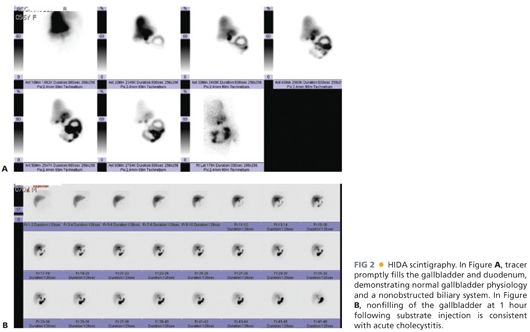

■ The other common imaging study used to diagnose gallbladder pathology is a nuclear medicine test called either hepatobiliary scintigraphy or a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan (commonly referred to as a HIDA scan.) In this test, a radiolabeled substrate is intravenously administered, taken up by the liver, and excreted into the biliary tree (FIG 2). If the substrate fails to fill the gallbladder within 1 hour, the sensitivity is 96% for acute cholecystitis.1 A HIDA scan will also provide information about obstruction of the common bile duct, as substrate will be seen accumulating in the duodenum if the duct is not obstructed. In the setting of hepatic failure or cholestasis, this study is not useful, as the liver often will not take up enough substrate to allow an adequate study. Gallstones are not revealed with this study, but rather, the presence or absence of cholecystitis is determined by assessing patency of the cystic duct regardless of the etiology. HIDA scintigraphy is generally performed if the clinical findings and ultrasound are inconclusive for calculous cholecystitis or in critically ill patients with suspected acalculous cholecystitis.2

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ The vast majority of patients will be appropriate candidates for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Conversion from laparoscopy due to variable anatomy or severe inflammation is the most common indication for the open procedure. Rare patients in whom a primary open cholecystectomy should be considered are the following:

■ Septic patients on vasoactive agents for hemodynamic support that have failed percutaneous drainage

■ Patients with complicated anterior abdominal walls and/or severe adhesions. Specifically, if there are large pieces of prosthetic mesh in the umbilical and epigastric areas and/or prior RUQ surgery, laparoscopic completion of a cholecystectomy can be challenging.

■ The need for concomitant open common bile duct exploration

Positioning

■ The patient is positioned supine. Arms can be tucked by the side or extended out at right angles to the bed. An oral or nasal tube for gastric decompression is placed.

TECHNIQUES

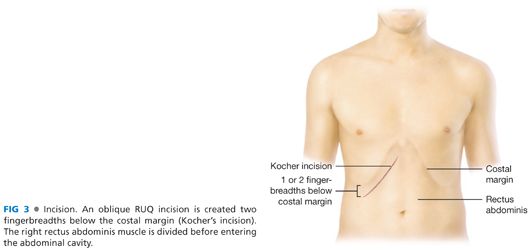

INCISION

■ The gallbladder is most easily accessed through an oblique RUQ incision (FIG 3). The incision should be placed two fingerbreadths below the right costal margin to facilitate fascial closure. In patients with significant hepatomegaly, the incision may be moved inferiorly to two fingerbreadths below the palpable liver edge, but this should rarely be necessary. The incision is carried down to the fascia.

OPENING OF THE ABDOMINAL WALL

■ The anterior rectus fascia should be incised with electrocautery. A Kelly or other large clamp is placed under the lateral border of the rectus muscle, retracting it anteriorly, to facilitate division of the muscle with electrocautery. The superior epigastric vessels can be encountered, typically about halfway across the rectus. The vessels can be ligated or cauterized, or they can be reflected medially and preserved with the medial half of the rectus.

PLACEMENT OF RETRACTORS

■ This step is the key to a successful operation. Safely keeping the bowel out of the operative field and delivering the gallbladder to the center of the wound will make the remainder of the case straightforward with proper exposure. A Bookwalter fixed retractor or other table-mounted retractor should be used (FIG 4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree