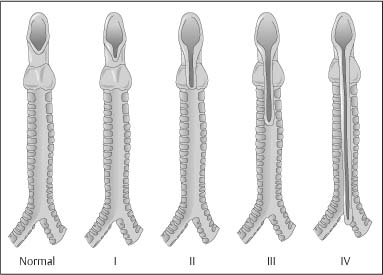

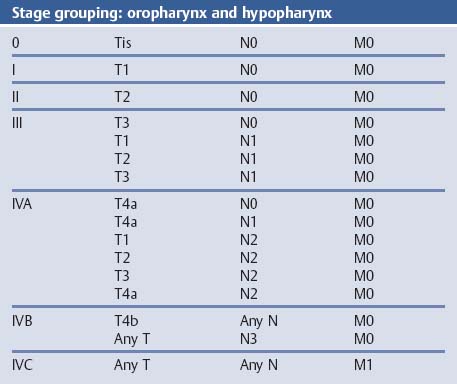

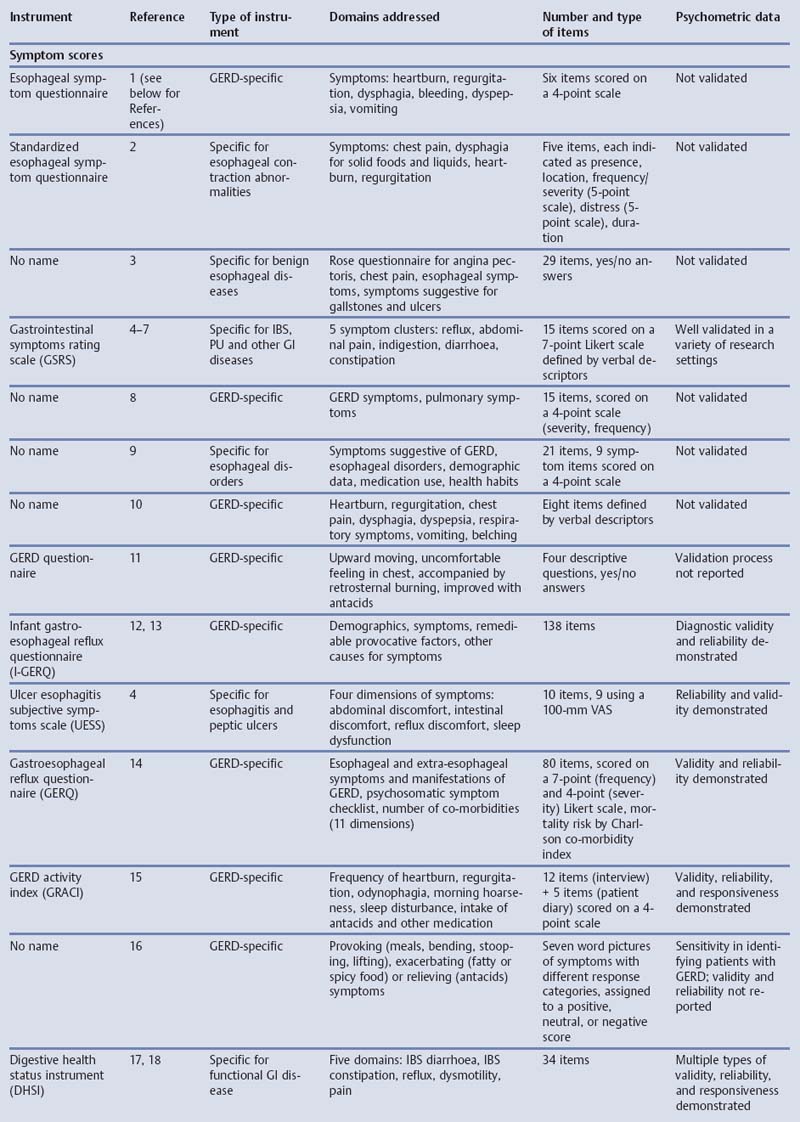

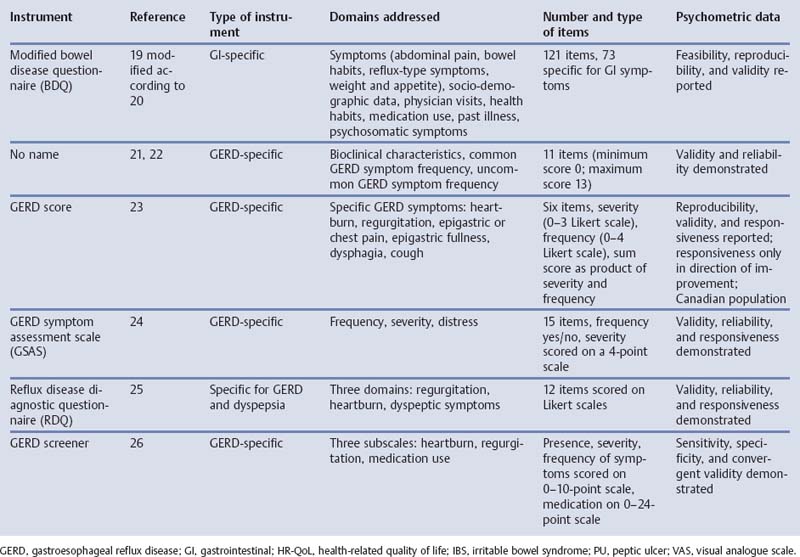

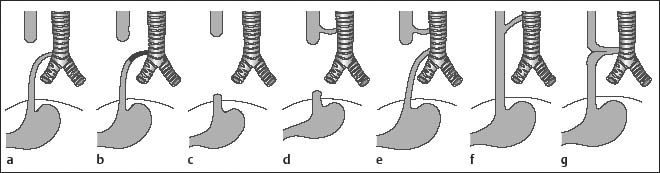

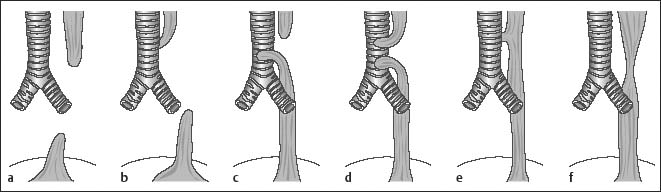

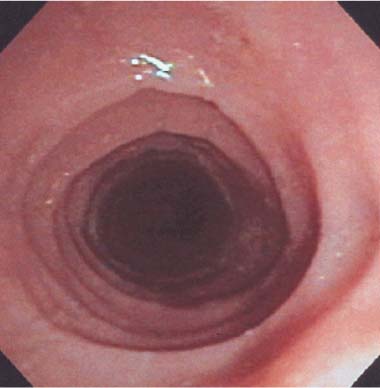

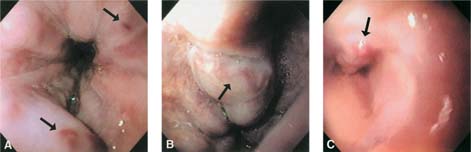

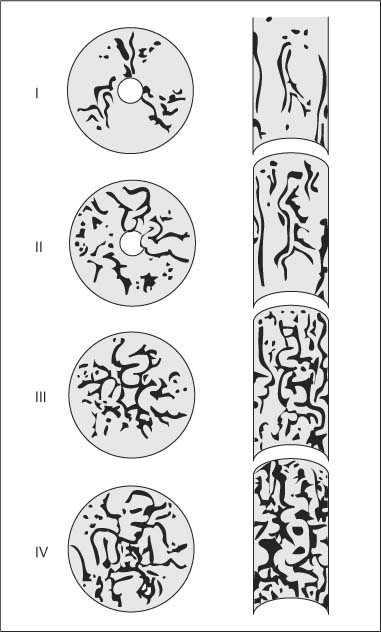

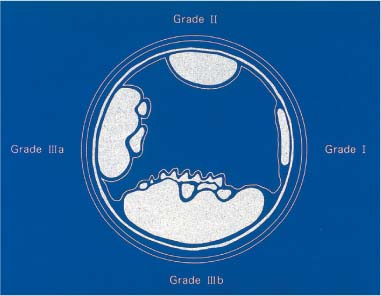

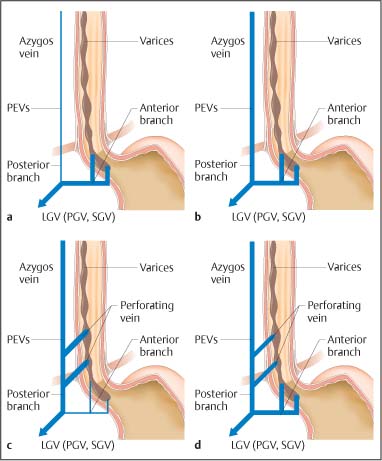

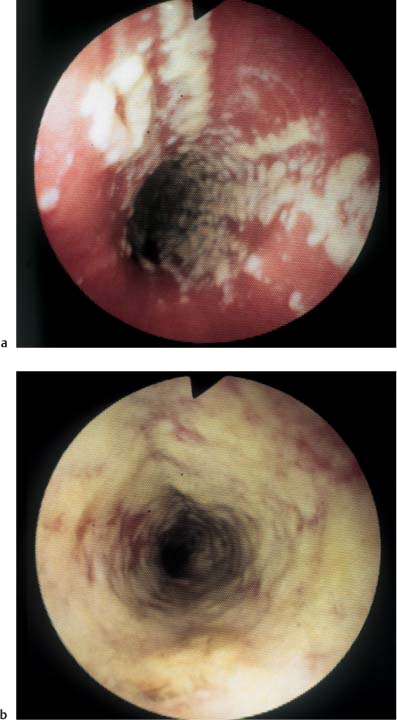

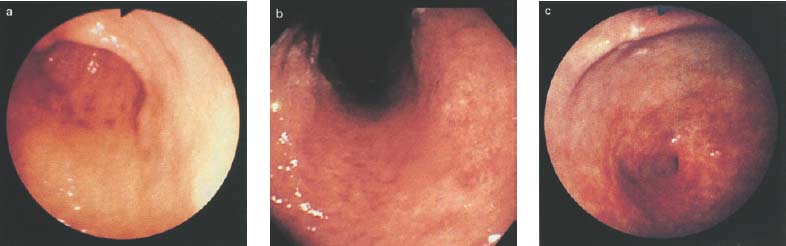

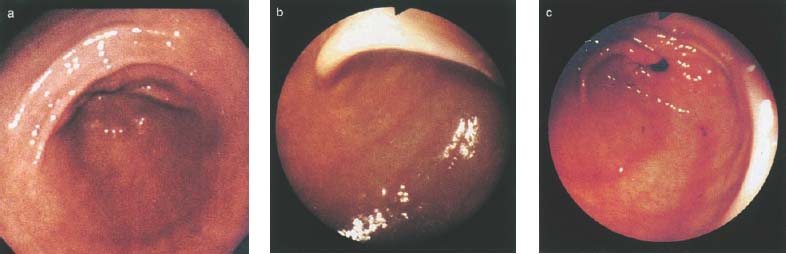

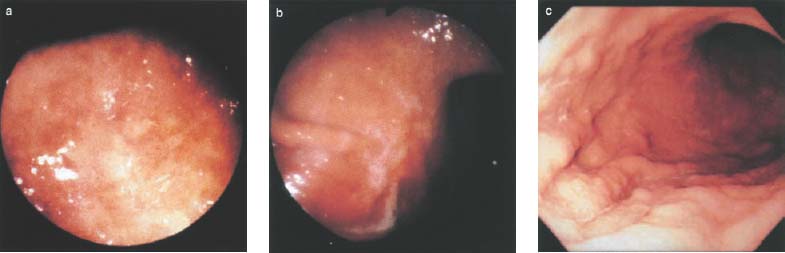

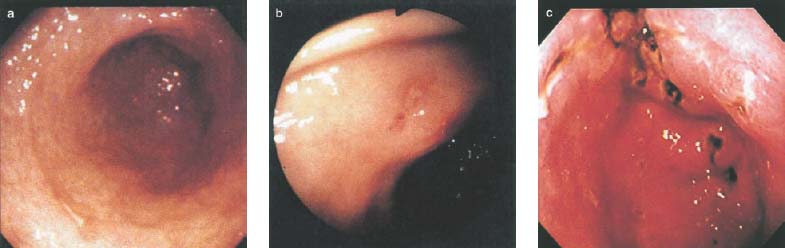

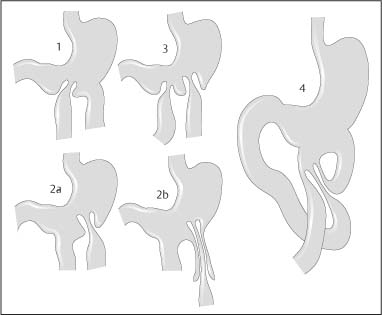

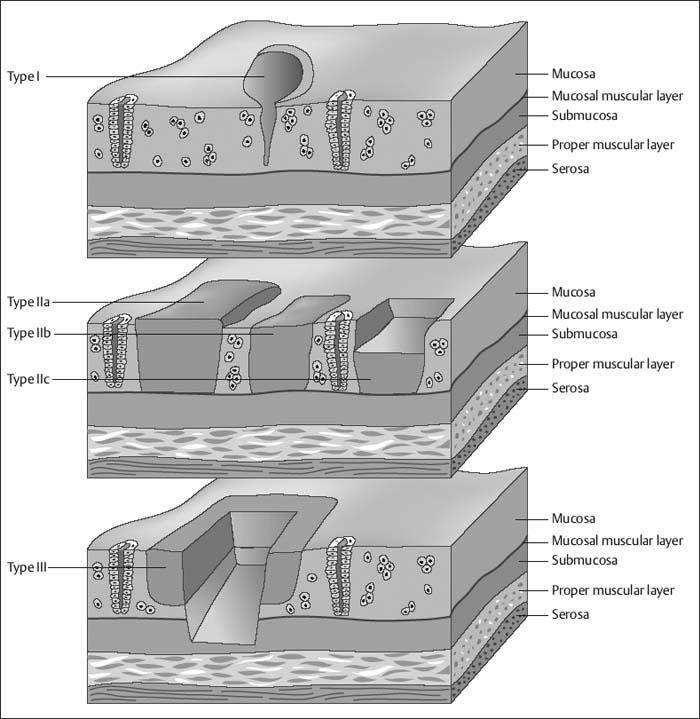

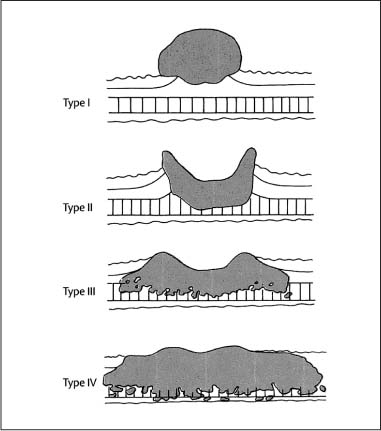

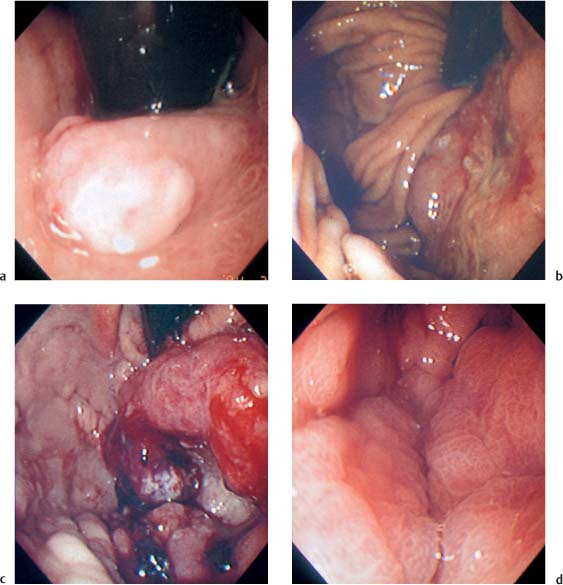

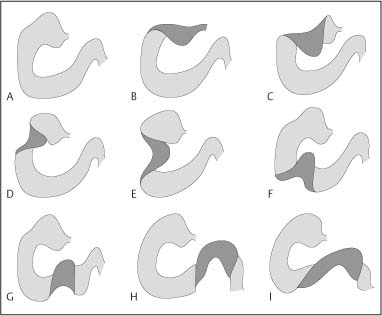

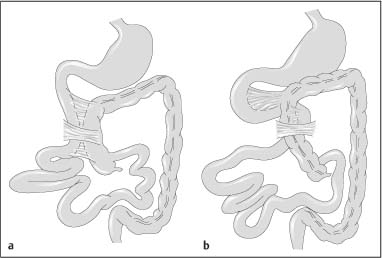

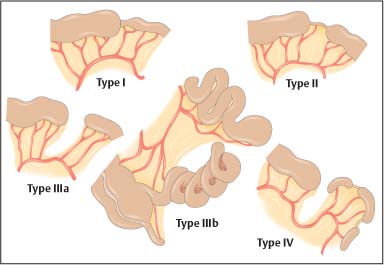

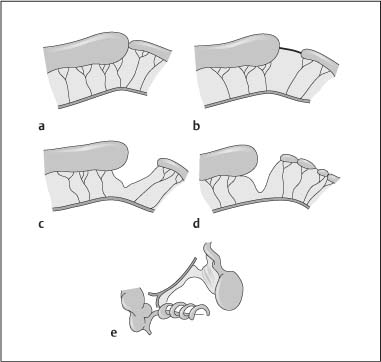

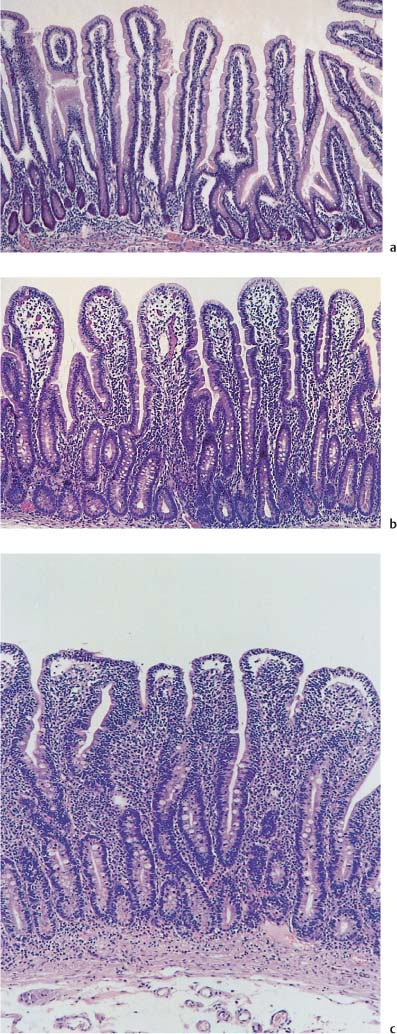

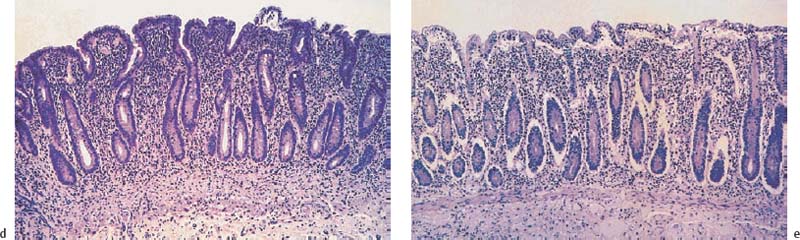

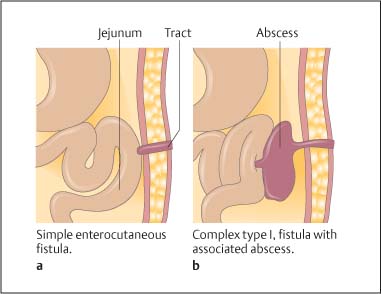

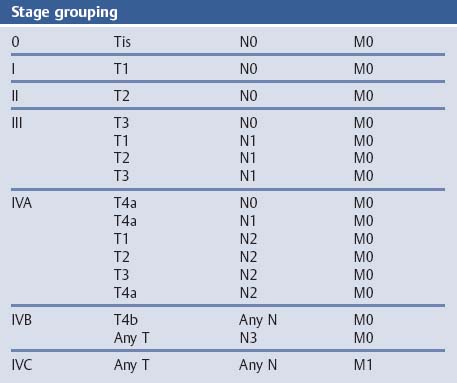

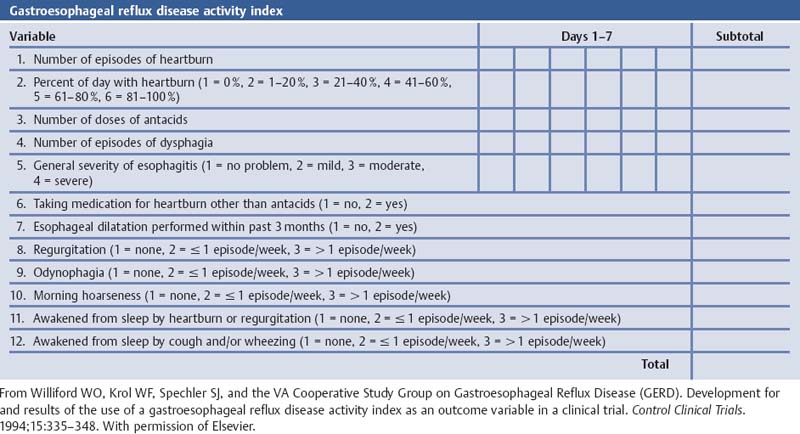

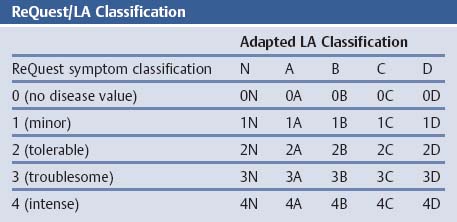

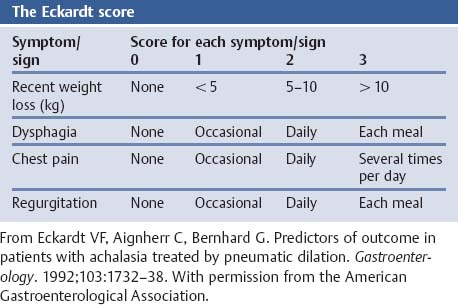

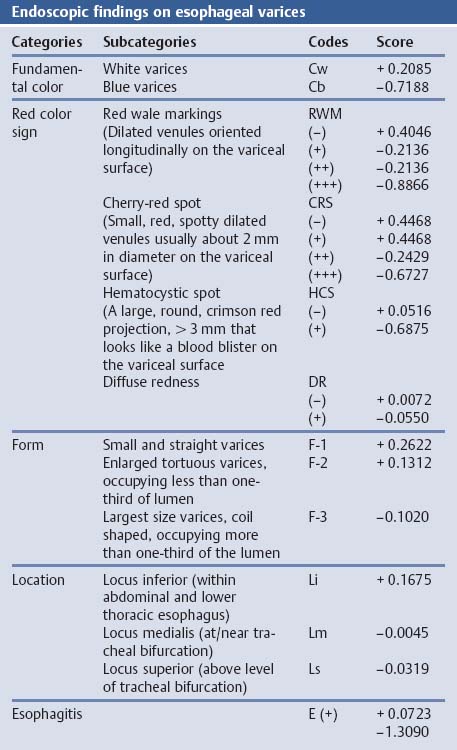

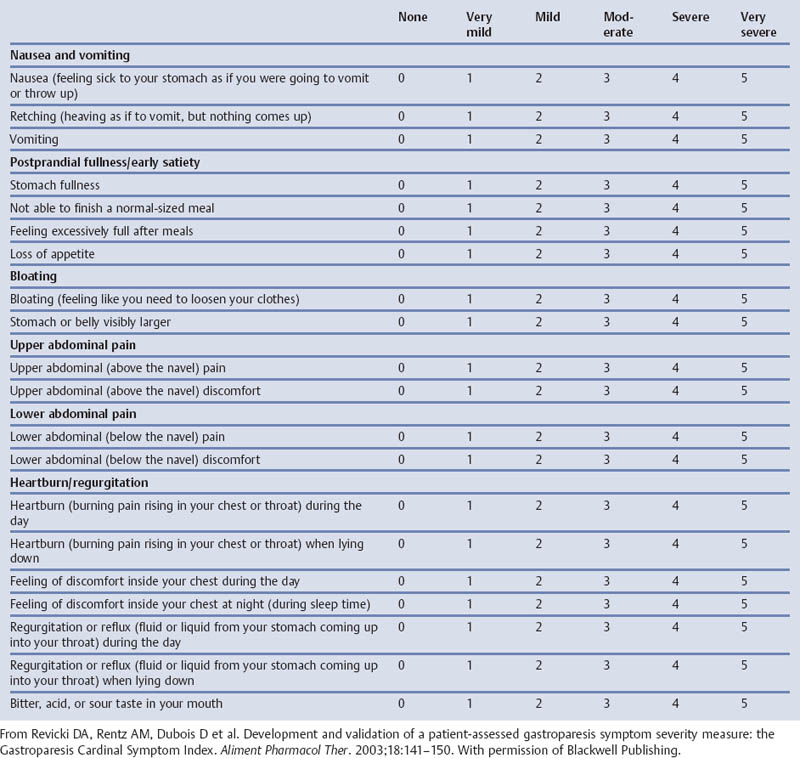

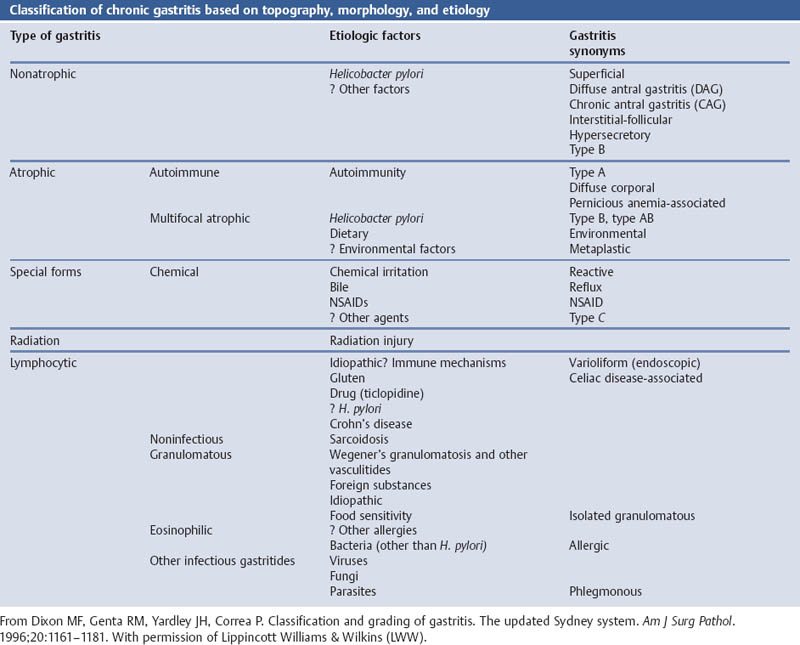

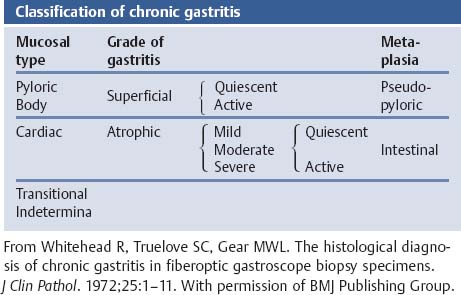

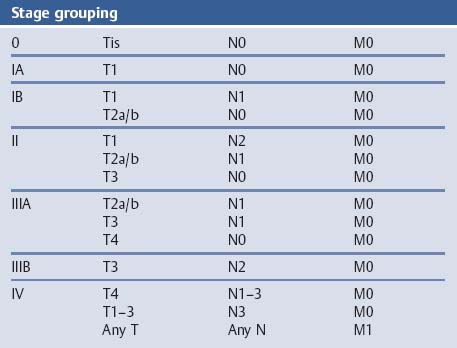

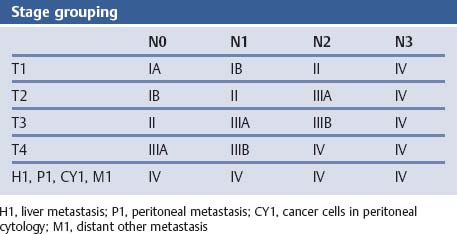

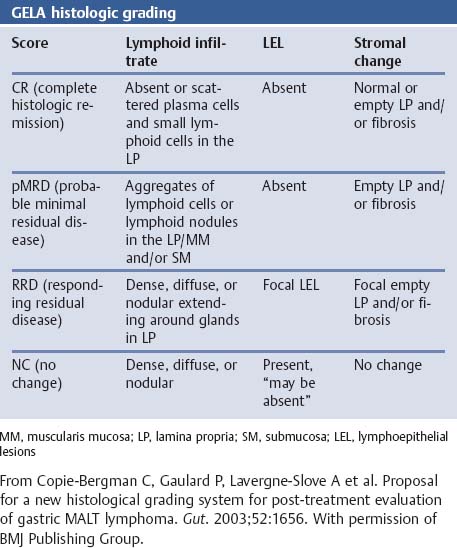

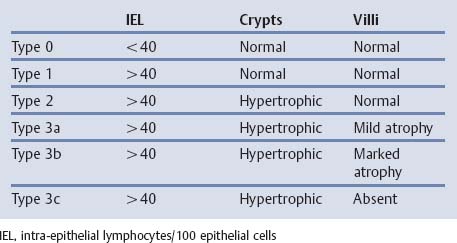

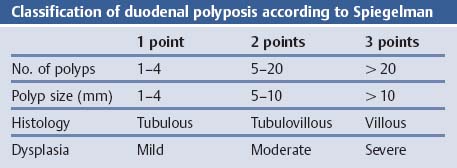

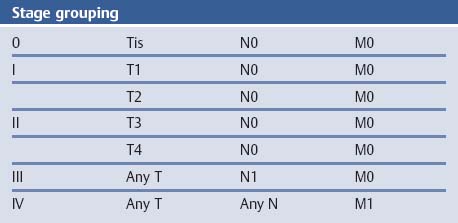

Chapter 2 Organ-Related Staging and Grading The original classification of laryngotracheal-esophageal clefts is divided into three types depending on the extent of tracheal involvement (for Type IV see Comments below). Type I Cleft involves the larynx, inter-arytenoid muscles, and the cricoid laminae Type II Extends beyond the cricoid lamina up to the cervical trachea (sixth tracheal ring) Type III Involves the trachea including the carina Type IV Cleft extending beyond the carina into either one or both main stem bronchi From Ryan DP, Muehrcke DD, Doody DP. Laryngotracheoesophageal cleft (type IV): Management and repair of lesions beyond the carina. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:962–970. With permission of Elsevier. Ryan et al. added type IV in 1991. They described three cases of laryngotracheal-esophageal clefts extending into the bronchi. Pettersson G. Laryngotracheal esophageal cleft. Z Kinderchir. 1969;7:43–49. Ryan DP, Muehrcke DD, Doody DP. Laryngotracheoesophageal cleft (type IV): Management and repair of lesions beyond the carina. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:962–970. To modify Pettersson’s classification of laryngotracheal-esophageal clefts to allow a more precise definition of the milder cases in which surgery carries a reasonable prognosis. Type 1 Limited to cricoid cartilage: 1A Inter-arytenoid cleft, extending to, but not into the superior aspect of the cricoid cartilage; 1B Cleft extends partially through the cricoid; 1C Cleft extends completely through the cricoid Type 2 Cleft includes the proximal 3 cm of the tracheoesophageal septum Type 3 Involves the trachea including the carina Type 4 Cleft involves the entire tracheoesophageal septum From Pettersson G. Inhibited separation of larynx and the upper part of trachea from oesophagus in a newborn; report of a case successfully operated upon. Acta Chir Scand. 1955;110:250–254. By permission of Taylor & Francis AS. Armitage EN. Laryngotracheo-esophageal cleft. A report of three cases. Anaesthesia. 1984;39:706–713. Pettersson G. Inhibited separation of larynx and the upper part of trachea from oesophagus in a newborn; report of a case successfully operated upon. Acta Chir Scand. 1955;110: 250–254. To review the clinical features, associated congenital abnormalities, management, and morbidity of infants presenting with posterior laryngeal and laryngotracheal clefts. Type I 31% Clefts are limited to the inter-arytenoid region above the vocal folds. This type does not involve the cricoid cartilage Type II 47% This type includes the cricoid and extends into the cervical trachea Type III 22% This type involves the thoracic trachea From Evans JNG. Management of the cleft larynx and tracheoesophageal clefts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985;94:627–630. With permission of Annals Publishing Co. Treatment is conservative, via primary endoscopic surgical repair or primary repair via an anterior laryngofissure. Gastroesophageal reflux is controlled by fundoplication. Evans JNG. Management of the cleft larynx and tracheoesophageal clefts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985;94: 627–630. Benjamin and Inglis and Dubois proposed a classification of laryngeal clefts with four main types. Type I Cleft is limited to the supraglottic lumen above the vocal folds Type II A partial cleft of the cricoid extending below the level of the vocal folds Type III Involves the whole cricoid cartilage and may extend to the cervical TE septum Type IV Involves a major part of the TE wall in the thorax From Benjamin B, Inglis A. Minor congenital laryngeal clefts: diagnosis and classification. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989;98:417–420. With permission of Annals Publishing Co. Type I Cleft extends down to, but does not involve, the superior portion of the posterior cricoid plane Type II Cleft extends into and at times as far down as the inferior aspect of the posterior cricoid plane Type III Cleft extends into the cervical trachea to a variable distance Type IV Cleft extends into the thoracic trachea and may reach the carina or even beyond to involve one or both main-stem bronchi From DuBois JJ, Pokorny WJ, Harberg FJ, Smith RJ. Current management of laryngeal and laryngotracheoesophageal clefts. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:855–860. With permission of Elsevier Inc. To propose a screening instrument for oral problems in the elderly for referral and further evaluation. Score D Dry mouth 2 E Eating difficulty 1 N No dental care within past two years 1 T Tooth loss 2 A Alternative food selection because of masticatory problems 1 L Lesions, scores, or lumps in mouth 1 From Bush LA, Horenkamp N, Morley JE, Spiro A 3rd. D-E-N-T-A-L: A rapid self-administered screening instrument to promote referrals for further evaluation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:979–481. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. Fig. 2.1 Laryngotracheal-esophageal clefts: grading according to Benjamin and Inglis and according to Dubois. The cleft larynx is a rare congenital anomaly. Type II–IV require urgent airway management. Dubois classified laryngotrachealesophageal clefts on an embryological basis. Benjamin B, Inglis A. Minor congenital laryngeal clefts: diagnosis and classification. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989; 98:417–420. DuBois JJ, Pokorny WJ, Harberg FJ, Smith RJ. Current management of laryngeal and laryngotracheoesophageal clefts. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:855–860. This score can be used to identify potential oral problems. Bush LA, Horenkamp N, Morley JE, Spiro A 3rd. D-E-N-T-A-L: A rapid self-administered screening instrument to promote referrals for further evaluation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:979–481. Thompson WM, Brown RH, Williams SM. Dentures, prosthetic treatment needs, and mucosal health in an institutionalized elderly population. N Z Dent J. 1992;88:51. Dental and periodontal lesions in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease are graded. Rating Erosion severity Grade 0 No superficial enamel modification Grade 1 Loss of superficial enamel features without reaching dentin Grade 2 Dentin exposure less than 1/3 of surface Grade 3 Dentin exposure more than 1/3 of surface From Eccles JD, Jenkins WG. Dental erosion and diet. J Dent. 1974;2: 153–159. With permission of Elsevier. TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed T0 No evidence of primary tumor Tis Carcinoma in situ T1 Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension T2 Tumor more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest dimension T3 Tumor more than 4 cm in greatest dimension T4a Tumor invades the larynx, deep/extrinsic muscle of tongue, medial pterygoid, hard palate, or mandible T4b Tumor invades lateral pterygoid muscle, pterygoid plates, lateral nasopharynx, or skull base or encases carotid artery T1 Tumor limited to one subsite of hypopharynx and 2 cm or less in greatest dimension T2 Tumor invades more than one subsite of hypopharynx or an adjacent site, or measures more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest diameter without fixation of hemilarynx T3 Tumor measures more than 4 cm in greatest dimension or with fixation of hemilarynx T4a Tumor invades thyroid/cricoid cartilage, hyoid bone, thyroid gland, esophagus or central compartment soft tissue T4b Tumor invades prevertebral fascia, encases carotid artery, or involves mediastinal structures Specificity is limited, especially with associated dental decay. The superficial effects of reflux on enamel are difficult to recognize. Only grade II and III can be seen with a retro mirror. Eccles JD, Jenkins WG. Dental erosion and diet. J Dent. 1974;2: 153–159. NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed N0 No regional lymph node metastasis N1 Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less in greatest dimension N2 Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension, or multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension, or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension N2a Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension N2b Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension N2c Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension N3 Metastasis in a lymph node more than 6 cm in greatest dimension MX Presence of distant metastasis cannot be assessed M0 No distant metastasis M1 Distant metastasis GX Grade cannot be assessed G1 Well differentiated G2 Moderately differentiated G3 Poorly differentiated RX Presence of residual tumor cannot be assessed R0 No residual tumor R1 Microscopic residual tumor R2 Macroscopic residual tumor From Greene, FL, Page, DL, Fleming ID et al. Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed (2002) published by Springer-New York, www.springeronline.com. The AJCC TNM staging system uses three basic descriptors that are then grouped into stage categories. The first component is “T,” which describes the extent of the primary tumor. The next component is “N,” which describes the absence or presence and extent of regional lymph node metastasis. The third component is “M,” which describes the absence or presence of distant metastasis. The final stage groupings (determined by the different permutations of “T,” “N,” and “M”) range from Stage 0 through Stage IV. Greene, FL, Page, DL, Fleming ID et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer, 2002. http://www.cancerstaging.org/. TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed T0 No evidence of primary tumor Tis Carcinoma in situ T1 Tumor limited to one subsite of supraglottis with normal vocal cord mobility T2 Tumor invades mucosa of more than one adjacent subsite of supraglottis or glottis or region outside the supraglottis (e.g., mucosa of base of tongue, vallecula, medial wall of pyriform sinus) without fixation of the larynx T3 Tumor limited to larynx with vocal cord fixation and/or invades any of the following: postcricoid area, pre-epiglottic tissues, paraglottic space, and/or minor thyroid cartilage erosion (e.g., inner cortex) T4a Tumor invades through the thyroid cartilage and/or invades tissues beyond the larynx (e.g., trachea, soft tissues of neck including deep extrinsic muscle of the tongue, strap muscles, thyroid, or esophagus) T4b Tumor invades prevertebral space, encases carotid artery, or invades mediastinal structures T1 Tumor limited to the vocal cord(s) (may involve anterior or posterior commissure) with normal mobility T1a Tumor limited to one vocal cord T1b Tumor involves both vocal cords T2 Tumor extends to supraglottis and/or subglottis, or with impaired vocal cord mobility T3 Tumor limited to the larynx with vocal cord fixation, and/or invades paraglottic space, and/or minor thyroid cartilage erosion (e.g., inner cortex) T4a Tumor invades through the thyroid cartilage and/or invades tissues beyond the larynx (e.g., trachea, soft tissues of neck including deep extrinsic muscle of the tongue, strap muscles, thyroid, or esophagus) T4b Tumor invades prevertebral space, encases carotid artery, or invades mediastinal structures T1 Tumor limited to the subglottis T2 Tumor extends to vocal cord(s) with normal or impaired mobility T3 Tumor limited to larynx with vocal cord fixation T4a Tumor invades cricoid or thyroid cartilage and/or invades tissues beyond the larynx (e.g., trachea, soft tissues of neck including deep extrinsic muscles of the tongue, strap muscles, thyroid, or esophagus) T4b Tumor invades prevertebral space, encases carotid artery, or invades mediastinal structures NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed N0 No regional lymph node metastasis N1 Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less in greatest dimension N2 Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension, or multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension, or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension N2a Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node more than 3 cm but not more than 6 cm in greatest dimension N2b Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension N2c Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none more than 6 cm in greatest dimension N3 Metastasis in a lymph node more than 6 cm in greatest dimension MX Presence of distant metastasis cannot be assessed M0 No distant metastasis M1 Distant metastasis GX Grade cannot be assessed G1 Well differentiated G2 Moderately differentiated G3 Poorly differentiated RX Presence of residual tumor cannot be assessed R0 No residual tumor R1 Microscopic residual tumor R2 Macroscopic residual tumor From Greene, FL, Page, DL, Fleming ID et al. Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed (2002) published by Springer-New York, www.springeronline.com. The AJCC TNM staging system uses three basic descriptors that are then grouped into stage categories. The first component is “T,” which describes the extent of the primary tumor. The next component is “N,” which describes the absence or presence and extent of regional lymph node metastasis. The third component is “M,” which describes the absence or presence of distant metastasis. The final stage groupings (determined by the different permutations of “T,” “N,” and “M”) range from Stage 0 through Stage IV. Greene, FL, Page, DL, Fleming ID et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer, 2002. http://www.cancerstaging.org/. To design a reflux disease questionnaire for the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease that recognizes classic symptom patterns for reflux disease. The Carlsson–Dent Questionnaire is a self-administered questionnaire with seven items (heartburn, pain in the stomach, regurgitation, discomfort in the stomach, food sticking in the gullet after swallowing, feeling sick, and vomiting) that focus on the nature of the symptom sensations and provoking, exacerbating, or relieving factors. Carlsson R, Dent J, Bolling-Sternevald E et al. The usefulness of a structured questionnaire in the assessment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998; 33:1023–1029. To be able to score GERD-related symptoms in a quantitative way. Maximum score is 6 points. With such a score the reflux interferes constantly with daily activities, and there is occasional pulmonary aspiration. DeMeester TR, Johnson LF. The evaluation of objective measurements of gastroesophageal reflux and their contribution to patient management. Surg Clin North Am. 1976;56: 39–53. To develop a self-report questionnaire to measure gastroesophageal reflux disease in the general population. To measure symptoms experienced over the prior year and to collect the medical history. This is a valid questionnaire that is applicable in population-based studies to assess gastroesophageal reflux disease. Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:539–547. The aim was to design a scoring system to predict findings on the basis of clinical information. Points are assigned for specific characteristics, and then summed to give the total score. To obtain a predicted probability, a constant is subtracted from the total score and this difference multiplied by another constant (see formula). Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Can symptoms predict endoscopic findings in GERD? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58: 661–670. To develop a brief, reliable, and valid self-administered questionnaire that can facilitate the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Regurgitation Acid taste severity Movement of materials severity Acid taste frequency Movement of materials frequency Heartburn Frequency of burning behind breastbone Severity of burning behind breastbone Frequency of pain behind breastbone Severity of pain behind breastbone Dyspeptic symptoms Upper stomach pain severity Upper stomach pain frequency Upper stomach burning frequency Upper stomach burning severity Response options are scaled as closed-ended and Likert-type, with categories ranging from 1 to 5 or with 1–7 points for frequency, severity, and duration of symptoms. From Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ et al. Initial validation of a diagnostic questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:52–57. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. Content and wording of the RDQ are developed with multiple iterations of expert opinion and patient interviewing. The RDQ is a reliable and valid 12-item questionnaire of three scales (regurgitation, heartburn, dyspeptic symptoms). Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ et al. Initial validation of a diagnostic questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:52–57. Shaw MJ, Fendrick AM, Kane RL, Adlis SA, Talley NJ. Self-reported effectiveness and physician consultation rate in users of over-the-counter histamine-2 receptor antagonists. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:673–676. The GSAS is a very comprehensive evaluative symptom scale. It is a well-validated 15-item scale that includes associated symptoms as well as predominant symptoms. It also assesses different symptom dimensions (frequency of episodes, intensity of symptoms, level of distress). Subjects are first asked if they experienced the symptom (yes/no) during the past week. Asking the subject to indicate, “How many times in the past week did you have this symptom,” assesses frequency. The severity of each symptom is assessed on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (slight) to 4 (very severe). Distress is also assessed on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). The GSAS is self-assessed twice, once before and once after treatment. The scale does not assess nocturnal symptoms. Rothman M, Farup C, Stewart W, Helbers L, Zeldis J. Symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1540–1549. Damiano A, Handley K, Adler E, Siddique R, Bhattacharyja A. Measuring symptom distress and health-related quality of life in clinical trials of gastroesophageal reflux disease treatment: further validation of the Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Symptom Assessment Scale (GSAS). Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1530–1537. This symptom questionnaire is specifically designed for GERD. The GERD score consists of six questions on specific symptoms, but no questions on atypical symptoms. Both intensity and frequency of symptoms is monitored. The scale is applied before and 6 months after therapy. Allen CJ, Parameswaran K, Belda J, Anvari M. Reproducibility, validity, and responsiveness of a disease-specific symptom questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:265–270. This questionnaire comprises 10 items covering four dimensions (abdominal pain, reflux discomfort (acid regurgitation, heartburn), intestinal discomfort, and sleep dysfunction. The self-assessment scale is to be applied at study start and after 4 weeks of therapy. Dimenas E, Glise H, Hallerback B, Hernqvist H, Svedlund J, Wiklund I. Quality of life in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. An improved evaluation of treatment regimens? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:681–687. To develop a reflux disease activity index that can be used frequently and is inexpensive as compared to frequent endoscopy and pH monitoring. The index is to be administered at baseline and every 3 months thereafter. Spechler SJ, Williford WO, Krol WF et al. Development and validation of a gastroesophageal reflux disease activity index (GRACI). Gastroenterology 1990;98:130. Williford WO, Krol WF, Spechler SJ, and the VA Cooperative Study Group on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Development for and results of the use of a gastroesophageal reflux disease activity index as an outcome variable in a clinical trial. Control Clinical Trials. 1994;15:335–348. The ReQuest (Reflux Questionnaire) comprises 7 dimensions (general well-being, acid complaints, upper abdominal/stomach complaints, lower abdominal/digestive complaints, nausea, sleep disturbances, other complaints) tested by a leading question for frequency (7-point Likert scale) and intensity (100 mm visual analogue scale), making up the short version of ReQuest. The long version also includes 67 symptom descriptions that are assigned to the 7 dimensions. The dimensions are grouped into two subscales: (1) ReQuest-GI, including dimensions with GI complaints (acid complaints, upper abdominal/stomach complaints, and nausea); and (2) ReQuest-WSO, including dimensions affecting the aspects of well-being (general well-being, sleep disturbances, and other complaints). In a further development, the ReQuest symptom score is combined with the LA grading system of esophageal injury. Bardhan KD, Stanghellini V, Armstrong D, Berghofer P, Gatz G, Monnikes H. Evaluation of GERD symptoms during therapy. Part I. Development of the new GERD questionnaire ReQuest. Digestion. 2004;69:229–237. Monnikes H, Bardhan KD, Stanghellini V, Berghofer P, Bethke TD, Armstrong D. Evaluation of GERD symptoms during therapy. Part II. Psychometric evaluation and validation of the new questionnaire ReQuest in erosive GERD. Digestion. 2004;69:238–244. Bardhan KD, Armstrong D, Fass R, Berghöfer P, Gatz G, Mönnikes H. The ReQuest/LA classification: a novel, integrated approach for the comprehensive assessment of treatment outcome of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Abstract at 2005 World Congress of Gastroenterology. Numerous symptom scales have been used in the literature to measure GERD symptom severity, but most do not fulfill the essential requirements for validity. The reader is referred to the overview presented by Stanghellini et al. and Rentz et al. (see table opposite). Rentz AM, Battista C, Trudeau E. Symptom and health-related quality-of-life measures for use in selected gastrointestinal disease studies: a review and synthesis of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:349–363. Stanghellini V, Armstrong D, Monnikes H, Bardhan KD. Systematic review: do we need a new gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004; 19:463–479. (1) Greatorex R, Thorpe JA. Clinical assessment of gastroesophageal reflux by questionnaire. Br J Clin Pract. 1983;37(4):133–5. (2) Reidel WL, Clouse RE. Variations in clinical presentation of patients with esophageal contraction abnormalities. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30(11):1065–71. (3) Andersen LI, Madsen PV, Dalgaard P, Jensen G. Validity of clinical symptoms in benign esophageal disease, assessed by questionnaire. Acta Med Scand. 1987;221(2):171–7. (4) Dimenäs E, Glise H, Hallerback B, Hernqvist H, Svedlund J, Wiklund I. Quality of life in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. An improved evaluation of treatment regimens? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:681–7. (5) Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS—a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988; 33:129–34. (6) Talley NJ, Fullerton S, Junghard O, Wiklund I. Quality of life in patients with endoscopy-negative heartburn: reliability and sensitivity of disease-specific instruments. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):1998–2004. (7) Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1998;7(1):75–83. (8) Mold JW, Reed LE, Davis AB, Allen ML, Decktor DL, Robinson M. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in elderly patients in a primary care setting. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;8:965–70. (9) Ruth M, Mansson I, Sandberg N. The prevalence of symptoms suggestive of esophageal disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26(1):73–81. (10) Räihä IJ, Impivaara O, Seppala M, Sourander LB. Prevalence and characteristics of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992; 40(12):1209–11. (11) Johnsson F, Roth Y, Damgaard Pedersen NE, Joelsson B. Cimetidine improves GERD symptoms in patients selected by a validated GERD questionnaire. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7(1):81–6. (12) Orenstein SR, Cohn JF, Shalaby TM, Kartan R. Reliability and validity of an infant gastroesophageal reflux questionnaire. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1993;32(8):472–84. (13) Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Cohn JF. Reflux symptoms in 100 normal infants: diagnostic validity of the infant gastroesophageal reflux questionnaire. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1996;35(12):607–14. (14) Locke GR, Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. A new questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69(6):539–47. (15) Williford WO, Krol WF, Spechler SJ. Development for and results of the use of a gastroesophageal reflux disease activity index as an outcome variable in a clinical trial. VA Cooperative Study Group on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Control Clin Trials. 1994;15(5):335–48. (16) Carlsson R, Dent J, Bolling-Sternevald E et al. The usefulness of a structured questionnaire in the assessment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33(10):1023–9. (18) Shaw MJ, Beebe TJ, Adlis A, Talley NJ. Reliability and validity of the digestive health status instrument in samples of community, primary care, and gastroenterology patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:981–7. (19) Ho KY, Kang JY, Seow A. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in a multiracial Asian population, with particular reference to reflux-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(10):1816–22. (20) Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J 3rd, Wiltgen C, Zinsmeister AR. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;11:671–4. (21) Manterola C, Munoz S, Grande L, Riedemann P. Construction and validation of a gastroesophageal reflux symptom scale. Preliminary report. Rev Med Chil. 1999; 127(10):1213–22. (22) Manterola C, Munos S, Grande L, Bustbos L. Initial validation of a questionnaire for detecting gastroesophageal reflux disease in epidemiological settings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:1041–5. (23) Allen CJ, Parameswaran K, Belda J, Anvari M. Reproducibility, validity, and responsiveness of a disease-specific symptom questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13(4):265–70. (24) Rothman M, Farup C, Stewart W, Helbers L, Zeldis J. Symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46(7):1540–9. (25) Shaw MJ, Talley NJ, Beebe TJ, et al. Initial validation of a diagnostic questionnaire for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):52–7. (26) Ofman JJ, Shaw M, Sadik K, et al. Identifying patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47: 1863–9. To score dysphagia of patients with malignant esophagogastric obstruction treated with the use of self-expanding metal stents. Grade Symptoms 0 Able to eat a normal diet 1 Able to eat some solid food 2 Able to eat some semi-solids only 3 Able to swallow liquids only 4 Complete dysphagia From Ogilvie AL, Dronfield MW, Ferguson R, Atkinson M. Palliative intubation of oesophagogastric neoplasms at fibreoptic endoscopy. Gut. 1982;23:1060–1067. With permission of BMJ Publishing Group. The dysphagia score improves after stent placement from a mean of 3.6 to 1.6 after two weeks. Ogilvie AL, Dronfield MW, Ferguson R, Atkinson M. Palliative intubation of oesophagogastric neoplasms at fibreoptic endoscopy. Gut. 1982;23:1060–1067. Siersema PD, Schrauwen SL, Blankenstein M van et al. Self-expanding metal stents for complicated and recurrent esophagogastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54: 579–586. To grade dysphagia in esophageal malignancies. The Sugahara dysphagia grading is divided into 6 categories, grade 1 is the least, and grade 6 the most severe: Grade 1 is defined as eating normally. Grade 2 patients require liquids with meals. Grade 3 dysphagia is when a patient is able to take semi-solids but unable to take any solid food. Grade 4 patients can take liquids only. Grade 5 patients are unable to take liquids, but still able to swallow saliva. Grade 6 patients are unable to swallow saliva. Scoring system used in palliative treatment of patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Sugahara S, Ohara K, Yoshioka H. Improvement of swallowing function in patients with esophageal cancer treated by radiology. J Jpn Soc Cancer Ther. 1996;31:1124–1130. To analyze the outcome of patients with strictures of the esophagus after radiotherapy for carcinoma. Score 1 Normal, eats anything 2 Eats soft food only 3 Eats pureed foods only 4 Drinks liquid only 5 No swallowing at all Score I Mean swallowing score 1 and 2; dilatation required at intervals longer than 6 months II Mean swallowing score 1 and 2; dilatation required at intervals between 3–6 months III Mean swallowing score 3 or requires dilatation every 1–3 months IV Mean swallowing score 4 or less, or requires dilatation monthly Reproduced from O’Rourke IC, Tiver K, Bull C, Gebski V, Langlands AO. Swallowing performance after radiation therapy for carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 1988;61:2022–2026. With permission granted by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. on behalf of the BJSS, Ltd. Patients are treated with dilatation. Score III is the most common success score. O’Rourke IC, Tiver K, Bull C, Gebski V, Langlands AO. Swallowing performance after radiation therapy for carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 1988;61:2022–2026. To score success rates in long-term follow-up after pneumodilatation for achalasia. Class Description 1. Excellent Completely free of symptoms 2. Good Occasional (< once a week) dysphagia or pain of short duration; defined as retrosternal hesitancy of food lasting from a few seconds (2–3 sec) to a couple of minutes (2–3 min) and disappearing after drinking fluids 3. Moderate Dysphagia > once/week, lasting < a few minutes and not accompanied by regurgitations or weight loss 4. Poor Dysphagia > once/week or lasting a few minutes or accompanied by regurgitations or weight loss From Vantrappen G, Hellemans J. Treatment of achalasia and related motor disorders. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:144–154. With permission from the American Gastroenterological Association. Excellent and good results are considered treatment success. Patients can have subjective improvement of symptoms but still score a “poor” result because of continuing dysphagia, weight loss, or regurgitation. Vantrappen G, Hellemans J. Treatment of achalasia and related motor disorders. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:144–154. To evaluate the severity of achalasia symptoms in a trial that compared botulinum toxin to pneumatic dilatation. Symptom Score Dysphagia 1 = once per month or less 2 = once per week, up to 3 to 4 times a month 3 = two to four times per week 4 = once per day 5 = several times per day Regurgitation 1 = once per month or less 2 = once per week, up to 3 to 4 times a month 3 = two to four times per week 4 = once per day 5 = several times per day Chest pain 1 = once per month or less 2 = once per week, up to 3 to 4 times a month 3 = two to four times per week 4 = once per day 5 = several times per day Total symptom score From Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Wilcox CM et al. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomized trial. Gut. 1999;44:231–239. With permission of BMJ Publishing Group. The maximum score is 15. Clinical response is defined as a greater than 50 % improvement in the total symptom score. Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Wilcox CM et al. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomized trial. Gut. 1999;44:231–239. A careful interview and the use of modern methods that concentrate on pathophysiologic aspects always allow an early diagnosis and the initiation of therapy of achalasia. The final score is the sum of the individual ratings for each symptom/sign. Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732–38. Eckardt VF. Clinical presentation and complications of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:281–292. To describe the anatomic characteristics of each anomaly. Type A Common type: the most common anomaly, the esophagus ends in a blind pouch and the lower esophagus joins the respiratory tract near the tracheal bifurcation. B Common type with an atretic fistula: as type A, with in addition no lumen of the lower esophageal portion near the trachea. C Atresia without tracheo-esophageal fistula: second most common anomaly. There is a (wide) gap between the esophageal ends. D Atresia with tracheo-esophageal fistula to the upper esophagus. E Atresia with fistula to upper and lower pouches. F Tracheo-esophageal fistula without atresia. G As type F, with a diaphragm partly obstructing the esophageal lumen (or atretic esophagus with esophagus with fused fistulas from each end). Group A Birth weight > 2500 g and well Group B 1. Birth weight 1800 to 2500 g and well; or 2. Birth weight > 2500 g but moderate pneumonia and other congenital anomaly Group C 1. Birth weight < 1800 g; or 2. Birth weight > 1800 g with severe anomaly or pneumonia From Waterston DJ, Bonham Carter RE, Aberdeen E. Oesophageal atresia: Tracheo-oesophageal fistula. A study of survival in 218 infants. The Lancet. 1962;1:819–822. With permission of Elsevier. Type A and C are the most common types. Waterston established prognostic criteria in 1962 to distinguish between cases that could be treated during a single operative session. The criteria are no longer valid. Waterston DJ, Bonham Carter RE, Aberdeen E. Oesophageal atresia: Tracheo-oesophageal fistula. A study of survival in 218 infants. Lancet. 1962;1:819–822. Fig. 2.2 Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula: classification according to Waterston. To stage common esophagotracheal malformations. Type A Esophageal atresia without tracheoesophageal fistula B Atresia with proximal tracheoesophageal fistula C Atresia with distal tracheoesophageal fistula D Atresia with both proximal and distal fistula E Tracheoesophageal fistula without esophageal atresia F Esophageal stenosis Fig. 2.3 Esophageal malformation: classification according to Gross. Commonly used classification system of esophageal atresia and tracheo-esophageal fistula. Type C is most common. Gross RE. The Surgery of Infancy and Childhood. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1953. The aim was to classify small caliber esophagus into three groups. Type 1 Early small-caliber esophagus (eosinophilic esophagitis with dysphagia for solids but normal barium esophagogram and esophagoscopy) Type 2 Advanced small-caliber esophagus (eosinophilic esophagitis with dysphagia for solids and a small-caliber esophagus detectable on barium esophagogram and/or esophagoscopy) Type 3 Ringed esophagus (eosinophilic esophagitis with dysphagia for solids and a small caliber esophagus with rings or corrugated esophagus detectable on barium esophagogram and/or esophagoscopy) Vasilopoulos S, Shaker R. Defiant dysphagia: small-caliber esophagus and refractory benign esophageal strictures. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2001;3:225–230. With permission of Current Science, Inc. The small caliber esophagus has a smooth, diffusely narrow esophageal lumen that can be appreciated by barium esophagography or esophagoscopy. There is no stricture or cicatrization. This is a rare esophageal disease entity of which the long-term outcome is poorly known. Type 3 especially is clinically relevant. Vasilopoulos S, Shaker R. Defiant dysphagia: small-caliber esophagus and refractory benign esophageal strictures. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2001;3:225–230. Fig. 2.4 Ringed esophagus, with multiple concentric rings and normal overlying mucosa (Type 3). The aim is to be able to grade esophageal varices by endoscopic evaluation. Grading 1. Diameter of 2 mm or less, which are brought out only by compressing the esophageal wall with the tip of the instrument 2. Similar diameter, no compression needed 3. 3–4 mm 4. 5 mm or more 5. Small on top of the larger submucosal varices (bright red and telangiectatic cherry-red spots) From Dagradi AE, Rodiles DH, Cooper E, Stempien SJ. Endoscopic diagnosis of esophageal varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 1971;56:371–377. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. Grades 4 and 5 are potential bleeders. Dagradi AE, Rodiles DH, Cooper E, Stempien SJ. Endoscopic diagnosis of esophageal varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 1971; 56:371–377. Dagradi AE, Ruiz RA, Weingarten ZG. Influence of emergency endoscopy on the management and outcome of patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Analysis of 500 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72:403–415. To grade esophageal varices by endoscopic evaluation. Grade I Smaller than 2 mm, visible only on deep inspiration II Diameter 2–3 mm (clearly visible varices) III Diameter 3–4 mm (prominent, locally coil-shaped varices, partially occupying the lumen) IV Diameter 4–5 mm (tortuous, sometimes grape-like varices) V Diameter larger than 5 mm, often with superimposed cherry red spots or red wale markings From Tytgat GN, Mulder CJ, eds. Procedures in Hepatogastroenterology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. Grades IV and V are particularly prone to bleeding. Tytgat GN, Mulder CJ, eds. Procedures in Hepatogastroenterology. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. Fig. 2.5a–e Esophageal varices: grading according to Tytgat. a Grade I; b Grade II; c Grade III. Fig. 2.5d, e d Grade IV; e Grade V. To grade esophageal varices by their size in endoscopic evaluation. Grade I Flat varices, disappearing when insufflating air within the esophagus II Varices permanently visible in the lumen of the esophagus but appearing in well-separated bands III Varices that are extremely prominent in the lumen, so that they appear to almost occlude the lumen of the esophagus when not inflated To estimate the varices diameter with the width of an open biopsy forceps. Grade 0 Nil I One-fourth bite width II One-half bite width III Three-fourth bite width IV One or more bite widths The height of the esophageal varices is compared with the width of biopsy forceps with a bite width of 5 mm. Conn HO, Binder H, Brodoff M. Fiberoptic and conventional esophagoscopy in the diagnosis of esophageal varices. A comparison of techniques and observers. Gastroenterology. 1967;52:810–818. Conn HO, Brodoff M. Emergency esophagoscopy in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage; a critical evaluation of its diagnostic accuracy. Gastroenterology. 1964; 47:505–512. Proposing standards for recording endoscopic findings of esophageal varices. Total score Rate of bleeding (%) >+ 1.14 0 + 0.38~ + 1.14 20.6 0~ + 0.38 40.0 –0.38~ 0 64.5 –1.14~ –0.38 90.2 <–1.14 100 From Beppu K, Inokuchi K, Koyanagi N et al. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endoscopy. 1981;27:213–218. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The rules for recording endoscopic findings in esophageal varices were proposed by the Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension. The total score is calculated as follows: S = XF + XC + XRWM + XCRS +XHCS + XE According to Beppu, the following signs are particularly valuable for predicting rebleeding: blue varices, red wale marking, cherry-red spots, and large-sized varices. Beppu K, Inokuchi K, Koyanagi N et al. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endoscopy. 1981;27:213–218. Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension. The general rules for recording endoscopic findings on esophageal varices. Jpn J Surg. 1980;10:84–87. Japanese Research Committee on Portal Hypertension. The general rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophageal varices, revised edition. Acta Hepatol Jpn. 1991;33: 277–281. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophageal varices were made in 1980. In 1991 the rules were revised as new modalities of endoscopic treatment were developed. Category Code Subcategory Location L Longitudinal extent Locus superior (ls) Locus medialis (Lm) Locus inferior (Li) Locus gastrica (Lg) Gastric varices adjacent to the cardiac orifice (Lg-c) Form F Shape and size Lesions assuming varicose appearance (F0) Straight small-caliber varices (F1) Moderately enlarged, beady varices (F2) Markedly enlarged, nodular, or tumor-shaped varices (F3) Color C Fundamental color White varices (Cw) Blue varices (Cb) Red color sign RC Red wale marking (RWM) Cherry red spot (CRS) Hematocystic spot (HCS) RC (–) RC (+) RC (++) RC (+++) Telangiectasia [TE(+)] Bleeding sign B During bleeding Spurting Oozing After hemostasis Red plug White plug Mucosal findings E Erosion (E) Ul Ulcer (U) S Scar (S) From Idezuki Y. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (1991). Japanese Society for Portal Hypertension. World J Surg. 1995;19:420–422. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. This scoring system is used for endoscopic evaluation of the therapeutic effect of sclerotherapy for esophageal varices. Idezuki Y. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (1991). Japanese Society for Portal Hypertension. World J Surg. 1995;19:420–422. To identify prospectively patients with the highest risk of bleeding. Fig. 2.6 Endoscopic views showing grading of varices by size (F1, F2, F3). Fig. 2.7a–c Endoscopic views showing various red color signs. a Cherry-red spots (arrows). b Wale markings (arrow). c Hematocystic spot (arrow). NIEC Index Rate of bleeding (%) at 1 year 1 < 20.0 1.6 2 20.0–25.0 11.0 3 25.1–30.0 14.8 4 30.1–35.0 23.3 5 35.1–40.0 37.8 6 > 40.0 68.9 From Northern Italian Endoscopy Club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices: a prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:983–989. With permission of the New England Journal of Medicine. This score uses only three variables, one of which is the Child– Pugh classification, the other two are endoscopically scored features of the varices. The grading of the size of the varices is based on the scoring of the Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension. Northern Italian Endoscopy Club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices: a prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:983–989. Merkel et al. revised the NIEC index after performing a prospective study to predict the first esophageal variceal hemorrhage. The size and presence of red wale markings are more important than the Child–Pugh class for the prediction of esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Revised coefficient Regression NIEC Size of varices 1.12 0.4365 Red wale markings 0.36 0.3193 Child–Pugh class 0.04 0.645 From Merkel C, Zoli M, Siringo S et al. Prognostic indicators of risk for first variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a multicenter study in 711 patients to validate and improve the North Italian Endoscopic Club (NIEC) index. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2915–2920. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. This index resembles the Paquet and Sarin grading systems because of the weighting of the revised NIEC index, with a low coefficient for the Child–Pugh class. Merkel C, Zoli M, Siringo S et al. Prognostic indicators of risk for first variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a multicenter study in 711 patients to validate and improve the North Italian Endoscopic Club (NIEC) index. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95: 2915–2920. To select high-risk patients for prophylactic sclerotherapy. Existence of varices III–IV bearing erosions Varices II–IV without erosions but coagulation factors below 30% Or both Fig. 2.8 Endoscopic degree of esophageal varices according to Pacquet. The black points (degree IV) signal possible danger of bleeding. Paquet KJ. Prophylactic endoscopic sclerosing treatment of the esophageal wall in varices—a prospective controlled randomized trial. Endoscopy. 1982;14:4–5. The criteria are based on the size of the varices, erosions, and the presence of coagulopathy. Paquet KJ. Prophylactic endoscopic sclerosing treatment of the esophageal wall in varices—a prospective controlled randomized trial. Endoscopy. 1982;14:4–5. To grade varices for sclerotherapy according to the degree of protrusion into the lumen. Grade 1 Varix is flush with the wall of the esophagus Grade 2 Protrusion of varix no further than half-way down the center of the lumen Grade 3 Protrusion more than half-way down the center of the lumen Fig. 2.9 Esophageal Varices: Grading of variceal size according to Westaby. From Westaby D, MacDougall BRD, Melia W, Theodossi A, Williams R. A prospective randomized study of two sclerotherapy techniques for esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1983;3:681–684. With permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Westaby D, MacDougall BRD, Saunders JB et al. A study of risk factors in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. In: Westaby D, MacDougall BRD, Williams R, eds. Variceal Bleeding. London: Pittman Medical; 1982. Westaby D, MacDougall BRD, Melia W, Theodossi A, Williams R. A prospective randomized study of two sclerotherapy techniques for esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1983;3: 681–684. To identify cirrhotic patients that have never had variceal hemorrhage and who are most prone to bleeding. Endoscopic sign Assigned rating Form or size F1 Small and straight varices, not disappearing with insufflation 1 F2 Large tortuous varices, occupying less than one-third of lumen 2 F3 Largest size varices, coil shaped, occupying more than one-third of the lumen 3 Location Li Within the lower one-third 1 Lm Within the lower two-thirds, below tracheal bifurcation 2 Ls Extending above the tracheal bifurcation to the cricopharyngeus 3 Color Cw White varices appearing like large folds of esophageal mucosa 1 Cbw Varices that cannot be clearly assigned to Cb or Cw 2 Cb Dark blue varices, appearing cyanotic 3 Red color sign + Present but no more than 10 lesions found 1 ++ Not extensive, but more than 10 lesions are easily visible 2 +++ Extensive, covering all varices in the entire esophagus 3 From Snady H, Feinman L. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:519–525. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. A score ≥ 8 is classified as high grade. A score ≤ 7 is classified as low grade. In a prospective trial with a mean duration of 26 months, the association with bleeding for high grade was 73 % versus 7 % for low grade. Snady H, Feinman L. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:519–525. To determine the indication of endoscopic variceal ligation based on the vascular pattern classified by three-dimensional endoscopic ultrasonography. Type Description 1 Cardial inflow without para-esophageal veins 2 Cardial inflow with para-esophageal veins 3 Azygous-perforating pattern 4 Complicated pattern Fig. 2.10a–d Esophageal varices: classification of vascular patterns based on 3-D endoscopic ultrasonographic findings. a Type 1: cardial-inflow type without paraesophageal veins; b Type 2: cardial-inflow type with paraesophageal veins; c Type 3: azygos-perforating pattern; d Type 4: complex pattern. From Nakamura S, Murata Y, Mitsunaga A et al. Evaluation of endoscopic treatment for esophageal varices by three-dimensional endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:140. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. From Nakamura S, Murata Y, Mitsunaga A, Oi I, Hayashi N, Suzuki S. Hemodynamics of esophageal varices on three-dimensional endoscopic ultrasonography and indication of endoscopic variceal ligation. Digestive Endoscopy. 2000;15:289–297. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. Variceal ligation is particularly indicated for patients who have collaterals such as para-esophageal veins running parallel to the varices. Nakamura S, Murata Y, Mitsunaga A et al. Evaluation of endoscopic treatment for esophageal varices by three-dimensional endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:140. Nakamura S, Murata Y, Mitsunaga A, Oi I, Hayashi N, Suzuki S. Hemodynamics of esophageal varices on three-dimensional endoscopic ultrasonography and indication of endoscopic variceal ligation. Digestive Endoscopy. 2000;15:289–297. To determine the spectrum of Candida esophagitis. Grade Appearance I A few raised whitish plaques up to 2 mm in diameter, with hyperemia but no edema or ulceration II Multiple raised white plaques larger than 2 mm in size, with hyperemia, edema but no ulceration III Confluent linear and nodular elevated plaques, with hyperemia and frank ulceration IV The findings for grade III plus increased friability of the mucous membrane and occasional narrowing of the lumen Fig. 2.11a, b Esophageal candidiasis: endoscopic grading system. a Kodsi Grade II; b Kodsi Grade IV. From Kodsi BE, Wickremesinghe C, Kozinn PJ, Iswara K, Goldberg PK. Candida esophagitis: a prospective study of 27 cases. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:715–719. With permission from the American Gastroenterological Association. This grading system is used for controlled studies for the treatment of Candida esophagitis. Kodsi BE, Wickremesinghe C, Kozinn PJ, Iswara K, Goldberg PK. Candida esophagitis: a prospective study of 27 cases. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:715–719. To score symptoms related to Candida esophagitis. Grade 0 Absence of symptoms Grade I Symptoms of mild entity not compromising the capability to swallow both solid and liquid substances Grade II Symptoms of moderate entity not compromising (grade IIa) or compromising (grade IIb) the capability to swallow solid substances, but not compromising the capability to swallow liquid substances Grade III Symptoms of severe entity, compromising either the capability to swallow solid substances only (grade IIIa) or compromising the capability to swallow both solid and liquid substances (grade IIIb) From Barbaro G, Barbarini G, Di Lorenzo G. Fluconazole vs. itraconazole-flucytosine association in the treatment of esophageal candidiasis in AIDS patients, a double blind, multicenter placebo-controlled study. Chest. 1996;110:1507–1514. With permission from The American College of Chest Physicians. This score is used for randomized studies for the treatment of Candida esophagitis. Barbaro G, Barbarini G, Di Lorenzo G. Fluconazole vs. itraconazole-flucytosine association in the treatment of esophageal candidiasis in AIDS patients, a double blind, multicenter placebo-controlled study. Chest. 1996;110: 1507–1514. To produce an objective measure of esophageal acid exposure based on 24-hour pH scoring. 24-hour pH monitoring components Normal value Supine period < 1.2 % (0.286 ± 0.467) Total period < 4.2 % (1.47 ± 1.38) # Episodes > 5 min 3 or less (0.64 ± 1.28) Longest episode < 9.2 min (3.83 ± 2.78) Upright period < 6.3 % (2.33 ± 1.97) # Total episodes < 50 (18.93 ± 13.78) From Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Twenty-four hour pH monitoring of the distal esophagus. A quantitative measure of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1974;62:325–332. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. A 24-hour pH score is determined by calculating the number of standard deviation equivalents in each measured value of the six components. One starts at a fixed reference point placed two standard deviations below the respective measured mean value in controls. This is a commonly used scoring system for acid reflux. DeMeester TR, Johnson LF. The evaluation of objective measurements of gastroesophageal reflux and their contribution to patient management. Surg Clin North Am. 1976;56:39–53. DeMeester TR, Wang CI, Wernly JA et al. Technique, indications, and clinical use of 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1980;79:656–670. Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Twenty-four hour pH monitoring of the distal esophagus. A quantitative measure of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1974;62:325–332. Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Development of the 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring composite scoring system. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8(Suppl 1):52–58. To classify reflux esophagitis into different grades by endoscopic evaluation. Grade I One or more nonconfluent erythematous spots or superficial erosions II Confluent erosive or exudative mucosal lesions which do not extend around the entire esophageal circumference III Erosive or exudative mucosal lesions which cover the whole esophageal circumference and lead to inflammation of the wall without stricture IV Chronic mucosal lesions, interpreted as esophageal ulcer, mural fibrosis, stricture, shortening, and scarring with columnar (Barrett’s) epithelium Grade I Erythematous or erythemato-exudative erosion (alone or multiple) which can cover several folds (as long as they are not confluent) II Confluent but not circumferential III Circumferential erosive and exudative lesions IV (a) Chronic lesions (ulcer, stenosis, endobrachyesophagus, cylindric cell epithelialization) with active inflammation (b) Cicatricial stage (stenosis, brachyesophagus, cylindric cell epithelialization) without active inflammation Grade I Isolated (or sometimes multiple) erythematous or erythemato-exudative erosion, covering a single mucosal fold II Multiple erosions covering several mucosal folds partly confluent but never circumferential III Circular extension of erosive and exudative lesions IV (a) Ulcer (b) Fibrosis (leading to stenosis and brachyesophagus) V Presence of cylindric cell epithelialization acquired in the form of a disc, strip, or sleeve From Ollyo JB, Lang F, Fontolliet C, Monnier P. Savary–Miller’s new endoscopic grading of reflux-oesophagitis: a simple, reproducible, logical, complete and useful classification. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:100. With permission from the American Gastroenterological Association. In 1977 Miller included the Savary grading of esophagitis in an atlas on digestive tract fiberscopy. Since then the grading has been known as Savary–Miller. In 1981 stage 4 was divided into two subgroups: stage 4a: associated with erosive or ulcerated lesions; stage 4b: not associated with erosive ulcerated lesions. In 1989 Monnier improved the grading system by modifying stage 1 and 2 and by adding stage 5 to include cylindric cell scars. Miller G, Savary M, Monnier P. Notwendige Diagnostik: endoskopie. In: Blum AL, Siewert JR, eds. Reflux-therapie. Berlin: Springer; 1981:336–354. Ollyo JB, Monnier P, Fontolliet C, Savary M. Classification endoscopique de l’esophagite par reflux. Paris: Résumé du Video Digest; 1989:145–155. Ollyo JB, Lang F, Fontolliet C, Monnier P. Savary–Miller’s new endoscopic grading of reflux-oesophagitis: a simple, reproducible, logical, complete and useful classification. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:100. Ollyo JB, Fontolliet C. Nouvelle classification Lausannoise des oesophagites de reflux. Acta Endoscopica. 1991;21:383–388 Savary M. La séméiologie endoscopique de l’incontinence gastro-oesophagienne [thesis]. Départment ORL, Université de Lausanne, Suisse, 1967. Savary M, Miller G. L’oesophage. Manuel et atlas d’endoscopie. Soleure, Switzerland: Editions Gassmann S.A; 1977. Savary M, Miller G. The esophagus: Handbook and Atlas of Endoscopy. Soleure, Switzerland: Editions Gassmann S.A; 1978:135–144. To define the severity of endoscopically detectable reflux-induced injury of the squamous esophageal lining. Grade 0 Normal mucosa (no abnormalities noted) Grade I Erythema, hyperemia, and/or friability present (no macroscopic erosions visible) Grade II Superficial ulceration or erosions involving < 10 % of the mucosal surface area on the distal 5 cm of esophageal squamous mucosa Grade III Superficial ulceration or erosions involving ≥ 10% but < 50% of the mucosal surface area on the distal 5 cm of esophageal squamous mucosa Grade IV Deep ulceration anywhere in the esophagus or confluent erosion of > 50% of the mucosal surface area on the last 5 cm of esophageal squamous mucosa Grade V Stricture that precludes the passage of the endoscope From Hetzel DJ, Dent J, Reed WD et al. Healing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:903–912. With permission from the American Gastroenterological Association. Estimation of the damaged surface area is difficult and prone to error. Grade I is based on the so-called minor or equivocal changes without tissue breaks which are poorly reproducible. The system is not validated for intra- and inter-observer variability. Hetzel DJ, Dent J, Reed WD et al. Healing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:903–912. The aim here was to produce a simple clinician-friendly grading system using unequivocal terminology. Grade Description A One or more mucosal breaks confined to the folds, each no longer than 5 mm B At least one mucosal break more than 5 mm long confined to the mucosal folds but not continuous between the tops of the mucosal folds C At least one mucosal break continuous between the tops of two or more mucosal folds, but not circumferential D Mucosal break ≥ three-quarters of circumference From Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL et al. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85–92. With permission from the American Gastroenterological Association. The Los Angeles system is the only classification which has been validated and which has been shown to be responsive to acid suppressant therapy. Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL et al. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85–92. Lundell L, Dent J, Bennet JR et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis—clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles Classification. Gut 1999;45: 172–80. Fig. 2.12a–d a Two single erosions, both < 5 cm. Savary–Miller grade II, Hetzel grade II, and Los Angeles grade A. b Multiple long linear erosions, with a 3-cm hiatal hernia. Savary–Miller grade II, Hetzel grade II, and Los Angeles grade B. c Erosions with whitish exudates involving the longitudinal folds and extending into the valley between folds. A stricture is also present. Savary–Miller grade IV, Hetzel grade III, and Los Angeles grade C. d Example of deep circumferential esophageal ulcers, with stenosis of the lumen. Los Angeles grade D. To describe the appearance of the Z-line or squamocolumnar mucosal junction. Grade Z-line appearance Comments 0 Sharp and circular Z-line may be wave-like because of the mucosal folds; no narrow linear extensions (tongues) or islands of columnar epithelium I Irregular with tongue-like protrusions and/or islands of columnar-appearing epithelium II A distinct, obvious tongue of columnar-appearing epithelium < 3 cm in length Width of tongue at the base must be less than its length III Distinct tongues of columnar-appearing epithelium > 3cm in length or Cephalad displacement of Z-line > 3cm From Wallner B, Sylvan A, Stenling R, Janunger KG. The esophageal Z-line appearance correlates to the prevalence of intestinal meta-plasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:17–22. By permission of Taylor & Francis AS. The classification is based on a threshold of 3 cm when describing the extent of intestinal metaplasia. Tewari V, Tewari D, Solanki K et al. Assessment of squamocolumnar junction in distal esophagus using ZAP classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:136. Wallner B, Sylvan A, Stenling R, Janunger KG. The esophageal Z-line appearance correlates to the prevalence of intestinal metaplasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:17–22. Wallner B, Sylvan A, Janunger KG. Endoscopic assessment of the “Z-line” (squamocolumnar junction) appearance: reproducibility of the ZAP classification among endoscopists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:65–69. To produce a comprehensive grading system including anatomical functional and pathologic features. A = anatomy 0 No hiatal hernia on routine radiology (no provocative maneuvers) or endoscopy 1 Sliding hiatal hernia which reduces on screening or spot film radiology 2 Sliding hiatal hernia which was not seen to reduce on screening or spot films 3 Mixed sliding and paraesophageal hernia or pure paraesophageal hernia F = function (pH assessment) 0 No pathologic reflux on 24-hour pH testing 1 Reflux related to meals 2 Upright reflux not related to meals 3 Supine reflux with or without upright reflux* P = pathology** 0 No macroscopic mucosal abnormality 1 Macroscopic esophagitis consisting of at least linear streaks in the distal esophagus 2 Concentric fibrosis (= stricture) 3 Longitudinal fibrosis (= short esophagus) or penetrating ulcer The AFP score is easy to use in clinical practice. It enables a detailed description of the preoperative and postoperative condition of the patient undergoing anti-reflux surgery. Full coding might read as follows: A2, F3, N, P1, CLO, PS. Little AG, Ferguson MK, Skinner DB. Diseases of the Esophagus. Vol II: Benign Diseases. Mount Kisco, NY: Futura Publishing Company Inc; 1990:177–180. To grade the presence and significance of a gastroesophageal flap valve at the gastroesophageal junction by retroflexed endoscopy. Grade 1 Prominent fold of tissue along the lesser curvature, closely opposed to the endoscope Grade 2 Fold present, but periods of opening and rapid closing around the endoscope Grade 3 Fold is not prominent and the endoscope is not tightly gripped by the tissue Grade 4 No fold recognizable and the lumen of the esophagus gaped open, allowing the squamous epithelium to be viewed from below; hiatal hernia From Hill LD, Kozarek RA, Kraemer SJ et al. The gastroesophageal flap valve: in vitro and in vivo observations. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44: 541–547. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Grades 1 and 2 are graded as “normal” appearance, and grades III and IV as “reflux” appearance. Hill LD, Kozarek RA, Kraemer SJ et al. The gastroesophageal flap valve: in vitro and in vivo observations. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:541–547. Fig. 2.13a–d Gastroesophageal reflux: grading the gastroesophageal flap valve. a Grade 1; b Grade 2; c Grade 3; d Grade 4. To produce an accurate and reproducible assessment of the endoscopic extent of esophageal columnar metaplasia, applicable in clinical practice. The length of esophagus lined circumferentially (C) with columnar mucosa is measured in addition to the total length (M) of esophagus involved with columnar mucosa at any point Fig. 2.14 Columnar metaplasia: the Prague Barrett’s C and M endoscopic criteria. From Armstrong D. Review article: towards consistency in the endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus and columnar metaplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(5):40–47. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. The International Working Group on the Classification of Esophagitis developed the CM classification. A clear definition of endoscopic landmarks for the identification and localization of the gastroesophageal junction as well as the squamocolumnar junction is essential. Armstrong D. Review article: towards consistency in the endoscopic diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus and columnar metaplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(5):40–47. This classification system was established to train endoscopists to detect mucosal changes and to define a reproducible terminology. Pattern I Round pits: characterized by an organized and regularly arranged area of circular dots Pattern II Reticular: characterized by circular or oval similarly shaped tubules in regular arrangement Pattern III Villous: characterized by a fine villiform appearance with a regular shape and arrangement without any pits Pattern IV Ridged: characterized by a cerebriform appearance consisting of a thick villous convoluted shape with a regular arrangement From Guelrud M, Herrera I, Essenfeld H, Castro J. Enhanced magnification endoscopy: a new technique to identify specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53: 559–565. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Round pits pattern Formerly Pattern I, small round pits with a uniform dot-like appearance, signifying fundic columnar epithelium Tubular pits pattern Formerly Pattern II, ovoid or short tubular pits with a uniform arrangement, signifying cardia mucosal Thin linear pattern New category, thin superficial grooves that may represent cardia mucosa and/or Barrett’s epithelium Deep linear pattern New category, deep, coarse grooves signifying Barrett’s epithelium Villous pattern Formerly Pattern III, uniform mesh-like villous appearance or, more rarely, fingerlike projections, signifying Barrett’s epithelium Foveolar pattern New category, flat surface interspersed with wide circular pits and the absence of villous structures, signifying Barrett’s epithelium Cerebroid pattern Formerly Pattern IV, uniform thick, straight tubular or convoluted ridges reminiscent of cerebral gyri, signifying Barrett’s epithelium From Guelrud M, Ehrlich EE. Endoscopic classification of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:58–65. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. In 2004 the original patterns were renamed, and three new categories were added: thin linear, deep linear, and foveolar. In the new classification, detailed mucosal surface descriptions were substituted for mucosal “patterns.” Guelrud M, Herrera I, Essenfeld H, Castro J. Enhanced magnification endoscopy: a new technique to identify specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:559–565. Guelrud M, Ehrlich EE. Endoscopic classification of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:58–65. To classify pit patterns of Barrett’s esophagus by magnifying endoscopy. Pit-1 Small round Small round pits of relatively uniform size and shape Pit-2 Straight Long straight lines Pit-3 Long oval Exhibits long extended pits, larger than those of the dot type Pit-4 Tubular Complicated and twisted pattern that is similar to a branch or gyrus like structure Pit-5 Villous Flat, finger-like projections Fig. 2.15 Columnar metaplasia: Classification of Barrett’s epithelium by magnifying endoscopy according to Endo. From Endo T, Awakawa T, Takahashi H et al. Classification of Barrett’s epithelium by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55: 641–647. With permission from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The classification of the superficial mucosal appearance of Barrett’s epithelium by magnifying endoscopy reflects histologic features and mucin phenotypes. Endo T, Awakawa T, Takahashi H et al. Classification of Barrett’s epithelium by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:641–647. To determine the sensitivity and specificity of magnification endoscopy for the detection of intestinal metaplasia by using a revised pit classification. Three types of mucosal pattern are classified: Type 1 Normal pits Type 2 Slit-reticular pattern Type 3 Gyrus-villous pattern See Fig. 2.16 next page. From Toyoda H, Rubio C, Befrits R, Hamamoto N, Adachi Y, Jaramillo E. Detection of intestinal metaplasia in distal esophagus and esophagogastric junction by enhanced-magnification endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:15–21. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The presence of type 1 and type 2 surface patterns are characteristic of, respectively, fundic epithelium and cardiac epithelium. The type 3 pattern correlated with intestinal metaplasia. Toyoda H, Rubio C, Befrits R, Hamamoto N, Adachi Y, Jaramillo E. Detection of intestinal metaplasia in distal esophagus and esophagogastric junction by enhanced-magnification endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:15–21. Fig. 2.16a–e Classification of surface pattern of Barrett’s epithelium and esophagogastric junctional mucosa by enhanced magnifying endoscopy. a Small round pits of uniform size and shape (type 1, corpus). b Slit (arrows) and reticular (arrowhead) pattern (type 2, cardiac). c Gyrus pattern (type 3, intestinal metaplasia). d Villous pattern (type 3, intestinal metaplasia. e Mixed gyrus and villous pattern (type 3, intestinal metaplasia). Findings illustrated in c, d, and e constitutes a single mucosal pattern (type 3). To describe intra-papillary capillary loop patterns and the characteristic changes of carcinoma in situ. Typing IPCL and iodine staining pattern Type I (normal) Normal IPCL; iodine stained Type II (esophagitis) Dilatation and elongation of IPCL; slightly stained Type III (mild dysplasia) Minimal changes on IPCL; unstained Type IV (severe dysplasia) Two or three out of four changes; unstained Type V (carcinoma) All four changes on IPCL; unstained Infiltration Grade of IPCL destruction Description m1 Characteristic IPCL changes to intraepithelial carcinoma (Type V changes) only affect the top of the IPCL m2 Type V changes affect the middle part of the IPCL, and are observed as an elongation of the affected IPCL m3 Severely destroyed Type V changes affect the total length of the IPCL and the original shape of the IPCL has been destroyed sm Disappeared Abnormal tumor vessels with large diameters have appeared Fig. 2.17 Classification of IPCL according to Inoue. From Inoue H. Magnification endoscopy in the esophagus and stomach. Dig Endosc. 2001;13:40–41. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. The four characteristic changes in IPCL pattern are: dilatation, tortuous running, caliber changes, and shape. Inoue H. Magnification endoscopy in the esophagus and stomach. Dig Endosc. 2001;13:40–41. Inoue H, Honda T, Yoshida T et al. Ultra-high magnification endoscopy of the normal esophageal mucosa. Dig Endosc. 1996;8:134–138. Inoue H, Honda T, Nagai K et al. Ultra-high magnification endoscopic observation of carcinoma in situ of the esophagus. Dig Endosc. 1997;9:16–18. Inoue H, Youichi K, Yoshida T, Kawano T, Endo M, Iwai T. High-magnification endoscopic diagnosis of the superficial esophageal cancer. Dig Endosc. 2000;12:32–35. To describe a new endoscopic classification of esophageal cancer that includes both early and advanced lesions. Type 0 Superficial type Type 0–I Superficial and protruding type Type 0–II Superficial and flat type Type 0–IIa Slightly elevated type Type 0–IIb Flat type Type 0–IIc Slightly depressed type Type 0–III Superficial and distinctly depressed type Type 1: Protruding type Type 2: Ulcerative and localized type Type 3: Ulcerative and infiltrating type Type 4: Diffusely infiltrating type Type 5: Unclassified type Commonly used endoscopic grading system for early and advanced cancer. Japanese Society for Esophageal Diseases. Guidelines for Clinical and Pathologic Studies on Carcinoma of the Esophagus. 8th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara; 1992:31–58. Kumagai Y, Makuuchi H, Mitomi T, Ohmori T. A new classification system for early carcinomas of the esophagus. Dig Endosc. 1993;5:139–50. To estimate the depth of infiltration. m1: Epithelial cancer m2: Mucosal cancer with invasion between m1 and m3 m3: Mucosal cancer almost and/or already invading the lamina muscularis mucosae sm1: Submucosal cancer with invasion to the first third of the submucosal layer sm2: Submucosal cancer with invasion to the middle third of the submucosal layer sm3: Massive invasion of the cancer to the submucosal layer Fig. 2.18 Classification of depth of invasion of superficial esophageal cancer: the Japanese Society of Esophageal Disease. Depth of invasion of squamous cell neoplasia in the esophagus. Mucosal carcinoma is divided into three groups: m1 or intraepithelial, m2 or micro-invasive (invasion through the basement membrane), m3 or intramucosal (invasion to the muscularis mucosae). The depth of invasion in the submucosa is divided into three sections of equivalent thickness: superficial (sm1), middle (sm2), and deep (sm3). Increasingly used staging; lesions beyond sm1 are not amendable to endoscopic resection because of increased risk of lymph node metastasis. Japanese Society for Esophageal Diseases. Guidelines for the clinical and pathologic studies on carcinoma of the esophagus. 8th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara; 1992:31–58. TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed T0 No evidence of primary tumor Tis Carcinoma in situ T1 Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa T2 Tumor invades muscularis propria T3 Tumor invades adventitia T4 Tumor invades adjacent structures NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed N0 No regional lymph node metastasis N1 Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, 3 cm or less in greatest dimension MX Distant metastasis cannot be assessed M0 No distant metastasis M1 Distant metastases M1a Metastasis in celiac lymph nodes M1b Other distant metastasis M1a Not applicable M1b Nonregional lymph nodes and/or other distant metastasis M1a Metastasis in cervical nodes M1b Other distant metastasis GX Grade cannot be assessed G1 Well differentiated G2 Moderately differentiated G3 Poorly differentiated G4 Undifferentiated RX Presence of residual tumor cannot be assessed R0 No residual tumor R1 Microscopic residual tumor R2 Macroscopic residual tumor From Greene, FL, Page, DL, Fleming ID et al. Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed (2002) published by Springer-New York, www.springeronline.com. The AJCC TNM staging system uses three basic descriptors that are then grouped into stage categories. The first component is “T,” which describes the extent of the primary tumor. The next component is “N,” which describes the absence or presence and extent of regional lymph node metastasis. The third component is “M,” which describes the absence or presence of distant metastasis. The final stage groupings (determined by the different permutations of “T,” “N,” and “M”) range from Stage 0 through Stage IV. Greene, FL, Page, DL, Fleming ID et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer, 2002. http://www.cancerstaging.org/. To assess the preoperative risk for postoperative death after operation for resectable esophageal cancer. From Bartels H, Stein HJ, Siewert JR. Preoperative risk analysis and postoperative mortality of oesophagectomy for resectable oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:840–844. With permission granted by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. on behalf of the BJSS, Ltd. The total score ranges from 11 (without risk) to 33 (highest risk). On the basis of the score patients can be divided in three risk groups; “low risk” 11–15 points, “moderate risk” 16–21 points, “high risk” 22–33 points. Bartels H, Stein HJ, Siewert JR. Preoperative risk analysis and postoperative mortality of oesophagectomy for resectable oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:840–844. The aim here was to classify bronchoscopy findings in the pre-operative staging of supracarinal esophageal cancer. Category Bronchoscopy findings I No abnormalities IIa Slight compression of the trachea or bronchus; normal mobility of the wall; and parallel and regular longitudinal folds of the pars membranacea IIb Impingement or deviation of the trachea or bronchus or widening of the carina, associated with reduction of the mobility during coughing and breathing III Frank mucosal invasion From Choi TK, Siu KF, Lam KH, Wong J. Bronchoscopy and carcinoma of the esophagus I. Findings of bronchoscopy in carcinoma of the esophagus. Am J Surg. 1984;147:757–759. With permission from Excerpta Medica Inc. Airway involvement as in category IIb is a predictor of irresectability. Baisi A, Bonavina L, Peracchia A. Bronchoscopic staging of squamous cell carcinoma of the upper thoracic esophagus. Arch Surg. 1999;134:140–143. Choi TK, Siu KF, Lam KH, Wong J. Bronchoscopy and carcinoma of the esophagus I. Findings of bronchoscopy in carcinoma of the esophagus. Am J Surg. 1984;147:757–759. Choi TK, Siu KF, Lam KH, Wong J. Bronchoscopy and carcinoma of the esophagus II. Carcinoma of the esophagus with tracheobronchial involvement. Am J Surg. 1984;147:760–762. To classify esophagogastric tumors based on the anatomic location of the tumor center. Type I Adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus, which usually arises from an area with specialized intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus (i. e., Barrett’s esophagus) and may infiltrate the esophagogastric junction from above Type II True carcinoma of the cardia arising immediately at the esophagogastric junction Type III Subcardial gastric carcinoma that infiltrates the esophagogastric junction and distal esophagus from below From Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Carcinoma of the cardia: carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction—classification, pathology and extent of re-section. Dis Esophagus. 1996;9:173–182. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. Fig. 2.19 Classification of esophagogastric tumors according to Siewert: Type I, esophageal; type II, cardiac; type III, subcardiac. (Fein M et al. Surgery. 1998;124:707–714. Reproduction approved.) This classification was approved at a consensus conference of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus in 1997. The authors treat type I tumors as esophageal cancer and type II and III tumors as gastric cancer. Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Carcinoma of the cardia: carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction—classification, pathology and extent of resection. Dis Esophagus. 1996;9:173–182. Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1457–1459. The aim was to develop a questionnaire for measuring the global and personal impact of dyspeptic symptoms. (A) Frequency of dyspeptic symptoms Score Over the past six months how frequently have you experienced dyspeptic symptoms? Never 0 On only 1 or 2 days 1 On approximately 1 day per month 2 On approximately 1 day per week 3 On approximately 50 % of days 4 On most days 5 (B) Effect on normal activities Does the dyspepsia interfere with normal activities such as eating, sleeping, or socializing? Never 0 Sometimes 1 Regularly 2 (C) Time off work How many days have you lost off work due to your dyspepsia in the past six months? None 0 1–7 days 1 More than 7 days 2 (D) Consultation with medical profession How often have you attended a doctor due to dyspepsia in the past 6 months? None 0 Once 1 Twice or more 2 (E) GP visits to patient’s home How often have you called your GP to visit you at home because of your dyspepsia in the past six months? None 0 Once 1 Twice or more 2 (F) Tests for dyspepsia How many tests have you had for your dyspepsia in the past 6 months? None 0 One 1 Two or more 2 (G) Treatment for dyspepsia (1) Over the last six months, how frequently have you used drugs that you have obtained by yourself? Never 0 Less than once per week 1 More than once per week 2 (2) Over the last 6 months, for how long have you used drugs prescribed by a doctor? Never 0 For 1 month or less 1 For 1–3 months 2 For more than 3 months 3 From El-Omar EM, Banerjee S, Wirz A, McColl KEL. The Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity Score—a tool for the global measurement of dyspepsia. Eur J GE Hepatol. 1996;8:967–971. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). The score was assessed for validity and reproducibility. The mean score in the general population was 1.16 compared with 10.5 in the nonulcer dyspepsia patients and 11.1 in the duodenal ulcer patients. El-Omar EM, Banerjee S, Wirz A, McColl KEL. The Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity Score—a tool for the global measurement of dyspepsia. Eur J GE Hepatol. 1996;8:967–971. To develop a self-report measure to quantify the severity of dyspepsia symptoms in clinical practice and research. Scale/item Dysmotility-like 1. Frequent burping or belching 4. Bloating 5. Feeling full after meals 6. Inability to finish normal-sized meals 7. Abdominal (belly) discomfort, without pain, after meals 8. Abdominal (belly) distension (feels as though you need to loosen your clothes) 12. Nausea before meals 13. Nausea after meals 14. Nausea when you wake up in the morning 15. Retching (heaving as if to vomit, with little result) 16. Vomiting Reflux-like 3. Burping with bitter tasting fluid in throat 17. Regurgitation of bitter fluid into your mouth (reflux) during the day 18. Regurgitation (reflux) at night 19. Burning feeling in your chest (heartburn) 20. Burning feeling in your stomach Ulcer-like 9. Abdominal (belly) ache or pain right after meals 10. Abdominal (belly) pain before meals or when hungry 11. Abdominal (belly) pain at night Overall item From Leidy NK, Farup C, Rentz AM, Ganoczy D, Koch KL. Patient-based assessment in dyspepsia: Development and validation of dyspepsia symptom severity index (DSSI). Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1172– 1179. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. This is a self-administered questionnaire of 20 items. The numbers in the table state the following order of the items in the questionnaire. The grading of the items by the patient should be on a 0 (absent) to 4 (very severe) Likert scale. One global item is included in order to gather data on the patient’s overall impression of his/her dyspepsia symptom severity. A total score is represented by the mean across the three subscales (dysmotility-, reflux-, and ulcer-like symptoms). Leidy NK, Farup C, Rentz AM, Ganoczy D, Koch KL. Patient-based assessment in dyspepsia: Development and validation of dyspepsia symptom severity index (DSSI). Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1172–1179. The aim was to assess changes in symptom severity in a placebo-controlled trial for patients with functional dyspepsia. This is a patient-completed measure of disease. Severity is scored for each symptom on a 100-mm visual analogue scale. The outcome is defined a priori as the sum of the severity of the eight symptoms, to create the total upper abdominal discomfort severity score (minimum 0, maximum 800 mm). Symptom frequency (from not at all to every day) and impact (from not at all bothersome to extremely bothersome) are scored on five graded Likert scales. Duration (from not at all to continuous or almost continuous) is graded on a seven-graded Likert scale. Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Snape W et al. Failure of a motilin receptor agonist (ABT-229) to relieve the symptoms of functional dyspepsia in patients with and without delayed gastric emptying: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1653–1661. The aim is to assess functional dyspepsia and motor dysfunction by grading six symptoms. Symptom Score Upper abdominal discomfort 0 none 1 mild 2 moderate 3 severe Early satiety 0 none 1 mild 2 moderate 3 severe Postprandial abdominal distension 0 none 1 mild 2 moderate 3 severe Nausea 0 none 1 mild 2 moderate 3 severe Vomiting 0 none 1 mild 2 moderate 3 severe Anorexia 0 none 1 mild 2 moderate 3 severe Total score From Parkman HP, Miller MA, Trate D et al. Electrogastrography and gastric emptying scintigraphy are complementary for assessment of dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24(4):214–219. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). The patient has to grade six symptoms of dyspepsia and upper gastrointestinal motor dysfunction. The score ranges from 0 points (no symptoms) to a maximum of 18 points. Parkman HP, Miller MA, Trate D et al. Electrogastrography and gastric emptying scintigraphy are complementary for assessment of dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24(4): 214–219. The Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire (LDQ) contains eight items. Each with two stems, relating to the frequency and severity of dyspepsia symptoms over the previous 6 months and one item on the most troublesome symptom experienced by the subject. The LDQ gives a range of scores from 0–40, and contains questions on epigastric pain, retrosternal pain, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, belching, early satiety, and dysphagia. The first five questions are used to determine the presence of dyspepsia, whilst all eight questions are required to measure the severity of dyspepsia. The questionnaire is available on request. Moayyedi P, Duffett S, Braunholtz D et al. The Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire: a valid tool for measuring the presence and severity of dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12: 1257–1262. 1 Bothersome postprandial fullness; or Early satiation; or Epigastsric pain or Epigastric burning 2 No evidence of structural disease (including at upper endoscopy) that is likely to explain the symptoms Postprandial Distress Syndrome (PDS) 1 Bothersome postprandial fullness, occurring after ordinary sized meals, at least several times per week; or 2 Early satiation that prevents finishing a regular meal, at least several times per week Supportive Criteria: 1. Upper abdominal bloating or postprandial nausea or excessive belching can be present 2. EPS may co-exist Epigrastric Pain Syndrome (EPS) 1 Pain or burning localized to the epigastrium, or at least moderate severity at least once per week 2 The pain is intermittent 3 Not generalized or localized to other abdominal or chest regions 4 Not relieved by defecation or passage of flatus 5 Not fulfilling criteria for biliary pain 6 The pain may be of a burning quality, but without a retrosternal component 7 The pain is commonly induced or relieved by ingestion of a meal, but may occur while fasting 8 PDS may co-exist Drossman DA. Rome III. The functional gastrointestinal disorders. Lawrence, KW, USA: Allen Press, Inc., 2006. SCS is an eight-question symptom measure developed for use in nonulcer dyspepsia and H. pylori -associated gastritis. The instrument is not specific for dyspepsia and lacks sensitivity. Kuykendall DH, Rabeneck L, Campbell CJ, Wray NP. Dyspepsia: how should we measure it? J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:99–106. Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Tytgat KM, Pollak PT et al. Can severity of symptoms be used as an outcome measure in trials of non-ulcer dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis? J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:273–279. Garratt AM, Ruta DA, Russell I et al. Developing a condition-specific measure of health for patients with dyspepsia and ulcer-related symptoms. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:565–571. Mansi C, Borro P, Giacomini M et al. Comparative effects of levosulpiride and cisapride on gastric emptying and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:561–569. The aim is to grade upper GI symptoms in patients with idiopathic gastroparesis. Symptom None Extreme Postprandial fullness 0 1 2 3 4 Early satiety 0 1 2 3 4 Bloating 0 1 2 3 4 Epigastric discomfort (an ache or discomfort after meals, poorly localized) 0 1 2 3 4 Epigastric pain (a sharp, easy to pinpoint pain after eating) 0 1 2 3 4 Postprandial nausea 0 1 2 3 4 Belching after meals 0 1 2 3 4 Vomiting 0 1 2 3 4 From Miller LS, Szych GA, Kantor SB et al. Treatment of idiopathic gastroparesis with injection of botulinum toxin into the pyloric sphincter muscle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1653–1660. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. A total score is calculated as the sum of each of the eight individual symptom scores. The maximum score is 32. The score correlates with improved solid phase gastric emptying scintigraphy in patients treated with botulinum toxin injection into the pyloric sphincter muscle. Miller LS, Szych GA, Kantor SB et al. Treatment of idiopathic gastroparesis with injection of botulinum toxin into the pyloric sphincter muscle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97: 1653–1660. To develop a medical treatment measure of gastroparesis-related symptoms. This questionnaire asks you about the severity of symptoms you may have related to your gastrointestinal problem. There are no right or wrong answers. Please answer each question as accurately as possible. For each symptom, please circle the number that best describes how severe the symptom has been during the past week. If you have not experienced this symptom, circle 0. If the symptom has been very mild, circle 1. If the symptom has been mild, circle 2. If it has been moderate, circle 3. If it has been severe, circle 4. If it has been very severe, circle 5. Please be sure to answer every question. Please rate the severity of the following symptoms during the past week. The GCSI was developed as part of a larger patient outcomes project for the development of the Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders-Symptom Severity Index (PAGISYM). The GCSI consists of three subscales of the PAGI-SYM instrument, selected to measure important symptoms related to gastroparesis: nausea/vomiting (three items). Postprandial fullness/early satiety (four items) and bloating (two items). A six-point Likert response scale ranging from 0 (none) to 5 (very severe) with a 2-week recall period is used to rate the severity of each symptom. The GCSI total score is constructed as the average of the three symptom subscales. Rentz AM, Schmier J, De La Loge C et al. Development and preliminary psychometric validation of the patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal disorders-symptom severity index (PAGI-SYM) in GI patients. Presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Pharmaco-economics and Outcome Research, Antwerp, Belgium, November 2000. Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Dubois D et al. Development and validation of a patient-assessed gastroparesis symptom severity measure: the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:141–150. Allison performed hiatus herniorrhaphy to prevent reflux esophagitis. Type 1 Sliding hernia. The gastroesophageal junction moves cephalad and may predispose to gastroesophageal reflux Type 2 Pure paraesophageal hernias. The esophagogastric junction is below the diaphragm. The fundus herniates alongside the esophagus through an anterior weakness of the gastrophrenic ligament Type 3 A combination of both a sliding and a paraesophageal defect Type 4 Other viscera including the colon, spleen, small bowel, and omentum herniate through the defect From Allison P. Reflux, esophagitis, sliding hiatal hernia, and the anatomy of repair. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1951;92:419–431. With permission of Elsevier. Type 2 is rare. Type 3 hernias are usually large and repair is advocated regardless of the symptoms because of the potential incarceration. Allison P. Reflux, esophagitis, sliding hiatal hernia, and the anatomy of repair. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1951;92:419–431. A scoring system was created to grade the ability to eat. Score 0 No oral intake 1 Liquids only 2 Soft foods 3 Low residue or full diet From Adler DG, Baron TH. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expanding metal stents: experience in 36 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:72–78. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. This represents a simple grading system for gastric emptying quality. Used for endoscopic treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction. The GOOSS can be applied pre- and poststent placement. Adler DG, Baron TH. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expanding metal stents: experience in 36 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:72–78. Fig. 2.20 Paraesophageal hernia: classification according to Allison. a Type II. b Type III. Gastric volvulus is classified on the basis of the orientation of the rotational axis. Type 1 Organo-axial, the greater curvature rotates anteriorly and superiorly. The rotational axis is the line between the gastro-esophageal junction and pylorus 2 Mesentero-axial, the greater curvature remains in its caudal position, but the pyloroantral region rotates in more of a right-to-left direction. The rotational axis is a line between the midlines of the greater and lesser curvatures 3 Vertical, the rarest type of volvulus, it is a combination of the first and second types Fig. 2.21 Types of gastric volvulus. Reproduced from Wastell C, Ellis H. Volvulus of the stomach. A review with a report of 8 cases. Br J Surg. 1971;58:557–562. With permission granted by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. on behalf of the BJSS, Ltd. The gastric organo-axial volvulus is the most common. The volvulus can be further categorized as: primary or secondary depending on accompanying additional pathologies; as acute or chronic according to its onset; and as intra-thoracic or intra-abdominal according to its location. Determination of the type of volvulus usually is of limited clinical significance, as the tightness and rapidity of the twist are more predictive of eventual gangrene. Wastell C, Ellis H. Volvulus of the stomach. A review with a report of 8 cases. Br J Surg. 1971;58:557–562. The aim is to grade the degree of injury to the stomach. Grade Description I Superficial hematoma; partial thickness laceration II Laceration < 1cm III Laceration 1–5 cm IV Laceration 5–10 cm From Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ, Knudson MM et al. Organ injury scaling. VI: Extrahepatic biliary, esophagus, stomach, vulva, vagina, uterus (nonpregnant), uterus (pregnant), fallopian tube, and ovary. J Trauma. 1995;39:1069–1070. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). This is a useful grading system in abdominal trauma. Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ, Knudson MM et al. Organ injury scaling. VI: Extrahepatic biliary, esophagus, stomach, vulva, vagina, uterus (nonpregnant), uterus (pregnant), fallopian tube, and ovary. J Trauma. 1995;39:1069–1070. To classify gastric varices according to their localization. GEV1 Gastroesophageal varices extending down the lesser curvature, they are more or less straight GEV2 Gastroesophageal varices extending into the fundus of the stomach, they are long and tortuous IGV1 Isolated gastric varices in the fundus (fundal varices) IGV2 Isolated ectopic varices at other sites in the stomach or duodenum GEV, gastroesophageal varix; IGV, isolated gastric varices; EGJ, esophagogastric junction. Fig. 2.22a, b Gastric varices: classification according to Sarin and Kumar. a Gastroesophageal varices. b Isolated gastric varices. Fundal varices (GEV2, IGV1) are more ominous. Tips are less effective in gastric varices compared to esophageal varices. Sarin SK. Long–term follow-up of gastric variceal sclerotherapy: an eleven-year experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:8–14. Sarin SK, Kumar A. Gastric varices: profile, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1244–1249. Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, Murthi NS, Makwane UK. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: long term follow-up study in 568 patients with portal hypertension. Hepatology. 1992;16:1343–1349. The aim was to develop a classification to describe the progression of changes in gastric mucosal lesions during the endoscopic follow-up of portal hypertension. Classification Gastric mucosal changes Nil Normal appearance Mild (i) A fine pink speckling or scarlatina type rash (ii) Superficial reddening, particularly on the surface of the rugae, giving a striped appearance (iii) A fine white reticular pattern separating areas of raised red edematous mucosae resembling a ‘snake skin’ Severe (i) Discrete red spots analogous to the cherry red spots described in the esophagus. These spots can become confluent giving a local area of severe gastritis that may bleed (ii) A diffuse hemorrhagic gastritis From McCormack TT, Sims J, Eyre-Brook I et al. Gastric lesions in portal hypertension: inflammatory gastritis or congestive gastropathy. Gut. 1985;26:1226–1232. With permission of BMJ Publishing Group. Macroscopic gastritis in portal hypertension is unrelated to the etiology of the portal hypertension and it does not respond to conventional anti-inflammatory drug therapy. There is an increased risk of bleeding in severe gastritis (38–62 %) compared with mild cases (3.5–31 %). McCormack TT, Sims J, Eyre-Brook I et al. Gastric lesions in portal hypertension: inflammatory gastritis or congestive gastropathy. Gut. 1985;26:1226–1232. Fig. 2.23a, b Portal hypertensive gastropathy. a Mild. b Severe. The classification was used in a trial that studied the effect of injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices on portal hypertensive gastropathy. Grade I Mild reddening, congestive mucosa, no mosaic-like pattern Grade II Severe redness and a fine reticular pattern separating the areas of raised edematous mucosa (mosaic-like pattern) or a fine speckling Grade III Point bleeding + grade II From Tanoue K, Hashizume M, Wada H, Ohta M, Kitano S, Sugimachi K. Effects of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy on portal hypertensive gastropathy: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38: 582–585. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Portal hypertensive gastropathy worsens after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy. Tanoue K, Hashizume M, Wada H, Ohta M, Kitano S, Sugimachi K. Effects of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy on portal hypertensive gastropathy: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:582–585. To classify elementary endoscopic lesions of portal hypertensive gastropathy, assess their reproducibility, prevalences, sensitivity, and specificity in the diagnosis of cirrhosis of the liver. Mild Areola uniformly pink Moderate Areola has red centre Severe Areola uniformly red Mild Presence of mosaic-like pattern of any severity Severe Presence of mosaic-like pattern and any of the following: 1. Red marks (red point lesions); or 2. Cherry red spots. From Primignani M, Carpinelli L, Preatoni P et al. Natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. The New Italian Endoscopic Club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices (NIEC). Gastroenterology. 2000;119:181–187. With permission of the American Gastroenterological Association. With the New Italian Endoscopic Club classification a sufficient degree of agreement can be achieved in recording portal hypertensive gastropathy. Carpinelli L, Primignani M, Preatoni P et al. Portal hypertensive gastropathy: reproducibility of a classification, prevalence of elementary lesions, sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of cirrhosis of the liver. A NIEC multicentre study. New Italian Endoscopic Club. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;29:533–540. Primignani M, Carpinelli L, Preatoni P et al. Natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. The New Italian Endoscopic Club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices (NIEC). Gastroenterology. 2000;119:181–187. The goals of the Baveno workshops are to develop consensus definitions of key events related to portal hypertension. Parameter Score 1. Mucosal mosaic pattern Mild 1 Severe 2 2. Red markings Isolated 1 Confluent 2 3. Gastric antral vascular ectasia Absent 0 Present 2 From de Franchis R. Developing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 1996;25:390–394. With permission from The European Association for the Study of the Liver. Mild gastropathy = score ≤ 3; severe gastropathy = score ≥ 4. The mosaic pattern consists of small polygonal areas demarcated by a distinct white-to-yellow border, with or without a central bulge. Red marks are flat or slightly bulging red lesions. de Franchis R. Developing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 1996;25:390–394. de Franchls R, ed. Portal Hypertension II. Proceedings of the Second Baveno International Consensus Workshop on Definitions, Methodology and Therapeutic Strategies. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1996. To determine the accuracy of a 2- and a 3-category system for the endoscopic classification of portal hypertensive gastropathy. Mild Fine pink speckling (scarlatina-type rash) Superficial reddening Mosaic pattern Severe Discrete red spots Diffuse hemorrhagic lesion Mild Mild reddening Congestive mucosa Diffuse pink areola Moderate Flat red spot in center of a pink areola Severe redness and a fine reticular pattern separating the areas of raised edematous mucosa Severe Diffusely red areola Pinpoint bleeding Discrete or confluent red mark lesion From Yoo HY, Eustace JA, Verma S et al. Accuracy and reliability of the endoscopic classification of portal hypertensive gastropathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:675–680. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. There is better inter-observer agreement in the 2-category classification. Yoo HY, Eustace JA, Verma S et al. Accuracy and reliability of the endoscopic classification of portal hypertensive gastropathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:675–680. To grade portal hypertensive gastropathy by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Mild Presence of discrete cherry red spots with or without mosaic pattern (small elevated erythematous areas outlined by subtle yellowish network) on the gastric mucosa Severe Presence of confluent red spots, diffusely distributed in a large portion of the stomach with or without active oozing From Sarin SK, Sreenivas DV, Lahoti D, Saraya A. Factors influencing development of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:994–999. With permission of the American Gastroenterological Association. The mucosa of the stomach and the duodenum are inspected carefully especially by bringing the tip of the endoscope close to the mucosa. The precise distribution of portal hypertensive gastropathy in the antrum, corpus, fundus, or whole stomach is recorded. Sarin SK, Sreenivas DV, Lahoti D, Saraya A. Factors influencing development of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1992;102: 994–999. To define the severity of endoscopically detectable mucosal injury induced by aspirin or NSAID’s. 0 Normal 1 One submucosal hemorrhage or superficial ulceration 2 More than one submucosal hemorrhage or superficial ulceration but not numerous or widespread 3 Numerous areas with submucosal hemorrhages or superficial ulcerations 4 Widespread involvement of the stomach with submucosal hemorrhage or superficial ulceration. Invasive ulcer of any size From Lanza FL, Nelson RS, Rack MF. A controlled endoscopic study comparing the toxic effects of sulindac, naproxen, aspirin, and placebo on the gastric mucosa of healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;24:89–95. With permission of Sage Publications. An invasive ulcer is defined as a lesion that produces an actual crater, i. e., a depression below the normal plane of the mucosal surface. The Lanza scale is commonly used to evaluate the mucosal injurious potential of drugs. A score of 3 or 4 represents clinically significant injury. Lanza FL, Nelson RS, Rack MF. A controlled endoscopic study comparing the toxic effects of sulindac, naproxen, aspirin, and placebo on the gastric mucosa of healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;24:89–95. To define the severity of endoscopically detectable mucosal injury induced by aspirin or NSAID’s. 0 No visible injury (i. e. hemorrhages, erosions, or ulcers) 1 Mucosal hemorrhages only (< 10) 2 10–25 hemorrhages and/or 1 to 5 erosions 3 > 25 hemorrhages and/or 6 to 10 erosions 4 > 10 erosions or an ulcer From Lanza FL, Codispoti JR, Nelson EB. An endoscopic comparison of gastroduodenal injury with over-the-counter doses of ketoprofen and acetaminophen. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1051–1054. With permission from the American College of Surgeons. An erosion is defined as a definite discontinuation of the mucosa without depth. An ulcer is defined as any lesion of unequivocal depth. The Lanza scale is commonly used to evaluate the mucosal injurious potential of drugs. A score of 3 or 4 represents clinically significant injury. Lanza FL, Codispoti JR, Nelson EB. An endoscopic comparison of gastroduodenal injury with over-the-counter doses of ketoprofen and acetaminophen. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93: 1051–1054. Fig. 2.24a–c Drug-induced mucosal damage: Lanza Scale. a Drug-induced erosive gastritis (Lanza Grade 1). b Mild drug-induced hemorrhagic gastritis (Lanza Grade 2). c Extensive drug-induced ulceration along the greater curvature (Lanza Grade 4). To define the severity of endoscopically detectable mucosal injury induced by naproxen, and to determine the effect of different scoring systems. 0 Normal stomach 1 Mucosal hemorrhages only 2 One or two erosions 3 Numerous (3–10) areas of erosions 4 Large number of erosions (> 10) or an ulcer 0 No visible lesions 1 One area of hemorrhage 2 More than one, but less than 10 areas of hemorrhage 3 10–25 areas of hemorrhage 4 Hemorrhages in most anatomic areas with more than 25 hemorrhages overall 0 No visible lesions 1 One hemorrhage or erosion (two lesions < 1 cm apart = scored as a single lesion) 2 2–10 hemorrhages or erosions 3 11–25 hemorrhages or erosions 4 More than 25 hemorrhages or erosions, or ulcers of any size From Lanza FL, Graham DY, Davis RE, Rack MF. Endoscopic comparison of cimetidine and sucralfate for prevention of naproxen-induced acute gastro-duodenal injury: Effect of scoring method. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1494–1499. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. Hemorrhages are defined as punctate hemorrhagic lesions that cannot be washed from the mucosa. Erosions and ulcers are defined as white-based mucosal breaks. Erosions are flat and ulcers demonstrate unequivocal depth. The Lanza scale is commonly used to evaluate the mucosal injurious potential of drugs. A score of 3 or 4 represent clinically significant injury. Lanza FL, Graham DY, Davis RE, Rack MF. Endoscopic comparison of cimetidine and sucralfate for prevention of naproxen-induced acute gastro-duodenal injury: Effect of scoring method. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1494–1499. To score upper gastrointestinal mucosal damage in studies comparing COX-2 with nonspecific NSAIDs. Score Appearance of gastric and duodenal mucosae 1 Normal 2 1–10 petechiae 3 > 10 petechiae 4 1–5 erosions 5 6–10 erosions 6 11–25 erosions 7 Ulcer From Simon LS, Lanza FL, Lipsky PE et al. Preliminary study of the safety and efficacy of SC-58635, a novel cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor: efficacy and safety in two placebo-controlled trials in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, and studies of gastrointestinal and platelet effects. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1591–1602. With permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The score is based on the number of petechiae, erosions, and ulcers. An erosion is defined as a lesion producing a definite discontinuance in the mucosa, but without depth. An ulcer is defined as any lesion of any size with unequivocal depth. Simon LS, Lanza FL, Lipsky PE et al. Preliminary study of the safety and efficacy of SC-58635, a novel cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor: efficacy and safety in two placebo-controlled trials in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, and studies of gastrointestinal and platelet effects. Arthritis Rheum. 1998; 41:1591–1602. The aim of this scoring system is to grade macroscopic damage of the gastric mucosa. Score Definition 0 Normal or mucosal erythema 1 Mucosal hemorrhage or edema, without erosions or ulcers 2 One erosion*, with or without hemorrhage or edema 3 Two to four erosions, with or without hemorrhage or edema 4 Five or more erosions, with or without hemorrhage or edema 5 One or more ulcers#, with or without erosion(s), hemorrhage or edema From Cryer B, Feldman M. Effects of very low dose daily, long-term aspirin therapy on gastric, duodenal, and rectal prostaglandin levels and on mucosal injury in healthy humans. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:17–25. With permission of the American Gastroenterological Association. The authors base the scoring on the following premises: (a) hemorrhages and/or edema are abnormal but are less serious than erosions or ulcers; (b) the more erosions, the more injury; and (c) ulcer formation is more serious than even multiple erosions. Cryer B, Feldman M. Effects of very low dose daily, long-term aspirin therapy on gastric, duodenal, and rectal prostaglandin levels and on mucosal injury in healthy humans. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:17–25. Feldman M, Cryer B, Mallat D, Go MF. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastroduodenal injury and gastric prostaglandin synthesis during long term/low dose aspirin therapy: a prospective placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterology. 2001;96:1751–1757. The aim is to grade gastric mucosal appearance in patients with alcoholic gastritis. Grade Description 0 Normal mucosa 1 Marked diffuse hyperemia 2 Single hemorrhagic lesion (≤ 2 mm) 3 2–5 hemorrhagic lesions (≤ 2 mm) 4 6–10 hemorrhagic lesions, partially confluent 5 > 10 hemorrhagic lesions, or large area of confluent hemorrhagic lesions From Tarnawski A, Glick ME, Stachura J, Hollander D, Gergely H. Efficacy of sucralfate and cimetidine in protection of the human gastric mucosa against alcohol injury. Am J Med. 1987;83(Suppl 3B):31–37. With permission from Excerpta Medica Inc. The score was used in a study that evaluated the protective effect of cimetidine and sucralfate on alcoholic gastritis. Tarnawski A, Glick ME, Stachura J, Hollander D, Gergely H. Efficacy of sucralfate and cimetidine in protection of the human gastric mucosa against alcohol injury. Am J Med. 1987;83(Suppl 3B):31–37. This was the first attempt to grade histologic and endoscopic gastric inflammation. The system is summarized in Fig. 2.25. From Tytgat GN. The Sydney System: endoscopic division. Endoscopic appearances in gastritis/duodenitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6: 223–234. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. Commonly used grading system for the evaluation of gastritis. Misiewicz JJ, Tytgat GNJ, Goodwin CS et al. The Sydney system: a new classification of gastritis. In: Working Party Reports, World Congress of Gastroenterology 1990. Sydney: Blackwell Scientific Publications;1990: 1–10. Tytgat GN. The Sydney System: endoscopic division. Endoscopic appearances in gastritis/duodenitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:223–234. Fig. 2.25 Gastritis: grading and staging—the Sydney System. Histological and endoscopic division. To establish an agreed terminology for gastritis, that emphasizes the distinction between the atrophic and nonatrophic stomach. Including a visual analogue (Fig. 2.26) scale improves inter-observer agreement. Biopsies should be taken from the lesser and the greater curvature of the antrum, within 2–3 cm of the pylorus; from the lesser curvature at approximately 4 cm from the angulus; from the greater curvature at approximately 8 cm from the cardia; and from the incisura angularis. Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. Fig. 2.26 Gastritis: the updated Sydney system. Using the visual analogue scales: The observer should attempt to evaluate one feature at a time. The most prevalent appearance on each side should be matched with the grading panel that resembles it most closely. Observers should keep in mind that these drawings are not intended to represent realistically the histopathologic appearance of the gastric mucosa, rather they provide a schematic representation of the magnitude of each feature and, as such, have certain limitations. Thus, for example, the decreasing thickness of the mucosa usually observed with increasing atrophy is not depicted realistically. Particularly with Helicobacter pylori and neutrophils, there may be a considerable variation of intensity within the same biopsy sample. In such cases, the observer should attempt to average the different areas and score the specimen accordingly. Fig. 2.27 Histologic atrophic gastritis with moderate atrophy. Fig. 2.28 Histologic atrophic gastritis with marked atrophy. Fig. 2.29 Histologic atrophic gastritis with marked intestinal meta-plasia. To minimize inter-observer error by proposing a classification that is purely descriptive. Criteria Chronic inflammatory cell infiltration Mild Moderately severe Severe Atrophy Of the glands Of the mucosa as a whole From Rao SS, Krasner N, Thomson TJ. Chronic gastritis—a simple classification. J Pathol. 1975;117:93–96. With permission granted by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd on behalf of The Pathological Society. This classification is based on two descriptive terms that describe the morphological abnormalities of chronic gastritis namely the degree of infiltration of the whole gastric mucosa by inflammatory cells and the presence or absence of atrophy. To this basic classification metaplasia may be added if present. Rao SS, Krasner N, Thomson TJ. Chronic gastritis—a simple classification. J Pathol. 1975;117:93–96. To propose a classification of chronic gastritis, which is applicable to all areas of the gastric mucosa. The score is based on four biopsy features: (1) the mucosal type; (2) the grade of chronic gastritis; (3) the activity of gastritis; and (4) the presence and type of metaplasia. Whitehead R, Truelove SC, Gear MWL. The histological diagnosis of chronic gastritis in fiberoptic gastroscope biopsy specimens. J Clin Pathol. 1972;25:1–11. Whitehead R. Simple (non specific) gastritis. In: Mucosal Biopsy of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Saunders, Philadelphia, London, Toronto 1985:33–85. To define a grading that is based on the loss of glands, regardless of the presence of inflammatory signs or metaplasia. Grade 0. Normal mucosa No round cell infiltration, no loss of glands 1. Superficial gastritis Round cell infiltration without loss of glands 2. Slight atrophic gastritis Slight loss of glands 3. Moderate atrophic gastritis Moderate loss of glands 4. Severe atrophic gastritis Severe loss of glands From Kekki M, Siurala M, Varis K, Sipponen P, Sistonen P, Nevanlinna HR. Classification principles and genetics of chronic gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22(Suppl 141), 1–28. By permission of Taylor & Francis AS. The scoring system is simple and equally applicable to both antral and body gastritis. Kekki M, Siurala M, Varis K, Sipponen P, Sistonen P, Nevanlinna HR. Classification principles and genetics of chronic gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22(Suppl 141):1–28. Siurala M, Sipponen P, Kekki M. Chronic gastritis: dynamic and clinical aspects. Scan J Gastroenterol. 1985;20(Suppl 109): 69–76. The aim of this classification is to define the quality and extent of inflammatory-atrophic changes of the gastric mucosa. Not atrophic Superficial (SG) Band-like infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells occupying the superficial portion of the gastric mucosa, mostly at the gastric pits (foveola) and the necks. Association with spicy food, alcohol, analgesics, and C. pylori. Diffuse antral (DAG) A dense infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells occupying full thickness of the antral mucosa. The infiltrate expands the lamina propria and separates the gastric glands. Lymphoid follicles may be prominent. Association with duodenal or pyloric peptic ulcers. Atrophic Diffuse corporal (DCG) A diffuse loss of the oxyntic glands (corpus and fundus). Part of pernicious anemia syndrome. Multifocal atrophic (MAG) Correlation with population at risk of stomach cancer. Independent foci of atrophy (gland loss) and mononuclear infiltrate that decreases with intensity as atrophy progresses. Topographic distribution is age-dependant. From Correa P. Chronic gastritis: a clinico-pathologic classification. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;2:779–780. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. This is a commonly used system to grade gastric inflammation and atrophy. The qualification “acute injury” can be added to any lesion, indicating: polymorphonuclear infiltrate, depletion of cytoplasmic mucus in the foveolar cells, and a mild degree of architectural distortion of the foveolar portion of the mucosa. Correa P. Chronic gastritis: a clinico-pathologic classification. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;2:779–780. To grade endoscopically the extent of atrophy in the stomach. Type C–0 No atrophic changes C–1 Atrophic changes only in the antrum C–2 Atrophic border on the lesser curvature of the lower portion of the body C–3 Atrophic border on the lesser curvature of the upper portion of the body O–1 Atrophic border lies on the lesser curvature and anterior wall of the body O–2 Atrophic border lies on the anterior wall of the body O–3 The atrophic region spreads between the anterior wall and the greater curvature of the body O–p Pangastritis, atrophic region throughout the entire stomach Fig. 2.30 Atrophic gastritis: classification according to Kimura and Takemoto, closed and open type. The atrophic border is the boundary between the pyloric and fundic gland territories. It is recognized endoscopically by the difference in color and height of the mucosa. Biopsies should be taken at the following four sites: (Site 1) the lesser curvature of the mid antrum; (Site 2) the lesser curvature of the angulus; (Site 3) the lesser curvature of the mid body (at a position midway between the angulus and the esophagogastric junction); (Site 4) the greater curvature of the mid body (at a position between the entrance to the antrum and the boundary between the corpus and the fornix). Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87–97. Satoh K, Kimura K, Taniguchi Y et al. Distribution of inflammation and atrophy in the stomach of Helicobacter pylori -positive and -negative patients with chronic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:963–969. To establish a universal, easily applicable grading system. Findings Grade Definition Surface irregularity 1 Fine granular change 2 Uniform granular change 3 Granular change with various sizes Rugal hypertrophy 1 Partial 2 Entire 3 More than 10 mm in width Visibility of vascular pattern 1 Partial 2 Uniform and continuous 3 Blood vessels rising to the surface Intestinal metaplasia 1 Solitary 2 Multiple but localized 3 Diffuse Spotty erythema 1 Localized 2 Widely scattered 3 Widely and densely presented Patchy erythema 1 Scattered 2 Densely presented 3 Mixed with fused redness Linear erythema 1 Intermittent 2 Continuous 3 Wide with erosion or bleeding Edema 1 Glossy 2 With exudate 3 Wide Flat or depressed erosion 1 Solitary 2 Multiple but localized 3 Multiple and widely presented Raised erosion 1 Solitary 2 Scattered (< 5 lesions) 3 Multiple (> 6 lesions) Hemorrhage 1 Solitary 2 Multiple but localized 3 Diffuse Fig. 2.31a–c Surface irregularity. a Grade 1: fine granular change. b Grade 2: uniform granular change. c Grade 3: granular change with various sizes. Fig. 2.32a–c Rugal hyperplasia. a Grade 1: partial. b Grade 2: entire. c Grade 3: > 10 mm wide. Fig. 2.33a–c Visibility of vascular pattern. a Grade 1: partial. b Grade 2: uniform and continuous. c Grade 3: blood vessels rising to the surface. Fig. 2.34a–c Intestinal metaplasia. a Grade 1: solitary. b Grade 2: multiple but localized. c Grade 3: diffuse. Fig. 2.35a–c Spotty erythema. a Grade 1: localized. b Grade 2: widely scattered. c Grade 3: widely and densely presented. Fig. 2.36a–c Patchy erythema. a Grade 1: scattered. b Grade 2: densely presented. c Grade 3: mixed with fused redness. Fig. 2.37a–c Linear erythema. a Grade 1: intermittent. b Grade 2: continuous. c Grade 3: wide with erosion or bleeding. Fig. 2.38a–c Edema. a Grade 1: glossy. b Grade 2: with exudates. c Grade 3: wide. Fig. 2.39a–c Flat or depressed erosion. a Grade 1: solitary. b Grade 2: multiple but localized. c Grade 3: multiple and widely presented. Fig. 2.40a–c Raised erosion. a Grade 1: solitary. b Grade 2: scattered (< 5 lesions). c Grade 3: multiple (> 6 lesions). Fig. 2.41a–c Hemorrhage. a Grade 1: solitary. b Grade 2: multiple but localized. c Grade 3: diffuse. Fundamental types Code number Definition according to endoscopic findings Superficial gastritis 1 Findings including edema and redness (spotted, patchy, linear) are observed Hemorrhagic gastritis 2 Hemorrhage is evidenced Erosive gastritis 3 Erosive changes including flat or depressed types Verrucous gastritis 4 Erosive changes including elevated type Atrophic gastritis 5 Findings such as color change of mucosa, visible vascular pattern, and thinning are observed Metaplastic gastritis 6 Intestinal metaplasia is noted Hyperplastic gastritis 7 Remarkable irregularity of mucosa or rugal hypertrophy of greater curvature in corpus Special gastritis 8 Any types not included in the seven fundamental types, for example, granulomatous gastritis, eosinophilic gastritis, lymphocytic gastritis, Ménétrier disease, and amyloidosis Superficial gastritis Atrophy and inflammation are hardly observed in glands with observation of inflammatory cell infiltration only at the surface of mucosa Hemorrhagic gastritis Hemorrhage, hemosiderin sedimentation, hemosiderin phagocytic macrophage are observed Erosive gastritis Defect of superficial mucosa is observed, with relevant bioresponse (fibrin precipitation, hemorrhage, edema, neutrophil infitration, and growth of capillary) being evidenced Verrucous gastritis This is in the state of hyper-regeneration after erosion, with irregular running of muscle fibers of muscularis mucosae and hyperplasia of pyloric glands surrounded by myofibers in the area of pyloric glands, as well as replacement of pseudopyloric glands and alterations in regeneration of foveolar epithelium Atrophic gastritis Atrophy of glands is observed Metaplastic gastritis In the biopsy specimens, intestinal metaplastic tubule is observed in more than ⅓ of mucosal tissues Hypertrophic gastritis Hypertrophy of glands is observed while foveolar epithelium is almost normal or hypertrophic From Kaminishi M, Yamaguchi H, Nomura S et al. Endoscopic classification of chronic gastritis based on a pilot study by the research society for gastritis. Digestive Endoscopy. 2002;14:138–151. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. The use of five basic types of gastritis is advised: superficial, erosive, verrucous, atrophic, and special types. Metaplastic and hyperplastic types should be excluded from the fundamental types; however, they might be additionally described if they are significant. Kaminishi M, Yamaguchi H, Nomura S et al. Endoscopic classification of chronic gastritis based on a pilot study by the research society for gastritis. Digestive Endoscopy. 2002;14: 138–151. Intestinal metaplasia is classified into three types based on the histochemical detection of mucins. Type Description I Complete Straight crypts and regular architecture. The epithelium consists of mature absorptive cells and goblet cells. Goblet cells secrete sialomucin. The absorptive cells are nonsecretory and have well-formed brush borders. Paneth cells are often present. II Incomplete without sulphomucins Crypts are elongated and tortuous with mild architectural distortion. The epithelium has few or no absorptive cells, and there are columnar cells in various stages of differentiation. These cells secrete neutral mucin and/or small amounts of sialomucin. Goblet cells secrete sialomucin and occasionally sulphomucins. Paneth cells are rarely present. III Incomplete with sulphomucins Distortion of glandular architecture is more pronounced, with cell atypia and loss of differentiation. More marked than in type II. Columnar cells secrete predominantly sulphomucins, and goblet cells contain sialo- and/or sulphomucins. Paneth cells are usually absent. Fig. 2.42a–c Intestinal metaplasia: classification according to Jass and Filipe. a Type I. b Type III. From Jass JR, Filipe MI. The mucin profiles of normal gastric mucosa, intestinal metaplasia and its variants and gastric carcinoma. Histochem J. 1981;13:931–939. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. Small intestinal goblet cells produce sialoglycoproteins that stain with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and alcian blue (AB). Colonic goblet cells produce sulphomucin that is detected by AB/high-iron diamine (HID) staining. Progression from type I to type III is proposed during the development of gastric cancer. Filipe IM, Ramachandra S. The histochemistry of intestinal mucins; changes in disease. In: Whitehead R, ed. Gastrointestinal and Oesophageal Pathology, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:73–95. Jass JR, Filipe MI. The mucin profiles of normal gastric mucosa, intestinal metaplasia and its variants and gastric carcinoma. Histochem J. 1981;13:931–939. The aim of this classification is to characterize intestinal meta-plasia. Complete type Intestinal metaplasia associated with the intestinal marker enzymes sucrose alpha-D-glucohydrolase, alpha, alpha-trehalase, aminopeptidase (microsomal) (APM), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Tissue of this type contains goblet cells and Paneth’s cells, but does not show high-iron diamine (HID)-positive mucin staining with HID-Alcian blue. Incomplete type Intestinal metaplasia associated with sucrose alpha-D-glucohydrolase, APM, goblet cells, and HID-positive mucin but not with alpha, alpha-trehalase, ALP, or Paneth’s cells. From Matsukura N, Suzuki K, Kawachi T et al. Distribution of marker enzymes and mucin in intestinal metaplasia in human stomach and relation to complete and incomplete types of intestinal metaplasia to minute gastric carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;65:231–240. With permission of Oxford University Press. Gastrointestinal metaplasia is divided into complete (small intestinal) and incomplete (colonic) varieties using enzyme expression. Metaplastic tissue that secretes sulphomucins is known to accompany intestinal type gastric cancer. Matsukura N, Suzuki K, Kawachi T et al. Distribution of marker enzymes and mucin in intestinal metaplasia in human stomach and relation to complete and incomplete types of intestinal metaplasia to minute gastric carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;65:231–240. To classify gastric ulcers depending on the distribution in the stomach. Type 1 Ulcers are located at the level of the angular notch, or above. This is usually in the area of the antrocorporeal transitional zone, which may rise along the lesser curve as a function of age. 2 Ulcers are in the same location, but occur in association with evidence of actual or prior duodenal ulcer disease. 3 Ulcers are in the prepyloric region, usually within 2.5 cm of the pylorus. From Johnson HD. Gastric ulcer: classification, blood group characteristics, secretion pattern and pathogenesis. Ann Surg. 1965;162: 996–1004. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). Type I ulcers are associated with low or normal acid secretion, whereas types II and III have high acid secretion. Johnson HD. Gastric ulcer: classification, blood group characteristics, secretion pattern and pathogenesis. Ann Surg. 1965;162:996–1004. The aim was to describe the various stages of healing of gastric ulcers. Phase A1 Active stages Ulcer that contains mucus coating, with marginal elevation because of edema A2 Mucus-coated ulcer with discrete margin and less edema than active stage 1 H1 Healing stages Unhealed ulcer covered by regenerating epithelium less than 50%, with or without converging folds H2 Ulcer with a mucosal break but almost covered with regenerating epithelium S1 Scar stages, red scar Red scar with rough epithelialization without mucosal break S2 Scar stages, white scar White scar with complete reepithelialization Fig. 2.43 The various phases of healing of a gastric ulcer (adapted from Sakita and Fukutomi. A1, A2: active stages; H1, H2: healing stages; S1, S2: scar stages (red scar, white scar). From Lee SY, Kim JJ, Lee JH et al. Healing rate of EMR-induced ulcer in relation to the duration of treatment with omeprazole. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:213–217. With permission from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. This system is often used in Japan. Lee SY, Kim JJ, Lee JH et al. Healing rate of EMR-induced ulcer in relation to the duration of treatment with omeprazole. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:213–217. Sakita T, Fukutomi H. Endoscopy of gastric ulcer. In: Yoshitoshi Y, ed. Peptic Ulcer. Tokyo: Nonkodo; 1971:198–208. To evaluate patient symptoms after peptic ulcer surgery. Grade I No symptoms Grade II Mild symptoms relieved by care Grade III s Mild symptoms not relieved by care, but satisfactory Grade III u Mild symptoms not relieved by care, unsatisfactory Grade IV Not improved From Visick AH. A study of failures after gastrectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1948;3:266–284. With permission of The Royal College of Surgeons of England. Grades I and II are usually considered a satisfactory outcome. “Relieved by care” is poorly specified. Visick AH. A study of failures after gastrectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1948;3:266–284. Goligher JC, Hill GL, Kenny TE, Nutter E. Proximal gastric vagotomy without drainage for duodenal ulcer—results after 5–8 years. Br J Surg. 1978;3:145–151. Type % of cases 1 Afferent limb intussusception 6 2a Efferent limb intussusception 70–75 combined 2b Afferent-efferent limb intussusception 3 A combination of type 1 and 2 10 4 Intussusception through a Braun side-to-side jejunojejunal anastomosis Fig. 2.44 Classification of jejunogastric intussusception according to Michael. From Michael JW. Jejunogastric intussusception diagnosis and management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:452–453. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). The jejunogastric intussusception is a rare complication of gastric surgery. Michael JW. Jejunogastric intussusception diagnosis and management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:452–453. Three anatomic types of jejunogastric intussusception are described. Type % of cases 1 Antegrade or afferent limb intussusception 10 2 Retrograde or efferent limb intussusception 80 3 A combination of type 1 and 2 10 From Shackman R. Jejunogastric intussusception. Br. J. Surg. 1940;27: 475–480. With permission granted by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. on behalf of the BJSS, Ltd. The jejunogastric intussusception is a rare complication of gastric surgery. Retrograde peristalsis seems to be the cause of type II intussusception. Shackman R. Jejunogastric intussusception. Br. J. Surg. 1940;27:475–480. To categorize gastric polypoid lesions according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) histologic classification of gastrointestinal tumors was revised in 1990. Neoplasia a. Epithelial Intestinal-type adenoma – Tubular – Tubulovillous – Villous Pyloric gland adenoma Adenocarcinoma b. Endocrine Carcinoid tumor c. Mesenchymal Leiomyoma Neurogenic tumors – Neurinoma, neurofibroma Granular cell tumor Lipoma Sarcoma – Neurosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, – Leiomyosarcoma d. Lymphatic Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma Tumorlike lesion Fundic gland polyp Hyperplastic polyp Inflammatory fibroid polyp Brunner’s gland heterotopia Pancreatic heterotopia Peutz–Jeghers polyp Cronkhite–Canada polyp Juvenile polyp Differential diagnosis Focal foveolar hyperplasia Lymphatic follicles Giant folds Varioliform gastritis From Watanabe H, Jass JR, Sobin LH. Histological Typing of Esophageal and Gastric Tumors. Berlin: Springer; 1990. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. According to the WHO classification of gastric tumors and polyps the frequency of malignant transformation depends on histologic type. Jass JR, Sobin LH, Watanabe H. The World Health Organization’s histologic classification of gastrointestinal tumors. A commentary on the second edition. Cancer. 1990;66: 2162–2167. Watanabe H, Jass JR, Sobin LH. Histological Typing of Esophageal and Gastric Tumors. Berlin: Springer; 1990. To propose a useful classification of gastric polyps. Nonneoplastic polyps A. Possibly inflammatory 1. Hyperplastic polyp (synonyms: regenerative polyp, reparative polyp, polyp type I and II of Nakamura) 2. Inflammatory fibroid polyp 3. Gastric xanthelasma B. Possibly hamartomatous 1. Peutz–Jeghers polyp 2. Juvenile polyp 3. Cronkhite–Canada polyp 4. Fundic gland polyp (synonyms: retention polyp, cystic polyp, Elster’s glandular cysts) a. Associated with familial adenomatous polyposis b. Not associated with familial adenomatous polyposis C. Heterotopia-pancreatic rest (synonyms: adenomyoma, adenomyomatous hamartoma) Neoplastic polyps A. Adenoma with or without associated carcinoma 1. Tubular (usually flat) 2. Tubulovillous 3. Villous B. Lymphoma C. Carcinoid The most common polyps are fundic gland polyps, hyperplastic polyps, and adenomas. Petras RE. Comments on the Proceedings of the Endoscopy Masters Forum: endoscopy in the precancerous and early-stage cancerous conditions of the gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 1995;27:58–63. To achieve consensus in the classification of gastric dysplasia between the Japanese and the Western system. Category Microscopic image 1 Negative for neoplasia/dysplasia 1.0 Normal 1.1 Reactive foveolar hyperplasia 1.2 Intestinal metaplasia (IM) 1.2.1 IM complete type 1.2.2 IM incomplete type 2 Indefinite for dysplasia 2.1 Foveolar proliferation 2.2 Hyperproliferative IM 3 Noninvasive neoplasia [flat or elevated (synonymous with adenoma)] 3.1 Low grade 3.2 High grade 3.2.1 Including suspicious for carcinoma without invasion (intra-glandular) 3.2.2 Including carcinoma without invasion (intra-glandular) 4 Suspicious for invasive carcinoma 5 Invasive adenocarcinoma From Rugge M, Correa P, Dixon MF et al. The Padova classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:167–176. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). Categories 1 and 2 are considered benign alterations. Rugge M, Correa P, Dixon MF et al. The Padova classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:167–176. For the grading of gastric neoplasia please also see the Vienna Classification, the modified Vienna classification, and the WHO classification schemes discussed in Chapter 1, Neoplastic Disorders, pages 57–59. This is a recommendation on reporting gastric biopsies proposed by the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer. Group I Normal mucosa and benign lesions with no atypia Group II Lesions showing atypia but not diagnosed as benign (nonneoplastic) Group III Borderline lesions between benign (nonneoplastic) and malignant lesions Group IV Lesions strongly suspected of being carcinoma Group V Carcinoma From Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer. Group classification of gastric biopsy specimens. In: Nishi M, Omori Y, Miwa K, eds. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. Tokyo: Kanehara; 1995: 73–76. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. Influenced by the early histologic studies on gastric neoplasia by Nakamura et al., the JRSGC guidelines propose five groups, ranging from normal mucosa to carcinoma that is not necessarily infiltrating. Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer. Group classification of gastric biopsy specimens. In: Nishi M, Omori Y, Miwa K, eds. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. Tokyo: Kanehara; 1995:73–76. Nakamura K, Sugano H, Takagi K, Fuchigami A. Histopathological study on early carcinoma of the stomach: criteria for diagnosis of atypical epithelium. Gann. 1966;57:613–620. To classify early and advanced gastric cancer based on endoscopic appearance. Type 0-I Protruding type Type 0-IIa Superficial elevated type Type 0-IIb Flat type Type 0-IIc Superficial depressed type Type 0-III Excavated type Type 1: Polypoid tumors, sharply demarcated from the surrounding mucosa, usually attached on a wide base Type 2: Ulcerated carcinomas with sharply demarcated and raised margins Type 3: Ulcerated carcinomas without definite limits, infiltrating into the surrounding wall Type 4: Diffusely infiltrating carcinomas in which ulceration is usually not a marked feature Type 5: Nonclassifiable carcinomas that cannot be classified into any of the above types From Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 2nd English ed. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. When there is a combination of types of early gastric cancer, the type that occupies the largest area should be described first. In the case where the lesion has twice the thickness of normal mucosa, it should be typed 0-I. If it has less than twice the thickness of normal mucosa, it should be typed 0-IIa. Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 1st English ed. Tokyo: Kanehara; 1995:73–88. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 2nd English ed. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1: 10–24. Fig. 2.45 Endoscopic classification of early gastric carcinoma. Type I: protruded; Type II: superficial (IIa: elevated; IIb: flat; IIc: depressed); type III: excavated (Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer). To stage various presentations of advanced gastric cancer. Type I A polypoid cauliflower-like mass projecting into the gastric lumen, without substantial necrosis or ulceration II Ulcerated mass or fungating lesion with sharp margin. Cancerous tissue is present in the periphery and in the center of the ulceration III Diffusely infiltrating type, with superimposed ulcerations, lesions often have indistinct margins IV Diffuse infiltrating linitis plastica-type malignancy From Borrmann R. Geschwulste des Magens und Duodenum. In: Henke F, Lubarch O, eds. Handbuch der speziellen pathologischen Anatomie und Histologie. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1926. With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. This grading system is still occasionally used. Borrmann R. Geschwulste des Magens und Duodenum. In: Henke F, Lubarch O, eds. Handbuch der speziellen pathologischen Anatomie und Histologie. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1926. Fig. 2.46 The classification of advanced gastric cancer with four categories, according to Borrmann. Fig. 2.47a–d a Borrmann type I gastric adenocarcinoma. b Borrmann type II lesion. c Borrmann type III lesion, with superimposed ulceration. d Borrmann type IV lesion, with diffusely infiltrating carcinoma. TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed T0 No evidence of primary tumor Tis Carcinoma in situ: intra-epithelial tumor without invasion of the lamina propria T1 Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa T2 Tumor invades muscularis propria or submucosa T2a Tumor invades muscularis propria T2b Tumor invades subserosa T3 Tumor penetrates serosa (visceral peritoneum) without invasion of adjacent structures T4 Tumor invades adjacent structures NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed N0 No regional lymph node metastasis N1 Metastasis in 1 to 6 regional lymph nodes N2 Metastasis in 7 to 15 regional lymph nodes N3 Metastasis in more than 15 regional lymph nodes MX Presence of distant metastasis cannot be assessed M0 No distant metastasis M1 Distant metastases GX Grade cannot be assessed G1 Well differentiated G2 Moderately differentiated G3 Poorly differentiated G4 Undifferentiated RX Presence of residual tumor cannot be assessed R0 No residual tumor R1 Microscopic residual tumor R2 Macroscopic residual tumor From Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer, 2002. Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed (2002) published by Springer-New York, www.springeronline.com. The AJCC TNM staging system uses three basic descriptors that are then grouped into stage categories. The first component is “T,” which describes the extent of the primary tumor. The next component is “N,” which describes the absence or presence and extent of regional lymph node metastasis. The third component is “M,” which describes the absence or presence of distant metastasis. The final stage groupings (determined by the different permutations of “T,” “N,” and “M”) range from Stage 0 through Stage IV. Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer, 2002. http://www.cancerstaging.org/. To provide a common language for the clinical and pathologic description of gastric carcinoma. T1: Tumor invasion of mucosa and/or muscularis mucosa (M) or submucosa (SM) T2: Tumor invasion of muscularis propria (MP) or subserosa (SS) T3: Tumor penetration of serosa (SE) T4: Tumor invasion of adjacent structures (SI) TX: Unknown No. 1 Right paracardial LN No. 2 Left paracardial LN No. 3 LN along the lesser curvature No. 4sa LN along the short gastric vessels No. 4sb LN along the left gastroepiploic vessels No. 4d LN along the right gastroepiploic vessels No. 5 Suprapyloric LN No. 6 Infrapyloric LN No. 7 LN along the left gastric artery No. 8a LN along the common hepatic artery (anterosuperior group) No. 8p LN along the common hepatic artery (posterior group) No. 9 LN around the celiac artery No. 10 LN at the splenic hilum No. 11p LN along the proximal splenic artery No. 11d LN along the distal splenic artery No. 12a LN in the hepatoduodenal ligament (along the hepatic artery) No. 12b LN in the hepatoduodenal ligament (along the bile duct) No. 12p LN in the hepatoduodenal ligament (behind the portal vein) No. 13 LN on the posterior surface of the pancreatic head No. 14v LN along the superior mesenteric vein No. 14a LN along the superior mesenteric artery No. 15 LN along the middle colic vessels No. 16a1 LN in the aortic hiatus No. 16a2 LN around the abdominal aorta (from the upper margin of the celiac trunk to the lower margin of the left renal vein) No. 16b1 LN around the abdominal aorta (from the lower margin of the left renal vein to the upper margin of the inferior mesenteric artery) No. 16b2 LN around the abdominal aorta (from the upper margin of the inferior mesenteric artery to the aortic bifurcation) No. 17 LN on the anterior surface of the pancreatic head No. 18 LN along the inferior margin of the pancreas No. 19 Infradiaphragmatic LN No. 20 LN in the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm No. 110 Paraesophageal LN in the lower thorax No. 111 Supradiaphragmatic LN No. 112 Posterior mediastinal LN Fig. 2.48a–d Japanese staging of gastric carcinoma: lymph node groups. N0 No evidence of lymph node metastasis N1 Metastasis to Group 1 lymph nodes, but no metastasis to Groups 2 or 3 lymph nodes N2 Metastasis to Group 2 lymph nodes, but no metastasis to Group 3 lymph nodes N3 Metastasis to Group 3 lymph nodes NX Unknown D0 No dissection or incomplete dissection of the Group 1 nodes D1 Dissection of all the Group 1 nodes D2 Dissection ofall the Group 1 and Group 2 nodes D3 Dissection of all the Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3 nodes From Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 2nd English ed. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24.With kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. http://www.jgca.jp/PDFfiles/JCGC-2E.PDF. This is a classification of gastric cancer proposed in 1965 by Lauren that divides gastric cancer into either intestinal or diffuse forms. Type Description Intestinal Differentiated cancer with a tendency to form glands. More likely to involve the distal stomach and to occur in patients with atrophic gastritis. Strong environmental association. Diffuse There is little cell cohesion and there is a predilection for extensive submucosal spread and early metastasis. May involve any part of the stomach and has worse prognosis. Has similar frequency in all geographic areas. Others The Laurén classification is a useful classification for epidemiological studies. It only roughly stratifies gastric carcinoma into three histopathologic types, and has little prognostic relevance. Laurén P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal type carcinoma. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31-49. To propose a simple biological classification, which divides gastric carcinoma into two types: the expanding and the infiltrative type. Features Expanding carcinoma Infiltrative carcinoma Pathologic features 1. Cell Glandular pattern Common Rare Cell differentiation Variable Variable Cell aggregation Common Border of aggregate Distinct Indistinct Cell density Dense Loose Goblet cell Common Common Striated border Common Rare 2. Mucus Acidic mucus Common Common Extra-cellular pool Occasional Frequent 3. In situ carcinoma Common Rare 4. Stroma Collagenous tissue Moderate Marked Lymphocytes, plasmocytes Common Rare 5. Surrounding tissue Compressed Not compressed 6. Adjacent mucosa Intestinal metaplasia Severe Mild Dysplasia Common Absent Clinical features 1. Sex (male:female) 2:1 1:1 2. Age, under 50 years 6% 14% 3. 5-year survival 27.4% 9.9% Reproduced from Ming SC. Gastric carcinoma, a pathological classification. Cancer. 1977;39:2475-2485. With permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. There is a close correspondence between the classification of Laurén and Ming, where intestinal-type cancer has features of expanding carcinoma and diffuses type cancer resembles infiltrative carcinoma. Ming SC. Gastric carcinoma, a pathological classification. Cancer. 1977;39:2475-2485. Stemmermann GN, Brown C. A survival study of intestinal and diffuse types of gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1974;33: 1190-1195. To create a histologic classification of gastric cancer based on the degree of differentiation of the glandular tubules and the amount of mucus in the cytoplasm. Type Tubular differentiation Mucus in cytoplasm I Well Poor II Well Rich III Poor Poor IV Poor Rich Fig. 2.49 Gastric carcinoma: Classification according to Goseki. From Goseki N, Takizawa T, Koike M. Differences in the mode of the extension of gastric cancer classified by histological type: new histological classification of gastric carcinoma. Gut. 1992;33:606-612. With permission of BMJ Publishing Group. The frequency of hematogenous metastasis is high in group I. In group IV the frequency of lymph node metastasis, direct invasion into surrounding organs, and peritoneal dissemination is higher. Dixon MF, Martin IG, Sue-Ling HM, Wyatt JI, Quirke P, Johnston D. Goseki grading in gastric cancer: comparison with existing systems of grading and its reproducibility. Histopathology. 1994;25:309-316. Goseki N, Takizawa T, Koike M. Differences in the mode of the extension of gastric cancer classified by histological type: new histological classification of gastric carcinoma. Gut. 1992;33:606-612. The aim of this classification is to classify gastric carcinoma based upon histologic type. The Carneiro classification recognizes four histologic types: glandular, isolated cells, solid glandular, and mixed glandular type. There are differences in the biological behavior of gland forming and isolated cell gastric carcinomas. Mixed carcinoma has an isolated cell component and another component. Diagnosis may be difficult as the presence of a second component in the tumor occupying 5% of its volume may change the classification. Mixed carcinoma has the worst prognosis. Carneiro F, Seixas M, Sobrinho-Simoes M. New elements for an updated classification of the carcinomas of the stomach. Pathology, Research and Practice. 1995;191:571-584. The aim of the classification is to stage gastric cancer according to the dominant histologic abnormality. The WHO classification of gastric carcinoma defines six types: papillary, tubular, mucinous, signet-ring cell, undifferentiated, and others. The WHO classification presents histologically well-described tumor categories. However, it is a purely descriptive classification that has very little relationship to prognosis and biological behavior. Fenoglio-Preiser C, Carneiro F, Correa P et al. Gastric carcinoma. In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, eds. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. WHO Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2000:39-52. To classify esophagogastric tumors based on the anatomic location of the tumor center. Type I Adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus, which usually arises from an area with specialized intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus (i. e., Barrett esophagus) and may infiltrate the esophagogastric junction from above Type II True carcinoma of the cardia arising immediately at the esophagogastric junction Type III Subcardial gastric carcinoma that infiltrates the esophagogastric junction and distal esophagus from below From Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Carcinoma of the cardia: carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction—classification, pathology and extent of resection. Dis Esophagus. 1996;9:173-182. With permission of Blackwell Publishing. This classification was approved at a consensus conference of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus in 1997. The authors treat type I tumors as esophageal cancer and type II and III tumors as gastric cancer. Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Carcinoma of the cardia: carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction—classification, pathology and extent of resection. Dis Esophagus. 1996;9:173-182. Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br JSurg. 1998;85:1457-1459. To stage gastric MALT lymphoma. Grade Description Histologic features 0 Normal Scattered plasma cells in lamina propria. No lymphoid follicles. 1 Chronic active gastritis Small clusters of lymphocytes in lamina propria. No lymphoid follicles. No lymphoepithelial lesions. 2 Chronic active gastritis with florid lymphoid follicle formation Prominent lymphoid follicles with surrounding mantle zone and plasma cells. No lymphoepithelial lesions. 3 Suspicious lymphoid infiltrate in lamina propria, probably reactive Lymphoid follicles surrounded by small lymphocytes that infiltrate diffusely in lamina propria and occasionally into epithelium. 4 Suspicious lymphoid infiltrate in lamina propria, probably lymphoma Lymphoid follicles surrounded by centrocyte-like cells that infiltrate diffusely in lamina propria and into epithelium in small groups. 5 Low-grade B-cell lymphoma of MALT Presence of dense diffuse infiltrate of centrocyte-like cells in lamina propria with prominent lymphoepithelial lesions. From Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. With permission of Elsevier. Most H. pylori associated low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, limited to the gastric wall in the absence of regional lymph node involvement, do respond to antimicrobial therapy. Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. A post-treatment histologic grading system for gastric MALT lymphoma was established as part of a multicenter clinical study. The GELA grading is a post-treatment histologic grading based on H&E stained sections of three essential diagnostic features: the lymphoid infiltrate, the presence of lymphoepithelial lesions, and stromal changes. Copie-Bergman C, Gaulard P, Lavergne-Slove A et al. Proposal for a new histological grading system for post-treatment evaluation of gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut. 2003;52:1656. The aim is to grade the regression of gastric MALT lymphoma. Complete histologic regression No remnant lymphoma cells can be detected in the post-treatment biopsy specimens and an “empty” tunica propria with small basal clusters of lymphocytes and scattered plasma cells are found instead Partial histologic regression Defined by the presence of post-treatment biopsy samples exhibiting only partial depletion of atypical lymphoid cells from the tunica propria or focal lymphoepithelial destruction From Neubauer A, Thiede C, Morgner A et al. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection and duration of remission of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1350–1355. With permission of Oxford University Press. The regression of gastric MALT lymphoma after H. pylori eradication is assessed by endoscopic biopsies. Isaacson PG. Gastrointestinal lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 1994;25: 1020–1029. Neubauer A, Thiede C, Morgner A et al. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection and duration of remission of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1350–1355. This classification is an attempt to classify hyperplastic and neoplastic endocrine cell changes in the stomach by arranging them in a sequence of morphological lesions with increasing oncological potential. Normal pattern Normal number and distribution of endocrine cells Hyperplasia Simple (diffuse) hyperplasia Linear or chain-forming hyperplasia Micronodular hyperplasia Adenomatoid hyperplasia Dysplasia Dysplastic (precarcinoid) growth – Enlarging micronodule – Fusing micronodules – Microinvasive lesion – Nodule with newly formed stroma Neoplasia Intra-mucosal neoplasia (intra-mucosal carcinoid) Invasive neoplasm (invasive carcinoid) Fig. 2.50a–f Gastroendocrine cell classification according to Solcia. a Simple (diffuse) hyperplasia. b Linear or chain-forming hyperplasia. c Micronodular hyperplasia. d Enlarging micronodule. e Intramucosal neoplasm. f Invasive neoplasm. As a cut-off point between dysplasia and neoplasia a lesion size of 0.5 mm is chosen. Solcia E, Bordi C, Creutzfeldt W et al. Histopathological classification of nonantral gastric endocrine growth in man. Digestion. 1988;41:185–200. The aim of this classification is to type duodenal malrotation according to the anatomical site of the malrotation. Type A Normal duodenum B Malrotation of the duodenal bulb C Malrotation of the superior part of the duodenum D Malrotation of the superior duodenal flexure E Malrotation of the descending part of the duodenum F Malrotation of the inferior duodenal flexure G Malrotation of the transverse part of the duodenum H Malrotation of the ascending part of the duodenum I Malrotation of the transverse and ascending parts of the duodenum Fig. 2.51 Malrotation of the duodenum: classification according to Gravgaard. From Gravgaard E, Holm Möller S, Andersen D. Malrotation of the duodenum. Frequency in a radiographic control group. Scan J Gastroent. 1977;12:585–588. By permission of Taylor & Francis AS. The classification shows various patterns of duodenal malrotation causing luminal narrowing. Gravgaard E, Holm Möller S, Andersen D. Malrotation of the duodenum. Frequency in a radiographic control group. Scan J Gastroent. 1977;12:585–588. 1 Nonrotation: with a right-sided small intestine and left-sided colon 2 Reverse rotation: when a clockwise 90° rotation leaves the small bowel superficial to the transverse colon, which often passes through the small intestinal mesentery 3 Malrotation: failure to complete the normal rotatory process Fig. 2.52 Small intestine: classification of rotatory anomalies according to Bouchier: nonrotation type 1. Different types of nonfixation and nonrotation: (a) nonrotation; (b) nonrotation of right colon. Both situations allow volvulus. Bouchier IAD, Allan RN, Hodgson HJS, Keighley MRB, eds. In: Gastroenterology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. London: WB Saunders Company; 1993:360. Type Ia Nonrotation of the colon and duodenum: the duodenum and jejunum remain to the right of the spine and the colon to the left. Type IIa Nonrotation of the duodenum only Type IIb The duodenum and colon show reversed rotation Type IIc Only reversed rotation of the duodenum. The duodenum passes anterior to the SMA and the large bowel passes in front of both of them Type IIIa Both the duodenum and colon are not rotated Type IIIb Incomplete fixation of the hepatic flexure Type IIIc Incomplete attachment of the cecum Type IIId Internal hernia near the ligament of Treitz Several types of malrotation are classified according to the embryologic state of development. Type Ia (nonrotation) is estimated to be an incidental finding in 0.2% of adults. Stinger DA. Pediatric Gastrointestinal Imaging. Philadelphia: BC Decker; 1989: 235–239. Nonrotation Early arrest of rotation of the duodenojejunal loop leaving it in the right side of the abdomen Incomplete rotation Arrest of the duodenojejunal loop after it has partially rotated around the superior mesenteric artery but has not ascended to a normal position From Rescorla FJ, Grosfeld JL. Anomalies of rotation and fixation. Surgery. 1990;108:710–715. With permission of Elsevier. Rescorla FJ, Grosfeld JL. Anomalies of rotation and fixation. Surgery. 1990;108:710–715. Stage I Omphaloceles caused by failure of the gut to return to the abdomen Stage II Nonrotation, malrotation, and reversed rotation Stage III Unattached duodenum, mobile cecum, and an unattached small bowel mesentery From Gohl ML, DeMeester TR. Midgut nonrotation in adults. Am J Surg. 1975;129:319–323. With permission from Excerpta Medica Inc. Intestinal anomalies are categorized by the stage of their occurrence. Gohl ML, DeMeester TR. Midgut nonrotation in adults. Am J Surg. 1975;129:319–323. Type I Atresia with a complete occlusion of the intestinal lumen by a diaphragm Type II Atresia with complete occlusion of the intestinal lumen terminating into a blind end and joined by a cord-like structure Type III Atresia with complete occlusion as in Type II but without any connection between the proximal and distal segments and, in addition, a V-shaped defect in the mesentery From Bland-Sutton JD. Imperforate ileum. Am J Med Sci. 1889;98:457–462. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). Intestinal atresia is typically classified using the 1889 descriptions by Bland-Sutton and the 1964 descriptions by Louw. Bland-Sutton JD. Imperforate ileum. Am J Med Sci. 1889;98: 457–462. Type I Intra-luminal diaphragm with seromuscular continuity Type II Cord-like segment between the bowel blind ends Type IIIa Atresia with complete separation of blind ends and V-shaped mesenteric defect Type IIIb Jejunal atresia with extensive mesenteric defect and distal ileum acquiring its blood supply entirely from a single ileocolic artery. The distal bowel coils itself around the vessel, giving the appearance of an apple peel deformity Type IV Multiple atresias of the small intestine Fig. 2.53 Intestinal atresia: classification according to Louw. From Louw JH, Barnard CN. Congenital intestinal atresia. Observation on its origin The Lancet. 1955;2:1065–1067. With permission of Elsevier. Type IIIa is most commonly found. Grosfeld JL, Ballantine TV, Shoemaker R. Operative management of intestinal atresia and stenosis based on pathologic findings. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:368–375. Louw JH, Barnard CN. Congenital intestinal atresia. Observation on its origin. Lancet. 1955;2:1065–1067. Louw JH. Investigations into the etiology of congenital atresia of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1964;7:471–478. (a) Septal (b) Fibrous cord (c) Gap with defect in the mesentery (d) Multiple atresias (e) Apple peel intestine syndrome Fig. 2.54 Mid-gut atresia: types of intestinal atresia. From De Lorimier AA, Fonkalsrud EW, Hays DM. Congenital atresia and stenosis of the jejunum and ileum. Surgery. 1969;65:819–827. With permission of Elsevier. Anatomic variants of intestinal atresia are described. Blyth H, Dickson JAS. Apple peel syndrome (congenital intestinal atresia). A family study of seven index patients. J Med Genet. 1969;6:275–277. De Lorimier AA, Fonkalsrud EW, Hays DM. Congenital atresia and stenosis of the jejunum and ileum. Surgery. 1969;65: 819–827. Type I Membranous obstruction Type II Interrupted bowel Type III Apple-peel deformity Type IV Multiple atresias From Martin LW, Zerella JT. Jejunoileal atresia: a proposed classification. J Pediatr Surg. 1976;11:399–403. With permission of Elsevier. Proposed classification based on a combination of morphology and clinical characteristics. Martin LW, Zerella JT. Jejunoileal atresia: a proposed classification. J Pediatr Surg. 1976;11:399–403. The aim was to develop a grading system for severity of duodenal injury. Grade Injury Description I Hematoma Involving single portion of the duodenum Laceration Partial thickness, no perforation II Hematoma Involving more than one portion Laceration Disruption < 50% of circumference III Laceration Disruption 50%–75% circumference of D2; disruption 50%–100% circumference of D1, D3, D4 IV Laceration Disruption > 75% circumference of D2; involving ampulla or distal common bile duct V Laceration Massive disruption of duodenopancreatic complex Vascular Devascularization of duodenum From Asensio JA, Feliciano DV, Britt LD, Kerstein MD. Management of duodenal injuries. Curr Probl Surg. 1993;30:1023–1093. With permission of Elsevier. The grading should advance one grade for multiple injuries to the same organ. Asensio JA, Feliciano DV, Britt LD, Kerstein MD. Management of duodenal injuries. Curr Probl Surg. 1993;30:1023–1093. To grade the endoscopic appearance of bulbo duodenal inflammation. Grade 0 Normal mucosa 1 Edematous mucosa 2 Hyperemia of the mucosa 3 Petechiae of the mucosa 4 Erosions of the mucosa From Joffe SN, Lee FD, Blumgart LH. Duodenitis. Clin Gastroenterol. 1978;7:635–650 (continued as Gastroenterology Clinics of North America). With permission of Elsevier Inc. Duodenitis is described as a clinical entity that can give rise to dyspepsia and, on rare occasions, gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Joffe SN, Lee FD, Blumgart LH. Duodenitis. Clin Gastroenterol. 1978;7:635–650. To examine operative risk factors for patients with perforated duodenal ulcers. Major medical illness Preoperative shock, systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg Longstanding perforation (more than 24 hours) From Boey J, Wong J, Ong GB. A prospective study of operative risk factors in perforated duodenal ulcers. Ann Surg. 1982;195:265–269. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). The scoring system can predict mortality after open and laparoscopic surgery for perforated peptic ulcers. Major medical illness includes severe cardiac disease, severe pulmonary disease, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, and hepatic precoma. The mortality rate increases progressively with increasing numbers of risk factors: 0, 10, 45.5, and 100% in patients with none, one, two, and all three risk factors, respectively. Boey J, Wong J, Ong GB. A prospective study of operative risk factors in perforated duodenal ulcers. Ann Surg. 1982;195: 265–269. Boey J, Choi SK, Poon A, Alagaratnam TT. Risk stratification in perforated duodenal ulcers. A prospective validation of predictive factors. Ann Surg. 1987;205:22–26. To grade the histologic severity of the mucosal injury in the proximal small bowel. Pre-infiltrative (type 0) Normal intestinal lesion Infiltrative (type 1) Normal mucosal architecture in which the villous epithelium is markedly infiltrated by intra-epithelial lymphocytes Hyperplastic (type 2) Similar to type 1, and crypt enlargement Destructive (type 3) Flat mucosa Grade IIIa Partial villous atrophy Grade IIIb Subtotal villous atrophy Grade IIIc Total villous atrophy Hypoplastic (type 4) Irreversible hypoplastic or atrophic Grade I Intra-epithelial lymphocytosis (> 30/100 enterocytes) Grade II Intra-epithelial lymphocytosis and crypt hyperplasia Grade IIIa Partial villous atrophy Grade IIIb Subtotal villous atrophy Grade IIIc Total villous atrophy Grade IV Irreversible hypoplastic/atrophic changes From Marsh MN. Gluten major histocompatibility complex and the small intestine: A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten-sensitivity (celiac sprue). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330–354. With permission of the American Gastroenterological Association. The Marsh grading system is increasingly used to quantify the morphologic alterations in coeliac disease. Marsh MN. Gluten major histocompatibility complex and the small intestine: A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten-sensitivity (celiac sprue). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330–354. Wahab PJ, Crusius BA, Meijer JWR, Mulder CJJ. Gluten challenge in borderline gluten-sensitive enteropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1464–1469. Fig. 2.55a–e Coeliac disease: grading according to Marsh. a Marsh I: Lymphocytic enteritis. b Marsh II: lymphocytic enteritis with crypt hyperplasia. c Marsh IIIA: partial villous atrophy. Fig. 2.55d, e d Marsh IIIB: subtotal villous atrophy. e Marsh IIIC: total villous atrophy. To modify the stages according to Marsh, so that they may be used for diagnostic purposes. Mild villous atrophy Minor or moderate degrees of shortening and blunting of the villi Marked villous atrophy Only short tent-like remainders of the villi are seen Flat mucosa/total villous atrophy No more villi are to be recognized and the surface is flat From Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1185–1194. With permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). Grading based on the number of intra-epithelial lymphocytes, crypt hypertrophia, and villous atrophy. Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1185–1194. The Working Group of the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition in 1990 revised the criteria for gluten enteropathy. Characteristic morphologic abnormality of small bowel mucosa while the patient is on a diet containing gluten While on a gluten-containing diet the presence of serum IgA antibodies to one or more of the following: – Gliadin (AGA) – Endomysium (IgA-EMA) – Tissue transglutaminase (IgA—tTG) Clinical remission within a few weeks of starting a gluten-free diet Disappearance of antibodies within a few weeks of starting a gluten-free diet From Walker-Smith JA, Schmitz J, Shmerling DH, Visakorpi JK. Revised criteria for diagnosis of coeliac disease: report of the Working Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:909. With permission of BMJ Publishing Group. The criteria include histopathologic alterations in duodenal biopsies, clinical response to gluten withdrawal, and presence of antiendomysial antibodies. Walker-Smith JA, Schmitz J, Shmerling DH, Visakorpi JK. Revised criteria for diagnosis of coeliac disease: report of the Working Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:909. Postoperative enterocutaneous fistulas are classified based on the origin of the fistula and the daily output. Type I Esophageal, gastric, and duodenal fistulae II Small bowel III Large bowel IV All the aforementioned drain through a large abdominal wall defect High output > 500 ml/day Low output < 500 ml/day From Schein M, Decker GA. Postoperative external alimentary tract fistulas. Am J Surg. 1991;161:435–438. With permission from Excerpta Medica Inc. This classification is based on the Sitges-Serra classification. Type IV has the highest mortality rate (60%), followed by type II (33%), type III (20%) and type I (17%). High output fistulas usually require surgical intervention. Schein M, Decker GA. Postoperative external alimentary tract fistulas. Am J Surg. 1991;161:435–438. Sitges-Serra A, Jaurrieta E, Sitges-Creus A. Management of postoperative enterocutaneous fistulas: The role of parenteral nutrition and surgery. Br J Surg. 1989;69:147–150. Fistulas are classified according to complexity, anatomic location, and physiology. Simple fistulas No organ involvement or associated abscess Type I complex Associated with an abscess or multiple organs Type II complex Enterostoma within the base of a disrupted wound Fig. 2.56a, b Enterocutaneous fistulae: classification according to Rolstad and Bryant. a Simple enterocutaneous fistula. b Complex type I fistula with associated abscess. Type I Esophageal, gastric, and duodenal Type II Small bowel Type III Large bowel Type IV From large abdominal wall defects greater than 20 cm2 Low volume < 200 ml/24 hours Moderate volume Between 200 and 500 ml/24 hours High volume > 500 ml/24 hours High volume fistulas are generally associated with high morbidity, high mortality, and less chance of spontaneous closure. Rolstad BS, Bryant R. Management of drain sites and fistulas. In: Bryant R, ed. Acute and Chronic Wounds. St. Louis: Mosby; 2000:317–341. To develop a classification system for duodenal polyps based on the number and size of polyps, histology, and degree of dysplasia. Stage Points 0 0 I 1–4 II 5–6 III 7–8 IV 9–12 From Spigelman AD, Williams CB, Talbot IC, Domizio P, Phillips RK. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1989;2:783–785. With permission of Elsevier. This is a commonly used grading of duodenal adenomatosis in FAP. Offerhaus GJ, Entius MM, Giardiello FM. Upper gastrointestinal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:667–669. Spigelman AD, Williams CB, Talbot IC, Domizio P, Phillips RK. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1989;2:783–785. TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed T0 No evidence of primary tumor Tis Carcinoma in situ T1 Tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa T2 Tumor invades muscularis propria T3 Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into the subserosa or into the nonperitonealized perimuscular tissue (mesentery or retroperitoneum) with extension 2 cm or less T4 Tumor perforates the visceral peritoneum or directly invades other organs or structures (includes other loops of small intestine, mesentery, or retroperitoneum more than 2 cm, and abdominal wall by way of serosa; for duodenum only, invasion of pancreas NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed N0 No regional lymph node metastasis N1 Regional lymph node metastasis MX Distant metastasis cannot be assessed M0 No distant metastasis M1 Distant metastases GX Grade cannot be assessed G1 Well differentiated G2 Moderately differentiated G3 Poorly differentiated G4 Undifferentiated RX Presence of residual tumor cannot be assessed R0 No residual tumor R1 Microscopic residual tumor R2 Macroscopic residual tumor From Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer, 2002. Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed (2002) published by Springer-New York, www.springeronline.com. The AJCC TNM staging system uses three basic descriptors that are then grouped into stage categories. The first component is “T,” which describes the extent of the primary tumor. The next component is “N,” which describes the absence or presence and extent of regional lymph node metastasis. The third component is “M,” which describes the absence or presence of distant metastasis. The final stage groupings (determined by the different permutations of “T,” “N,” and “M”) range from Stage 0 through Stage IV. Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer, 2002. http://www.cancerstaging.org/. To classify the histopathology of immunoproliferative small-intestinal disease. (a) Diffuse, dense, compact, and apparently benign lymphoproliferative mucosal infiltration: – (i) Pure plasmacytic – (ii) Mixed lymphoplasmacytic (b) As in (a), plus circumscribed “immunoblastic” sarcoma (s), in either the intestine and/or mesenteric lymph nodes (c) Diffuse “immunoblastic” or plasmocytic sarcoma with or without demonstrable, apparently benign lymphoplasmacytic infiltration (a) Atypical plasma cells or large lymphoid cells (immuno-blasts) may be scattered within the lymphoplasmacytic infiltration; (b) and (c) cells resembling Sternberg–Reed cells may be part of the tumor infiltrate. WHO. Alpha-chain disease and related small-intestinal lymphoma: a memorandum. WHO Bull. 1976;54:615–624. To propose a pathologic staging classification for biopsies taken during staging laparotomy. 0 Benign-appearing lymphoplasmacytic mucosal infiltrate (LPI), no evidence of malignancy I LPI and malignant lymphoma in either intestine (Ii) or mesenteric lymph nodes (In), but not both II LPI and malignant lymphoma in both intestine and mesenteric lymph nodes III Involvement of retroperitoneal and/or extra-abdominal lymph nodes IV Involvement of noncontiguous nonlymphatic tissues Unknown Inadequate staging Reproduced from Salem PA, Nassar VH, Shahid MJ et al. “Mediterranean abdominal lymphoma” or immunoproliferative small intestinal disease. Part I: clinical aspects. Cancer. 1977;40:2941–2947. With permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Staging laparotomy consists of gross examination of abdominal organs, resection of grossly involved segments of small intestine and multiple resections of uninvolved adjacent segments, splenectomy in the presence of alpha heavy-chain disease or lymphomatous changes on preoperative intestinal biopsies or frozen section, wedge and needle liver biopsies, lymph node resection from splenic pedicle, porta hepatis, mesentery and paraortic region, iliac crest bone marrow biopsy. Mesenteric lymph nodes may harbor malignant lymphoma even when mucosa reveals a benign-appearing infiltrate only. Stage 0 can be totally reversible when treated with antibiotics. Salem PA, Nassar VH, Shahid MJ et al. “Mediterranean abdominal lymphoma” or immunoproliferative small intestinal disease. Part I: clinical aspects. Cancer. 1977;40: 2941–2947. To achieve increased knowledge of alpha-chain disease and to create a practical staging system on which therapeutic schemes can be based. Stage A A mature plasmacytic or lymphocytoplastic infiltrate invades the mucosal lamina propria and is sometimes associated with a variable amount of villous atrophy B Intermediate. The infiltrate invades the submucosa C Immunoblastic lymphoma either forming discrete ulcerated tumors or extensively infiltrating long segments of the intestinal wall Reproduced from Galian A, Lecestre MJ, Scotto Y, Bognel C, Matuchansky C, Rambaud JC. Pathological study of alpha-chain disease with special emphasis on evolution. Cancer. 1977;39:2081–101. With permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Stage A is characterized by a diffuse, dense, and apparently benign plasmacytic infiltration of mucosa and/or lymph nodes, and Stage C by the presence of low or high grade lymphomas with or without benign lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. Stage B is intermediate between Stages A and C and is characterized by mixed mature and dystrophic plasma cells infiltrating the mucosa and villous atrophy. Complete and prolonged remission has been seen in stage A only, sometimes with oral antibiotics alone. Fermand JP, Brouet JC. Heavy-chain diseases. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:1281–1294. Galian A, Lecestre MJ, Scotto Y, Bognel C, Matuchansky C, Rambaud JC. Pathological study of alpha-chain disease with special emphasis on evolution. Cancer. 1977;39:2081–101. The Bristol stool form scale gives an estimation of stool water content through analysis of fecal appearance. 1 Separate, hard lumps—like nuts 2 Sausage-shaped and lumpy 3 Sausage-shaped, cracked surface 4 Sausage or ‘snaky’, smooth, soft 5 Soft blobs, clear cut edges 6 Fluffy pieces, ragged edges, ‘mushy’ 7 Watery, no solids Hard stools Score 1–3 Intermediate consistency Score 4 Loose stools Score 5–7 From O’Donnell LJD, Virjee J, Heaton KW. Detection of pseudo-diarrhea by simple clinical assessment of intestinal transit rate. BMJ. 1990;300:39–40. With permission of BMJ Publishing Group. Typing stool appearance appears reproducible and reflects the water content and intestinal transit time.