Paediatric appendicitis

Adolfo Bautista Casasnovas MD

Introduction

Acute appendicitis is a common paediatric surgical disease requiring urgent attention. Appendectomy is the most common surgical procedure performed for acute abdominal pain in children (15.1)1. The diagnosis of acute appendicitis in childhood can sometimes be difficult.

The incidence of acute appendicitis has been estimated at about 1 case per 1,000 children per year, with slightly higher incidence among boys. The lifetime risk of appendicitis is estimated to be 8.67% for boys and 6.7% for girls. Incidence among preschool children is unusual, but in this age group delayed diagnosis and complications are more frequent. Around one-third of children with acute appendicitis are found to be perforated at surgery.

Children who have appendicitis are twice as likely to have a positive family history as are those with right lower quadrant pain, but no appendicitis2. Early diagnosis continues to be the most important factor for prognosis. The rate of negative appendectomy is considered acceptable for up to 10% of laparotomies for suspected acute appendicitis. Paediatric surgeons performed significantly fewer negative appendectomies than general surgeons3.

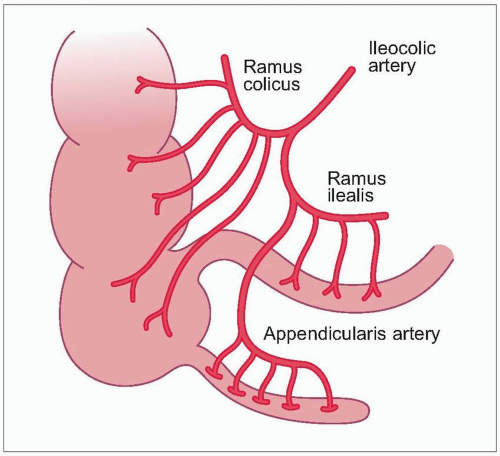

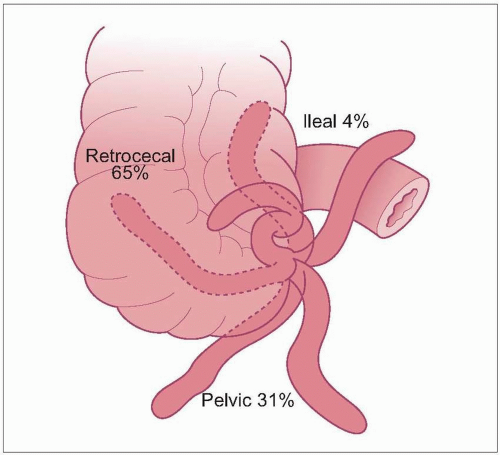

The development of the caecum and appendix begins in the caecal diverticulum on the anti-mesenteric side of the caudal end of the medial intestine, around the fifth week of gestation. The appendix does not elongate as rapidly as the rest of the colon. After rotation and descent, the base of the appendix is located at the posteromedial wall of the caecum about 2.5 cm below the ileocaecal valve, but this descent finishes after childhood. The variability of its descent and rotation leads to multiple possible final positions of the appendix4. The infant caecum is located in the right iliac fossa in about 55% of individuals (15.2). The blood supply of the caecum and appendix is the appendiceal branch of the ileocolic artery, which passes behind the terminal ileum. The arterial supply is terminal, so that thrombosis leads to rapid necrosis (15.3). The malpositioned appendix may give rise to signs of inflammation in unusual locations, that make diagnosis difficult.

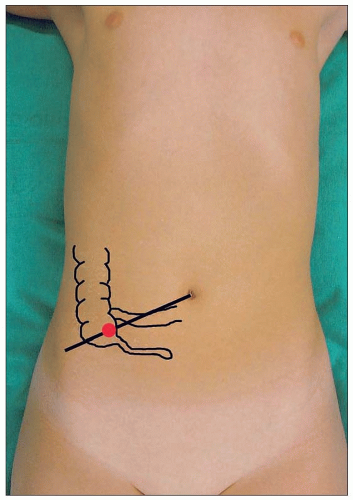

15.1 McBurney’s point is located two-thirds of the distance from the umbilicus to the anterior superior iliac spine. |

15.2 Possible positions of the appendix and their relative frequency4. |

Pathophysiology

Obstruction is a fundamental factor in the development of acute appendicitis. Obstruction increases intraluminal pressure leading to ischaemia, bacterial invasion, bacterial overgrowth, necrosis, and perforation.

In the early phases, activation of receptors in the intestinal wall leads to perception of pain in the periumbilical region. In later phases, when the purulent secretion from the appendiceal wall contacts the parietal peritoneum, somatic pain fibres are triggered and the pain localizes near the appendiceal site, McBurney’s point. The characteristic organisms responsible of appendiceal inflammation are predominantly anaerobic, including Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, Bacterioides fragilis, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, and Clostridium5.

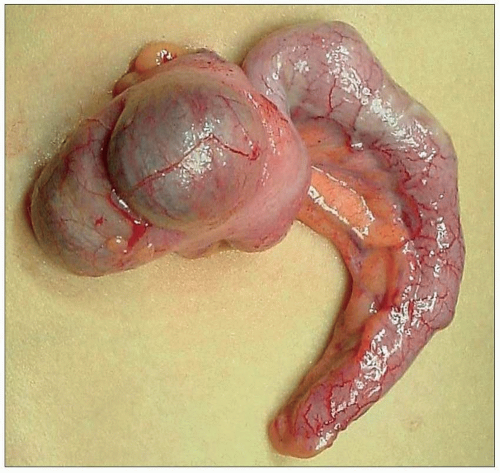

Many terms have been used to describe the pathologic stages of appendicitis, from the normal state to perforation. Only the clinically relevant distinctions of simple appendicitis (15.4) and complicated appendicitis should be made.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of appendicitis should be based on a careful history and physical examination. The paediatric surgeon may expect to make the accurate diagnosis in 80-90% of cases. White blood count (WBC) and imaging rarely add significant information.

Acute appendicitis typically occurs in older children. The incidence of appendicitis gradually increases from age 1 year onwards, peaking at around age 11-12 years. Although appendicitis is uncommon in infants, this age group has a high rate of complications because of delayed diagnosis. Difficulties of diagnosis may arise with patients younger than 2 years, and with preadolescent obese girls. In these two patient categories, analytical and imaging studies can provide additional information.

Clinical presentation

The classic sequence (persistent abdominal pain, fever, and localized pain on palpation at McBurney’s point) starts with periumbilical pain, preceded by appetite loss in about 50-60% of children. The main symptom is abdominal pain, usually beginning as a vague periumbilical pain or mild gastrointestinal discomfort. After several hours, this pain gradually migrates to the right iliac fossa. Characteristically the pain is implacable and is exacerbated by movements and pressure, making ambulation painful and difficult. A child with acute appendicitis typically walks bent over and slowly. Anorexia is a helpful sign. Nausea and vomiting appear after the onset of pain. If vomiting precedes abdominal pain, other diagnoses should be considered.

The last symptom in the clinical evolution is fever, which appears after pain and vomiting, and no more than 1°C above normal. Fever higher than 39°C is usually associated with complicated appendicitis (gangrenous and perforated). Symptoms may be influenced by the anatomical location of the appendix. Pain of a retrocaecal appendix may be in the flank or back. A pelvic appendix resting near the ureter or testicular vessels can cause urinary frequency, inguinal or testicular pain, or ureteral compression with hydronephrosis. Young patients aged 1-4 years, typically show vomiting and irritability, and draw up their legs to reduce pain. Other common manifestations include abdominal distension, diarrhoea, lethargy, and anorexia, together with fever. In 50% of cases an abdominal mass is detectable on palpation. The key point in this group of patients is vomiting.

Physical examination

Palpation should always be first superficial and then deep. The palpation should start in an area without pain, and the patient’s face should be watched for signs of discomfort. In fact the important thing to look for during examination is any localized area of abdominal pain. Abdominal tenderness is the most constant physical finding. The point of maximal tenderness is localized at McBurney’s point. Associated with tenderness progressively are abdominal muscle spasms. Rebound tenderness or Blumberg’s sign (i.e. pain felt on sudden release of steady pressure in the right iliac fossa region) reflects irritation of the parietal peritoneum of the inflamed appendix, and associated fluid secretion.

The routine use of rectal examination is controversial. Invariably this exploration causes discomfort to children, and pain during examination is not specific to appendicitis. It may be useful for detection of possible pelvic abscess or ovarian pathology.

Laboratory tests

WBC is of limited diagnostic value. Typically leukocyte count is mildly elevated, 10,000-16,000/mm3, with increased polymorphonuclear leukocytes, neutrophils, and immature neutrophils. 20% of patients with acute appendicitis will have a normal WBC. Very high WBC suggests perforation or another diagnosis.

Neutrophilia is more decisive for diagnosis than leukocytosis. In doubtful cases it is useful to monitor WBCs, as long as the patient is not receiving antibiotics. Urine sediment analyses are useful for detecting patients requiring fluid resuscitation and diseases of the urinary tract. The specific gravity and ketones are elevated. If the appendix is located adjacent to the ureter or the bladder, the red blood count and WBC in urine may be elevated.

Diagnostic imaging

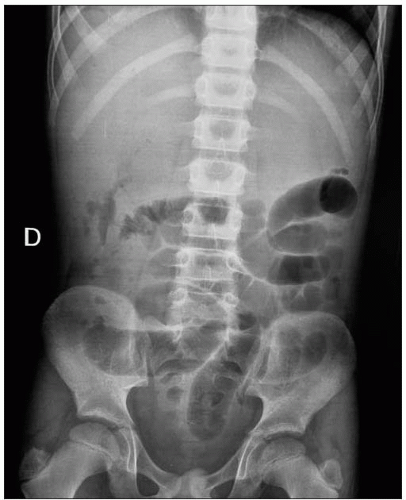

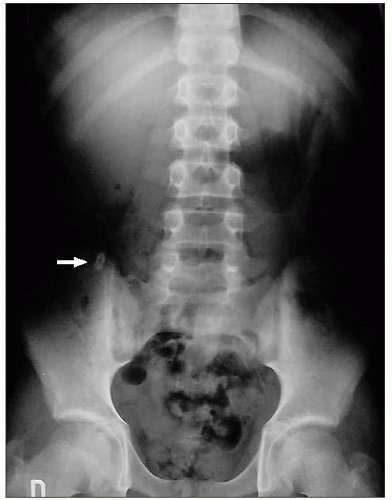

Imaging studies rarely add significant information in cases of classic appendicitis, and should be reserved for equivocal cases and when patient observation is indicated. Plain film, although it has a lower sensitivity and specificity, remains useful for detecting secondary problems associated with inflammation (Table 15.1) (15.5). The presence of faecalith is highly suggestive of acute appendicitis; however, faecalith is observed only in 10-15% cases of confirmed appendicitis (15.6).

Ultrasonography has constituted a significant advance in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, based on its rapidity, noninvasiveness, sensitivity (85-90%), and specificity

(92-96%). It is of particular value in adolescent and prepubertal girls. It should be the first approach in doubtful cases. Reports of centres with skilled radiologist often recommended ultrasonography for all children with suspected appendicitis (15.7, 15.8)6.

(92-96%). It is of particular value in adolescent and prepubertal girls. It should be the first approach in doubtful cases. Reports of centres with skilled radiologist often recommended ultrasonography for all children with suspected appendicitis (15.7, 15.8)6.

Table 15.1 Abnormal signs usually found in plain film in acute appendicitis | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

15.5 Upright film showing multiple air-fluid levels in the small bowel and absence of gas in the colon, typical of bowel obstruction. |

15.6 Simple radiography of the abdomen in a patient with acute appendicitis, showing appendicolith in the right iliac fossa (arrow).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|