Chapter 23 Premenstrual Syndrome and Menstrual-Related Disorders

INTRODUCTION

The literature on PMS has focused almost entirely on women with adverse premenstrual experiences. Some women experience well-defined medical conditions, such as migraine, epilepsy, irritable bowel syndrome, and asthma, that are linked to, and exacerbated by, the hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle. However, there is evidence that 5% to 15% of women may experience positive changes in the premenstruum.1 Clinicians now understand the need to discriminate between the usual premenstrual experience of ovulatory women (wherein premenstrual molimina forewarn of impending menstruation) and PMS. This chapter reviews our current understanding of menstrual-related conditions, including PMS.

DEFINITION AND PREVALENCE

Molimina

Molimina are symptoms, such as breast pain, swelling, bloating, acne, and constipation, that foreshadow impending menstruation. Some or all of these symptoms are estimated to occur in 80% to 90% of women of reproductive age. Approximately 30% to 40% of women report these symptoms to be distressing enough that they would seek a remedy if one were available. Swelling of the extremities and abdominal bloating are molimina reported by 60% of women, although objective documentation of weight gain is usually lacking.2,3 Cyclic breast symptoms affect 70% of women, with 22% reporting moderate to extreme discomfort.4

Premenstrual Syndrome

Premenstrual syndrome is defined as the cyclic recurrence in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle of a combination of distressing physical, psychological, and/or behavioral changes of sufficient severity to result in deterioration of interpersonal relationships and/or interference with normal activities.5 This definition emphasizes the fact that a diagnosis of PMS should rely not only on the presence of typical premenstrual symptoms, but also on a level of severity enough to disrupt normal function. The term PMS should be reserved for a more severe constellation of symptoms, mostly psychiatric, that leads to major interference with day-to-day activities and interpersonal relationships.6 Women with this degree of symptoms probably comprise 3% to 5% of women in their reproductive years.7–10

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

In the psychiatric literature, the term premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is used to indicate the most serious premenstrual disturbances that are associated with deterioration in functioning. PMDD is characterized by depressed or labile mood, anxiety, irritability, anger, and other symptoms occurring exclusively during the 2 weeks preceding menses. According to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV), the symptoms must be severe enough to interfere with occupational and social functioning (Table 23-1).11 This sets PMDD apart from the more common PMS, as a severely distressing and disabling condition that requires treatment.

Table 23-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)

| 1. Timing of symptoms |

| Symptoms are present during the last week of the luteal phase, remit within the first few days of menses, and are absent during the week following menses. The symptoms occur during most, if not all, menstrual cycles. |

| 2. Symptoms |

| At least five symptoms are required, including at least one of the first four symptoms: |

| 3. Severity |

| The symptoms markedly interfere with work, school, social activities, and relationships with others. |

| 4. Other disorders |

| Rule out that the disorder is not merely an exacerbation of a major affective, panic dysthymic, or personality disorder, although PMDD can be superimposed on any of these disorders. |

| 5. Confirmation of the disorder |

| The above criteria must be confirmed by prospective daily self-rating for two consecutive menstrual cycles. |

Adapted from: American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, D.C. APA, 1994.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

PMS-like behavior has been reported both in humans and in nonhuman primates that demonstrate menstrual cyclicity. In the nonhuman primate, zoologists have noted premenstrual changes in behavior and appetite similar to those reported by women with PMS.12,13 The availability of effective contraception since midway through the twentieth century has meant that repeated cycles of pregnancy and lactation were no longer the biological destiny of women in the developed world—and as a direct result the expected number of menstrual cycles in a woman’s lifetime increased from as few as 50 to as many as 500, with a commensurate increase in menstrual cycle-related disorders.

Little is known about the inheritance of PMS. However, there is support for a genetic predisposition. Surveys have found that as many as 70% of daughters of affected mothers were themselves PMS sufferers, whereas 63% of daughters of unaffected mothers were symptom-free.14

Premenstrual syndrome disappears during suppression of the ovarian cycle; for example, during hypothalamic amenorrhea due to excessive physical, or nutritional stress, during lactational amenorrhea, during pregnancy, and after menopause—either natural or induced.15,16 Interestingly, hormone therapy employing sequential progestin sometimes triggers PMS symptoms in susceptible women, whereas continuous combination hormone replacement therapy is not associated with these changes.17,18

DIAGNOSIS

History

Caution is needed in immediately accepting such a typical history as diagnostic of PMS. Researchers have found that many psychiatric conditions worsen premenstrually, a situation referred to as premenstrual magnification. Hence, an individual with an underlying psychiatric disorder may recall and relate the symptoms that were most severe in the premenstrual week, while ignoring the lower level of symptoms that exist throughout the month.19

Prospective Symptom Record

The clinician can have confidence in the diagnosis only by obtaining a prospective symptom record over a 1- to 2-month period. Any calendar used for this purpose must obtain information on four key areas: symptoms, severity, timing in relation to the menstrual cycle, and baseline level of symptoms in the follicular phase (Table 23-2). Information should be sought about stresses related to the woman’s occupation and family life, because these may tend to exacerbate PMS. Past medical and psychiatric diagnoses may be relevant in that a variety of medical and psychiatric disorders may show premenstrual exacerbation.

Table 23-2 Key Elements of a Prospective Symptom Record Used for the Diagnosis of PMS

| 1. | Daily listing of symptoms |

| 2. | Ratings of symptom severity throughout the month |

| 3. | Timing of symptoms in relation to menstruation |

| 4. | Rating of baseline symptom severity during the follicular phase |

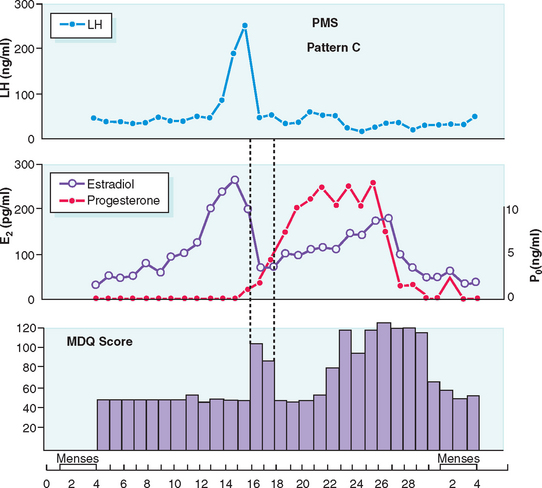

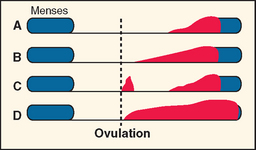

Typically PMS symptoms appear after ovulation and worsen progressively leading up to menstruation. Approximately 5% to 10% of PMS sufferers experience a brief burst of typical PMS symptoms coincident with the midcycle fall in estradiol that accompanies ovulation20 (Fig. 23-1). PMS symptoms resolve at varying rates after onset of menstruation. In some women there is almost immediate relief from psychiatric symptoms with the onset of bleeding; for others the return to normal is more gradual. The most severely affected women report symptoms onset shortly after ovulation (2 weeks before menstruation), resolving at the end of menstruation. Such individuals typically report having only one “good week” per month (Fig. 23-2).21 If this pattern is longstanding it becomes harder and harder for interpersonal relationships to rebound during the good week, with the result that their condition may start to take on the appearance of a chronic mood disorder. Whenever charting leaves the diagnosis in doubt, a 3-month trial of medical ovarian suppression will usually provide a definitive answer.

(From Reid RL: Premenstrual syndrome. In DeGroot L (ed). Endotext.com. Available at: www.endotext.org. Accessed 20 December 2004.)

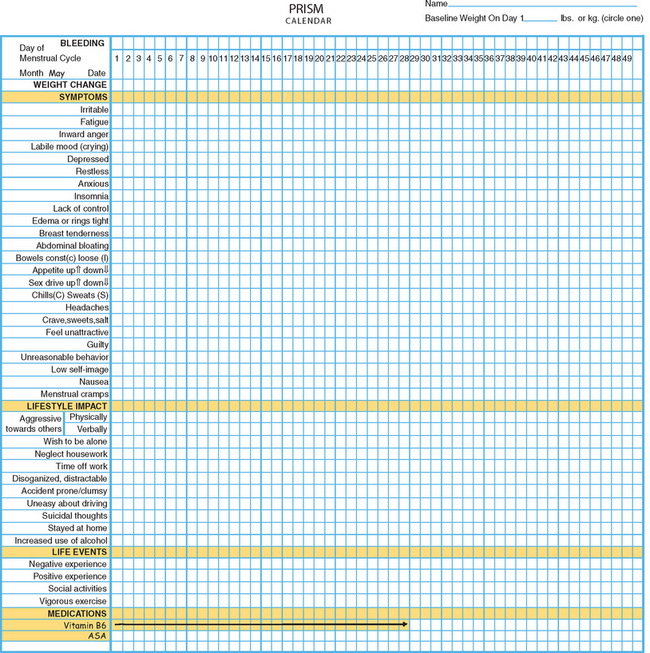

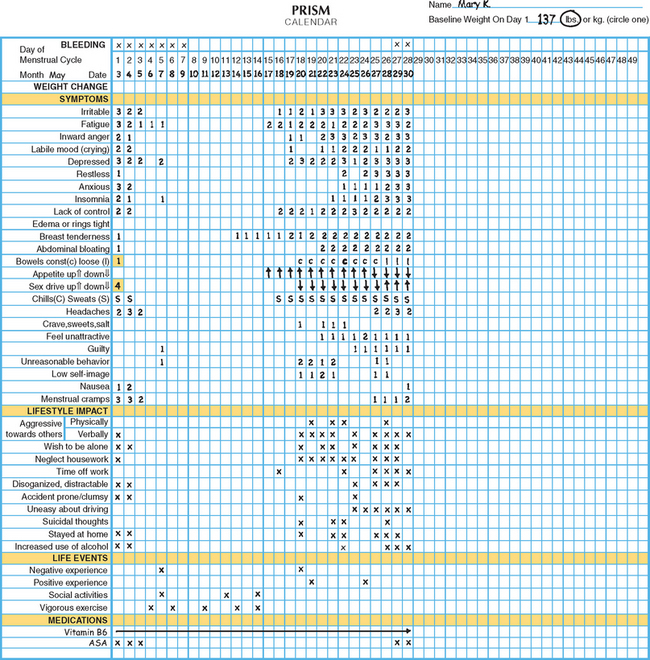

One example of a symptom calendar is the Prospective Record of the Impact and Severity of Menstrual symptoms (PRISM) calendar (Figs. 23-3 and 23-4).5 This instrument allows rapid visual confirmation of the nature, timing, and severity of menstrual cycle-related symptomatology and at the same time provides information on life stressors and current use of PMS therapies.

Figure 23-4 Visual inspection of a completed PRISM calendar reveals a pattern of symptoms consistent with PMS.

Positive premenstrual changes associated with enhanced mood or performance are reported by up to 15% of women. Increased energy, excitement, and well-being have been associated with increased activity, heightened sexuality, and improved performance on certain types of tasks during the premenstrual phase.1

Physical Examination

Organic causes of PMS-like symptoms must be ruled out. Marked fatigue may result from anemia, leukemia, hypothyroidism, or diuretic-induced potassium deficiency. Headaches may be due to intracranial lesions. Women attending PMS clinics have been found to have brain tumors, anemia, leukemia, thyroid dysfunction, gastrointestinal disorders, pelvic tumors including endometriosis, and other recurrent premenstrual phenomena, such as arthritis, asthma, epilepsy, and pneumothorax.16

ETIOLOGY

Since the 1950s a wide range of etiologic theories have been advanced to explain the varied manifestations of PMS. PMS has been attributed to altered levels or ratios of estrogen and progesterone, androgen excess, fluid retention, endogenous hormone allergy, vitamin and trace element deficiencies, prolactin excess, hypoglycemia, bacterial and yeast infections, thyroid dysfunction, endogenous opiate addiction and withdrawal, abnormal metabolism of essential fatty acids leading to prostaglandin E1 deficiency, and altered calcium metabolism, to mention a few.15

As with other areas of confusion and uncertainty, the area of PMS is an attractive one for those promoting unorthodox treatments for personal gain. Many of the theories that underlie such interventions lack biologic plausibility and appear to have emerged as a means to market specific therapeutic products. Conscientious investigators have expended much effort to rigorously evaluate the promotional claims of others. Randomized, controlled trials have failed to confirm the efficacy of most of these purported treatments.

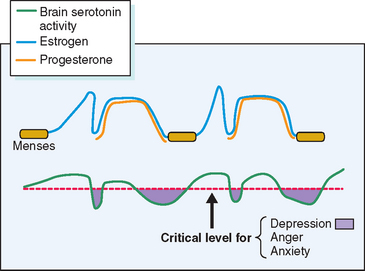

Other theories, while having some biologic plausibility, have not or cannot be confirmed with available diagnostic techniques. No one theory has gained universal acceptance, although consensus is developing that in some susceptible women normal swings in gonadal hormones22 appear to mediate changes in the activity of central neurotransmitters such as serotonin, which in turn incite profound changes in mood and behavior.23 Others have speculated a role for steroid-induced modulation of γ-aminobutyric acid receptors in the brain.24 Although it is likely that many of the physical symptoms (breast tenderness, bloating, constipation) are the direct effect of gonadal steroids, it is intriguing that treatment of PMS with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) will ameliorate the severity of not only psychological, but also physical complaints.25

Several lines of evidence from clinical medicine support this interrelationship between estrogen or lack of estrogen effect (perhaps mediated by progestin-induced depletion of estrogen receptors) and central serotonergic activity.23 Estrogen has been shown to alleviate clinical depression in hypoestrogenic women in double-blind clinical trials.26,27 The addition of sequential progestin therapy to estrogen replacement triggers characteristic PMS-like mood disturbance in some susceptible postmenopausal women.17 Anti-estrogens given for ovulation induction may, at times, provoke profound mood disruption. Women with PMS show a surprisingly high frequency of premenstrual and menstrual hot flashes (85% of PMS sufferers vs. 15% of non-PMS controls) that are typical of those experienced by menopausal women.28,29 SSRIs have been shown to relieve hot flashes in breast cancer survivors made menopausal by chemotherapy.30 In each of these circumstances a decrease in exposure to estrogen has been linked to mood disturbance and in each case a decrease in serotonin activity (inferred from the response to SSRIs) appears to be the proximate cause (Fig. 23-5).

THERAPY

Lifestyle Modification Strategies

Diet

There is a paucity of evidence to support a dietary approach to the control of PMS,31 although there are a few simple dietary measures that may afford a measure of relief for the afflicted woman. Most women with PMS, despite feelings of bloating and tension, show no absolute increase in weight, no change in girth, and no signs of peripheral edema.3 PMS sufferers commonly report cravings for salty and sweet foods, and these dietary alterations may account for unusual cases of premenstrual edema.32 Sudden shifts from low-sodium, low-carbohydrate intake to a diet high in these constituents can account for weight gain of as much as 5 kg in 24 hours.33 For this reason reduction in the intake of salt and refined carbohydrates may help prevent edema and swelling in occasional women with this manifestation of PMS.

Although a link between methylxanthine intake and premenstrual breast pain has been suggested, available data are not convincing.34,35 Nevertheless, a reduction in the intake of caffeine may prove useful in women in whom tension, anxiety, and insomnia predominate.

Several lines of evidence indicate that there is a tendency to increased alcohol intake premenstrually,36 and women should be cautioned that excessive use of alcohol is frequently an antecedent factor in marital discord. Anecdotal evidence suggests that small, more frequent meals may occasionally alleviate mood swings. Based on recent evidence that cellular uptake of glucose may be impaired premenstrually, there is at least some theoretical basis for this dietary recommendation.37 Carbohydrates may exhibit mood-altering effects through a number of mechanisms,38 yet attempts to improve premenstrual symptoms through dietary supplements have not been successful.39,40 Calcium supplementation has been shown to be marginally superior to placebo in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial.41

Exercise

Regular aerobic exercise may relieve PMS symptoms, at least temporarily, in many women,42,43 and it should be recommended as part of an overall program of lifestyle modification. Some women with PMS report that exercise is an outlet for the inward anger and aggression that characterizes their symptomatology.

Medical Interventions

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Mefenamic acid (500 mg three times daily) in the premenstrual and menstrual weeks has outperformed placebo for the treatment of PMS in some but not all clinical trials.44,45 Mefenamic acid is contraindicated in women with known sensitivity to aspirin or those at risk for peptic ulcers.

Oral Contraceptives

The first systematic studies to examine the effects of oral contraceptives on PMS did not find differences in PMS symptoms between oral contraceptive users and nonusers, nor were there significant differences between agents with differing progestational potencies.46,47 Monophasic and triphasic preparations showed similar rates of symptomatology.48

A new oral contraceptive preparation containing a novel progestin with diuretic effects (drospirenone) has undergone the most rigorous testing in normal women and women with strictly defined PMDD. The dosage of progestin in each pill is said to be the equivalent to 25mg of spironolactone. Alhough the evidence supporting a role for fluid retention as an etiologic component of PMS is lacking,3 many women are distressed by feelings of bloating and edema. In controlled clinical trials this new oral contraceptive has been shown to offer relief to some physical and some psychological manifestations of PMS with an improvement in health-related quality of life.49,50

Pyridoxine

Published data in regard to the efficacy of pyridoxine (vitamin B6) have been contradictory51; however, this medication in proper dosages (100 mg daily) is, at worst, a safe placebo that becomes one part of an overall management plan for women with distressing molimina that should include lifestyle modification and changes in diet. Patients should be cautioned that these medications do not work for all women and that increasing the dose of pyridoxine in an effort to achieve complete relief of symptoms may lead to peripheral neuropathy. Pyridoxine should be discontinued if there is evidence of tingling or numbness of the extremities.

Diuretics

The routine use of diuretics in the treatment of PMS should be abandoned. Most women show only random weight fluctuations during the menstrual cycle despite the common sensation of bloating. Spironolactone has been reported to alleviate symptoms in some PMS sufferers.52

Anxiolytics

Some women report overriding symptoms of anxiety and tension or insomnia in the premenstrual week.53 New short-acting anxiolytics or hypnotics such as alprazolam (0.25mg twice daily) or triazolam (0.25mg at bedtime), respectively, may be prescribed sparingly for such individuals.54,55 Buspirone has also proven useful for anxiety and may be particularly helpful in circumstances where SSRIs evoke sexual dysfunction.56

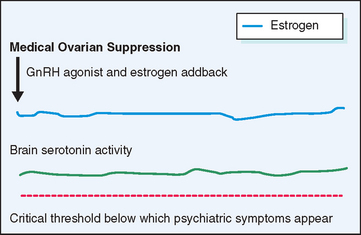

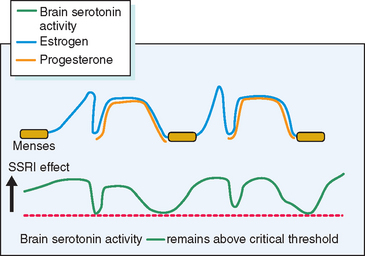

Antidepressant Therapy

A range of newer antidepressant medications that augment central serotonin activity have been shown to alleviate severe PMS.57,58 Because these agents will also relieve endogenous depression, a pretreatment diagnosis achieved by prospective charting is very important. For patients in whom psychiatric symptoms predominate, antidepressant therapy may provide excellent results (Fig. 23-6). SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, and velafaxine (a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), have all been successfully employed.

Figure 23-6 Hypothetical depiction of how drugs that elevate serotonin activity can alleviate PMS.

(From Reid RL: Premenstrual syndrome. In DeGroot L (ed). Endotext.com. Available at: www.endotext.org. Accessed 1 January 2005.)

Most PMS sufferers would prefer to medicate themselves only during the symptomatic phase of the menstrual cycle. Recent studies have demonstrated that luteal phase therapy may be effective for many women with PMS.59 Practically speaking, a trial of SSRI therapy should be commenced with continuous use. After a woman has determined the optimal response that can be achieved with continuous therapy, it is reasonable for her to try luteal phase-only therapy to determine if the benefit is maintained.

Unfortunately, several follow-up studies have demonstrated the rapid recurrence of severe PMS attended by significant social disruption after cessation of therapy with SSRIs.60,61 Practically speaking this would mean that if this line of therapy is chosen extended treatment may be required.

Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists

A different approach to the management of severe PMS has been to suppress the ovarian cycle, which is thought to incite the changes in central neurotransmitters that underlie the manifestations of PMS (Fig. 23-7). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists effect rapid medical ovarian suppression, thereby inducing a pseudomenopause and affording relief from PMS.62 This approach is unsatisfactory in the long term not only because of the troublesome menopausal symptoms it evokes, but also because it creates an increased risk for osteoporosis and possibly ischemic heart disease. When combined with hormone replacement therapy GnRH agonists afford excellent relief from premenstrual symptoms without the attendant risks and symptoms resulting from premature menopause. The major drawback to this therapeutic approach is the expense of medication and the need for the patient to take multiple medications on a long-term basis.

Medical Management of Specific Symptoms

Premenstrual Mastalgia

Premenstrual mastalgia, which affects up to 70% of women in reproductive age, may occur in isolation from other PMS symptoms and, as such, should be considered a moliminal symptom. Low doses of danazol, the synthetic analog of ethinyltestosterone, can bring about dramatic relief of mastalgia in most women.66 This medication is given at a dose of 100mg daily for several cycles followed by maintenance doses of 50mg daily in the luteal phase only. Higher doses of danazol (400mg daily) may be required to relieve other PMS symptoms.67 Mastalgia may also respond to tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, at a dose of 10mg daily.68 Diuretics, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and pyridoxine have not been shown to help mastalgia.

Surgical Therapy

Medical approaches to PMS should be exhausted before consideration of surgery (hysterectomy and oophorectomy) for debilitating PMS. Observational trials have shown this therapy to be effective.69,70 For the woman in whom there is unequivocal documentation that premenstrual symptoms are severe and disruptive to lifestyle and relationships and in whom conservative medical therapies have failed (either due to lack of response, intolerable side effects, or prohibitive cost), the effect of medical ovarian suppression should be tested. At times this therapy (a GnRH agonist and continuous combination hormone replacement therapy) can be maintained until menopause with satisfactory symptom control. Some women, despite complete relief of symptoms, cannot afford to or choose not to take this combination of medications for prolonged intervals (as long as 10 to 15 years from diagnosis until menopause in some cases).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree