Pediatric Surgical Problems

Marc A. Levitt

Alberto Peña

We can say with some assurance that,

although children may be the victims

of fate, they will not be the victims of our neglect.

—JOHN F. KENNEDY

▶ HIRSCHSPRUNG’S DISEASE

Historical Review

In 1691, Frederick Ruysch reported the autopsy findings of a child who died with what appeared to be a congenital megacolon52; however, the name for this disease originated with Harold Hirschsprung, who, in 1886, at the Pediatric Congress in Berlin, described an infant with this condition.41 The first reference relating to an absence of ganglion cells as the cause for the underlying disturbance is that of Tittle in 1901.116 In 1940, Tiffin and coworkers described the disturbed peristalsis of the aganglionic intestine.115 Robertson and Kernohan in 1938,94 and Zuelzer and Wilson in 1948, were able to correlate the functional disturbances of the distal colon with aganglionosis.123 Swenson and colleagues, in 1949, described the main principles for

the radiologic diagnosis of this condition, observations that are still useful today.112 The first surgical approach was reported by Swenson and Bill in 1948.111 Modifications of this technique, such as the Duhamel approach25 and the Soave operation,104 were developed in order to avoid some of the complications seen with the Swenson method but were based on the same principles of repair. More recently, a laparoscopic approach has been used,17,31,32,102 as well as a transanal operation.20,51

the radiologic diagnosis of this condition, observations that are still useful today.112 The first surgical approach was reported by Swenson and Bill in 1948.111 Modifications of this technique, such as the Duhamel approach25 and the Soave operation,104 were developed in order to avoid some of the complications seen with the Swenson method but were based on the same principles of repair. More recently, a laparoscopic approach has been used,17,31,32,102 as well as a transanal operation.20,51

HAROLD HIRSCHSPRUNG (1830-1916)

|

Hirschsprung was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. He passed his examinations in 1855 and was made a teacher in 1861. He was professor of pediatrics at the University of Copenhagen and head physician to the Queen Louise Children’s Hospital. Hirschsprung is best known for his description of the disease that was named after him, perhaps because of his excellent account of the condition, given that this was not the original report. Parry actually described a case that is recorded in his collected papers in 1825. Levine of Chicago, in 1867, noted the first American case. In his paper, he does not identify the pathogenicity, nor does he offer a suggestion for treatment of aganglionic megacolon. Hirschsprung contributed extensively to the pediatric literature, publishing one of the first comprehensive reports on pyloric stenosis in 1888, and he was a pioneer in the use of hydrostatic pressure for the reduction of intussusception in 1905. Although theories abounded for 50 years, Lennander in 1900 was one of the first to suggest a neurogenic origin—there was so much confusion, and there were so many differences of opinion that it was not until the 1940s that the absence of ganglion cells was believed to be the etiologic factor. (Hirschsprung H. Stuhltrúgheit neugeborener in folge von dilatation and hypertrophie des colon. Jahrb Kinderheilkd. 1888;27:1.)

ORVAR SWENSON (1909-PRESENT)

|

Orvar Swenson was born in Halsingborg, Sweden, on February 7, 1909, the son of a Mormon missionary father. The family returned to the United States and settled in Independence, Missouri. Swenson attended William Jewell College in Liberty, Kansas, and received his bachelor’s degree in 1933. He then enrolled in Harvard Medical School, graduating in 1937. Following a year as an intern at Ohio State University Hospital, he returned to Boston and to the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and the Boston Children’s Hospital, where he completed training in general surgery and in pediatric surgery in 1945. Swenson remained on the staff of these two hospitals for 5 years, during which time he ascertained the etiology of and developed a surgical treatment for Hirschsprung’s disease. In 1950, he took the position as surgeonin-chief of the Boston Floating Hospital and professor of surgery at Tufts University School of Medicine. In 1960, he moved to Chicago to become surgeon-in-chief at Children’s Memorial Hospital. In 1973, he moved on again, this time to the University of Miami, where he remained until his retirement in 1978. Swenson shared the second Mead Johnson Research Award in 1952 with Edward B. Neuhauser for their research on the elucidation, pathogenesis, and treatment of congenital megacolon. He later received the William Ladd Medal. He was recognized in 2009 in honor of his 100th birthday by a tribute in the Journal of Pediatric Surgery. (With appreciation to Avraham Belizon, MD; photograph courtesy of Keith E. Georgeson, MD.)

ALBERTO PENA(1938-PRESENT)

|

Alberto Peña was born August 16,1938, in Mexico City, Mexico. He received his medical degree at the Military Medical School in Mexico City in 1962 and completed his general surgical training at the same institution in 1966. He then became interested in pediatric surgery and decided to do a Research Fellowship in Cardiovascular Surgery at Children’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. In pursuit of his pediatric surgery training, he continued at Children’s Hospital for 2 additional years. Peña then returned to Mexico City to become the surgeon-in-chief and professor of pediatric surgery at the National Institute of Pediatrics, a position he occupied until 1985. He then accepted the post of chief of pediatric surgery and professor of surgery at the Schneider Children’s Hospital in New Hyde Park, New York. In 2005, he moved with Dr. Marc Levitt to Cincinnati where they established the Colorectal Center for Children. He is currently professor of pediatric surgery at that institution. Peña has contributed to numerous areas in the field of pediatric surgery, including deformities of the chest wall, esophageal replacement, and pancreatectomy in the newborn. However, he is best known for his innovative approach to the management of congenital anorectal malformations. Peña has received numerous honors throughout the world, including recognition by the United Nations for his work with children in Africa, the Coe Medical from the Pacific Association of Pediatric Surgeons, and Honorary Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. He continues to lecture and operate around the world and to teach pediatric surgeons his approach to the management of congenital anorectal malformations. (Courtesy of Avraham Belizon, MD.)

BERNARD GEORGES DUHAMEL (1917-1996)

|

Bernard Duhamel was born in Paris, May 11, 1917. His father was a well-known author and a member of the Academie Française, and his mother was an artist. After completing his medical studies, he began his surgical training in 1939 in Paris. Following this, he undertook a fellowship in pediatric surgery at the Sick Children’s Hospital of Paris (Hôpital des Enfants Malades). In 1954, he was appointed chairman of the Department of Pediatric Surgery at the Hôpital de Saint-Denis, and in 1955 he was elevated to professor of surgery. Duhamel made numerous contributions to neonatal surgery and wrote a number of books on surgical technique. He was elected president of the French Society of Pediatric Surgery in 1967 and was an influential member of the French Academy of Surgery. (With appreciation to Rolland F. Parc, MD.)

FRANCO SOAVE (1917-1984)

|

Born in Naples on June 14, 1917, Franco Soave completed his medical degree at the University of Genoa in 1943 and his surgical residency at the Clinica Chirurgica of the University of Turin in 1950. He returned to his alma mater in Genoa as assistant professor from 1951 to 1954 while serving in the medical corps. He later became surgeon-in-chief at the Gaslini Institute Hospital and professor and chair of pediatric surgery at the University of Genoa until his death. He published more than 160 papers and served on several editorial boards, including the Journal of Pediatric Surgery. He was awarded honorary membership in several international pediatric surgical societies and was president of the Società Italiana di Pediatria from 1970 to 1972. In 1984, he presented his milestone work on his alternative operation for Hirschsprung’s disease at the American Pediatric Surgical Association and unfortunately died the same year. (Reference: Carachi R, Young DG, Buyukunal C. F. Soave—A History of Surgical Pediatrics. Toh Tuck Link, Singapore: World Scientific Publishing; 2009—with special appreciation to Ahmed Nasser, MD.)

Pathophysiology and Embryology

Hirschsprung’s disease is an anomaly characterized by partial or complete colonic obstruction associated with the absence of intramural ganglion cells.43,69 The aganglionic portion of the colon is always located distally, but the length of the segment varies. This is the factor that determines the manifestations of the disease (Figure 3-1). The so-called typical and most frequent variation is the one in which the aganglionic segment includes the rectum and some of the sigmoid colon (Figure 3-1B), accounting for approximately two-thirds of all patients. The long-segment variety represents approximately 10% of presentations (Figure 3-1C).101 In this manifestation, the aganglionic portion may extend to any level between the splenic flexure and the descending colon. Total colonic aganglionosis is a very serious condition in which the entire colon is aganglionic, frequently including a variable length of terminal ileum (Figure 3-1D). This type also represents approximately 10% of the entire group.27 There is some debate about the existence of so-called ultrashort aganglionosis or short-segment Hirschsprung’s disease (Figure 3-1E). It is frequently confused with idiopathic constipation.

Typically, the aganglionic portion of the colon appears narrow when compared with the distended, proximal part

and has an absence of intramural, submucosal, and intermuscular ganglion cells. Increased size and prominence of nerve fibers are also seen in this area. The proximal, normally innervated portion of the colon is usually distended, and its wall is thickened because of muscle hypertrophy. Between these two areas is the “transition zone,” a cone-shaped portion of colon that is hypoganglionic, with thickened nerve trunks. An increase in the enzyme acetylcholinesterase has been demonstrated in the aganglionic colon.28,45,46 Acetylcholinesterase staining demonstrates a significant increase in the number of oversized nerve fibers located in the muscularis mucosa, the lamina propria, and the submucosa.

and has an absence of intramural, submucosal, and intermuscular ganglion cells. Increased size and prominence of nerve fibers are also seen in this area. The proximal, normally innervated portion of the colon is usually distended, and its wall is thickened because of muscle hypertrophy. Between these two areas is the “transition zone,” a cone-shaped portion of colon that is hypoganglionic, with thickened nerve trunks. An increase in the enzyme acetylcholinesterase has been demonstrated in the aganglionic colon.28,45,46 Acetylcholinesterase staining demonstrates a significant increase in the number of oversized nerve fibers located in the muscularis mucosa, the lamina propria, and the submucosa.

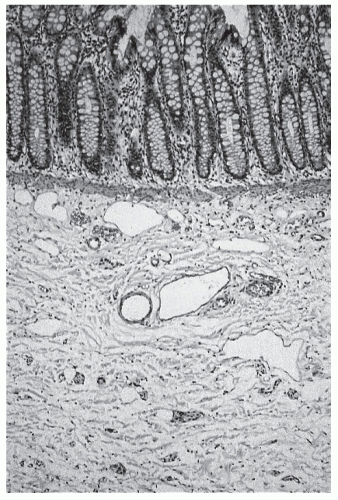

Hirschsprung’s is believed to be a disease caused by the failure in the development of tissue derived from the neural crest. As such, there appears to be an arrest in the craniocaudal migration of the neuroenteric ganglion cells from the neural crest into the upper gastrointestinal tract, down through the vagal fibers and along the distal intestine.75 As a consequence, ganglion cells are missing from Auerbach’s myenteric plexus (located between the circular and longitudinal layers of bowel wall), Henle’s plexus (located in the deep submucosa), and also Meissner’s plexus in the superficial submucosa (Figures 3-2 and 3-3). Under normal circumstances, the ganglia appear to act as a final common pathway for both sympathetic and parasympathetic influences. Their absence produces the uncoordinated contractions of the affected bowel. Spasm, lack of propulsive peristalsis, and mass contraction of the aganglionic segment40 have all been well documented, in addition to the lack of relaxation of the bowel and the spasm of the internal sphincter.18,117 The clinical result of these pathophysiologic events is partial or total colonic obstruction.

There has been a special interest in the role of nitric oxide as a neurotransmitter responsible for the inhibitory action elicited by the intrinsic enteric nerves. A lack of nitric oxide synthase (the enzyme required for nitric oxide production) has been demonstrated in the myenteric plexus of the aganglionic segment.5,76 The significance of this finding and the potential therapeutic implications are theoretically profound but have yet to be demonstrated.

Incidence and Associated Malformations

It is generally accepted that the incidence of Hirschsprung’s disease is in the range of 1 in 5,000 births.27 Although boys are much more frequently affected than girls, the longsegment manifestation is seen at least as often in female patients. Inheritance patterns seem to be multifactorial. The risk for a sibling sister of a male patient is 0.6%, whereas the risk for a brother of a female patient with long-segment disease is 18%.5,29,72

Approximately 5% to 21% of all individuals affected with Hirschsprung’s disease have an associated congenital anomaly.42 Hirschsprung’s disease has been erroneously overdiagnosed in patients with anorectal malformations because many suffer some degree of constipation.55 Another associated condition is Down’s syndrome; this anomaly is found in 5% of these infants.35

There have been developments in determining the genetic defects associated with Hirschsprung’s disease. A deletion in the long arm of chromosome 10 has been found.66 More detailed evaluation indicates that the location of this mutation is between 10Q11.2 and Q21.2 2.30,63 The deletion seems to overlap the region of the RET proto-oncogene. Patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN 2A) also have a deletion of this proto-oncogene. This genetic discovery is an important advance in the study of this complex disease, and the identification of the gene and the exact sequence of the DNA code is likely to be realized soon.72

Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis

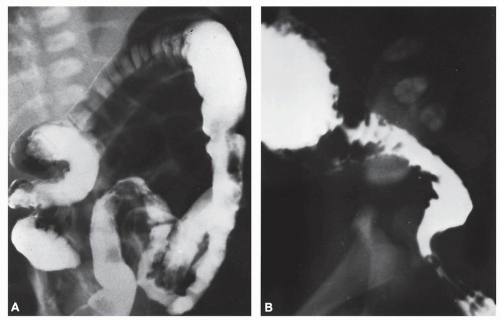

Infants suffering from Hirschsprung’s disease usually become symptomatic during the first 24 to 48 hours of life. Occasionally, a child may have minimal or absent clinical manifestations during the first days or weeks and may exhibit moderate, intermittent bouts of symptoms at a later age (Figure 3-4).

Abdominal distension, delayed passage of meconium, and vomiting are the most frequent observations. This triad of symptoms may be followed by a spontaneous or induced explosive, massively deflating passage of liquid bowel movement and gas, which dramatically improves the baby’s condition. This is followed by a period of hours or days of relative absence of symptoms followed by recurrence of the same manifestations. Stools are frequently liquid and foul smelling. When the abdomen is distended, the infant usually is very ill from sepsis, hypovolemia, and endotoxic shock. Ischemic enterocolitis with necrosis proximal to the aganglionic segment is the most serious complication. Other supervening problems are pneumatosis, intra-abdominal abscess, and cecal perforation.105 There is a 25% to 30% mortality if the disease is unrecognized or untreated.26,42

Typically, rectal examination of an ill infant with Hirschsprung’s disease produces an explosive bowel movement with immediate symptomatic improvement. The differential diagnosis includes any condition that causes intestinal obstruction in the newborn, probably the most frequent being meconium-plug syndrome. The expulsion of a plug of meconium with resolution of symptoms and the absence of other signs characteristic of Hirschsprung’s disease help to establish this diagnosis. Meconium ileus is manifested by a clinical picture consistent with that of intestinal obstruction, and the child may exhibit respiratory symptoms due to association with cystic fibrosis.24 The absence of air-fluid levels on an upright abdominal film and the “ground-glass” appearance of the lower abdomen are characteristic radiographic signs of this condition. Another disease that may lead to confusion is the small left colon syndrome. Contrast enema demonstrates a rather narrow left colon to the level of the splenic flexure but a normal caliber rectum. Symptoms usually improve following this study and resolve after several weeks. The mother is frequently diabetic. Other nonsurgical conditions that may be confused with Hirschsprung’s disease include hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, cerebral injury, opiate withdrawal, and magnesium sulfate intoxication.

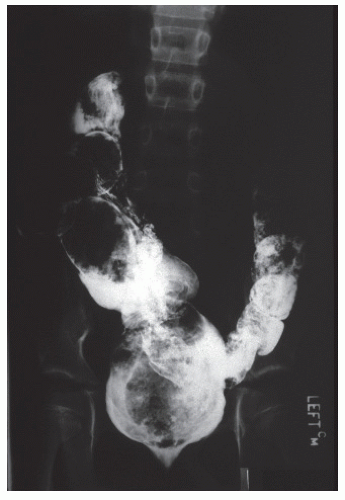

FIGURE 3-4. Contrast study of a young man with presumed short-segment Hirschsprung’s disease with lifelong constipation. Note the dilated bowel with considerable fecal impaction. |

Patients with Hirschsprung’s who survive despite inadequate treatment or who have relatively mild symptoms ultimately develop the classic clinical picture initially described for this condition. Nowadays this is quite rare. These children suffer severe constipation with an enormously distended abdomen. The proximal colon is huge and full of inspissated fecal material (Figure 3-4). At this stage, the diagnosis may be confused with severe idiopathic constipation. In the latter condition, children usually become symptomatic after the sixth month of life; they neither vomit nor become seriously ill and often experience overflow incontinence or encopresis, a constant, chronic soiling. Rectal examination in such children reveals a fecal impaction just above the anal canal. Patients with Hirschsprung’s disease may have an empty rectum, or examination may disclose only a small amount of feces.

Diagnosis

Radiologic Studies

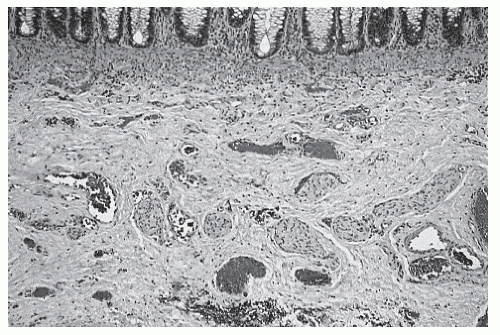

It is very difficult to differentiate a distended colon from distended small bowel based on a plain abdominal film of a neonate with intestinal obstruction. Therefore, one can only suspect the diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease from this study. The presence of air-fluid levels is evidence of obstruction, but it is nonspecific. An enema examination performed with water-soluble contrast material is the most valuable radiologic study for establishing the diagnosis.

No bowel preparation is required. The infant is placed in a lateral position, and a rectal tube is introduced to barely above the anal canal. Injection of contrast is optimally controlled by hand with a syringe. The introduction of a catheter beyond the limit of the anal canal will risk a misdiagnosis because the tip may reach the distended colon and result in injection above the aganglionic portion. The dye is instilled until it reaches the distended portion of the intestine.

This study may reveal a very distended proximal colon, the transition zone, and a narrowed distal rectosigmoid (Figure 3-5). The older the patient, the more obvious the size difference between the normal ganglionic intestine and the abnormal aganglionic bowel. Therefore, sometimes the typical changes are not very obvious during the neonatal period. A second contrast enema performed a few days or weeks later may show a much more dramatic appearance than that seen previously (Figure 3-5B). Generally, however, the transition zone is recognized in most newborns. Contrast enema is less accurate in infants with very short aganglionosis or when the entire colon is involved.97 In instances of total colonic aganglionosis, contrast enema may reveal a rather short colon, with retraction of the hepatic and splenic flexures and straightening of the sigmoid.

Anorectal Manometry

Normally, when the rectum is distended with a balloon, pressure in the anal canal falls because of internal sphincter relaxation (the rectoanal inhibitory reflex). In infants with aganglionosis, this reflex is absent.118 This abnormal response has been

interpreted as diagnostic for this condition. However, this test has several limitations, the primary ones being the technical difficulty of evaluating the newborn and the mismatch of the manometry balloon to the wide variety of colonic luminal diameters. We, therefore, do not use this test in our clinical practice.

interpreted as diagnostic for this condition. However, this test has several limitations, the primary ones being the technical difficulty of evaluating the newborn and the mismatch of the manometry balloon to the wide variety of colonic luminal diameters. We, therefore, do not use this test in our clinical practice.

Rectal Biopsy

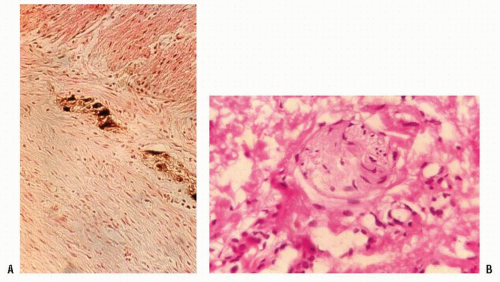

The confirmation of the diagnosis is based on the absence of ganglion cells and the presence of hypertrophic nerves in an adequate rectal biopsy (Figure 3-6). The specimen must be taken at least 1.5 cm above the pectinate line. The traditional

full-thickness rectal biopsy has obvious diagnostic value but requires good rectal exposure and a general anesthetic. Suction rectal biopsy is easily performed, is associated with virtually no risk of perforation, and does not require an anesthetic.23,74 The specimen usually measures 1 × 3 mm and should include mucosa and submucosa. Interpretation requires expertise.

full-thickness rectal biopsy has obvious diagnostic value but requires good rectal exposure and a general anesthetic. Suction rectal biopsy is easily performed, is associated with virtually no risk of perforation, and does not require an anesthetic.23,74 The specimen usually measures 1 × 3 mm and should include mucosa and submucosa. Interpretation requires expertise.

The presence of large amounts of acetylcholinesterase in the mucosa and submucosa helps to make the diagnosis and is used in many centers.28,45,46,69 The absence of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phospate diaphorase-containing neurons and an increase in the amount of acetylcholinesterase-containing nerve bundles are all characteristic.68,70 Furthermore, nitric oxide synthase is a candidate neurotransmitter responsible for relaxation of the internal anal sphincter.70

Opinion

There is considerable difference of opinion with respect to the reliability of the various diagnostic methods. It is our impression that the most important variable is the experience of the radiologist, physiologist, and pathologist. We have found the contrast enema to be the most valuable diagnostic test, with rectal suction biopsy a means for confirming the clinical and radiologic impression. Although biopsy may establish the diagnosis when the specimen is obtained through the rectum, it reveals nothing about the transition zone site. That valuable piece of information must be obtained radiologically, clinically, and with full-thickness biopsy analysis, guided by an experienced eye in the operating room during the definitive operation. The aganglionic segment is contracted; the transition zone is thick and leathery; and a normal caliber, smooth colon is found above the transition zone.

Management

Medical Treatment

Bowel irrigation with saline solution is an extremely valuable procedure for the emergency management of distension and vomiting. By decompressing the colon, irrigations may dramatically improve the condition of a very ill infant, as well as to prevent and treat enterocolitis.

It is extremely important to clarify the difference between an irrigation and an enema. To confuse these two terms may be dangerous for babies with Hirschsprung’s disease. An enema is a procedure in which a determined amount of fluid is instilled into the rectum and colon. The fluid is expected to be spontaneously expelled. A rectal irrigation, conversely, is a procedure in which a large tube (e.g., 24F) is introduced through the rectum, and small amounts of saline solution are instilled through the tube in order to cleanse the bowel. The rectal and colonic content is expected to drain through the lumen of the tube. The tube is then rotated in different directions and moved in and out. The operator continues to instill small amounts of saline solution, allowing the evacuation of gas and liquid stool through the tube.

Patients with Hirschsprung’s disease suffer from a very serious dysmotility disorder. An enema, as defined here, may worsen the problem because the patient does not have the capacity to expel the infused volume of fluid. With an irrigation, the patient benefits from the evacuation of the rectosigmoid contents through the lumen of the large tube. Essentially the tube overcomes the functional distal obstruction.

Surgical Treatment

General Principles

Patients with Hirschsprung’s disease can usually undergo a primary procedure within the first few months of life.11,13,15,103 The circumstances for performing the surgery are different from country to country, and there is often quite a bit of variability in the experience of surgeons and their access to resources.90 In addition, the availability of fully trained, experienced clinical pathologists may be problematic. If one is to perform a primary neonatal pull-through procedure, the surgeon must rely on frozen-section analysis. For this, he or she must interact with an experienced pathologist. In the very ill, low-birth-weight newborn, one who suffers from associated defects or concomitant serious medical conditions, or in the absence of pathologic support, an initial fecal diversion may be required.

In addition to the issue of whether the performance of a colostomy is appropriate, there is a difference of opinion as to the type and the location of the stoma. In our experience, if diversion is to be considered, an ileostomy is an effective and safe method for decompressing the bowel in the vast majority of infants with this condition. By using this location, the risk of opening the stoma in an aganglionic area is much reduced. And, the sigmoid mesentery is unaffected by the diversion. It is a particularly useful option in the emergency situation, especially if the surgeon cannot rely on the radiologist, or if a pathologist capable of making the diagnosis based on frozen-section analysis is unavailable.

Many surgeons advocate the creation of the stoma just above the transition zone, a leveling colostomy, which requires confirmatory frozen-section analysis. This alternative obligates one to pull the colostomy down at the time of the definitive repair. Obviously, the advantage to this approach is that the child will require only a two-stage procedure, whereas an ileostomy commits the surgeon to a three-stage operation.

Definitive Operations

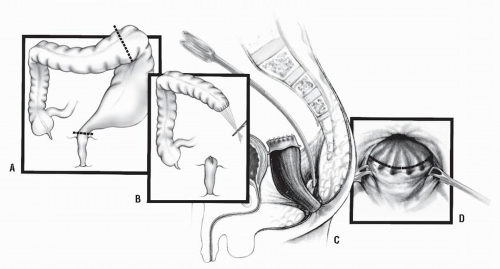

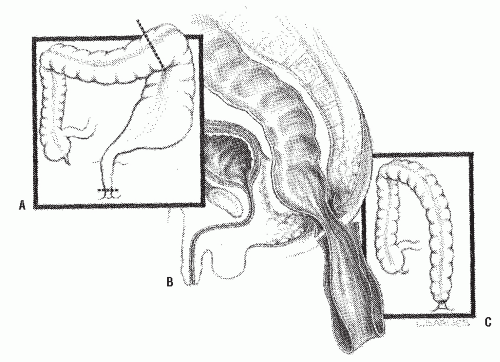

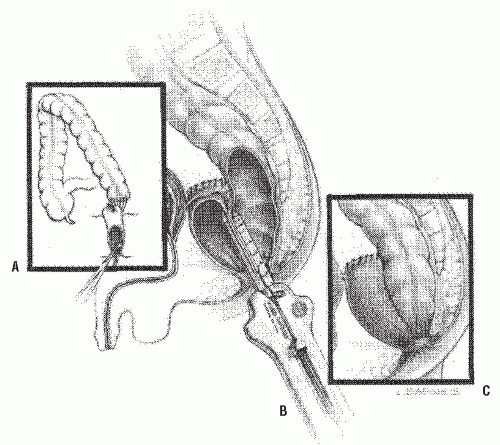

Swenson Procedure. Swenson and Bill described a transabdominal dissection with resection of the aganglionic portion of the colon, including that of the most dilated portion of the bowel (Figure 3-7A).111 Typical Hirschsprung’s disease may require only mobilization of the sigmoid arcade and sometimes the splenic flexure, but the long-segment type may necessitate mobilization of even the right colon in order to obtain sufficient length. Freeing of the aganglionic area below the peritoneal floor is carried out by precise dissection as close as possible to the rectal wall down to the level of the levators (Figure 3-7B). Anastomosis is effected by a transanal, hand-sewn technique (Figure 3-7C). The abdominal component nowadays is usually performed laparoscopically. The transanal dissection includes fullthickness rectal wall.

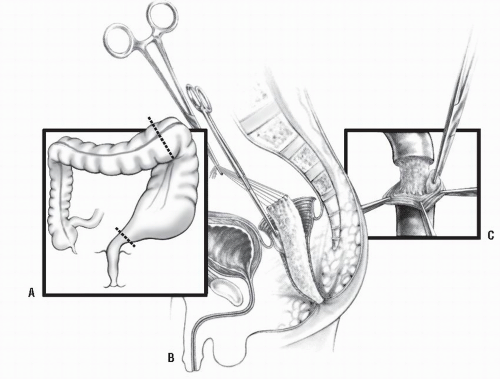

Duhamel Procedure. Duhamel’s procedure25,102 was devised in order to avoid the extensive pelvic dissection required of Swenson’s operation. This is accomplished by preserving the aganglionic rectum and dividing the bowel at the peritoneal reflection as distally as possible (Figure 3-8A).

The rectal stump is then closed (Figure 3-8B). Normal (i.e., ganglionic) intestine, usually above the most dilated portion, is pulled through a presacral space that has been created by blunt dissection (Figure 3-8B,C). The posterior rectal wall is incised above the dentate line, entering the previously dissected retrorectal space (Figure 3-8D). The new, normally innervated colon is pulled through the rectal incision, and a gastrointestinal anastomotic stapler is used to effect the anastomosis to the aganglionic rectum (Figure 3-9A,B). The posterior wall of the colon is also sutured to the edge of the proctotomy (Figure 3-9C). The anastomosis between the colon and the aganglionic

rectum must be created as wide as possible, and the rectal stump as small as possible.

The rectal stump is then closed (Figure 3-8B). Normal (i.e., ganglionic) intestine, usually above the most dilated portion, is pulled through a presacral space that has been created by blunt dissection (Figure 3-8B,C). The posterior rectal wall is incised above the dentate line, entering the previously dissected retrorectal space (Figure 3-8D). The new, normally innervated colon is pulled through the rectal incision, and a gastrointestinal anastomotic stapler is used to effect the anastomosis to the aganglionic rectum (Figure 3-9A,B). The posterior wall of the colon is also sutured to the edge of the proctotomy (Figure 3-9C). The anastomosis between the colon and the aganglionic

rectum must be created as wide as possible, and the rectal stump as small as possible.

FIGURE 3-7. Swenson’s procedure. A: Bowel resection including aganglionic and distended bowel. B: Pull-through of normally innervated colon. C: Anastomosis completed. |

FIGURE 3-9. Duhamel’s procedure. A: Retrorectal pull-through. B: Gastrointestinal anastomosis stapler used to join the colon to the aganglionic rectum. C: Completed reconstruction. |

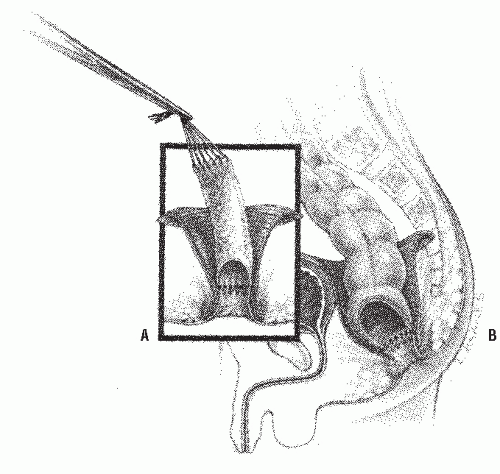

Soave Procedure. The Soave procedure104 removes the aganglionic rectosigmoid by a submucosal endorectal dissection, theoretically minimizing the risk to pelvic nerve injury associated with the Swenson procedure. The normally innervated colon is passed through a rectosigmoid muscular cuff. The cuff (outer wall of the rectum) that is aganglionic, if left too long, can cause obstructive symptoms.54 Originally, Soave left a portion of the pulled-through colon protruding beyond the anal skin margin, which was then excised at a second operation 1 week later. This two-stage procedure was modified by Boley into a one-stage procedure by effecting a primary anastomosis to the anal verge.8 The endorectal dissection is initiated usually 1 or 2 cm above the peritoneal reflection (Figure 3-10). The normal, ganglionic colon is anastomosed to the anorectal mucosa (Figure 3-11). The abdominal component here is also usually done with laparoscopy.31,32

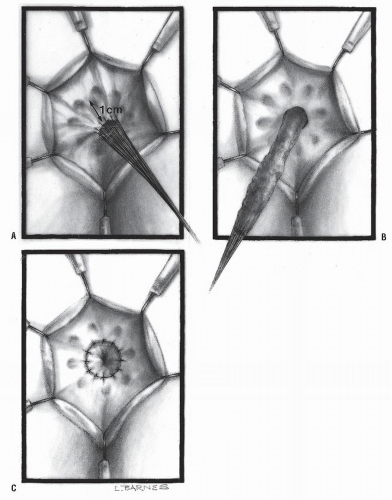

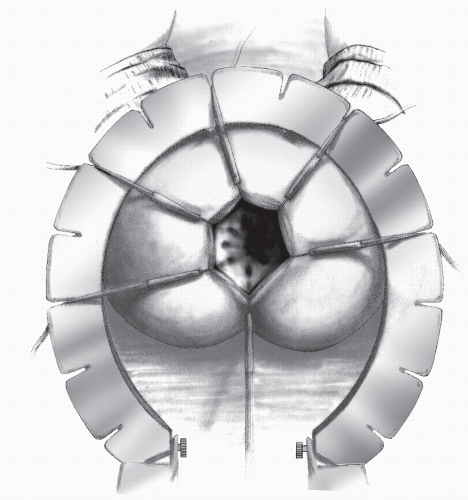

In 1998 and 1999, de la Torre and Ortega and Langer et al. in different reports described a transanal-only approach to the management of Hirschsprung’s disease.20,51 Others quickly adopted the concept and published large series with this operation.50 The basic concept consisted of approaching the disease through the anus. A Lone Star retractor is used (Figure 3-12). The circumferential traction exposes the anal canal, the pectinate line, and the rectal mucosa. Multiple fine sutures are placed in the rectal mucosa in a circumferential manner in order to exert uniform traction to facilitate the dissection of this part of the bowel and to carefully preserve the dentate line. A circumferential incision about 1 cm proximal to the dentate line just distal to the multiple silk sutures is performed, and the dissection of the rectum commences (Figure 3-13A,B).

Some surgeons prefer to perform this transanal dissection submucosally (endorectally), (Soave-like) but we prefer a full-thickness dissection (Swenson-like). A specific recommendation in both of these dissections is to stay as close as possible to the rectal wall in order to minimize risk of injury to important pelvic nerves. If performing a Soave, the submucosal dissection should only be 1 to 2 cm. The peritoneal reflection is soon reached. As the dissection progresses, full-thickness biopsies are taken that are sent to the pathology department to look for ganglion cells. The biopsy must be full thickness because it is possible to have ganglion cells in the muscularis layer but have hypertrophic nerves in the submucosa. The transition zone sometimes demonstrates an area of hypoganglionosis, and the nerve trunks are thick (greater than 50 microns). It is recommended that one continue the dissection until reaching an area somewhere above the transition zone to be certain that normal, ganglionic bowel is pulled down. The surgeon looks for a smooth-walled nondilated segment of bowel. The normal, ganglionic bowel is transanally anastomosed to the anal canal 1 cm above the pectinate

line (Figure 3-13C). Considering that most patients with Hirschsprung’s disease have a transition zone in the sigmoid colon, it is often possible to repair the entire defect using only the transanal approach without a laparotomy or laparoscopy. However, when the transition zone is located higher, or the surgeon does not feel safe in conducting this dissection further from below, then one must open the abdomen or perform a laparoscopic-assisted procedure in order to mobilize the colon.

line (Figure 3-13C). Considering that most patients with Hirschsprung’s disease have a transition zone in the sigmoid colon, it is often possible to repair the entire defect using only the transanal approach without a laparotomy or laparoscopy. However, when the transition zone is located higher, or the surgeon does not feel safe in conducting this dissection further from below, then one must open the abdomen or perform a laparoscopic-assisted procedure in order to mobilize the colon.

FIGURE 3-10. Soave’s procedure. A: Resection of most dilated portion of the bowel. B,C: Endorectal dissection. |

FIGURE 3-11. Soave’s procedure. A: Endorectal dissection completed above the dentate line. B: Ganglionic bowel pulled through and anastomosis completed. |

FIGURE 3-12. A Lone Star retractor in position with hooks in place to provide exposure for the dissection. |

Some surgeons advocate commencing the procedure laparoscopically, performing a biopsy to identify the transition zone, mobilizing the sigmoid colon laparoscopically, and then dissecting transanally.

It is important to keep in mind that the resection must include not only the aganglionic part but also the dilated part of the bowel. Pulling down a very dilated segment of colon even though it may be ganglionic will result in severe constipation later in life because dilated bowel tends to lose its peristaltic ability.54

Opinion

At our institution, we are often referred patients who have undergone a procedure for Hirschsprung’s disease and who subsequently suffer from serious complications.54,85 The most common problem as a consequence of Duhamel’s procedure is persistence of an aganglionic, large, blind rectal pouch. This tends to grow with time and to produce chronic fecal impaction with multiple related symptoms.

Following a Soave procedure, we have seen patients suffering from perianal fistulas and abscesses related to the presence of islands of mucosal cells trapped in the pelvis. This is a consequence of a technical error that occurred during the endorectal dissection. These patients require an operation to excise these cells. We have actually even found pieces of bowel that have been left trapped in the pelvis. In addition, an excessively long or a scarred Soave cuff can obstruct the ganglionic pull-through.54

A feared and unfortunately frequent complication is fecal incontinence. This is most likely related to injury to the

continence mechanism during one of these procedures.57 The anal canal can be inadvertently resected or the sphincters can be damaged by overstretching. All operations for this condition are designed to prevent this from happening, provided the procedures are performed properly. Dehiscence, retraction, stricture, abscess, and fistula are all the result of technical errors.

continence mechanism during one of these procedures.57 The anal canal can be inadvertently resected or the sphincters can be damaged by overstretching. All operations for this condition are designed to prevent this from happening, provided the procedures are performed properly. Dehiscence, retraction, stricture, abscess, and fistula are all the result of technical errors.

A complication one understands poorly is enterocolitis. This problem is a true challenge for pediatric surgeons. Although the etiology is not known, it is believed that fecal stasis is a predisposing factor. Anatomic causes for obstruction such as a cuff or retained dilated segment can lead to enterocolitis.54

Constipation after surgery should be anticipated and aggressively managed. When a pull-through procedure leaves behind a portion of significantly dilated colon, these children will suffer from constipation. A dilated colon is almost as severe a pathologic entity as an aganglionic segment, and as previously mentioned, it should be resected at the time of the pull-through. Despite meticulous attention to surgical technique, constipation still occurs in approximately 15% of cases. Hypermotility resulting from resection of the rectosigmoid reservoir may also occur, but this is less common. A contrast enema helps differentiate between these

two conditions; a dilated colon means constipation, whereas a nondilated colon implies hypermotility.

two conditions; a dilated colon means constipation, whereas a nondilated colon implies hypermotility.

Surgical Management of Total Colonic Aganglionosis

When the diagnosis of total colonic Hirschsprung’s is made, an ileostomy is required initially, and the definitive operation ideally delayed until the child can sit on a toilet. This avoids the often seen perianal excoriation. Management of these patients while they have an ileostomy requires careful monitoring of growth. Sodium loss is also a source of concern with children often requiring oral sodium supplementation. We perform an ileoanal pull-through using a Swenson-like technique for the definitive reconstruction. Many surgeons, however, use an ileo-Duhamel approach.

Opinion.Long-term follow-up of patients with total colon aganglionosis has demonstrated that the concept of integrating a portion of aganglionic colon with the normal ganglionic, pulledthrough bowel (often employed in the past) in order to minimize stool retention and frequency has proved to be erroneous. Stasis of stool in the small bowel produces bacterial proliferation and an inflammatory process. Rather than absorbing water, very often the intestine secretes it into the lumen, producing what is essentially a secretory diarrhea. It is not uncommon that resection of these pouches becomes necessary in order to address the problems of malnutrition and fluid loss.54,85 We, as well as others, believe that a straight ileorectal anastomosis is the preferred option because of the better long-term results.113

Total Intestinal Aganglionosis

Patients can have total (extending to the stomach) or neartotal intestinal aganglionosis. Such children require an intestinal transplantation to survive.

Commentary

Hirschsprung’s disease is a subject of active research and study. This has led to the production of a large number of publications causing one to hope that many of these children will soon realize the benefits. For example, considerable effort has been made in transplanting ganglion cells.96 Moreover, advances in the field of genetics should ultimately allow us to predict which individuals are at risk for having children with this condition.72 Additionally, genetic engineering could one day be used to prevent this condition, an exciting area of exploration indeed.

EDOUARD-PIERRE-MARIE CHASSAIGNAC (1804-1879)

|

Edouard Chassaignac was born on December 24, 1804, in Nantes, France. He received his medical school education at the University in Nantes and graduated in 1835. His great forte was the design of new instruments, and he was an ingenious experimenter. For example, he perfected the use of the new product, rubber, for use as a fenestrated drain and developed the concept of the occlusive dressing for wounds. He became surgeon to the Lariboisiàre in 1852 and is recognized as the first surgeon to perform a colostomy for the management of an anorectal malformation. Other signal contributions included his classic dissertation on fractures of the femoral neck, his treatise on suppuration and surgical drainage, his classification of breast abscess, and his book (The Subject of Surgical Anatomy and Pathology) in which he relates his experiences in clinical surgery. He is also eponymously recognized for his description of the carotid (cervical) tubercle (Chassaignac’s tubercle). In 1861, he was awarded the Legion of Honor, and in 1868 he was named a member of the Academy of Medicine. Chassaignac died in Versailles on August 26,1879.

▶ ANORECTAL MALFORMATIONS

Historical Review

Anorectal malformations have routinely been classified by the term “imperforate anus”; although the vast majority are “perforate,” the rectum just terminates in an abnormal anatomic location. The condition has been recognized since antiquity (e.g., by Paulus Aegineta of Greece).1 For many centuries, physicians understood that by creating an orifice in the perineum many of the children with imperforate anus survived, some even with normal bowel function. Unfortunately, an anal stricture was often a consequence. If the condition went uncorrected, intestinal obstruction and death frequently resulted. Ancient operations consisted of making an incision in the perineum deep enough to open the rectal pouch and to obtain meconium. The surgeon packed the wound and changed the packing daily in an attempt to create a permanent perineal orifice. The primary concern was directed toward survival of the infant, and therefore, these operations took only a few minutes and were obviously undertaken without anesthesia, blood transfusion, or other adjunctive measures. In 1835, Amussat (see his biography, Chapter 24) was the first person not merely to open the rectal pouch, but also to suture it to the skin.3 In retrospect, perhaps those who survived that operation were children who had “low malformations.” Conversely, those for whom the operation was unsuccessful probably had a malformation wherein the rectum was higher in the pelvis.

Chassaignac, in 1856, was the first person to perform a colostomy for the treatment of an anorectal malformation.14 Hadra, in 1886, performed the first abdominoperineal procedure.37 For the first part of the 20th century, most surgeons used a preliminary colostomy and an abdominoperineal pullthrough for the treatment of high malformations, and a perineal approach without a colostomy for so-called low malformations. In 1930, Wangensteen (see his biography, Chapter 23) and Rice described the invertogram, an x-ray film taken during the newborn period with the infant’s head down, in order to measure the distance between the rectal pouch and the skin as a criterion for determining the height of the malformation.122

In 1948, Rhoads and colleagues reintroduced the neonatal one-stage abdominoperineal procedure.93 In 1953, Stephens noted the importance of preservation of the puborectalis sling in maintaining fecal continence.106,107,108 He proposed an initial sacral approach followed by an abdominoperineal operation, if necessary. Since 1980,21,83 these malformations

were found to be ideally approached through a posterior sagittal incision, using an electrical stimulator to identify the sphincter complex.78,79,80,83 This technique was instrumental in revealing the very important anatomic area of the pelvis that, until 1980, was a matter mostly of speculation.

were found to be ideally approached through a posterior sagittal incision, using an electrical stimulator to identify the sphincter complex.78,79,80,83 This technique was instrumental in revealing the very important anatomic area of the pelvis that, until 1980, was a matter mostly of speculation.

Incidence

Most authors report that 1 of every 5,000 newborns have an anorectal malformation.10,98,120 Male infants seem to suffer from this condition more frequently than females. The most common type of malformation seen in boys is rectourethral fistula, and the most common type of anomaly in girls is rectovestibular fistula. There is an increased incidence of imperforate anus in children with Down’s syndrome who frequently have a lowlying rectal pouch without a genitourinary or perineal fistula.119

Embryologic Considerations

Anorectal malformation defects develop during gestational weeks 4 to 12.107 The urinary, genital, and rectal tracts empty into a common channel, the cloaca. Ultimately, they will be segregated by the urorectal septum during its craniocaudal descent, separating the cloaca into an anterior urogenital sinus and a posterior intestinal canal. Two lateral folds of the cloaca also move simultaneously toward the midline. The perineal mound appears to be the caudal extension of the urorectal septum, which develops into the perineal body. In the male, the inner and outer genital ridges meet to form the urethra. In the female, these ridges do not coalesce but form the labia minora and majora. Various types of failures in this process have been postulated to explain each of the anorectal malformations. The resulting defects constitute a spectrum that ranges from the most severe examples (e.g., caudal regression and persistent cloaca) to the more easily managed concerns (rectoperineal fistula).

Classification

In our experience, the posterior sagittal approach to these malformations has permitted the opportunity for directly exposing the anatomy of each of these defects. This has led to important therapeutic implications in addition to those of terminology and classification, making previous classifications now obsolete.49,109,110

TABLE 3-1 Classification | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree