of gas (Fig. 19.6).

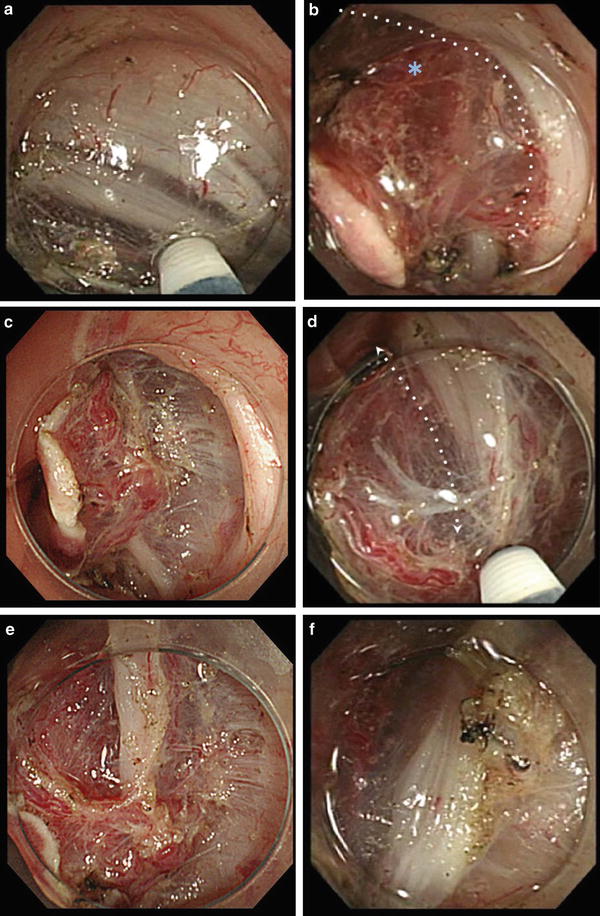

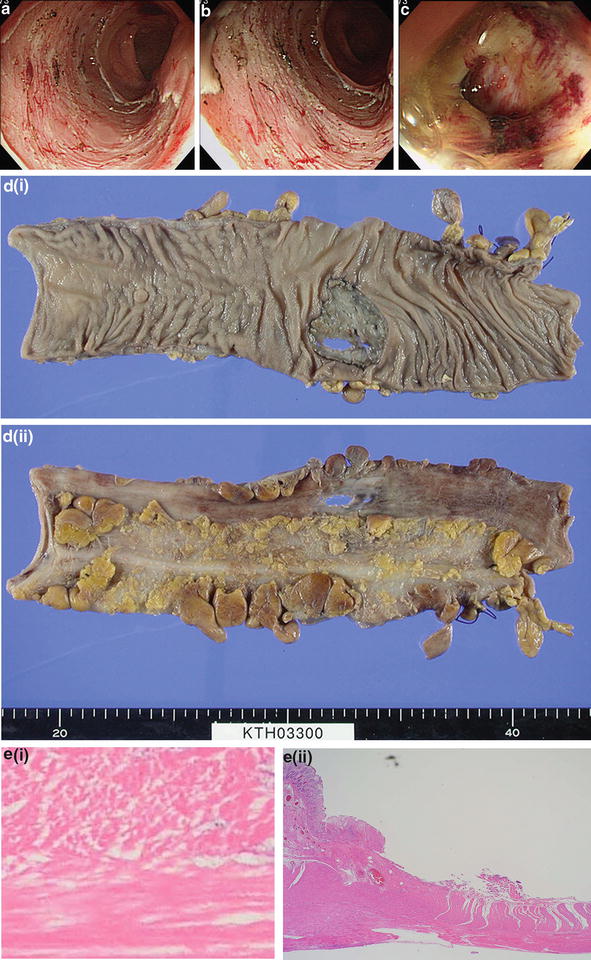

Fig. 19.4

A case of postprocedural perforation of the sigmoid colon. (a) Resection bed after an ESD procedure. (b) Contact coagulation was performed on exposed vessels using the soft coagulation mode on the hot biopsy forceps. (c) On the day following the ESD procedure, pneumoperitoneum was confirmed with a CT after a sudden onset of a abdominal pain. Endoscopy was performed in an attempt to reef the wound. Large, flap-shaped perforation and leakage of opaque intestinal fluid was confirmed. (d) Excised sample. Conservative treatment was deemed extremely risky and an emergency laparotomy was performed. (e) Histopathological image. Widespread coagulation necrosis has extended to the periphery of the dislodged muscularis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree