Open Hartmann’s Reversal

Roberta L. Muldoon

Introduction

The majority of diseases of the colon can be managed with a single-stage procedure. There are, however, still circumstances in which the operating surgeon is concerned about performing a primary anastomosis after having completed a segmental resection of the left colon, and feels that stool diversion is in the best interest of the patient. Severe inflammation or gross contamination of the abdominal cavity may preclude primary anastomosis. The most common scenarios in which Hartmann’s procedures are performed are cancer and perforated diverticulitis with abdominal sepsis. A Hartmann’s procedure leaves the patient with an end colostomy as well as a rectal stump. Ideally, over time the inflammation or primary condition resolves, and Hartmann’s reversal or colostomy takedown can be considered. This procedure is known for its high morbidity, so caution should be exercised in preparing for this procedure.

A number of factors should be kept in mind when deciding to proceed with Hartmann’s reversal. These factors will impact the likelihood of a patient having a complication either during or after the procedure. By optimizing the condition of the patient, one may be able to decrease the morbidity associated with this procedure.

The timing of the reversal has been examined, but there is no clear consensus as to when it is appropriate to proceed. Aydin et al. studied 121 patients who underwent successful Hartmann’s reversal. They found that patients undergoing reversal at 4 months after the primary procedure were 2.5 times more likely to have a surgical complication when compared with those who had the reversal done within 4 months of the primary procedure. Those patients who underwent reversal at 8 months after the primary procedure were 5.5 times more likely to have a surgical complication when compared with patients who had reversal within the 4-month window (1). This finding suggests that closure within 4 months is the safest time to proceed. Pearce et al. reviewed 145 patients who underwent Hartmann’s reversal and found that 6 out of 12 patients (50%) who underwent reversal in under 3 months from the time of the primary surgery suffered an anastomotic leak. Twenty-eight

patients underwent reversal between 3 and 6 months after their initial surgery. Of these, seven patients (25%) suffered an anastomotic leak. Forty patients had their reversal after 6 months from the original surgery, and all healed well without evidence of leak (2). This paper suggests that a waiting period of 6 months is the safest for the patient. When Keck et al. reviewed their data of 111 Hartmann’s reversals, they found no difference in morbidity, mortality, or complication rates between those patients who had their takedown early (before 15 weeks) or late (after 15 weeks). They did find that patients whose reversals were done early did have longer hospitalizations, and that the operations were perceived by the surgeon as being more difficult (3). It is important to note that none of these papers specifically looked at the severity or complexity of the original operation. This status would clearly affect the recovery time of the patients and would clearly have an effect on the ease and success of the reversal procedure.

patients underwent reversal between 3 and 6 months after their initial surgery. Of these, seven patients (25%) suffered an anastomotic leak. Forty patients had their reversal after 6 months from the original surgery, and all healed well without evidence of leak (2). This paper suggests that a waiting period of 6 months is the safest for the patient. When Keck et al. reviewed their data of 111 Hartmann’s reversals, they found no difference in morbidity, mortality, or complication rates between those patients who had their takedown early (before 15 weeks) or late (after 15 weeks). They did find that patients whose reversals were done early did have longer hospitalizations, and that the operations were perceived by the surgeon as being more difficult (3). It is important to note that none of these papers specifically looked at the severity or complexity of the original operation. This status would clearly affect the recovery time of the patients and would clearly have an effect on the ease and success of the reversal procedure.

It is generally accepted that early reversal (<3 months) may lead to complications secondary to adhesions and residual inflammation still present from the inciting process and the original surgery. This can lead to more difficult, prolonged surgeries, with increased blood loss and prolonged hospitalization. On the other end of the spectrum, it is thought that waiting too long may lead to difficulty in mobilizing and anastomosing the rectal stump, which decreases in size over time due to lack of use. It is important when reviewing this literature to consider the effect of the original operation on the outcome. None of these papers specifically evaluated at the complexity or indication for the original operation. Perhaps the increase in complications that is sometimes seen with waiting may be a reflection of the difficulty of the original operation, the severity of the disease process, patient comorbidities, and a prolonged recovery time from a difficult original surgery, rather than a reflection of just the passage of time.

The decision as to the appropriate timing of the reversal needs to be made on an individual basis. First and foremost, the patient must be in overall good condition with recovery from the primary surgery and able to undergo a second operation. Consideration of the original disease process, the operative intervention itself, as well as how the recuperation progressed will be a helpful information in planning when to proceed with the reversal. Ideally, the patients should be at or close to their premorbid state with regard to ambulation, nutrition, and overall strength. If they needed to be placed on steroids for treatment of their disease process, these should be weaned if possible prior to colostomy takedown. The initial inciting event should have resolved, and enough time given to have resolution of the inflammatory process. Finally, there should be no sign of ongoing infection, which could lead to an increased risk of wound infection or intra-abdominal abscess formation.

Preoperative evaluation includes assessment of the remaining colon as well as the rectal stump. The colon should be endoscopically evaluated to exclude cancer or other possible pathology of the colon. The rectal stump should also be viewed. This exclude associated rectal pathology, as well as to give an indication as to the length of the rectal stump. Knowledge of the length can be helpful in determining where to look for the proximal end in a pelvis that may have a significant amount of scar tissue present. It is very helpful also to review the operative note of the primary surgery, especially if you did not perform the original operation. Knowing, for example, that the bowel was tacked to the anterior abdominal wall or that a stitch had been placed at the proximal end of the bowel can be a valuable information. It is also helpful to know where the proximal end of the bowel might be located, so that it is not injured either with entry into the abdominal cavity or while lysing pelvic adhesions.

Patients should undergo a full bowel preparation prior to the surgery. If inspissated mucus is found at the time of endoscopic evaluation of the rectum, then enemas per rectum can be given to clear this prior to the surgery. Lastly, the need for the use of ureteral stents should be considered. Although the use of stents does not eliminate the risk of ureteral injury, it has been shown to improve early detection, which is associated with decreased morbidity associated

with this complication (4). The decision to use stents is based, in part, on the severity of the disease at the original operation as well as the difficulty of the primary operation. The time interval between the two surgeries, the patient’s history of prior operations, and the patients’ body habits should also be considered when making this decision.

with this complication (4). The decision to use stents is based, in part, on the severity of the disease at the original operation as well as the difficulty of the primary operation. The time interval between the two surgeries, the patient’s history of prior operations, and the patients’ body habits should also be considered when making this decision.

Technique

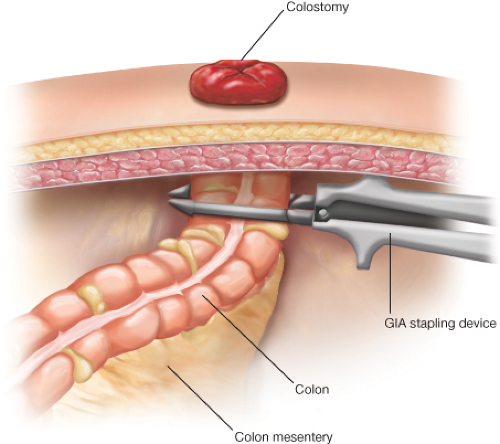

The patient should be positioned in the modified lithotomy position. Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis should be administered as well as a dose of preoperative antibiotics. A bladder catheter should be inserted and stents placed at this time if desired. The stoma can be sutured closed to minimize any contamination during the case. The stoma is then covered with sterile gauze to collect any fluid that might leak out from the stoma, and then the entire abdomen covered with an antimicrobial adhesive covering. After the abdomen is prepped and draped in the usual sterile manner, lower midline incision is made. Upon entering the abdomen, care should be taken to avoid injury of small-bowel loops that may be adherent to the anterior abdominal wall. All adhesions in and around the stoma should be carefully divided so that there is clear visualization of the distal colon exiting the anterior abdominal wall. Once the distal colon is circumferentially freed at the fascial level, the bowel can be divided. A GIA stapler is positioned just beneath the anterior abdominal wall with the intention of preserving as much of the bowel length as possible (Fig. 47.1). Once the colon is divided, it is usually easier to complete the remainder of the adhesiolysis. A retractor system can now be put into place. It is important to assess which vessels were divided at the primary operation and which vessels are still intact. This knowledge will be important, not only in assessing the remaining colon’s blood supply, but may also play a key role in the mobility of the colon reaching down to the proximal end of the rectum. The small bowel needs to be freed out of the pelvis and packed into the upper abdomen. The distal colon

can also usually be temporarily packed into the upper abdomen. It is the editor’s preference to first mobilize the stoma, and resect and close the proximal segment usually over a circular stapler anvil prior to reopening the laparotomy incision.

can also usually be temporarily packed into the upper abdomen. It is the editor’s preference to first mobilize the stoma, and resect and close the proximal segment usually over a circular stapler anvil prior to reopening the laparotomy incision.

Figure 47.1 Abdominal wall with colostomy in place. Stapler aligned just beneath abdominal wall ready to fire. |

With good visualization of the pelvis, the rectal stump can be identified and mobilized. If at the original surgery the rectal stump was long and sutured to the anterior or lateral wall, the localization is usually fairly straightforward. More often though, the case is that the rectal stump is shorter and has retracted into the pelvis with reperitonealization, making location more challenging. If it is difficult, the following maneuvers can be helpful. Air can be gently insufflated with a rigid proctoscope to help identify the rectum. The rectal sizers can also be used to stent the rectum, thus giving some direction as to its location and boundaries. The rigid proctoscope can also be inserted and advanced under direct visualization to help identify the most proximal end. The amount of mobilization necessarily depends on the length of the rectum, the type of anastomosis planned (stapled vs. hand-sewn), and the angulation of the rectum. If the rectum is straight, only the most proximal end needs to be mobilized ensuring that the edges are cleared for a “clean” anastomosis. If, however, the rectum has folded back on itself or has significant angulation present and you are planning a stapled anastomosis, then further mobilization will be necessary for safe insertion of the stapler from below. It is imperative that the rectum be adequately dissected free from bladder in the male and from the vagina in the female. It is sometimes difficult to assess the exact plane between the rectum and the vagina. In this case, it is often helpful to place either a finger or the rectal sizers in the vagina. The vagina can then be retracted anteriorly, which can assist in developing the plane between these two structures.

Once the rectum has been mobilized it must be assessed for suitability for anastomosis. The original etiology needs to be contemplated, and adequacy of the primary resection assessed. At times, in the setting of acute perforated diverticulitis, the perforated and most diseased portion of the colon is resected leaving behind a portion of the sigmoid colon down in the pelvis. In this setting, the distal portion of sigmoid needs to be resected, so the anastomosis is performed to the top of the true rectum. Likewise, if the pathology had revealed cancer with inadequate margins, addition resection might be merited. Once the rectum is assessed and ready for anastomosis, the distal colon needs to be assessed and prepared for anastomosis. The proximal colon must be anastomosed to the rectum and not to the distal sigmoid colon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree