Table 19.1 Grading of clinical evidence in the chemoprevention and chemotherapy of travelers’ diarrhea [80].

| Category | Grade | Definition |

| Strength of evidence | A | Good evidence to support a recommendation for use |

| B | Moderate evidence to support a recommendation for use | |

| C | Poor evidence to support a recommendation | |

| D | Moderate evidence to support a recommendation against use | |

| E | Good evidence to support a recommendation against use | |

| Quality of evidence | I | Evidence from ≥1 properly randomized, controlled trial |

| II | Evidence from ≥1 well-designed clinical trial without randomization, from case-controlled analysis of cohort study | |

| III | Consensus evidence, evidence from one authority or reports of expert committees |

Prevention of travelers’ diarrhea

Given the high risk of acquiring TD and the importance of bacterial enteropathogens it is easy to see why there is such an active interest in preventing the illness through chemo or immune-prophylaxis.

Historical considerations

The first evidence that bacterial enteropathogens were responsible for TD was provided by Kean and colleagues, showing the value of antibiotics in preventing the disease [1]. Prophylactic use of antibiotics during international travel in the 1950s was widely practiced. A study carried out in 1957 demonstrated that more than 35% of persons returning to the USA from Mexico were taking prophylactic antibiotics to prevent diarrhea during their trip [28]. During the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, the British team credited taking multiple doses of oral sulfonamides and oral streptomycin for keeping them well during competition; the American. and Australian teams had higher rates of diarrhea, probably because they relied upon a single daily dose of sulfonamide for protection [29].

Bradley and David Sack from Johns Hopkins then demonstrated the value of doxycycline in preventing TD [30, 31] until resistance to the drug prevented further evaluation [32]. In the 1980s studies were conducted showing the effectiveness of liquid [33] or tablet formulation [34] of bismuth subsalicylate (BSS) in preventing TD. BSS was safely given to the trial participants, with only darkening of stools and tongues from harmless bismuth sulfide, and mild tinnitus, presumably from the absorbed salicylate, as adverse effects. The drug was more effective when it was taken in a total dose of 2.1 g/d in four equally divided doses than when it was taken in a similar daily dose on a twice a day regimen, or in half of this dose four times a day [35].

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was shown to prevent TD in studies carried out in the 1980s [36]. Also, in the 1980s and 1990s, a number of trials established the value of the fluoroquinolones in preventing TD [37–40]. General use of antibiotics for chemoprophylaxis during travel was largely stopped by a Consensus Development Conference held at the National Institutes of Health in 1985 [41], because of concern about adverse effects, and the stimulation of resistance by widespread use of systemically absorbed antibiotics and also because of the difficulty in identifying appropriate recipients of preventive drugs.

The concept became of interest once more with the availability of non-absorbed (<0.4%) rifaximin. This antibacterial preparation had no obvious safety issues, as seen in the clinical trials, and the non-absorbed nature of the drug reduced the concerns about systemic side effects and development of resistance among extra-intestinal bacteria. Rifaximin was shown to be effective in preventing TD in two studies in Mexico, in 2003 [3] and 2005 [42]. A third trial was carried out in Thailand, but the frequency of TD was too low to permit evaluation of the efficacy of the drug (Steffen R, unpublished data).

Immunoprophylaxis

After World War II it was found that rates of diarrhea in people became lower as they lived in high risk areas [43]. This immunity was shown to occur over several months in American students attending classes in Mexico [2]. The natural immunity that developed in these students was associated with reduced rates of ETEC diarrhea [14, 44]. Not surprisingly the first successful TD vaccine was directed toward prevention of ETEC. The first licensed vaccine, developed by the Swedish Biological Laboratories, consisted of a combination of whole cell Vibrio cholerae strains together with a recombinant form of the binding subunit of cholera toxin. The vaccine Dukoral provided short-term protection against ETEC [45] because of the similarity of the binding subunit of cholera toxin with the binding subunit of heat labile enterotoxin (LT) of ETEC. This vaccine was shown to prevent TD [46] and is presently available commercially as an ETEC and cholera vaccine throughout Europe and Canada.

Following studies demonstrated the feasibility of developing a brisk IgG antibody response to transcutaneously administered ETEC LT [47] when a randomized, placebo-controlled trial was carried out in which the antigen or placebo was administered twice by skin patch to approximately 200 adults before travel to Mexico and Guatemala [48]. In this trial, the observed rates of moderate to severe diarrhea were: placebo 21%, LT patch, 5%, p = 0.007. A larger phase III study was planned for 2009.

Effectiveness of chemoprophylaxis and immunoprophylaxis in the prevention of TD

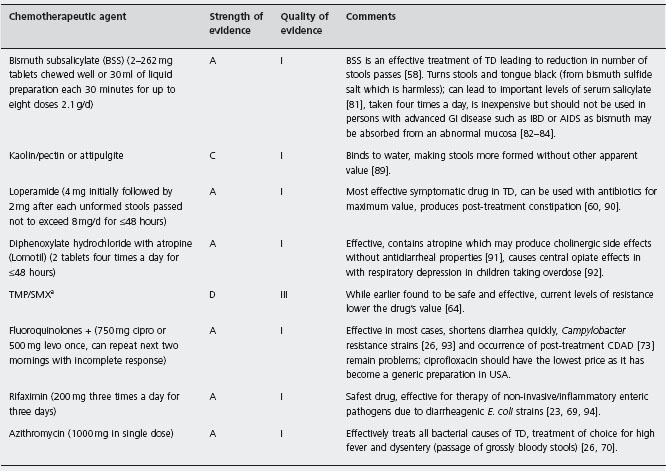

In Table 19.2 the strength of evidence for the various preventive drugs and vaccines is provided. BSS, fluoroquinolones and rifaximin are labeled as A1 to indicate the existence of good evidence for efficacy in preventing TD, with at least one well designed randomized controlled clinical trial having been performed.

Current practice and recommendations

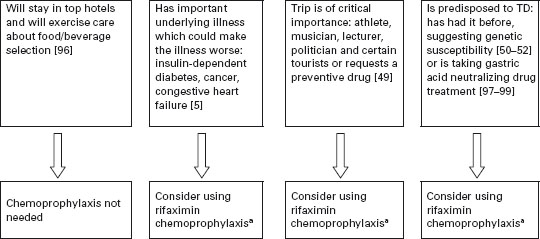

In Figure 19.2, an algorithm is provided that outlines one approach to identifying persons who might be candidates for chemoprophylaxis during high-risk travel. If persons stay in better hotels, eat at hotel restaurants and exercise care on what foods and beverages are consumed, the need to use active prevention methods is lessened. Chemoprophylaxis is appropriate to offer to persons with underlying medical conditions that may be complicated by a diarrheal illness [5, 49], persons for whom an 8–10 hour illness could jeopardize the purpose of an important trip such as athletes during competition, politicians and business travelers with important meetings, musicians and certain tourists with a carefully planned itinerary [49], persons who have experienced a previous bout of TD, suggesting the presence of a genetic susceptibility [50–52], and other travelers who request a preventive medication [49]. The preferred drug is rifaximin used in a dose of one 200mg tablet with the major daily meal(s). Taking two tablets a day with the two major meals is recommended to help deal with compliance concerns [3]. If only one dose a day is taken and it is missed, protection cannot be assured. In the second trial carried out in Mexico, a single dose of 600mg/day was given with the first meal of the day [42]. BSS is a less convenient and slightly less effective alternative to rifaximin.

Table 19.2 Evidence base of chemoprophylaxis in travelers’ diarrhea (preventive drugs are given daily while in high-risk region).

TMP/SMX: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; IBD: infl ammatory bowel disease; AIDS: acquired immune defi ciency syndrome.

The primary objective of chemoprophylaxis is to prevent the disability associated with TD, which averages approximately 24 hours per illness [53, 54]. An unproven benefit of chemoprophylaxis is prevention of the chronic functional bowel syndromes, including IBS secondary to TD, which occur in approximately 10% of persons who experience diarrhea during international travel [55, 56].

Future research in prevention of travelers’ diarrhea

A fundamental question in the prevention of TD remains. Can careful attention to food and beverage intake, focusing on consumption of only the safest items, lower the risk of TD? This is largely an unstudied area that needs innovative research approaches. A second question is: does rifaximin taken for chemoprophylaxis during high-risk travel prevent infection and diarrhea caused by invasive bacteria including Campylobacter, Shigella and Salmonella? Rifaximin prevented shigellosis and Shigella dysentery when adult volunteers were challenged with a virulent strain of Shigella [57]. Preventing invasive forms of TD should be a far easier task than treating an invasive enteric infection once the organisms have extensively penetrated the mucosa. The third question concerning prevention is whether chemoprophylaxis prevents the occurrence of post-infectious IBS. With the frequency of occurrence approaching 10% of TD cases, prevention of IBS should be studied in future clinical trials.

a200mg once or twice a day with major meals or 600mg in a single dose with the first daily meal while out of town; alternative drug bismuth subsalicylate 2-262mg tablets with meals and at bedtime (eight tablets/d or 2.1 g/d).

Treatment of travelers’ diarrhea

Symptomatic therapy

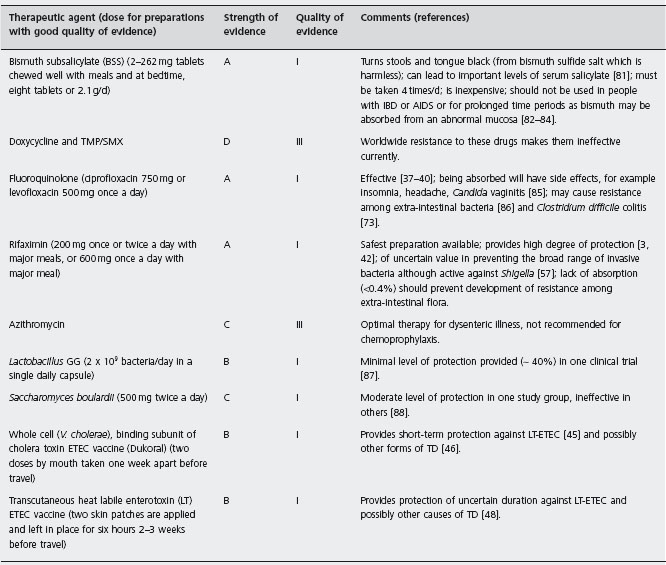

Drugs in this class are designed to reduce the number of unformed stools passed, allowing the traveler to better cope with illness symptoms. The drugs are not designed to cure this form of bacterial infection, and in many treated people the symptoms will continue, although improved, until antibacterial therapy is given. The first drug shown to have value in treatment of TD is bismuth subsalicylate (BSS) [58], which reduced the number of stools passed by 50% compared with placebo treatment. BSS exerts its anti-diarrheal effect through the drug’s salicylate moiety [59]. Loperamide was more effective than BSS in a randomized controlled trial, reducing the number of stools passed in TD by 60% [60]. Loperamide decreases diarrhea by slowing the intraluminal column, giving more opportunity for the gut to absorb water and electrolytes [61]. The drug also has direct antisecretory effects [62].

Antimicrobial therapy

Antimicrobial therapy is the mainstay of treatment of TD and is aimed at illness cure. Symptomatic treatments characteristically require rescue medication with antibacterial therapy to stop diarrhea [60, 63]. Trimethoprim/sulfame-thoxazole was the first antibiotic shown to effectively reduce the duration of diarrhea. When TMP/SMX resistance became widespread [64] other drugs were evaluated. The fluoroquinolones were found to be highly active in treating TD [23, 65–68]. Rifaximin, a poorly absorbed (<0.4%) antibacterial drug has been shown to be as effective as fluoroquinolones for overall TD [23, 69], while the drug is less effective against invasive pathogens as a group [23]. Azithromycin has been shown to effectively treat TD due to non-invasive [70] and invasive [26, 71] pathogens. The fluoroquinolones have adverse effects, including Achilles tendon rupture [72], for which a “black box warning” has been issued by the US FDA, and the occurrence of Clostridium difficile infection [73] due to near depletion of colonic flora caused by this class of drugs [37]. Azithromycin in the dose recommended commonly causes nausea [26]. The safest antibiotic treatment appears to be rifaximin, which has been as safe as the placebo control in each one of the clinical trials so far conducted.

Combination therapy

Where loperamide has rapid onset of action and effectively controls the number of stools passed, antibiotics have slow onset of action but are employed to cure the infection and stop the diarrhea. The drugs can be given together, obtaining additive benefits [63, 74, 75].

Evidence-based review of travelers’ diarrhea treatment

All persons planning trips to developing regions should arm themselves with antidiarrheal drugs to employ if they develop diarrhea (see Table 19.3). The drugs for which there is strong and quality evidence to support their use in the treatment of TD include BSS, loperamide, fluoroquinolones, rifaximin and azithromcyin.

atrimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; + ciprofloxacin (cipro), levofloxacin (levo); CDAD: Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea.

Current practice and recommendations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree