Site

Author

Year

n

Delayed bleeding (%)

Reference

Stomach

Oda

2005

1,033

6.0

[8]

Kakushima

2006

383

3.4

[9]

Imagawa

2006

159

0

[10]

Onozato

2006

171

7.6

[11]

Oda

2006

303

0

[12]

Hirasaki

2007

112

4.0

[13]

Jung

2007

552

7.6

[14]

Takizawa

2008

1,083

5.8

[15]

Ono

2008

314

8.3

[16]

Takenaka

2008

306

0.7

[17]

Hoteya

2009

572

4.9

[18]

Isomoto

2009

589

1.7

[19]

Chung

2009

1,000

15.6

[20]

Takizawa

2009

1,382

9.7

[21]

Hotta

2010

703

0.3

[22]

Mannen

2010

478

8.9

[23]

Goto

2010

454

5.7

[24]

Tsuji

2010

398

5.8

[25]

Ahn

2011

833

5.3

[26]

Akasaka

2011

1,188

3.1

[27]

Lee

2011

806

4.2

[28]

Higashiyama

2011

924

3.0

[29]

Okada

2011

647

4.3

[30]

Sugimoto

2012

485

3.7

[31]

Goto

2012

1,814

5.5

[32]

Toyokawa

2012

1,123

5.0

[33]

Table 16.2

The rate of delayed bleeding after ESD for esophagus and colorectum

Site | Author | Year | n | Delayed bleeding (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Esophagus | Fujishiro | 2006 | 58 | 0 | [34] |

Kakushima | 2006 | 30 | 0 | [35] | |

Takizawa | 2007 | 87 | 0 | [36] | |

Yoshinaga | 2008 | 25 | 0 | [37] | |

Ishihara | 2008 | 110 | 0 | [38] | |

Ono | 2009 | 107 | 0 | [39] | |

Hirasawa | 2010 | 58 | 5.2 | [40] | |

Ishii | 2010 | 37 | 0 | [41] | |

Repici | 2010 | 20 | 0 | [42] | |

Tanaka | 2012 | 246 | 1.2 | [43] | |

Isomoto | 2013 | 291 | 0.7 | [5] | |

Kanzaki | 2013 | 48 | 2.1 | [44] | |

Colorectum | Fujishiro | 2007 | 200 | 1.0 | [45] |

Saito | 2007 | 200 | 2.0 | [46] | |

Tanaka | 2007 | 70 | 1.4 | [47] | |

Hurlstone | 2007 | 42 | 2.3 | [48] | |

Onozato | 2007 | 35 | 0 | [49] | |

Tamegai | 2007 | 71 | 0 | [50] | |

Toyonaga | 2009 | 468 | 1.5 | [51] | |

Zhou | 2009 | 74 | 1.3 | [52] | |

Isomoto | 2009 | 292 | 0.7 | [53] | |

Yoshida | 2010 | 119 | 1.6 | [54] | |

Saito | 2010 | 1,111 | 1.5 | [4] | |

Hotta | 2012 | 219 | 2.7 | [55] | |

Hotta | 2012 | 146 | 1.4 | [56] | |

Yoshida | 2013 | 530 | 2.3 | [57] |

How to successfully manage bleeding both during and after ESD will be discussed in this chapter.

Preparation

Before starting training of ESD, pre-procedural, theoretic preparation is necessary. An endoscopist who intends to learn ESD must learn not only about the technique of ESD, but also the basic knowledge of bleeding (e.g. risk factors, incidence, management, etc.), as well as apparatuses such as electrosurgical units, endoscopic knives, and various other devices. The physician should also check all information of ESD patient, such as the past medical history and daily medications, especially anticoagulant agents.

The next steps for trainees are to observe expert endoscopists in action as they perform ESD procedures and assist experts performing the procedure, before beginning themselves. By assisting experienced endoscopists, trainees acquire the skills needed to troubleshoot various situations. Moreover, obtaining expertise in hemostasis before starting ESD is highly recommended since most of the difficulties surrounding the procedure are related to uncontrollable hemorrhage [58].

Instruments

An endoscope with a water jet function (GIF-Q260J, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) mounted with a soft transparent hood (TOP Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) is mainly used. This helps facilitate placement of the endoscope, especially during tumor dissection. Normal saline has been used as the injection solution for EMR; however, to achieve better lifting of the lesion in order to lessen the risk of perforation and to lessen tissue damage of the resected specimen, a solution containing sodium hyaluronate has been developed [59]. Many groups now use a commercially available solution of 0.4 % sodium hyaluronate (MucoUp, Johnson & Johnson, Tokyo, Japan). These solutions are usually combined with diluted epinephrine, which is used for the prevention of active bleeding.

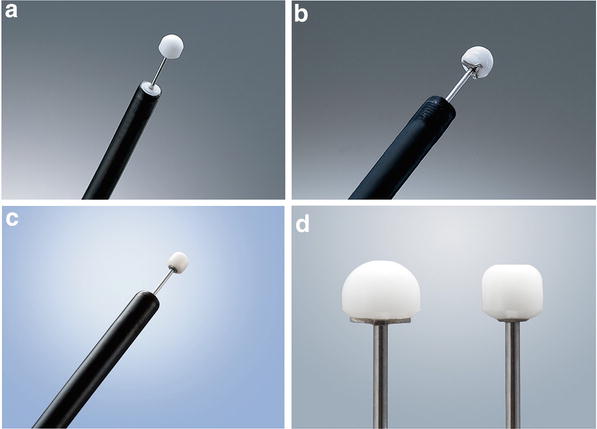

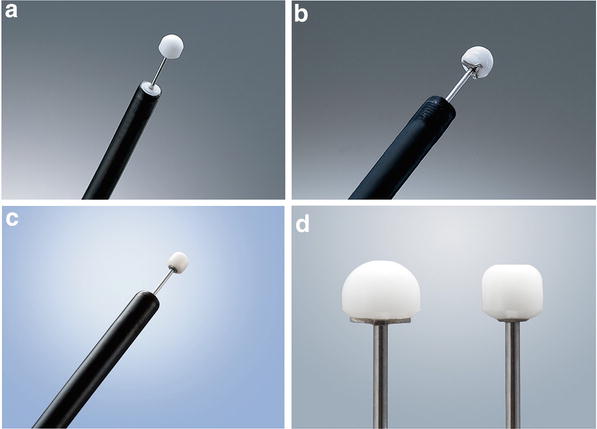

Various knives can be used in ESD. At our institution, we developed IT knife-2 (KD-611L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The difference between the IT knife (KD-610L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and the IT knife-2 is the attachment of a short, three-prong blade between the needle and the ceramic tip (Fig. 16.1a, b). Drawbacks in cutting performance of the IT knife have been remarkably improved with the IT knife-2, such as cutting difficulty while the endoscope is looking downward and the relatively poor performance of cutting in a lateral direction. Consequently, the operating time using the IT knife-2 is reported to be much shorter than that using the original IT knife [16, 36, 60].

Fig. 16.1

IT knife series. (a) Original IT knife (KD-610L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). (b) IT knife 2 (KD-611L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). (c) IT knife nano (KD-612L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). (d) IT knife 2 and IT knife nano

Since the development of IT knife-2 was mainly for application in the stomach, the insulated tip was too large to be used in the esophagus and colon where the submucosal layer is thinner and the lumen is narrower. To solve these issues, the new IT knife nano (KD-612L; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was recently developed, which has a smaller insulated tip (Fig. 16.1c, d). Now, the IT knife-2 is mainly used for gastric ESD, and IT knife nano for esophageal and colonic ESD.

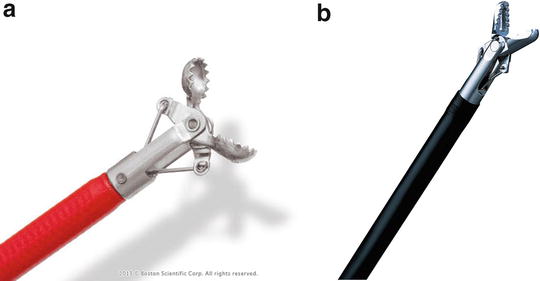

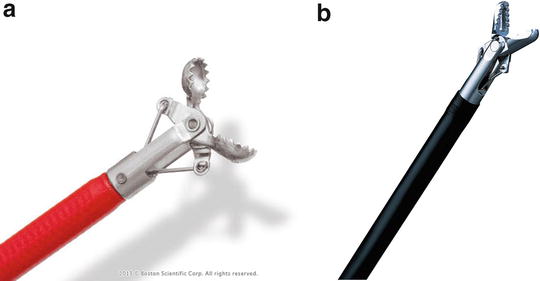

At our institution, the VIO300D (Erbe, Germany) is mainly used as the electrosurgical unit. The instruments and settings are shown in Table 16.3. For hematemesis, we use hot biopsy forceps (Radial jaw, Boston Scientific, Tokyo, Japan) for stomach, and Coagrasper (FD-410LR, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 16.2) for esophagus and colon. In cases of severe bleeding that could not be stopped by coagulation, endoclips were deployed. Because endoclips interfere with the subsequent resection procedure or dissection, one should dissect more submucosal tissue around the bleeding site in order to better expose the bleeding site before clipping.

Table 16.3

Instruments and conditions for ESD

Stomach | Esophagus | Colorectum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Device | VIO300D | Device | VIO300D | Device | VIO300D | |

Marking | APC | Forced APC, 40 W, 1.8 L/min | APC | Precise APC, E3, 1.8 L/min | – | – |

Precut | Needle knife | Dry cut, E 4, 50 W | Needle knife | Dry cut, E3, 30 W | Dual knife | Endocut Q, E3-D2-I2 |

Mucosal incision | IT-2 | Endocut Q, E3-D1-I2 | IT-nano | Endocut Q, E3-D1-I1 | Dual knife | Endocut Q, E3-D2-I2 |

Submucosal dissection | IT-2 | Swift coag, E5, 100 W | IT-nano | Swift coag, E5, 45 W | IT-nano/Dual knife | Swift coag, E3, 40 W |

Minor oozing | IT-2 | Swift coag, E5, 100 W | IT-nano | Swift coag, E5, 45 W | IT-nano/Dual knife | Swift coag, E3, 40 W |

Major bleeding | Hot biopsy | Soft coag, E6, 100 W | Coagrasper | Soft coag, E6, 80 W | Coagrasper | Soft coag, E5, 80 W |

Fig. 16.2

Hemostatic forceps. (a) Hot biopsy forceps (Radial Jaw 4, Boston Scientific, Tokyo, Japan). (b) Coagrasper (FD-410LR, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan)

Bleeding During ESD (Immediate Bleeding)

Bleeding during the procedure is infrequent with EMR techniques, but is quite common and almost unavoidable with ESD. It sometimes requires the procedure to be withheld or aborted; however, with the development of new endoscopic techniques and technology, it now only rarely becomes significant to the extent that requires the procedure to be aborted [8]. Management of immediate bleeding plays a critical role in the successful completion of ESD.

Immediate bleeding was found in 63 of 945 patients (7 %) in a previous report, in which immediate bleeding was defined as the diminution of 2 g/dL in hemoglobin (Hb) between pre-procedure and next-day levels [8]. The rates of significant immediate bleeding in the upper and middle thirds of the stomach are higher than in the lower third (Table 16.4) because of the larger diameter of the submucosal arteries in the upper and middle thirds of the stomach [61].

Table 16.4

Relation between immediate/delayed bleeding and lesion location, size (from Oda et al. [8])

Immediate bleeding | Delayed bleeding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Location | U | 8 % | (14/176) | 1 % | (1/176) |

M | 8 % | (35/431) | 6 % | (27/431) | |

L | 3 % | (14/426)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||