Paediatric clinical dietetics

Paediatric clinical dietetics

Introduction

Dietetics is defined as the application of the principles of nutrition to the selection of food and the feeding of individuals and groups

1. Clinical dietetics covers the nutritional management of sick infants and children (either in an acute or chronic phase) to fulfill their requirements in a clinical and/or outpatient setting. This can be done in terms of adjusting the diet, adjusting menus, recommending certain foods, and/or using commercial nutritional supplements.

There are infants with certain diseases (metabolic, allergies) who need special enteral formulas to adapt the whole diet. Others may need supplementation, using nutritional modules that are added to a formula (

Table 16.1).

Many studies demonstrate the advantages of nutritional supplementation in different groups of patients, improving the evolution of the disease, and decreasing the incidence of

complications

3. Some children may require the use of paediatric supplements to increase their poor oral intake (

Table 16.2). Other children may need a complete nutritional support via nasogastric tube (

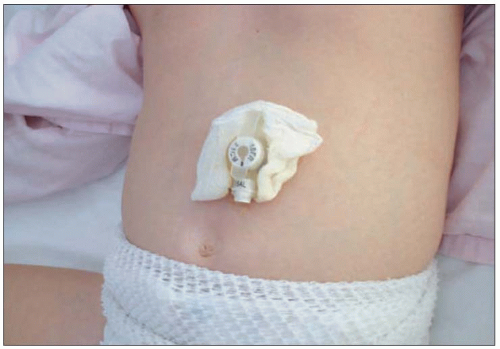

16.1), via gastrostomy (

16.2), or by means of parenteral nutrition when the gastrointestinal tract is not functional. An adequate nutritional status allows a normal growth and development. Growth can be compromised in the presence of a chronic disease especially when it coincides with peaks of growth (infancy, puberty).

During growth, size increases and body composition changes. This implies certain nutritional requirements which are higher than those of the adult. Besides, the immaturity at birth involves special requirements in terms of

quality of nutrients, types of foods, and a limited response to overloading which can lead to complications. Therefore, there is a need to assess adequately nutritional status before starting any nutritional support.

Nutritional assessment

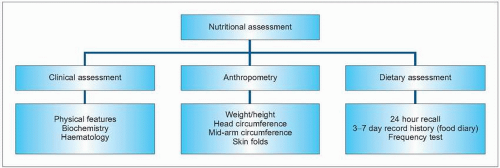

In the dietetic approach to a sick infant or child, it is essential to perform a correct nutritional assessment. There are a number of methods assessing specifics aspects of nutritional status, but no one measurement will give an overall picture of the status of all nutrients (

16.3).

Clinical assessment

This includes a complete medical history and physical examination (

Table 16.3). It is important to watch out for the constitution of the child; especially differentiating those who are skinny by genetics from those who have lost muscle mass. The presence of malnutrition signs, such as abdominal distension, presence of oedema, and hepatomegaly, should be evaluated, along with mood and behaviour as children may be apathetic and irritable. Biochemistry and haematological tests are also useful (

Table 16.4).

Anthropometry is a physical examination which provides an indirect assessment of body composition and development. The child is growing continuously, and in each moment there is an ideal weight for a determined height. In acute malnutrition the weight may be altered maintaining the rate of height, although in a chronic state this rate also appears altered. This growth retardation is an important sign of malnutrition.

Weight measurement is an easy and routine procedure (

16.4). Children can be weighed in beam balance scales or electronic scales. Weight shows variability during the day, and it would be advisable to weigh always at the same time and with the same conditions

7. Height measurement for infants and children less than 2 years old, is measured supine (

16.5). From 2 years old, standing height is then measured whenever possible (

16.6).

Skinfolds provide information about the changes produced in the subcutaneous components of the fat and fat-free mass. There are seven sites of measure: triceps, abdomen, chest, thigh, suprailiac (iliac crest), mid-axillar, and subscapular. They are measured with a skinfold caliper. Mid-arm circumference is useful to determine the state of muscle mass, as this area is hardly affected by oedema. This measurement is used in conjunction with the skinfold

triceps to differentiate between lean and fat

.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access