Percutaneous Gastrostomy, Gastroenterostomy, and Jejunostomy

I found a portion of the lung, as large as a turkey’s egg, protruding through the external wound, lacerated and burnt; and immediately below this, another protrusion which, on examination, proved to be a portion of the stomach, lacerated through all its coats, and pouring out the food he had taken for his breakfast through an orifice large enough to admit the forefinger.1,2

Based on this fortuitous accident and the resultant natural window, or traumatic percutaneous gastrostomy, Beaumont performed numerous experiments. Many of his conclusions about gastric physiology and secretion have stood the test of time and been confirmed by modern methods. Gastrostomy has since gained popularity and is now a widely accepted method for providing nutritional support or bowel decompression in a wide range of clinical scenarios.

The idea of gastrostomy as a means of delivering nutritional support was conceived by Egeberg, a Norwegian surgeon, in 1841.3 The first successful gastrostomy was performed by Verneuil in Paris in 1876.4 Surgical gastrostomy remained the only option until 1979, when Gauderer and Ponsky performed a forced percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG).5,6 Radiologic fluoroscopic-guided percutaneous gastrostomy is the newest gastrostomy technique; it was originally performed by Preshaw in 1981.7 All three methods continue to be widely used, though the nonsurgical methods are gaining acceptance due to decreased morbidity and cost.

Modifications to the surgical placement and operative gastrostomy were introduced in 1839 by Sedillot. The operative and surgical technique has been modified and tailored over the years by Woodsoe (1891), Stamm (1894), and Dupage and Janeway (1913).8 Recently, laparoscopy has been used during surgical gastrostomy.9,10

PEG placements also have been modified. The original Ponsky “pull” technique, the Sachs-Vine “push-through” technique, and the Russell “push introducer” method5,6,11,12 all continue to find use, each with its own proponents.

INDICATIONS

The provision of enteral nutritional support remains the most common indication for gastrostomy, as gastrostomies are rarely placed for bowel decompression. The use of enteral nutrition in hospitals is increasing, especially in critically ill patients. Typical patients are those with neurologic disease secondary to cerebrovascular accidents, trauma, or neurosurgery, and those with obstructive dysphagia secondary to tumor. Increased use has led to an expanding role for physicians, gastroenterologists, surgeons, and radiologists who can provide enteral access.

A large number of patients whose gastrointestinal tract functions normally may not be capable of eating because of various physiologic or anatomical difficulties with the swallowing mechanism. In these cases, short-term nutritional support has been delivered through the presence of nasogastric (NG) feeding tubes, which are now soft, small-bore catheters. They have problems of increased gastroesophageal reflux with the potential for aspiration, pharyngeal irritation, and peptic esophagitis, which are major causes of patient dissatisfaction. In two recent studies comparing percutaneous gastrostomy and NG feeding in a group of stroke patients, outcomes measured by clinical improvement mortality and nutritional state were superior with percutaneous gastrostomy and were more acceptable to patients.13,14

Early feeding in critically ill patients has become more prevalent and popular.15 Malnutrition is significant in U.S. hospital patients.16 In a critically ill patient, such as a postsurgical patient, it is now accepted that an early feeding jejunostomy can permit immediate postoperative enteral feeding even in the absence of detectable bowel sounds.17 The advantages of enteral over parenteral feeding in the nutritionally depleted patient is well established. Enteral feeding is safer, easier to administer, has more physiologic beneficial effects on the bowel, and is less expensive.18,19 A further advantage of enteral over parenteral nutritional support is the beneficial effect on the intestinal histology and structure in addition to the immunonutritional status of the patient. Enteral nutrition has the potential to decrease infective wound complications, reducing the need for antibiotic coverage and shortening hospitalization.20

Patients with Crohn’s disease, small bowel syndromes, or impaired small bowel absorption benefit from enterally administered elemental diets. The complicated cardiac surgery patient, the patient with pancreatitis, the patient with cirrhosis who is malnourished, and other patients who need organ-specific enteral support also benefit.21,22

The use of gastrostomy or gastrojejunostomy (GJ) for decompression is a well-recognized practice, but the frequency of usage depends largely on the patient population. These techniques are most commonly performed in patients with carcinomatosis for the purpose of bowel decompression, thus eliminating the need for long-term nasogastric suction. Initially, a number of authors recommend the use of large-bore (24- to 28-Fr) catheters, though smaller catheters have been shown to achieve similar results.23–25

Once one has decided on a percutaneous approach, the next decision lies between a gastric or jejunal location of the feeding tube tip, that is, a gastrostomy or a GJ placement.25 The controversy between jejunal and gastric tip placement is largely based on the risk of reflux and aspiration. Clearly, patients who are refluxing and aspirating benefit from transpyloric jejunal tube placement. Placement of the catheter tip beyond the ligament of Treitz reduces the risk of gastroesophageal reflux to virtually zero.26,27 However, placement of a jejunal tube does have one drawback: physiologically, a jejunostomy feeding tube requires a longer and slower infusion time, whereas with the gastrostomy tube (G tube) simple bolus feeding is feasible.

There are two approaches to this particular problem: One may choose to place GJ tubes in all patients,25 or one can select specific patients who are at increased risk, such as those with a documented history of reflux aspiration, with elevated gastric residual, or for whom reflux aspiration would be catastrophic.28,29 Most physicians use common sense and clinical judgment on a patient-to-patient basis in deciding whether to place a G or a GJ tube.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

As more experience is gained and as radiologists become more comfortable with percutaneous techniques, the number of relative and absolute contraindications to percutaneous gastrostomy diminishes.

Some “absolute” contraindications, when reviewed on an individual basis, may in reality be a feasible and safe option. These include patients with total gastrectomy, carcinoma involving all of the gastric wall, or extensive gastric varices. In the presence of a total gastrectomy it may be feasible to place a percutaneous jejunostomy tube (Figs. 3–1 and 3–2).30–32 In patients with gastric carcinomatosis, problems include picking a safe site (due to the risk of hemorrhage) and accomplishing gastric distention. If gastric varices are extensive, identification of a safe puncture site is the critical deciding factor. If an appropriate site can be identified, possibly with computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography, percutaneous or endoscopic methods remain appropriate.24

Relative contraindications include bleeding diathesis and an unsatisfactory access route to the stomach secondary to massive hepatomegaly, or interposed colon or ascites. Interposition of colon is a significant problem, but some manipulation with complete distention of the stomach or placement of a rectal tube may move the transverse colon out of the access plane. An infracolic route may also be used.33 When the liver is enlarged, it is not ideal to traverse that organ for the placement of a gastrostomy tube but it is possible to traverse a small portion of liver without adverse sequellae.32 Coagulopathies must be reversed prior to percutaneous gastrostomy, whereas ascites can be dealt with using a combination of preprocedure drainage and gastropexy.

TECHNIQUE AND MATERIALS

Currently, three distinct methods of gastrostomy are available: surgical, endoscopic (PEG), and percutaneous (PG). The trend has been toward nonsurgical gastrostomy because the surgical methods are carried out predominantly under general anesthesia and have a significant associated morbidity.34 Percutaneous gastrostomy with fluoroscopic guidance has been shown to be safe and effective.24,25,35–43

Preprocedure

Once the appropriateness of the procedure as the method of choice for nutritional support or bowel decompression has been established, a directed medical history, physical examination, and review of pertinent imaging must be completed. Important information, such as history of previous abdominal surgery or presence of organomegaly, may become apparent during this review. Any evidence of a bleeding abnormality should trigger an investigation and any revealed coagulopathy should be corrected prior to the procedure.

The patient must fast overnight and an NG tube should be placed, if possible. If there is difficulty in placing the NG tube due to patient intolerance or the presence of an obstructive lesion, this step can be deferred until the patient is in the interventional suite. We depend on a review of previous imaging studies and fluoroscopic assessment of the upper abdomen to check for interposition of colon or liver between the desired entry site and stomach. Some authors recommend sonographic evaluation of the liver and liver edge marking on the patient’s abdomen. Some authors also administer oral barium on the evening before the study or a limited enema at the time of the procedure for the purpose of outlining the colon.24,25,40 In our institution, with a directed physical examination, review of imaging studies, and fluoroscopic assessment of the location of both colon and liver edge, we feel confident when excluding significant organomegaly or organ displacement along the proposed puncture path.29

Procedure

All of our procedures are performed under fluoroscopic guidance with the patient supine and the left upper quadrant prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. We achieve adequate anesthesia with local anesthetic, which we supplement with intravenous morphine and midazolam to achieve conscious sedations with pertinent physiologic monitoring. If an NG tube is present, we proceed to inflate the stomach and then select an ideal skin puncture site. If the patient has an obstructive lesion or other difficulty affecting

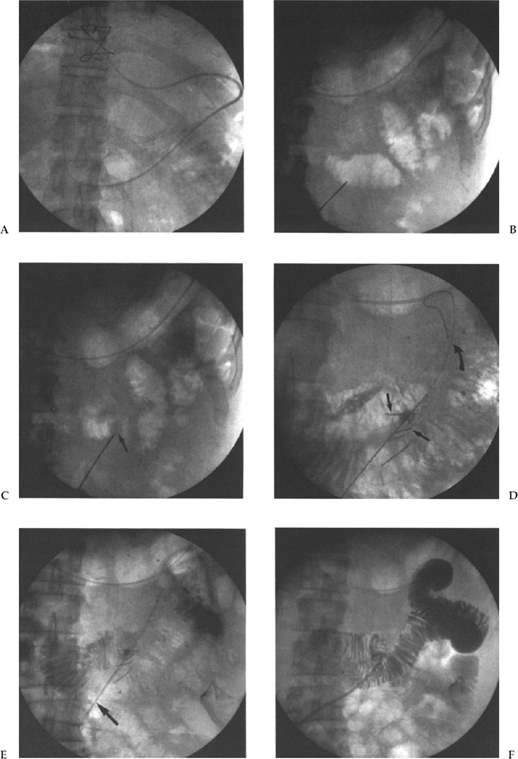

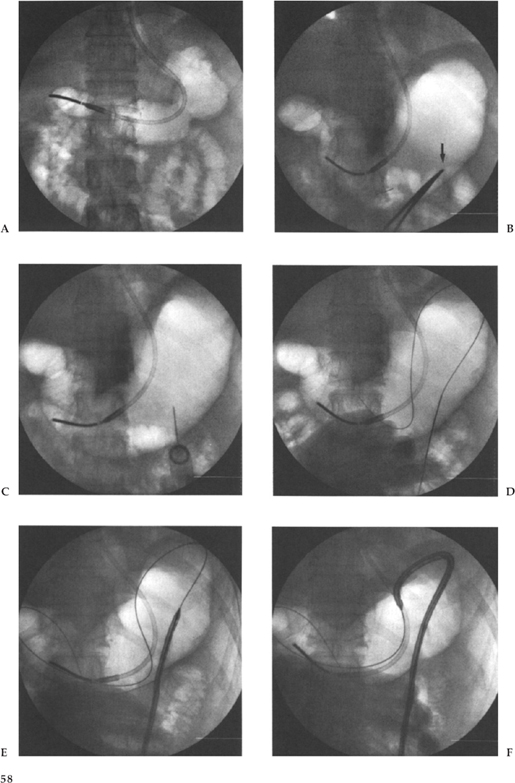

NG tube placement, then we attempt to traverse the obstruction using guide wire and catheter techniques under fluoroscopic guidance. We typically use a multipurpose catheter (Cook, Inc., Bloomington, IN) and a Bentson guide wire (Cook, Inc.). When this maneuver is unsuccessful, we inflate the stomach directly via a 22-gauge Chiba needle placed percutaneously directly into the stomach bubble. Once access has been obtained, the stomach is distended with air and a puncture site chosen (Fig. 3–3B). Some authors advocate administering 0.5 mg of intravenous glucagon for bowel paresis in all cases, but we tend to use it only when we are having difficulty in maintaining adequate gastric distention.24,43

Most radiologists use a modification of the Seldinger technique for the placement of their G tube; however, a one-step trocar method involving a single puncture has also been described.5,6 We puncture in a left subcostal position at or just lateral to the lateral margin of the rectus muscle to avoid the inferior epigastric artery and vein, following administration of sufficient local anesthetic and 1-cm skin incision. We use an 18-gauge needle and advance a 0.38-inch Coons guide wire (Cook, Inc.) (Fig. 3–3C,D). Smaller needles have been used, but we like the stiffness of the 18-gauge for puncturing the thick gastric wall. With respect to the ideal puncture site, most people choose a mid- or distal gastric body site, preferably equidistant between the lesser and greater curvatures. This choice of puncture site is an attempt to avoid the major arterial branches supplying the stomach from the left and right gastroepiploic artery and the left gastric artery. We puncture angling medially so that the track will facilitate easy access to the pylorus for potential GJ tube placement. It is critical that this puncture be observed with fluoroscopy because one must be certain that the first viscus indented by the needle is indeed the stomach, not the colon or small bowel, and then a jabbing motion, rather than a gradual pushing motion, is used to puncture the thick muscular gastric wall.

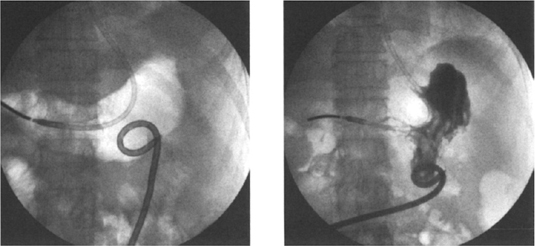

Once access to the stomach lumen has been gained and the guide wire placed, the tract is typically sequentially dilated and the gastrostomy catheter placed over the guide wire. In our institution, our technique has evolved from our previous published data29 when we used sequential dilatation, using a peel-away sheath with a 16-Fr catheter placed over the guide wire via the peel-away sheath. We presently use the Deutsch gastrostomy catheter, a modified 16-Fr Cope-loop G tube with hydrophilic coating and extralarge side-holes (Cook, Inc.). This is advanced directly over the guide wire, with the metal stiffener in place until the gastric lumen has been reached. The catheter is then further advanced over the guide wire with a jabbing motion while the stiffener is held rigid (Fig. 3–3F). With the appropriate hydrophilic coating and gastric distention to ensure an appropriate counterforce, this technique is now quicker, easier, and more successful, and it reduces the number of steps and potential errors. At the conclusion of the procedure we confirm the intragastric position by an injection of contrast (Fig. 3–3H). We do not suture or place any kind of retention device at the skin surface, preferring to allow a certain amount of freedom for movement at the skin entrance.

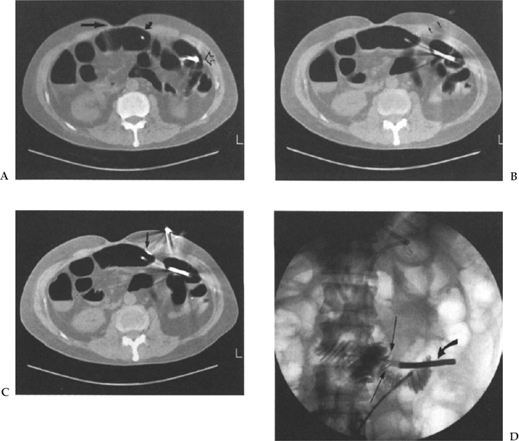

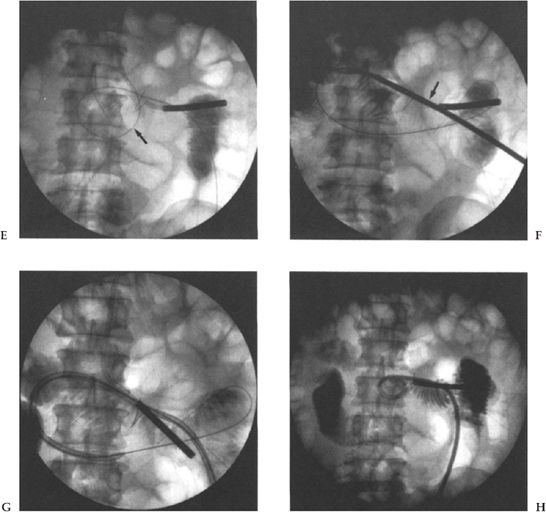

Figure 3–2 A 50-year-old man following gastrectomy for carcinoma. Jejunostomy was requested for nutritional support. (A) CT scan shows surgical defect (arrow) and distended small bowel loop immediately adjacent to anterior abdominal wall (curved arrows). Tip of nasojejunal tube is also seen (open arrow). (B) CT scan shows needle (small arrows) tract through significant soft tissue to the bowel lumen. (C) CT scan shows a T fastener (arrow) in place opposing the anterior bowel wall to the anterior abdominal wall. (D) Fluoroscopic image shows two gastropexy devices (arrows), nasojejunal-tube (curved arrow), 0.18 guide wire and dilator in situ with contrast injection to confirm intraluminal location. (E) The tract is sequentially dilated and a Coons guide wire advanced (arrow). (F) A 16-Fr hydrophilic G tube is advanced with the stiffener in place (arrow). (G) The G tube is advanced alone over the guide wire. (H) The catheter loop is formed and contrast medium injected to confirm location.

Postprocedure

We allow the gastrostomy to be used once normal bowel sounds are noted. The feedings are titrated to full strength by the dietician. We allow only liquids to be given via the G tubes and advocate the use of liquid medication formulations. The G tubes are replaced as an outpatient procedure in the interventional radiology suite at 6-month intervals, or earlier if they become clogged or displaced.

In patients who are confused or at risk for accidental removal of their tube, we employ some type of abdominal binder to discourage catheter removal, particularly during the first week, in addition to the possible deployment of gastropexy devices.

Whether some from of gastropexy is necessary in percutaneous gastrostomy remains controversial.24,29,39,44 The devices used are the Cook Cope suture anchor (Cook, Inc., Bloomington, IN) and the MediTech nylon T fastener (MediTech Corp., Watertown, MA). The devices are similar, consisting of a short metal bar with a suture attached at midpoint. They are mounted in an 18-gauge needle and deployed in the gastric lumen after the gastric wall has been punctured with a pushing wire. With gentle traction on the suture the short bar anchors the gastric wall to the abdominal wall; then the sutures are secured to the skin. As many as four gastropexy devices are used by some operators. The suture is typically cut once a tract has formed at 2 to 3 weeks. The point of gastropexy is to prevent leakage into the peritoneal cavity and to ensure the formation of a fibrous tract to decrease complications.39 We believe that the routine use of gastropexy fixation before percutaneous gastrostomy in the adult patient is not warranted because of the lack of clinical proven benefit. The stomach wall is composed of three thick muscular layers that are oriented at oblique angles to one another and form an extremely tight seal around the gastrostomy catheter, which we feel is adequate to prevent significant leakage. Saini et al propose further possible benefit of gastropexy; they believe that an element of tamponade may be achieved to prevent significant hemorrhage from a possible arterial injury.39 However, the addition of further needle punctures should increase the risk of hemorrhage to a greater degree than the proposed reduction by the placement of these T fasteners.

We do use gastropexy devices, T fasteners, or T tacks in specific situations. We typically place fasteners in patients who are at increased risk for accidental removal or who may be confused or combative, in patients with a significant volume of ascites to prevent leakage of acidic fluid around the puncture site, and for direct percutaneous jejunostomy or gastrostomy in patients following gastric surgery.45

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree