Open Abdominoperineal Resection

David A. Rothenberger

Genevieve B. Melton Meaux

Abdominoperineal resection (APR) is generally performed for patients who have a rectal adenocarcinoma but may also be performed for benign conditions such as inflammatory bowel diseases or incontinence and is sometimes appropriate for other low anorectal and pelvic malignancies or as a salvage procedure for anal canal cancers. The technique discussed in this chapter is intended to achieve radical clearance of anorectal malignancies; more conservative techniques of APR used for benign conditions are not discussed here in detail. Both open laparotomy and minimally invasive laparoscopic approaches are used for APR of rectal cancer. Some surgeons now use a hybrid laparoscopic approach to explore the abdomen, mobilize the left colon, and then convert to an open or hand-assisted procedure via a lower midline incision to complete the abdominal phase. A prospective trial is now being done by the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group to determine if laparoscopic technique for rectal cancer resection is a safe and effective alternative to the open technique. Other similar trials are underway in other countries. This chapter focuses on the operative technique used during an open approach for APR. The principles and techniques described here are applicable with minor modifications to extended operations for rectal cancer including en bloc sacrectomy, vaginectomy, or pelvic exenteration.

The decision to do an anterior resection (AR) and anastomosis versus an APR and permanent colostomy is dependent on oncologic considerations, technical considerations, the surgeon’s skills and experience, anticipated functional outcomes, and patients’ desires. Important oncologic and technical considerations include preoperative level of the lesion and in particular its relationship to the anal sphincters and levators, pretreatment stage of the cancer including any local organ invasion or distant spread, histology predictors of poor outcome, and threatened or involved margins and the tumor response to neoadjuvant therapy. In general, obesity and the narrow male pelvis add to the technical challenges encountered by the rectal cancer surgeon. Both open APR and open AR curative-intent radical resections for rectal cancer use the same total mesorectal excision (TME) technique to mobilize the rectum with its mesorectum and achieve proximal, lateral, and radial margin clearance. The choice of APR versus AR is primarily dependent on the surgeon’s ability to achieve distal mural clearance of 2 cm and distal mesorectal

clearance of 5 cm and to perform a reliable sphincter-sparing anastomosis that will preserve good anorectal function. In general, the more distal the anastomosis is located, the higher the risk of anastomotic complications and the less good the function. Pelvic irradiation generally increases the risk of anastomotic problems and worsens the functional outcome. While patients understandably may prefer a sphincter-sparing proctectomy to APR, they should be informed that sphincter preservation is not uniformly associated with better quality of life (1). It is generally counterproductive to compromise control of the cancer in a heroic attempt to avoid a permanent colostomy as recurrences often result and/or functional results are so poor that quality of life is unacceptable. The ultimate decision making with respect to selecting AR or APR may not be possible until intraoperative assessment and mobilization of the rectum is complete.

clearance of 5 cm and to perform a reliable sphincter-sparing anastomosis that will preserve good anorectal function. In general, the more distal the anastomosis is located, the higher the risk of anastomotic complications and the less good the function. Pelvic irradiation generally increases the risk of anastomotic problems and worsens the functional outcome. While patients understandably may prefer a sphincter-sparing proctectomy to APR, they should be informed that sphincter preservation is not uniformly associated with better quality of life (1). It is generally counterproductive to compromise control of the cancer in a heroic attempt to avoid a permanent colostomy as recurrences often result and/or functional results are so poor that quality of life is unacceptable. The ultimate decision making with respect to selecting AR or APR may not be possible until intraoperative assessment and mobilization of the rectum is complete.

Assessment and Staging

All patients with a newly diagnosed rectal cancer should undergo full clinical assessment, pretreatment staging of the primary cancer, as well as a search for metastases and synchronous colonic abnormalities. A full discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this chapter. A history of pain with defecation may be indicative of involvement of the anal sphincters, whereas tenesmus may suggest a large or possibly fixed tumor. It is important to assess preoperative bowel function, including the presence of bowel incontinence as well as baseline sexual and urinary function. For distal rectal cancers, digital rectal examination can define tumor size, location from the anal verge, relationship to the anorectal ring, orientation within the anal canal (anterior, posterior, left, or right), and relative fixation (fixed, tethered, or mobile). Confirmation of these characteristics and biopsy for histologic confirmation of the diagnosis of rectal adenocarcinoma may be achieved by either flexible sigmoidoscopy or rigid proctoscopy. The latter is preferred by some surgeons as the most accurate method to assess precise distance and location of the lesion from the anal verge or dentate line. Complete colonoscopy is essential to exclude synchronous lesions or other colonic diseases. Pulmonary metastases are identified by chest x-ray or CT scan while hepatic metastases may be identified by abdominal CT scan. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) may be useful as a baseline.

Primary tumor staging has become increasingly important to determine whether neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy is indicated. While CT scanning is the mainstay for initial assessment of distant disease and is useful to assess gross pelvic abnormalities such as direct extension to adjacent organs, it is not adequate for primary rectal tumor staging. Endorectal ultrasonography (ERUS) appears most useful to stage early lesions and is a reliable method to assess tumor depth within the rectal wall (T1 and T2) and moderately accurate at assessing enlarged mesorectal lymph nodes (N-stage). For more extensive tumors, pelvic phased array magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered using a protocol specific for staging rectal cancer. Pelvic MRI appears to have several advantages over ERUS: (a) It is less operator dependent; (b) it provides a larger field of view beyond a few centimeters of the primary including the pelvic sidewall and other adjacent structures; (c) it is probably more accurate in assessing lymph node involvement; and (d) it provides anatomically relevant information to the surgeon. Not surprisingly, pelvic MRI has become increasingly utilized to stage rectal cancer (2). ERUS and pelvic MRI specific for rectal cancer staging may not be widely available or of adequate quality throughout the United States, so some patients may need to be referred to experienced centers to obtain these tests.

In the United States, most advanced mid or low rectal cancers with evidence of lymph node involvement and/or transmural spread of the primary are treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed 8–10 weeks later by radical surgical resection. Tattooing the distal edge of the tumor is sometimes useful to guide the subsequent resection and selection of a distal margin should a complete clinical response to the neoadjuvant therapy occur. The rationale for such neoadjuvant therapy is to decrease

the risk of local recurrence and thus improve survival. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is generally used as well to decrease the risk of distant metastases. In many parts of the world, the American approach is criticized for overtreating many patients. Many other protocols call for use of a less morbid, short-course neoadjuvant radiotherapy followed by radical surgery or for radical surgery alone if preoperative MRI suggests that TME can clear the rectal cancer adequately (3).

the risk of local recurrence and thus improve survival. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is generally used as well to decrease the risk of distant metastases. In many parts of the world, the American approach is criticized for overtreating many patients. Many other protocols call for use of a less morbid, short-course neoadjuvant radiotherapy followed by radical surgery or for radical surgery alone if preoperative MRI suggests that TME can clear the rectal cancer adequately (3).

Role of Multidisciplinary Team

While the colorectal surgeon usually has the primary responsibility to assess and direct the treatment of a patient with rectal cancer, appropriate decision making to optimize outcomes is enhanced by a multidisciplinary team of professionals similarly focused on rectal cancer care. Preoperative consultation with other specialty colleagues to plan the optimal treatment, achieve the optimal oncologic outcome with the least morbidity, and to implement a coordinated and safe operation is essential. For many advanced stage rectal cancers, medical and radiation oncologists will oversee a course of neoadjuvant chemoradiation. If there is involvement of the genitourinary tract or sacrum, preoperative consultation with a urologist, neurosurgeon, or orthopedic surgeon is advised. Patients with distal or mid rectal cancer should be seen preoperatively by an enterostomal therapist for counseling and marking of the abdominal wall for any potential stomas. In cases where it is not clear whether the procedure will be an APR versus AR and low anastomosis with a diverting ileostomy, both sides of the abdomen should be marked. Perineal wound closure may require plastic surgical consultation to plan a rotational myocutaneous flap.

Special Surgical Considerations

Pelvic Floor Anatomy

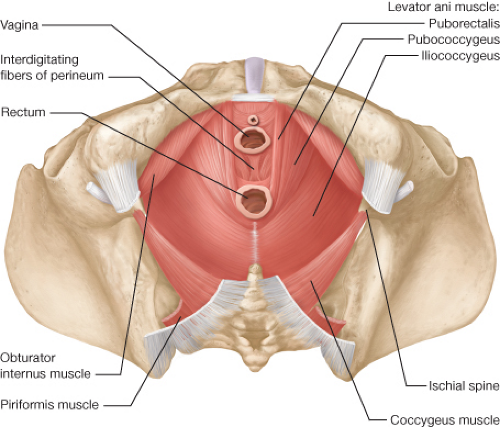

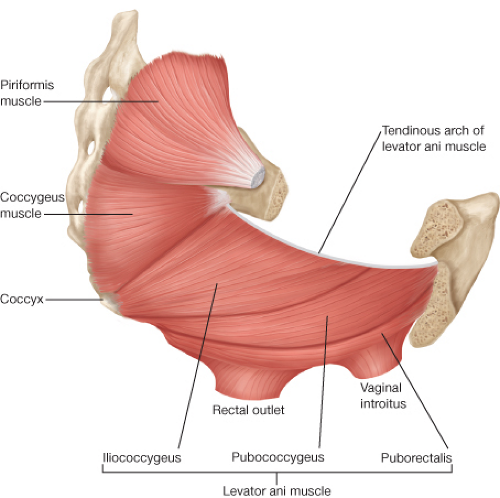

APR requires that the surgeon be intimately familiar with the anatomy of the pelvis and in particular, the pelvic floor and perineum (Figs. 31.1 and 31.2). The perineum is the

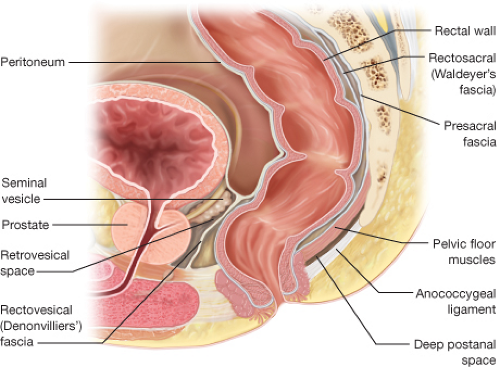

area between the thighs extending from the pubis to the coccyx. Its upper boundary is the lower surface of the levator ani. It is typically divided into an anterior urogenital region and a posterior anal region. The pelvic floor is a funnel-shaped, bilateral muscular plate that includes the three muscles of the levator ani (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus muscles) as well as the coccygeus muscle. The levator ani muscles are attached anteriorly to the pubis just lateral to the symphysis and posteriorly to the ischial spine. The puborectalis is a muscular loop without attachments to the coccyx with anterior fibers merging into the external sphincter. The pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus muscles arise from the arcus tendineus that extends from the pubis to the ischial spine. They insert on the ventral and lateral surfaces of the coccyx as well as to the anococcygeal raphe. The coccygeus muscle arises from the ischial spine and inserts into the lateral surface of the caudal part of the sacrum and the coccyx (Fig. 31.2). The pelvic floor muscles are covered by a parietal endopelvic fascial layer on their pelvic surface. The presacral Waldeyer’s fascia is a thickened part of the parietal fascia that covers presacral vessels and nerves and is attached to S3 and S4 sacral segments. Anteriorly, Denonvillier’s fascia separates the rectum from the seminal vesicles and prostate (Fig. 31.3).

area between the thighs extending from the pubis to the coccyx. Its upper boundary is the lower surface of the levator ani. It is typically divided into an anterior urogenital region and a posterior anal region. The pelvic floor is a funnel-shaped, bilateral muscular plate that includes the three muscles of the levator ani (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus muscles) as well as the coccygeus muscle. The levator ani muscles are attached anteriorly to the pubis just lateral to the symphysis and posteriorly to the ischial spine. The puborectalis is a muscular loop without attachments to the coccyx with anterior fibers merging into the external sphincter. The pubococcygeus and iliococcygeus muscles arise from the arcus tendineus that extends from the pubis to the ischial spine. They insert on the ventral and lateral surfaces of the coccyx as well as to the anococcygeal raphe. The coccygeus muscle arises from the ischial spine and inserts into the lateral surface of the caudal part of the sacrum and the coccyx (Fig. 31.2). The pelvic floor muscles are covered by a parietal endopelvic fascial layer on their pelvic surface. The presacral Waldeyer’s fascia is a thickened part of the parietal fascia that covers presacral vessels and nerves and is attached to S3 and S4 sacral segments. Anteriorly, Denonvillier’s fascia separates the rectum from the seminal vesicles and prostate (Fig. 31.3).

Recent Oncologic Insight—the “Waist”

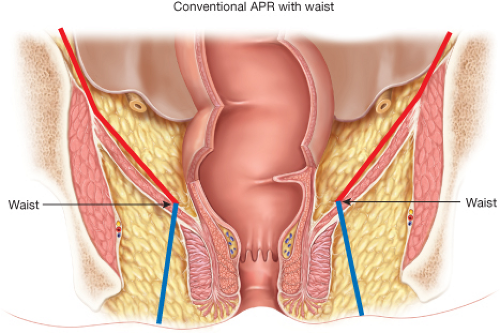

Curative intent APR is associated with higher rates of perforation, positive margins, and local recurrence than observed after AR. These poor outcomes seem independent of tumor stage or size (4). Some authors have suggested that distal rectal cancers have a different biology and routes of spread compared to proximal lesions. For instance, 25% of transmural cancers in the distal half of the rectum have lateral pelvic lymph node metastases located well beyond the dissection plane followed by TME (5). While this may explain some of the poor outcomes observed after APR, there is increasing concern that the poor results may be due in large part to anatomic and technical considerations not previously considered. Specifically, it has been suggested that the poor outcomes after APR are due to the close proximity of the cancer to the circumferential resection margin at the level of the anorectum distal to the levator muscle sling (6). As opposed

to a more proximal rectal cancer that is surrounded by the mesorectum enveloped within the endopelvic fascial plane, cancer in the distal anorectum has no comparable tissue surrounding it (Fig. 31.4). Nagtegaal et al. (4) assessed cancers <5 cm from the anal verge and found that there was little or no levator and sphincter muscles surrounding the specimen at the level of the cancer. This area has now been termed the “waist” in an APR specimen. Salerno et al. (6) found that the location of the “waist” was between 35 and 42 mm proximal to the anal verge, a site that correlates with the puborectalis.

to a more proximal rectal cancer that is surrounded by the mesorectum enveloped within the endopelvic fascial plane, cancer in the distal anorectum has no comparable tissue surrounding it (Fig. 31.4). Nagtegaal et al. (4) assessed cancers <5 cm from the anal verge and found that there was little or no levator and sphincter muscles surrounding the specimen at the level of the cancer. This area has now been termed the “waist” in an APR specimen. Salerno et al. (6) found that the location of the “waist” was between 35 and 42 mm proximal to the anal verge, a site that correlates with the puborectalis.

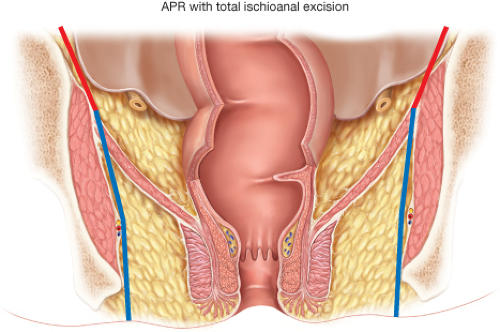

It is possible that a well-intentioned surgeon focused on performing a low anastomosis after TME for a distal rectal cancer may follow the mesorectum distally to the point where it thins and blends with the intersphincteric plane leaving almost no surrounding tissues on the cancer-bearing anorectum where it is excised, that is, at the “waist.” This is thought to result in high local recurrence rates. We agree with others that it is reasonable to modify the technique for radical APR to eliminate the “waist” and hopefully improve the poor results currently observed. The modifications described

in detail include: (a) stopping the abdominal dissection at the proximal level of the levator muscles and then (b) performing a more radical perineal excision of the levators including the puborectalis in the prone jackknife position. Thus, instead of following the levators distally and inward to the anorectal ring, the surgeon can purposefully dissect through the levators laterally along the side wall and include the soft tissue around the proximal aspect of the anorectal ring as part of the intact APR specimen. When done properly, the specimen will appear as a “cylinder” rather than as an APR with a distal “waist.” Holm terms this modified technique of APR for distal rectal cancers as a “total ischioanal excision” (Fig. 31.5) (7). Like Holm, we also believe that this modified technique is greatly facilitated by undertaking the perineal dissection with the patient in the prone jackknife position.

in detail include: (a) stopping the abdominal dissection at the proximal level of the levator muscles and then (b) performing a more radical perineal excision of the levators including the puborectalis in the prone jackknife position. Thus, instead of following the levators distally and inward to the anorectal ring, the surgeon can purposefully dissect through the levators laterally along the side wall and include the soft tissue around the proximal aspect of the anorectal ring as part of the intact APR specimen. When done properly, the specimen will appear as a “cylinder” rather than as an APR with a distal “waist.” Holm terms this modified technique of APR for distal rectal cancers as a “total ischioanal excision” (Fig. 31.5) (7). Like Holm, we also believe that this modified technique is greatly facilitated by undertaking the perineal dissection with the patient in the prone jackknife position.