Peritoneal/Retroperitoneal Anatomy: Relevance to Performance of Interventional Procedures

INTRODUCTION

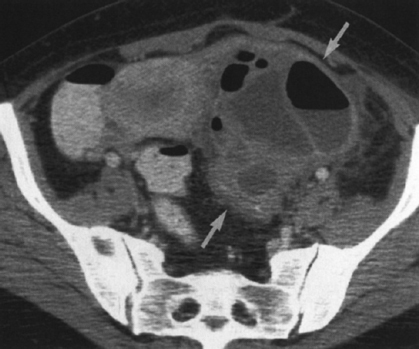

Understanding the compartmental anatomy of the abdomen is of profound importance to the proper performance of percutaneous interventional procedures. It is necessary to understand the peritoneal and retroperitoneal anatomy of the abdomen to prepare for guidance of interventional therapy and to avoid potential pitfalls. For instance, when performing aspiration or drainage of pelvic fluid collection, it is necessary to know compartmental anatomy to understand the possible origins of fluid collections. A pelvic fluid collection may be secondary to a number of conditions including such primary pelvic diseases as a tubo-ovarian abscess; however, the pelvic fluid collection may have spread to the pelvis from another site. As there is free communication from both the right and left pericolic gutter to the pelvic cul-de-sac, the fluid collection may be secondary to an appendiceal or diverticular abscess (Fig. 5–1). Drainage of the pelvic abscess is unlikely to be curative if the primary abnormality, the appendiceal or diverticular abscess, is overlooked.

As another example, placement of abscess drainage catheters from one abdominal or retroperitoneal compartment to another should be avoided at certain times. Often the most direct route for drainage of a subdiaphragmatic abscess may be through the pleura into the subdiaphragmatic space. However, this route should be avoided to prevent the spread of infection to the pleural cavity. Knowledge of the anatomical relationship of the pleural space to the subdiaphragmatic space is needed to avoid this pitfall. This chapter will review the compartmental anatomy of the abdomen and pelvis needed to best perform percutaneous interventional procedures. The chapter will also cover paths of fluid spread and compartmental localization of abdominal abscesses. Potential pitfalls to avoid in performing percutaneous drainage of abdominal pelvic fluid collections will be presented. Complete knowledge of abdominal compartmental anatomy should be obtained by any clinician planning to perform percutaneous interventional procedures.

SUPRADIAPHRAGMATIC VS.SUBDIAPHRAGMATIC FLUID COLLECTION

Although it may seem elementary to determine if fluid is in the pleural cavity or the abdomen, at times this distinction is difficult. Knowledge of fluid location is important when performing any drainage procedure to determine the specific path for needle or catheter placement. Four values (1–4) are used to describe the location of fluid relative to the diaphragm.1–4 These values are assigned as follows:

Figure 5–2 Bare area of the liver. Contrast-enhanced computed tomogram in a 65-year-old man with cirrhosis, ascites (A), and varices shows the thin layer of fat (arrow) between the bare area of the liver and the diaphragm.

- “Bare area” sign. There is a bare area of the liver bounded by the coronary ligaments in which the liver is directly attached to the diaphragm and the posterior abdominal wall. Intraperitoneal fluid cannot accumulate posterior to the liver, and any fluid observed in this area on imaging lies within the pleural space (Fig. 5–2).

- “Interface” sign. The interface between peritoneal fluid and the liver is sharp and well defined, whereas the interface between pleural fluid and liver is poorly defined. Unsharpness is probably secondary to the thickness of the diaphragm and volume averaging of curved surfaces that is influenced by slice thickness.

- “Displaced crus” sign. If the medial aspect of the diaphragmatic crura is displaced away from the spine, fluid collection is pleural in position. Fluid that lies lateral and anterior to the diaphragmatic crus is intraperitioneal in position.

- “Diaphragm” sign. On an axial CT scan, fluid that lies below or inside the diaphragm is subdiaphragmatic in location, whereas fluid that lies posterior or outside the diaphragm is pleural in position.

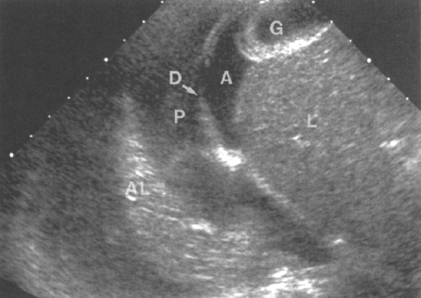

Parasagittal ultrasound is helpful in showing the relationship of the fluid to the diaphragm (Fig. 5–3).

RETROPERITONEUM

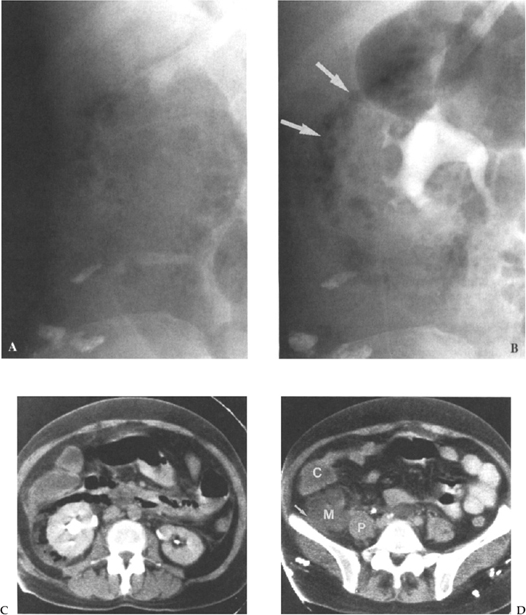

Fluid collections or abscesses may be located in the retroperitoneum. Understanding the anatomy of the retroperitoneum and those structures that border potential spaces is important in determining the location of abnormal fluid collections. Understanding of the compartmental anatomy of the abdomen is important to ensure complete treatment. As an example, pancreatic pseudocysts may dissect into different peritoneal and retroperitoneal compartments (Figs. 5–4 and 5–5). Percutaneous drainage of the infected pancreatic pseudocysts may not be curative unless the multiple localized collections in various peritoneal or retro-peritoneal compartments are adequately drained. Without effective drainage of all compartments, percutaneous therapy will probably fail.

Figure 5–5 Necrotic pancreatic abscess. Contrast-enhanced computed tomogram in 63-year-old man who presented with sepsis shows a drainage catheter (arrow) inserted in an anterior pararenal space abscess. A large gas-liquid level is seen in the anterior pararenal space along with a small amount of enhancing pancreatic tissue (P).

Figure 5–6 is an example of multicompartmental involvement by an abscess. The patient presented with what was initially thought to be primary perinephric abscess. However, CT scanning showed the primary abnormality to be a periappendiceal abscess from a ruptured retrocecal appendix. This then ruptured into the perinephric space.

Anatomy

The retroperitoneum is divided by renal fascia into three distinct compartments.2,5,6

These include (1) the perirenal space, (2) the anterior pararenal space, and (3) the posterior pararenal space.

Perirenal Space

The perirenal or perinephric space is bordered anteriorly by the anterior renal (Gerota’s) fascia and posteriorly by the posterior renal (Zuckerkandel’s) fascia (Fig. 5–7). The posterior layer of the posterior renal fascia continues anterolaterally to form the lateroconal fascia. Medially, the anterior renal fascia blends with the connective tissues surrounding the great vessels. Usually there is no communication across the midline between the two perirenal spaces. The peri-renal space contains the kidney, the adrenal gland, the renal vessels, the proximal ureter, and variable amounts of fat. There is a network of bridging septae that extend between the renal capsule and the renal fascia. The septae potentially limit the spread of pathologic processes in the perirenal space.

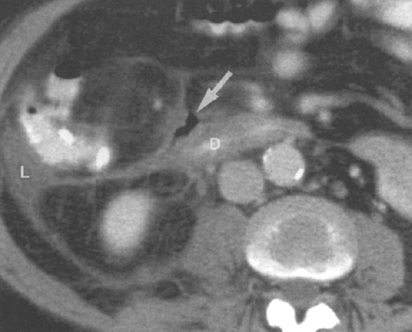

Figure 5–7 Contrast extravasation into the perinephric space. Contrast-enhanced computed tomogram in a 69-year-old man with a history of sigmoid diverticulitis resulting in distal left ureteral obstruction and hydronephrosis who now presents with increasing left flank pain. Shown is extravasation of intravenous contrast material into the perinephric space (arrow ) from a presumed ruptured fornix. Note how the contrast material is bounded anteriorly by the anterior interfascial space.

Anterior Pararenal Space

The anterior pararenal space is bordered by the posterior parietal peritoneum, posteriorly by the anterior renal fascia, and laterally by the lateroconal fascia. The anterior pararenal space contains the pancreas, the duodenum, and the ascending and descending colon (Fig. 5–8). Infection from any of these organs may spread into the retroperitoneal spaces.

Understanding retroperitoneal anatomy is important when performing interventional procedures for several reasons. Knowledge of which organs lie in the anterior pararenal space is important to better localize the potential source of abnormality. Also, as the point of fusion of the anterior and posterior renal fascia is variable, the ascending or descending colon extends posterior to the kidney in approximately 2% of subjects in the supine position and up to 10% of subjects in the prone position. Awareness of this fact is very important, especially when performing procedures such as percutaneous nephrostomy. If the retrorenal colon is not observed prospectively, then the catheter may inadvertently traverse the colon.7,8

Figure 5–8 Retroperitoneal perforation of the duodenum. Contrast-enhanced computed tomogram in a 63-year-old with abdominal pain following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography shows a small amount of free gas (arrow

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree