Fig. 34.1

Endoscopic appearance of gonococcal proctitis. Notice the mucopurulent discharge

Culture for N. gonorrhoeae requires a Thayer–Martin chocolate agar and remains the “gold standard” for diagnosis.

Antimicrobial treatment must consider not only drug resistance but co-pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis as well. Third-generation cephalosporins (single dose 125 mg ceftriaxone, intramuscularly) are considered first-line therapy. Based on susceptibility, sulfonamides, penicillin, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended for the treatment of gonorrhoeae in the United States due to resistance patterns.

Coinfection with C. trachomatis should be treated empirically with either doxycycline (100 mg BID for 7 days) or azithromycin (1 g in a single dose). Patients should also alert their sexual partners for evaluation and treatment, to prevent disease spread or continued reinfection.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) has become an increasingly common cause of proctitis in Western Europe and the United States, particularly among MSM (mainly in HIV-infected patients undertaking high-risk sexual activities).

LGV is caused by C. trachomatis serovars L1, L2, and L3.

LGV is primarily a disease of the lymphatics as infection extends from the primary inoculation site to the draining lymph nodes, producing a lymphangitis, with subsequent nodal necrosis and abscess formation.

The primary lesion of LGV occurs at the site of inoculation 3–30 days after sexual contact in the form of a painless pustule, shallow ulcer, or erosion. A secondary stage can occur 3–6 months after exposure and manifests as acute proctitis and inguinal lymphadenopathy that can suppurate and ulcerate.

Excruciating pain helps to distinguish it from many other forms of proctitis.

Lymphedema and genital elephantiasis, with persistent suppuration and pyoderma, can also be seen.

The anal findings include ulcers, fistulas, and strictures, which, along with endoscopic findings, closely resemble Crohn’s disease.

Specific LGV-associated serovars of chlamydia can be detected in those with positive PCR by genotyping.

Diagnosis is usually initially based on clinical findings in association with a positive rectal chlamydia culture as genotyping results are not readily or immediately available.

The preferred treatment is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks, with erythromycin used as an alternative.

Syphilis

Treponema pallidum is a spirochete that invades subcutaneous tissues through abrasions caused during sexual intercourse.

A painless ulcer (chancre) forms and then the draining lymph nodes (Figs. 34.2 and 34.3).

Fig. 34.2

Painless posterior-lateral ulceration (chancre) of anal syphilis

Fig. 34.3

Suppurative inguinal lymphadenopathy of syphilis

Widespread dissemination of spirochetes occurs early leading to subsequent clinical manifestations of secondary or tertiary syphilis in untreated patients.

Weeks to a few months later, approximately 25 % of individuals with untreated infection develop a systemic illness that represents secondary syphilis, with symptoms including a rash on the palms, soles, and mucosal surfaces; fever; headache; malaise; anorexia; and diffuse lymphadenopathy.

Untreated patients are at risk for the manifestations of late or tertiary syphilis, including central nervous system, cardiovascular, and gummatous syphilis. Condylomata lata occurring in the perianal region appear as moist wartlike lesions that may be confused for human papilloma virus infection.

Serologic testing is the mainstay of diagnosis, traditionally involving a nonspecific nontreponemal antibody test followed by a more specific treponemal test for diagnostic confirmation.

Long-acting penicillin preparations are the preferred drugs for the treatment of all stages of syphilis. A single dose of benzathine penicillin G (2.4 million units intramuscularly) remains the standard therapy for primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis.

Late latent syphilis or latent syphilis of unknown duration requires three doses of 2.4 million units intramuscularly each at 1-week intervals.

Options for the treatment of syphilis in penicillin allergic patients include tetracyclines, macrolides, or ceftriaxone.

Brucellosis

Brucellosis is a bacterium that is transmitted through unpasteurized goats’ milk or cheese, contact with infected animals, or inhalation of aerosols.

The constellation of symptoms is similar to the flu and may include fever, sweats, headaches, back pains, and weakness. Symptoms are that of a nonspecific colitis.

Cultures of the exudate will reveal the organism and are required for confirmation.

Endoscopic examination reveals nonspecific inflammatory changes.

Serologic tests are available to aid in early diagnosis and installation of treatment.

Single-agent therapy has an unacceptably high relapse rate so that currently, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 3–6 weeks and streptomycin 1 g IM q 12–24 h for 14 days are preferred. A more recent meta-analysis suggests that triple therapy by adding an aminoglycoside may result in lower failure rates.

Actinomycosis

Actinomycosis is an uncommon, chronic granulomatous disease caused by Actinomyces israelii, an anaerobic gram-positive bacterium.

Infection in the cervicofacial area is most common (~50 %), but abdominal actinomycosis typically involves the appendix and ileocecal region.

It may mimic more common conditions such as malignancy, Crohn’s disease, and tuberculosis.

Colonoscopic findings can include thickened appearing mucosa, colitis, ulceration, nodularity, and a button-like elevation of an inverted appendiceal orifice.

Diagnosis is confirmed upon histological identification of characteristic yellow sulfur granules and/or culture of A. israelii.

Medical treatment consists of a prolonged course of penicillin, intravenously for 4–6 weeks, followed by oral therapy for 6–12 months to prevent relapse.

Surgical options are most often for disease complications such as resection of an obstructive segment or abscess drainage, which occur most often prior to a confirmative diagnosis.

Viral Enteritis/Colitis

Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a member of the herpes virus family and is considered an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised hosts.

Infection typically occurs late in the course of HIV infection when CD4 cell counts plummet or in immunosuppressed transplant patients.

Involvement is most common in the colon, although concomitant disease may occur in the proximal gastrointestinal tract.

The clinical manifestations of CMV colitis vary greatly, from asymptomatic carriers to fulminate life-threatening infections. Symptoms include fever, weight loss, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, which may be bloody. As the disease progresses, frank ulceration, toxic megacolon, and perforation may occur.

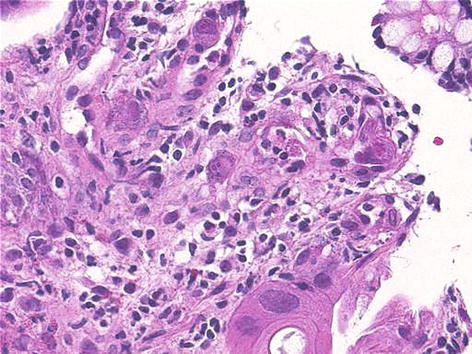

Biopsies should be obtained for histopathologic examination to evaluate for the characteristic inclusion bodies (Fig. 34.4).

Fig. 34.4

Cytomegalovirus colitis. Infected cells are enlarged with eosinophilic intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions (Courtesy of Jeanette R. Burgess, MD)

Currently, there are several agents available for the systemic therapy of CMV infection, including ganciclovir, valganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir. Surgical therapy is generally relegated to complications such as bleeding and perforation, where a subtotal colectomy with ileostomy is often required.

Herpes Simplex Virus Proctitis

Most colorectal infections are as a result of herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2. HSV 1 is not common, accounting for 13 % of rectal HSV infections, though most likely represents oroanal transmission. Patients are more commonly HIV positive.

Presenting symptoms include anorectal pain, discharge, tenesmus, and rectal bleeding as well as difficulty in urinating, temporary impotence, fecal incontinence, and sacral paresthesias.

The diagnosis is established by a suggestive history and physical examination findings including herpetic vesicles, pustules, and ulcerations that affect the perianal skin and anal canal.

Sigmoidoscopic exam demonstrates an acute proctitis.

Laboratory evaluation of rectal samples allows the virus to be isolated by culture. A variety of immunoassays currently exist to aid in diagnosis.

Oral acyclovir has been demonstrated to be effective in alleviating symptoms although other formulations may allow for twice or once daily dosing regimens. Immunocompromised patients should be treated with intravenous acyclovir followed by chronic suppressive therapy.

Parasitic Enteritis/Colitis

Amebiasis

Entamoeba histolytica is highly prevalent worldwide with approximately 40–50 million cases annually, accounting for 40,000 deaths.

This protozoan exists in either the cyst or trophozoite stages. Cysts are ingested in contaminated food or water, or via fecal-oral sexual transmission, and become trophozoites in the small intestine. Upon reaching the colon, they adhere to a specific lectin on the epithelial cell and penetrate the mucosa causing colitis and bloody diarrhea.

Approximately 90 % of E. histolytica infections are asymptomatic, with invasive disease depending on host genetic susceptibility, age, and immunocompetence.

Symptoms range from mild diarrhea to severe dysentery. Cases of fulminant colitis with bowel necrosis, perforation, and peritonitis occur in ~0.5 % but are associated with a mortality rate of more than 40 %.

Localized colonic infection may also occur that results in a mass of granulation tissue, or an ameboma.

The diagnosis can be aided via antigen testing or serology tests.

Colonoscopy classically demonstrates characteristic flask-shaped amebic ulcers and scrapings or biopsy specimens can be taken.

Treatment consists of oral metronidazole.

Balantidiasis

Balantidium coli is the largest and least common protozoal pathogen affecting humans and is the only ciliate that produces important human disease.

B. coli infection is spread to humans by ingestion of cysts spread by contaminated water and food.

The trophozoite invades the distal ileal and colonic mucosa to produce intense mucosal inflammation and ulceration.

Diarrhea with blood and mucus is accompanied by nausea, abdominal discomfort, and weight loss is common.

It can develop into fatal fulminant colitis with peritonitis and colonic perforation.

The diagnosis is made by the identification of trophozoites excreted in the stool or from the margin of rectal ulcers associated with infection.

The most commonly used treatment is tetracycline 500 mg four times daily for 10 days.

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidium is an intracellular protozoan parasite that infects and the epithelial cells of the digestive or respiratory tracts, causing a secretory diarrhea that can be associated with malabsorption, and biliary tract disease (i.e., stricturing and cholangitis).

Cryptosporidiosis presents in one of three main settings: (1) sporadic, often water-related outbreaks of self-limited diarrhea in immunocompetent hosts; (2) chronic, life-threatening illness in immunocompromised patients (i.e., HIV infection); and (3) diarrhea with malnutrition in young children in developing countries.

Transmission of Cryptosporidium occurs via spread from an infected person or animal or from a fecal-contaminated food or water source.

The pathogenesis of Cryptosporidium infection involves ingestion of oocysts, excyst to sporozoites in the small bowel lumen, and invasion of the epithelial cells.

Clinically, this may result in an asymptomatic carrier state, mild diarrhea, or severe enteritis.

The illness usually resolves without therapy in 10–14 days in immunologically healthy people, yet excretion of oocysts can continue for prolonged periods.

In immunocompromised AIDS patients, a number of other clinical manifestations have been described, including cholecystitis, cholangitis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, and respiratory tract involvement. Biliary tract involvement most commonly with acalculous cholecystitis or sclerosing cholangitis affects 10–30 % of these patients with underlying AIDS.

The diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis is made by microscopic identification of the oocysts in stool or tissue, via microscopy, histopathology, ELISA, and PCR.

Immunocompetent hosts generally recover within 2 weeks without antimicrobial therapy, only requiring simple supportive treatment. Treatment with nitazoxanide has been shown to speed clinical improvement and clear posttreatment Cryptosporidium oocysts from stool samples.

For HIV-infected patients, it is essential to initiate appropriate HAART treatment. In addition, nitazoxanide is recommended when CD4 counts are less than 100 cells/μL.

Giardiasis

Giardia lamblia is a flagellated protozoan gastrointestinal parasite that is commonly encountered in the United States.

This is a common cause of water-borne and food-borne diarrhea encountered in day-care center outbreaks, internationally adopted children, and diarrhea in international travelers.

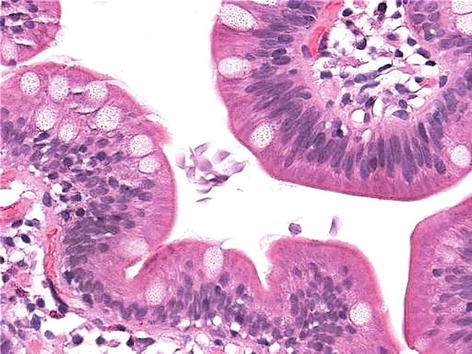

Ingested Giardia cysts excyst in the upper small bowel and release trophozoites which absorb to the mucosal surface of the jejunum but do not invade the epithelium (Fig. 34.5).

Fig. 34.5

Duodenal giardiasis. Pale pink organisms are identified in the lumen. No architectural distortion or inflammation is seen (Courtesy of Jeanette R. Burgess, MD)

The mechanism how this leads to diarrhea and malabsorption is poorly understood.

Transmission occurs via person-to-person (infectious cysts in stool), in uncooked foods, and contaminated water supplies (common in hikers and bikers who drink from mountain lakes).

The clinical presentation of infection varies greatly, ranging from asymptomatic infection in up to 60 % to a self-limited acute or long-lasting chronic infection.

Classic symptoms of an acute infection include a prolonged 2-to-4-week course of diarrhea along with weight loss.

Chronic infection can occur in up to 30–50 % of symptomatic patients, resulting in loose stools, significant malabsorption, weight loss, and fatigue.

Proper identification involves stool samples for ova and parasite (O and P), which reveals trophozoites and cysts in 50–70 % of cases with a single specimen and approximately 90 % after three specimens.

Immunoassays with antibodies directed against either cyst or trophozoite antigens can confirm the diagnosis.

Symptomatic patients are given antimicrobial therapy with metronidazole as the first-line therapy.

Trypanosomiasis

Trypanosoma cruzi is the organism responsible for Chagas’ disease or trypanosomiasis.

Chagas’ disease is transmitted via the bite of the reduviid bug, also known as the “kissing bug.”

Clinical syndromes present in two stages – acute and chronic. Most patients infected with T. cruzi are asymptomatic during the acute stage of infection, while others develop a wide range of symptoms including fever, swollen face or eyelids (Romana’s sign), peripheral edema, conjunctivitis, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and less commonly, myocarditis and meningoencephalitis.

Organ damage during the acute phase is due to both high-grade parasitemia and direct tissue parasitism.

Approximately 50 % of infected individuals develop chronic disease leading to cardiomyopathy, megaesophagus, and megacolon.

All patients with acute infection and all immunosuppressed individuals should be treated with either nifurtimox or benznidazole.

Ascariasis

Ascaris lumbricoides is one of the most common helminthic human infections worldwide. Transmission typically occurs via ingestion of contaminated water or food. The life cycle entails the ova hatching in the small intestine and releasing larvae, which penetrate the intestinal wall and migrate hematogenously or via lymphatics.

The mature worms are generally found in the jejunum, although they can live anywhere from esophagus to rectum.

Adult worms live 1–2 years, and one person can carry anywhere from 100 to 1,000 worms, depending on egg exposure.

Although most patients are asymptomatic, large worm loads are responsible for the development of symptoms, primarily obstruction.

Additionally, symptoms have been attributed to the immunologic response to the foreign body.

Diagnosis is typically made by stool microscopy.

The mainstays for treatment are mebendazole and albendazole, typically administered as a single dose.

Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis is caused by infection with parasitic blood flukes/trematode known as schistosomes.

Their life cycle is complex, beginning with infection via contaminated fresh water and subsequent hematogenous spread, where they survive for many years.

The eggs invade tissues, release toxins, and provoke an immune response. In the bowel, granulomatous inflammation around the invading eggs can result in intestinal schistosomiasis characterized by ulceration and scarring.

Regarding intestinal schistosomiasis, most patients present with intermittent abdominal pain, poor appetite, and diarrhea. Intestinal polyps, ulcers, and strictures can also arise due to granulomatous inflammation surrounding eggs that are deposited in the bowel wall.

The diagnosis is made by microscopy with egg identification, serology radiological findings in the appropriate clinical scenario.

All infected patients should be treated, regardless of symptomatology, as the adult worms can live for years. Praziquantel paralyzes worms by altering permeability of calcium channels, causing the worms dislodge from the intestines, and are ultimately passed by peristalsis.

Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloides stercoralis infection results in a wide range of clinical presentations, from a peripheral eosinophilia to septic shock, depending on host immune status.

Contact with contaminated soil allows the filariform larvae to penetrate the skin and spread hematogenously to the lungs, where they penetrate the alveolae, travel up the tracheobronchial tree, and are swallowed, similar to Ascaris.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree