Fig. 21.1

Relationship of pelvic structures to presacral space

This space extends superiorly to the peritoneal reflection and inferiorly to the rectosacral fascia and the supralevator space.

Laterally, the area is bordered by the ureters, the iliac vessels, and the sacral nerve roots (Fig. 21.2a).

Fig. 21.2

(a) Anterior view of pelvic anatomy. (b) Posterior view or pelvic anatomy with sacral elements removed

Several important vascular and neural structures are located in this area and injury to them may have important physiologic rectoanal sequelae as well as neurologic and musculoskeletal consequences.

If all sacral roots on one side of the sacrum are sacrificed, the patient will continue to have normal anorectal function.

Likewise, if the upper three sacral nerve roots are left intact on either side of the sacrum, the patient’s ability to spontaneously defecate and to control anorectal contents will remain essentially intact.

If, however, both S-3 nerve roots are sacrificed, the external anal sphincter will no longer contract in response to gradual balloon dilation of the rectum, and this will translate clinically into variable degrees of anorectal incontinence and difficult defecation.

If sacrectomy is to be performed, the surgeon must be familiar with the relationship among the thecal sac, sacral nerve roots, sciatic nerve, piriformis muscle thecal sac, and sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments (Fig. 21.2b).

Structurally, the majority of the sacrum can be resected; if more than half of the S-1 vertebral body remains intact, pelvic stability will be maintained.

However, preoperative radiation to the sacrum may ultimately lead to stress fractures if only S-1 remains. As such, spinopelvic stability may be augmented with fusion in select patients.

Knowledge of anatomy of the thigh and lower extremity is also required in complex cases requiring muscle or other soft tissue flaps. It is important to discuss with patients preoperatively the potential neuromuscular and visceral losses that may occur during the operation and how this will influence their function and quality of life.

Classification

General Considerations

Presacral lesions are rare. Reports from various large referral centers have indicated that their incidence may be as low as 1 in 40,000 hospital admissions (0.014 %).

Lesions found in the presacral space can be broadly classified as congenital or acquired and benign or malignant. Two-thirds of lesions are congenital, two-thirds of which are benign and one-third neoplastic.

As this area contains totipotential cells that differentiate into three germ cell layers, a multitude of tumor types may be encountered.

The classification first described by Uhlig and Johnson has been used for many years and divides tumors into broad categories; congenital, neurogenic, osseous, and miscellaneous. We have modified and updated this system to subcategorize tumors into malignant and benign entities, as this greatly impacts therapeutic approaches (Table 21.1 ).

Table 21.1

Classification of presacral tumors

Congenital

Benign

Developmental cysts (teratoma, epidermoid, dermoid, mucus secreting)

Duplication of the rectum

Anterior sacral meningocele

Adrenal rest tumor

Malignant

Chordoma

Teratocarcinoma

Neurogenic

Benign

Neurofibroma

Neurilemmoma (schwannoma)

Ganglioneuroma

Malignant

Neuroblastoma

Ganglioneuroblastoma

Ependymoma

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (malignant schwannoma, neurofibrosarcoma, neurogenic sarcoma)

Osseous

Benign

Giant-cell tumor

Osteoblastoma

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Malignant

Osteogenic sarcoma

Ewing’s sarcoma

Myeloma

Chondrosarcoma

Miscellaneous

Benign

Lipoma

Fibroma

Leiomyoma

Hemangioma

Endothelioma

Desmoid (locally aggressive)

Malignant

Liposarcoma

Fibrosarcoma/malignant fibrous histiocytoma

Leiomyosarcoma

Hemangiopericytoma

Metastatic carcinoma

Other

Ectopic kidney

Hematoma

Abscess

Gross and Histologic Appearance

Epidermoid cysts result from defects during the closure of the ectodermal tube. They are histologically composed of stratified squamous cells, do not contain skin appendages, and are typically benign.

Dermoid cysts also arise from the ectoderm, but histologically they contain stratified squamous cells and skin appendages. These are also generally benign.

Epidermoid and dermoid cysts tend to be well circumscribed and round and have a thin outer layer. Occasionally, they communicate with the skin surface producing a characteristic postanal dimple. They are most common in females and the infection rate may be high as they are often misdiagnosed as a perirectal abscess and operatively manipulated.

Enterogenous cysts are lesions thought to originate from sequestration of the developing hindgut; if related with the rectum, they are called rectal duplication cysts. Because they originate from endodermal tissue, they can be lined with squamous, cuboidal, or columnar epithelium. Transitional epithelium may also be found. These lesions tend to be multilobular with one dominant lesion and smaller satellite cysts. Like dermoid and epidermoid cysts, they can become infected and are more common in women. These are generally benign, but case reports have described malignant transformation within rectal duplications.

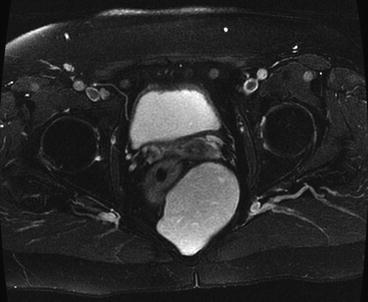

Tailgut cysts, which are sometimes referred to as cystic hamartomas, are congenital lesions arising from remnants of normally regressing postanal primitive gut. They are more common in females and can be seen as multiloculated or biloculated cysts on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 21.3). These cysts are composed of squamous, columnar, or transitional epithelium that may have a morphologic appearance similar to that of the adult or fetal intestinal tract. The presence of glandular or transitional epithelium differentiates this lesion from an epidermoid or dermoid cyst. Malignant transformation has been reported in up to 13 % in some series.

Fig. 21.3

Tailgut cyst

Teratomas are true neoplasms derived from totipotential cells and include all three germ cell layers. They may undergo malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma arising from the ectodermal tissue or rhabdomyosarcoma arising from the mesenchymal cells. Anaplastic tumors are also seen in which the tissue of origin may not be distinguishable. Histologically, these tumors are referred to as either “mature” or “immature” reflecting the degree of cellular differentiation. Teratomas are more common in females and in the pediatric age group and are often associated with other anomalies of the vertebra, urinary tract, or anorectum. In adults, malignant degeneration can occur in 40–50 %. Incomplete or intralesional resection increases the likelihood of malignant degeneration. These lesions can also become infected and be misdiagnosed as a perirectal abscess or fistula. Diagnosis is often delayed and these tumors may reach considerable size.

Sacrococcygeal chordoma is the most common malignancy in the presacral space. These tumors are believed to originate from the primitive notochord which embryologically extends from the base of the occiput to the caudal limit in the embryo. They have a predilection for the pheno-occipital region at the base of the skull and for the sacrococcygeal region in the pelvis (Fig. 21.4). They predominate in men and are rarely encountered in patients younger than 30 years of age. These tumors may be soft, gelatinous, or firm and may invade, distend, or destroy bone and soft tissue. Hemorrhage and necrosis within tumors may lead to secondary calcification and pseudocapsule formation. Common symptoms include pelvic, buttock, and lower back pain aggravated by sitting and alleviated by standing or walking. Diagnosis is often delayed and these tumors may reach a considerable size. Although chordomas are low- to intermediate-grade malignant lesions, a radical surgical approach that achieves negative margins greatly improves survival.

Fig. 21.4

Distribution of chordomas (Mayo Clinic orthopedic database)

Anterior sacral meningoceles are a result of a defect in the thecal sac and may be seen in combination with presacral cysts or lipomas. Typical symptoms include constipation, low back pain, and headache exacerbated by straining or coughing. Anterior sacral meningocele may be associated with other congenital anomalies, such as spina bifida, tethered spinal cord, uterine and vaginal duplication, or urinary tract or anal malformations. Surgical management consists of ligation of the dural defect.

Neurogenic tumors include neurilemmomas, ganglioneuromas, ganglioneuroblastomas, neurofibromas, neuroblastomas, ependymomas, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (neurofibrosarcoma, malignant schwannomas, and neurogenic sarcomas). In a Mayo Clinic series, schwannomas were the most common benign tumor and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors the most common malignant lesions. Although neurogenic tumors tend to slowly grow, they may eventually reach considerable size. Preoperative differentiation between benign and malignant pathology can be difficult without a tissue biopsy but is of paramount importance to guide the operative approach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree