Percutaneous Colostomy

Decompression of distal bowel obstruction has traditionally belonged in the surgical domain. Although surgical colostomy is generally considered to be a safe procedure, poor patient health may make even this intervention prohibitively risky. In such cases, percutaneous techniques provide a less invasive alternative. In 1985, Crass et al described computed tomography (CT)–guided percutaneous needle aspiration of cecal gas from a massively distended cecum in Ogilvie’s syndrome.1 Since then, several modifications of the percutaneous technique have been introduced to reduce the potential for peritoneal spillage and to improve drainage and decompression. Indications for percutaneous colostomy are still evolving, and optimal approaches are not yet defined. For the majority of applications, experience is anecdotal. We compiled the limited information available on percutaneous colostomy to provide a guide for decision making regarding this relatively new realm of intervention. The following sections will identify current indications, technical considerations, and potential pitfalls of percutaneous colostomy.

INDICATIONS

- Percutaneous colostomy has been used for the following indications:

- Cecal decompression

- Ogilvie’s syndrome

- Detorsion of cecal volvulus

- Colonic irrigation for treatment of fecal incontinence

- Colonic irrigation with antibiotics

- Draining enterostomy

- Management of intestinal gas lock

Cecal Decompression and Ogilvie’s Syndrome

Massive and prolonged distention of the cecum to diameters of 10 to 12 cm or greater has been associated with an increased risk of perforation.2,3 Perforation can be expected in up to 25% of cases.3,4 The risk of perforation correlates more strongly with the duration of cecal distention than the absolute diameter.2,4 When perforation occurs, mortality reaches 43 to 46%.2,3 Common causes of cecal distention include mechanical colonic obstruction and so-called pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie’s syndrome). Cecal volvulus is responsible for 0.8 to 4.1% of cases of intestinal obstruction.5,6

ogilvie in 1948,7 and Dunlop shortly thereafter,8 described three patients with recurrent clinical signs of large bowel obstruction in the absence of organic stenoses. Both authors noted that passing flatus brought relief. These first reported patients had malignant infiltration of their sympathetic or parasympathetic nerve chains, and a disturbance of colonic innervation with parasympathetic over-reaction was assumed to cause the colonic spasm. However, autopsy studies failed to reveal inherent abnormalities of the colon or nerve chains of subsequent patients with intestinal pseudo-obstruction.9 Intestinal pseudo-obstruction can be encountered at any age but is most common in the sixth decade.2,3 Associated conditions are common (93%) and include preceding abdominal, obstetrical, or orthopedic surgery, thoracic or cardiovascular operations, trauma, myocardial infarction, and neurologic diseases.3,10 Urologic surgery is the most common associated condition in men and the second most common in women.3

Ogilvie’s syndrome is characterized by massive colonic dilatation in the absence of organic obstruction. This dilatation is most commonly segmental, involving the cecum and the ascending and transverse colon, but can reach the rectosigmoid.2 The cecum is the most common site of perforation. According to Laplace’s law, the wall tension of a hollow viscus is proportional to its diameter for a given intraluminal pressure. Increasing wall tension leads to gradual reduction and cessation of capillary, venous, and, finally, arterial flow.11 The combination of increased intraluminal pressure and ischemic impairment of the bowel wall facilitates perforation. If the intestine is decompressed and microcirculatory perfusion is restored, no serious sequelae ensue.

Despite the potential self-limiting characteristics, the overall mortality in Ogilvie’s may reach 32% even when appropriate therapy is initiated.9 Supportive care, nasogastric suction, and colonoscopic decompression are considered the initial modes of treatment. Initial colonoscopic decompression is successful in 81% of cases and can serve as definitive treatment in 64 to 86%.9,10,12 However, the rate of perforation and mortality is not negligible with colonoscopic decompression.9 Surgical tube colostomy has been reserved for endoscopic failures but also has a high mortality. It is in this setting that percutaneous approaches were first described.1,13 Crass et al1 used a posterior access to the ascending colon with a 22-gauge Chiba needle under CT guidance and manually aspirated 1500 cm3 gas from a patient with a 10-cm dilated cecum in whom other treatment modes had failed. Immediate decompression was noted and recovery ensued. Casola et al13 and vanSonnenberg et al14 obtained successful decompression in several cases with 5- to 12-Fr catheters. Based on experience gained from managing a patient with Ogilvie’s symptomatology, we speculate that colonic air locks can cause Ogilvie’s syndrome, thereby affecting treatment options (see below).

Colonic Irrigation for Treatment of Fecal Incontinence

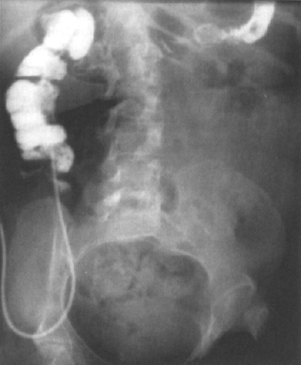

Patients with spina bifida and those having been subjected to trauma or operative procedures on the anus, rectum, or spine can lose normal function of the internal and/or external anal sphincter (Fig. 4–1). Severe constipation and secondary involuntary passage of feces may result and greatly impair lifestyle. Patients with cystic fibrosis are also at risk of developing constipation due to the highly viscous intestinal content (Fig. 4–2). Shandling and others15 used antegrade irrigation of the colon through a percutaneous cecostomy and inflatable retention balloons in the anal canal to produce controlled evacuations in a larger series of children with encopresis. The percutaneous cecostomy provides access for controlled enemas several times per week, preventing defecation accidents.15,16

Colonic Irrigation with Antibiotics

Haaga et al17 presented a case report of a 67-year-old woman who developed pseudomembranous colitis as a result of intermittent use of oral antibiotics for an infected sinus tract. The patient had been unsuccessfully treated with intravenous metronidazole and vancomycin by naso-gastric tube and enema. A retroperitoneal cecostomy was placed using a 5-Fr pigtail catheter, under CT guidance, to provide direct vancomycin instillation into the lumen of the colon. The patient did not improve, and a subtotal colectomy with ileostomy was performed. Examination of the resected specimen revealed no evidence of leak at the cecostomy site. Due to lack of clinical trials, this therapy currently has limited application. However, the potential for therapeutic benefit may exist under the right clinical conditions.

Figure 4–11 20-year-old male patient with meningomyelocele who suffered from severe constipation following spinal fusion. Tube placement (arrow) for colonic irrigation. (A) Before and (B) after tube colostomy. (Courtesy of Dr. S. Kao, University of Iowa Hospital and Clinics).

Cecostomy for Detorsion of Cecal Volvulus

Volvulus of the cecum is responsible for 0.8 to 4.1% of cases of intestinal obstruction, with surgery being the treatment of choice.5,6 Surgical approaches include tube cecostomy or appendicostomy with fixation of the cecum to the lateral abdominal wall or retroperitoneum, if the bowel is viable, and exteriorization with double-barrel enterostomy or right hemicolectomy, if the bowel is not viable.5 Patel et al18 used percutaneous anterior transperitoneal decompression of a cecal volvulus in a poor-risk surgical patient. This patient had a history of severe chronic obstructive lung disease. The anterior location of a dilated cecum abutting the anterior abdominal wall was confirmed with a cross-table lateral radiograph. A 16-gauge intracatheter needle was introduced into the dilated cecum, with immediate decompression and detorsion of the cecal volvulus. The needle was withdrawn after fecal occlusion occurred. A small pneumoperitoneum was noted, and follow-up barium enema outlined a normal cecum. Patel believed that puncture of distended cecum is not analogous to inadvertent puncture of bowel loops. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were not considered mandatory. The patient was discharged 4 days after the procedure.

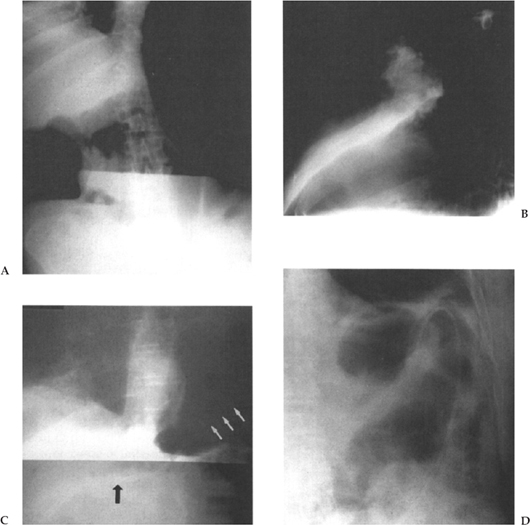

When considering cecostomy for detorsion of cecal volvulus the operator is advised to assure viability of the intestine. There may also be a theoretical advantage to placing a tube cecostomy rather than doing a simple one-step decompression. A tube tract may provide a mechanism of “fixation” that could prevent future episodes of cecal volvulus. It is important that tube cecostomy is not performed after perforation takes place. Perforation is considered to be a surgical emergency (Fig. 4–3).

Draining Enterostomy

Surgical colostomy has remained the treatment of choice for mechanical bowel obstruction. Experience with percutaneous tube colostomy for the treatment of mechanical bowel obstruction is limited. Drainage enterostomies require the use of large-bore tubes for evacuation of feces. Morrison et al19 percutaneously placed a 24-Fr catheter into the cecum for decompression and palliative drainage in a 71-year-old patient with end-stage cervical carcinoma and distal bowel obstruction. The same authors also performed a successful transperitoneal percutaneous cecostomy and drained approximately 5 L of fluid stool in an 80-year-old patient with an obstruction at the level of the transverse colon.

Percutaneous drainage of intestinal content from an obstructed system bears a considerable risk of pericatheter leak-age20,21 and requires special attention to technical matters (see below). An attractive alternative for patients with mechanical bowel obstruction is transrectal placement of self-expanding metallic stents; this procedure permits rapid resolution of obstruction and subsequent single-stage surgical reconstruction.22,23

Figure 4–3 Perforated cecal volvulus. (A) supine and (B) lateral decubitus film. Note large amount of free air.

Management of Intestinal Gas Locks

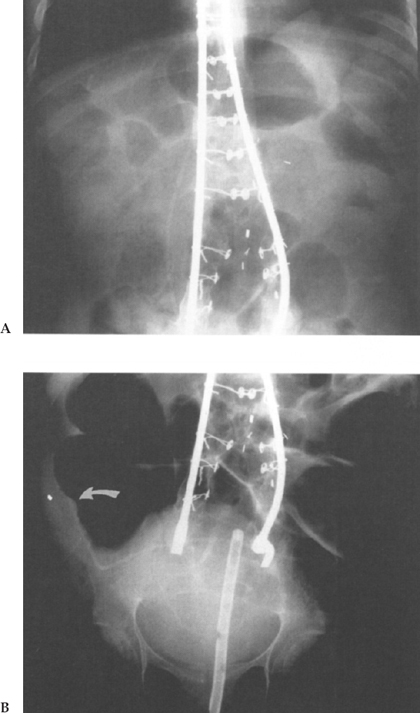

We had the opportunity to treat a 66-year-old patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis who developed acute exacerbation of chronic colonic distention. This wheelchair-confined man developed immediate hypoxemia in the recumbent position. Given the high risk of ventilator dependency of this patient, the surgical team decided that percutaneous colostomy was the procedure of choice (Fig. 4–4).

The patient was treated sitting on the raised footboard of a fluoroscopy tilt-table. Preprocedure antibiotics and intravenous fentanyl were given prior to fluoroscopic localization of a distended transverse colon. An 18-gauge needle was introduced using an anterior approach following local anesthesia with 1% lidocaine. A single T tack was also introduced to secure the bowel to the anterior abdominal wall. A one-step dilatation set (radial expanding dilator) was used to provide a 12-Fr tube access, which led to immediate decompression of the highly pressurized intestinal contents. A 12-Fr tube, and subsequently 24- and 30-Fr tubes, was used to drain intestinal content. After initial improvement and despite tube patency, the patient developed recurrent bouts of colonic distention that were attributed to formation of a gas lock at the splenic flexure. The patient was subsequently managed with a 7-Fr pigtail catheter placed in the left colonic flexure. With daily aspirations of 150 to 300 mL gas from the splenic flexure he was able to evacuate stool from the rectum and remained nondistended until his death approximately 17 months later. He succumbed to an epidural hematoma after a fall from his wheelchair.

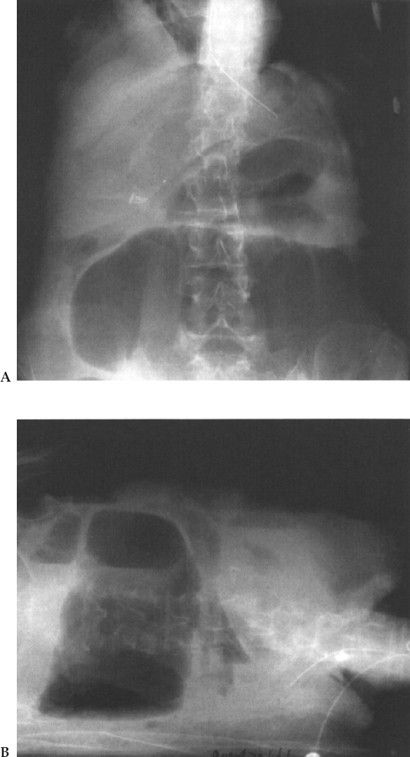

Colonic gas locks can be seen in analogy to accumulation of air in an inverted U tube connected to a fluid reservoir that drains to a lower elevation. Drainage tends to stop when the continuity of the fluid phase is interrupted by air (Fig. 4–5). Mechanical work per unit weight of fluid (foot pound force per pound of slurry) is equal to z (differential in height from the top of the reservoir to the apex of the U). The patient’s intestine apparently was not able to generate this additional force, and the gas lock caused bowel obstruction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree