PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Rectal prolapse is most common in multiparous elderly women with long-standing constipation. A small percentage is also seen in young male patients. Scleroderma and psychiatric disorders are also more common in patients with rectal prolapse.

■ Patients describe having tissue extrude from their anus that usually retracts on its own or with manual pressure. Prolapse is most often associated with episodes of straining but it can occur even with ambulation, especially in elderly female patients. It is important to elicit how much they are prolapsing, how often, and how much it is bothering them in order to decide whether to operate. Prolapse is often associated with mild bleeding and mucus.

■ It is important to elicit any bowel habits dysfunction that has to be addressed. Recurrence rates of prolapse are higher after surgery when severe constipation or obstructed defecation due to pelvic floor dysfunction are not addressed.

■ The patient should be asked about their continence as the surgeries for prolapse described here do not immediately improve continence. After prolapse surgery, about half of patients have some improvement in continence over time, but if their incontinence is severe and they cannot squeeze on exam, they may be better served with an ostomy. Intense counseling is critical.

■ Associated gynecologic and/or urologic pelvic floor dysfunction issues (including difficulty with urination and uterine prolapse) commonly seen in rectal prolapse patients should be addressed in a multidisciplinary fashion together with a urogynecologist.

■ Patients often come with digital photographs of their prolapse that allow for confirmation of the diagnosis. Otherwise, it is important to elicit the prolapse in the clinic to be able to differentiate it from prolapsing hemorrhoids.

■ The best way to confirm the rectal prolapse is to give the patient 5 minutes on the toilet to elicit the prolapse and then examine them. Rectal prolapse looks like a single long tube sticking out with concentric ring; prolapsing hemorrhoids look like multiple individual quadrants of tissue (FIG 1).

■ Physical exam should include digital rectal exam to assess for masses. Having the patient push during the exam allows the examiner to feel for enterocele, rectocele, and cystocele. In addition, the patient should be asked to squeeze to assess the sphincter muscles.

■ Patients with an incarcerated rectal prolapse may on occasion present to the emergency room. In these cases, the treatment depends on the appearance of the bowel. If viable, gentle reduction with sedation, reassurance, and education are usually all that is needed and the patient can follow up electively; if not viable, a perineal proctectomy is needed.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Any patient being evaluated for rectal prolapse should have a colonoscopy to rule out either a malignancy acting as the lead point of the prolapse or a synchronous tumor.

■ In patients that are unable to elicit prolapse or bring you a picture, a defecography can be very helpful. During this procedure, the patient’s small bowel, rectum, and vagina are all filled with contrast and the patient is asked to have a barium bowel movement while the radiologist takes a video. This often demonstrates the prolapse along with other types of pelvic floor dysfunction. The prolapse may not be seen on defecography, as evacuation of barium requires less straining than evacuation of hard stool in constipated patients.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Operative Planning and Strategy

■ The choice of operation is dependent on many factors including patient health, prior surgeries, the operating surgeon’s comfort with laparoscopy, and whether the patient has a history of constipation.

■ If the patient is healthy enough, then an abdominal rather than a perineal approach should be offered due to the lower risk of recurrence. Otherwise, they may be better served with a lower risk perineal operation or no operation at all.

■ Rectal prolapse is not dangerous unless incarcerated, so not all patients are offered operation.

■ Abdominal surgery for rectal prolapse should include dissection posterior to the mesorectum with fixation of the mobilized rectum just below the sacral promontory, as this fixation decreases the risk of recurrence. The fixation can be performed with sutures or with mesh.

■ In constipated patients, resection of the sigmoid colon is recommended. In these cases, although not proven beneficial by Cochrane review of available evidence, either a full bowel preparation or just enemas can be performed preoperatively at the surgeon’s discretion.

■ The surgery can be performed open or laparoscopically. Laparoscopic surgery is associated with significant short-term advantages over open surgery.

■ Preoperative antibiotics are given within 1 hour of incision to decrease the risk of postoperative wound infection and are stopped within 24 hours of surgery.

■ Heparin prophylaxis is given perioperatively to lower the risk of deep vein thrombosis.

Positioning

■ Any rectal prolapse should be reduced manually prior to starting the operation.

■ For laparoscopic operations, the patient is placed on a lithotomy position with the legs on Yellofin stirrups and with the thighs parallel to the ground to avoid conflict with the surgeon’s arms (FIG 2). Avoid pressure on the calves and lateral peroneal nerves.

■ Both arms are tucked and padded to avoid nerve injuries (for open cases, the arms are placed on arm boards laterally). All lines and cords are kept out of the tucking.

■ Tape the patient across the chest over a towel to secure him/her to the operating room (OR) table.

TECHNIQUES

LAPAROSCOPIC SUTURE RECTOPEXY

Insufflation, Port, and Team Setup

■ The abdomen is accessed with either a Veress needle or a Hassan port at the inferior portion of the umbilicus and carbon dioxide (CO2) pneumoperitoneum is established.

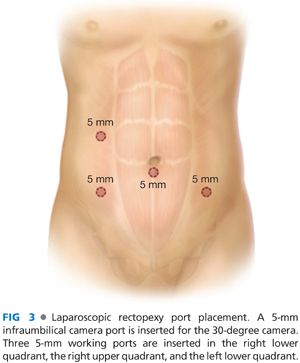

■ Port placement (FIG 3): A 5-mm infraumbilical camera port is inserted for the 30-degree camera. Three 5-mm working ports are inserted in the right lower quadrant, the right upper quadrant, and the left lower quadrant.

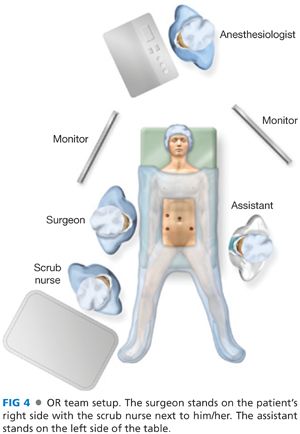

■ The surgeon stands on the patient’s right side, with the scrub nurse next to him/her. The assistant stands on the left side of the table (FIG 4).

Posterior Dissection

■ The patient is placed in a steep Trendelenburg position with the left side up. The bowel is placed in the upper abdomen. The sigmoid colon and rectum are often very redundant and can be hard to manipulate. At times, this may require additional port placement.

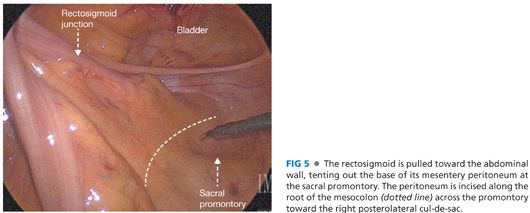

■ The rectosigmoid is pulled toward the abdominal wall, tenting upward the base of its mesentery at the sacral promontory (FIG 5). The peritoneum is incised along the root of the mesocolon with cautery across the promontory and toward the right and left posterolateral aspect of the cul-de-sac.

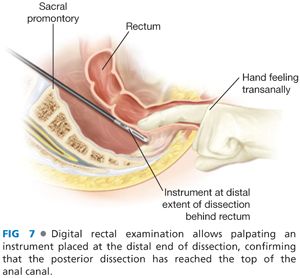

■ The rectum is then lifted anteriorly toward the abdominal wall in order to reveal the alveolar plane in the presacral space located between the mesorectum and the presacral fascia (FIG 6). Dissect the presacral space distally with an energy device until reaching just above the anal canal. Digital rectal examination may be needed to confirm the distal extent of dissection is appropriate (FIG 7).

■ Avoid penetration into the endopelvic fascia along the lateral pelvic wall, because this can lead to serious bleeding from the hypogastric vein and its branches. Also, dissecting into the presacral fascia could result in catastrophic bleeding from the presacral venous plexus.

■ The sympathetic nerves should be identified and preserved intact in the retroperitoneum.

■ Minimize unnecessary dissection of the lateral rectal stalks.

Rectopexy

■ Completely reduce the prolapse by retracting the rectosigmoid junction in a cephalad direction.

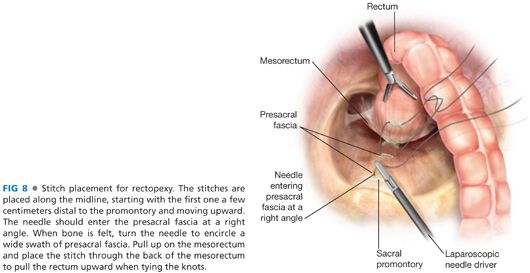

■ The rectopexy sutures (braided nonabsorbable or absorbable sutures) are placed starting just below the top of the promontory. While retracting the rectum anteriorly, three sutures are placed along the midline, from the presacral fascia to the back of the mesorectum, placing the most distal stitch first (FIG 8). SH needles will fit through 5-mm ports if the curve of the needle is slightly flattened.

■ When placing these stitches, it is important to have the needle enter at a right angle to the bone and then turn the needle after the bone is felt so that a wide swath of presacral fascia is incorporated in the stitch (FIG 8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree