Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-associated intestinal damage to the small and/or large bowel is frequent and may be present in up to 60% to 70% of patients taking these drugs long term. Intestinal damage is subclinical in most cases (eg, increased mucosal permeability, inflammation, erosions, ulceration), but more serious clinical outcomes, such as anemia and overall bleeding, perforation, obstruction, diverticulitis, and deaths, have also been described. Recent data suggest that serious lower gastrointestinal (GI) clinical events linked to NSAID use may be as frequent and severe as upper GI complications. Treatment and prevention strategies of NSAID-induced damage to the lower GI tract have not been defined so far. Misoprostol, antibiotics, and sulphasalazine have been proven to be effective in animal models, but they have not been properly tested in humans. Preliminary studies with COX-2 selective inhibitors in healthy volunteers have shown that these drugs are associated with less small bowel damage than traditional NSAIDs plus proton pump initiator, although their longterm effects in patients need to be tested. Post hoc analysis of previous outcome studies with these agents have shown contradictory results in the lower GI tract so far.

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) side effects are the most common adverse events of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, other GI side effects are increasingly being recognized in clinical practice. In the last few years, it is becoming clear that NSAIDs can damage the small bowel and the colon and that the magnitude of the damage may be greater than that of NSAID-associated gastropathy. In spite of this, awareness of NSAID-induced enteropathy is low in clinical practice. There are several reasons for the low appreciation of NSAID enteropathy. The condition is usually asymptomatic and diagnosis has, until recently, been possible only with the use of tests that are not available in clinical practice. Although case reports, epidemiologic studies, and pathologic series are available for more than 20 years, the current increasing interest in this field may be due to a growing investment on research from pharmaceutical companies with interest in NSAID gastropathy. Now that the safety concern for cardiovascular events seems to settle and this concern is almost similar for traditional NSAIDS (tNSAIDs) and coxibs, the interest is coming back to the GI tract, and the new territory to explore is the lower GI tract.

Mechanisms of intestinal damage by Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

It is not completely clear how NSAIDs initiate damage in the lower GI tract. The widespread view is that upper GI toxicity by NSAIDs is mediated by both a non–prostaglandin-dependent local injury and, overall, by the systemic inhibition of the cyclooxygenase (COX) -1 enzyme. This leads to a subsequent reduction in cytoprotective prostaglandins required for an effective mucosal defense. The pathogenic mechanism leading to inflammatory changes in the distal GI tract is less well known at this time. Although mucosal prostaglandin inhibition after NSAID use is present in all parts of the digestive tract, there are significant differences between the distal and the proximal GI tract in the concurrence of other pathogenic factors that may increase the damage. One proposed mode of action is that drug induces changes in local eicosanoid metabolism coupled with a topical toxic effect of the drug, increased by the enterohepatic circulation of the drug. These effects compromise the mucosal cell integrity, which translates to increased epithelial permeability. Increased intestinal permeability permits mucosal exposure to toxins and luminal aggressors such as bacteria and their degradation products, bile acids, and pancreatic secretion with a predictable inflammatory reaction. This inflammation varies in intensity from mild to severe, producing erosions and ulcers.

The importance of neutrophils in this process has been emphasized by the finding that NSAID-intestinal damage is almost completely abolished or markedly attenuated in neutropenic rats. As in other body tissues, the neutrophil recruitment in the intestine is a process mainly mediated by β2 integrins CD11/CD18 on stimulation of several cytokines. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) acts as a relevant cytokine promoting NSAID-induced neutrophil recruitment in the mucosa. Intestinal bacteria appear to be the main neutrophil chemoattractant. In this connection, a recent study found an unbalanced growth of gram-negative bacteria in the ileum of NSAID-treated animals and showed that heat-killed Escherichia coli cells, and their purified lipopolysaccharide caused deterioration of NSAID-induced ulcers. Indeed, lipopolysaccharide, a major cell wall component of gram-negative enterobacteria, was found capable of aggravating NSAID-induced intestinal injury.

Antimicrobials, such as tetracycline, kanamycin, metronidazole, or neomycin plus bacitracin, attenuate NSAID enteropathy, thus giving further support to the pathogenic role of enteric bacteria. An additional, although indirect, proof of the role exerted by gut bacteria in the pathogenesis of NSAID enteropathy is represented by the similarities between indomethacin-induced intestinal damage and Crohn’s disease. Not only are these lesions anatomically (both macro- and microscopically) similar but they are also sensitive to the same drugs, for example, sulfasalazine, steroids, immunosuppressive compounds, and antibiotics.

A recent study by Watanabe and colleagues extended these findings by adding another important piece to the puzzle. In particular, they showed experimentally that only a decrease in gram-negative but not gram-positive organisms lessens indomethacin-induced intestinal damage. These data have suggested a pathogenic mechanism of NSAID-induced enteropathy. Once the mucosal barrier has been disrupted by NSAIDs, luminal gram-negative bacteria enter the cell and are then recognized by the transmembrane toll-like receptor (TLR4) thanks to their lipopolysaccharides component. Activation of TLR4 induces cytokine mucosal expression, which triggers neutrophil recruitment with subsequent release of proteases and reactive oxygen species, leading ultimately to mucosal injury. The bacteria-induced inflammatory cascade could, therefore, be blunted either via manipulation of microbial ecology or through blockade of TLR4.

Enterohepatic recirculation of NSAIDs may be an important factor. NSAID-induced damage to the intestinal epithelium is therefore derived from a direct or local effect after oral administration, a recurrent local effect due to the enterohepatic recirculation of the drug, and the systemic effects after absorption. Supportive of this hypothesis is the fact that ligation of the bile duct prevents/reduces small intestinal damage by NSAIDs.

The degree of increase in permeability is related to the potency of inhibition of COX activity and is diminished by the administration of prostaglandins COX-2 selective inhibitors. There also are data suggesting that inhibition of both COX-1 and COX-2 is required as well as possible interference with mitochondrial energy metabolism of intestinal cells. Taken together, these data are consistent with the notion that the effect of intestinal permeability is primarily a local intestinal event and that COX-1 and/or dual COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition plays a role in this initial event. Once intestinal permeability is increased, a cascade of events, driven by toxin and bacteria, induce inflammation and mucosal ulceration, which could eventually progress to bleeding, perforation, or gut stricture due to fibrosis involved in the healing repair process. Why some lesions in some patients progress to more severe side effects and some others do not is not known. Recent studies have started to unravel risk factors that may help the clinician in the proper management of patients who need NSAID under this perspective.

Lesions induced by Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in the distal gastrointestinal tract

The prevalence of NSAID-associated lower GI side effects, including both clinical and subclinical side effects, may exceed those detected in the upper GI tract and include a wide spectrum of lesions ( Table 1 ).

| Adverse Effect | Frequency (%) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Increased gut permeability | 44–70 | |

| Gut inflammation | 60–70 | |

| Blood loss and anemia | 30 | |

| Malabsorption | 40–70 | |

| Protein loss | 10 | |

| Mucosal ulceration | 30–40 | |

| Complications requiring hospitalizations | 0.3–0.9 | |

| Diaphragms of the small bowel | <1 |

Increased Permeability and Inflammation

Subclinical mucosal damage is very frequent in the distal GI tract since at least 60% to 70% of patients taking NSAIDs develop enteropathy. The two most frequent abnormalities are the presence of increased gut permeability and mucosal inflammation. Increased gut permeability can be seen as soon as 12 hours after the ingestion of single doses of most tNSAIDs. The process is rapidly reverted in 12 hours, but it takes longer with continued NSAID use. The administration of prostaglandins reduces or eliminates the damage initially, but this effect is rapidly overcome by the enterohepatic circulation of the NSAIDs.

The increase in gut permeability is not observed with all NSAIDs, because those that do not undergo enterohepatic recirculation may not have this effect. It is now clear that long-term ingestion of most conventional NSAIDs (indomethacin, piroxicam, naproxen, ibuprofen, sulindac), except nabumetone and probably aspirin, increase intestinal permeability. The possible reasons for the lack of small intestinal inflammation associated with nabumetone and aspirin may relate to their site of absorption and lack of excretion in bile. Aspirin, an acidic NSAID, is mostly absorbed through the gastroduodenal mucosa, whereas nabumetone is nonacidic and therefore not trapped within enterocytes during drug absorption. Short-term studies with COX-2 selective inhibitors have shown that these agents do not increase intestinal permeability, suggesting that either dual COX or COX-1 inhibition is a requisite to induce damage to the small bowel.

Animal data have shown an increase in intestinal TNF-α production soon after NSAID administration, which suggests that the presence of intestinal inflammation is rapid following increased gut permeability. Different studies have shown that NSAIDs increase fecal calprotectin (a nondegraded neutrophil cytosolic protein) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis taking NSAIDs. These tests have shown that intestinal inflammation is present in 60% to 70% of patients taking NSAIDs and that, once established, it may be detected up to 1 to 3 years after the NSAID has been stopped. An initial increase in small intestine permeability is a prerequisite of the subsequent development of small intestine inflammation, which is associated with blood and protein loss, but it is often silent.

Blood Loss and Anemia

NSAID enteropathy is associated with continuous and mild bleeding. In the longer term, this may result in iron deficiency and anemia. Although anemia is frequent in patients taking NSAIDs, no studies have been performed to determine the exact burden and clinical impact of this problem in patients taking NSAIDs or aspirin. Furthermore, in many instances, there is no close relationship between demonstrable lesions on the upper GI tract and GI blood loss.

In other situations, patients taking NSAIDs or aspirin may develop anemia, with or without positive fecal occult blood test, but the usual upper or lower GI endoscopic procedures do not show mucosal lesions, suggesting that the small bowel could be the cause of the blood loss. The significance of the presence of isolated mucosal lesions in the small bowel and anemia has not, however, been properly defined. Using enteroscopy, Morris and colleagues investigated the site of blood loss in patients on NSAIDs for rheumatoid arthritis with chronic iron deficiency anemia who had negative gastroscopy and colonoscopy findings. They showed that 47% of these patients had small bowel ulcerations and concluded that this contributed to their anemia. The amount of blood loss from the small intestine is in most cases modest, between 2 and 10 mL/d. The study of subclinical blood loss has methodological problems (long transit times, collection of stool samples, methods for measuring radioactivity in blood and stool, etc) that have not yet been solved.

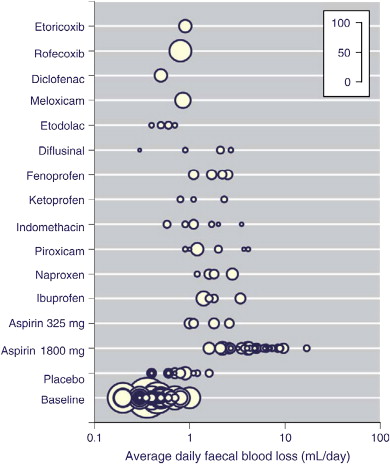

In a systematic review including 1162 individuals in 47 trials conducted over 5 decades, Moore and colleagues found that most NSAIDs and low-dose (325 mg) aspirin resulted in a small average increase in fecal blood loss of 1 to 2 mL/d from about 0.5 mL/d at baseline ( Fig. 1 ). Some individuals lost much more blood than average, at least for some of the time, with 5% of those taking NSAIDs having a daily blood loss of 5 mL or more and 1% having a daily blood loss of 10 mL or more; rates of daily blood loss of 5 mL/d or 10 mL/d were 31% and 10%, respectively, for aspirin at daily doses of 1800 mg or greater. A small comparative study of misoprostol and no treatment in 21 patients with small bowel enteropathy and iron deficiency anemia showed a rise of 15 g/L in hemoglobin with misoprostol compared with no change without treatment.

Malabsorption, Protein Loss, and Ileal Dysfunction

Patients with NSAID enteropathy may have a protein-losing enteropathy, which can lead to hypoalbuminemia. Some studies have shown a loss of proteins labeled with 51 chromium in patients on long-term NSAID therapy at the ileum level, demonstrating the presence of a protein-losing enteropathy. Low serum albumin is found in about 10% of hospitalized patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

NSAIDs do not cause malabsorption when given short term, but malabsorption of D-xylose has been documented in patients on long-term NSAID treatment. Some studies suggest that up to 40% to 70% of patients using NSAIDs may have some degree of intestinal malabsorption. The use of sulindac and fenamates has been associated with severe malabsorption and atrophic mucosa similar to that seen in celiac sprue. NSAID use increases the risk of acute diarrhea, which can be the factor responsible for many episodes seen in general practice.

Mucosal Ulceration

Capsule endoscopy studies have now shown that NSAIDs induce intestinal ulceration in the small bowel, confirming previous autopsy data. Enteroscopic detection of NSAID damage is very frequent and includes edema, erythema, villous denudation, mucosal hemorrhage, erosions, or ulcers. Some reports suggest that this type of lesions are very frequent and can be seen in up to 40% of rheumatic patients taking NSAIDs. The clinical significance of these findings are not yet clear, since most endoscopic mucosal lesions are just petechia or erosions. It is very possible that the clinical considerations usually referred to the upper GI tract, where erosions and acute mucosal lesions are often seen in patients taking NSAIDs but have very little clinical consequences, can also be applied to lesions seen in the small bowel. In any case, it may well be possible that ulcers and erosions of the small bowel could explain why some patients on NSAIDs or low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) (asprin) develop bleeding of “unknown” source, iron deficiency anemia, hypoalbuminemia, or even abdominal symptoms, particularly if the upper and lower endoscopy studies are normal.

Colonoscopy studies have also shown that NSAID use is associated with isolated colonic ulcers, diffuse colonic ulceration that may or may not be associated with occult bleeding, or complications such as major GI bleeding and or perforation. Diffuse colitis has been observed after the use of mefenamic acid, ibuprofen, piroxicam, naproxen, or aspirin. Up to 30% of patients who receive NSAID therapy via the rectum may show some kind of discomfort. More rarely, proctitis, ulceration, bleeding, or rectal stricture have also been described.

NSAIDs may exacerbate pre-existing lesions, including diverticulitis, reactivation of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), and intestinal bleeding from angiodysplastic lesions. Patients with IBD frequently have extraintestinal manifestations, including colitis-associated arthritis, sacroileitis, and ankylosing spondylitis The treatment of these rheumatologic conditions with nonselective NSAIDs has been reported to lead to frequent disease exacerbation. It should be acknowledged that these data are of poor quality and therefore the exact effect of tNSAIDs in the exacerbation of IBD is unclear based on the available evidence. Whether the selective COX-2 inhibitors can be used safely in the setting of IBDs is controversial. A 2006 study has shown that therapy with celecoxib for up to 14 days did not have a greater relapse rate than placebo in patients with ulcerative colitis in remission.

To spare gastroduodenal damage, some NSAIDs have been formulated as enteric-coated compounds and are released in the small bowel. Endoscopic studies have shown that these compounds are associated either with reduced or no damage to the gastroduodenal mucosa but can increase the exposure and toxicity of the active drug to the distal intestine.

Diaphragms

Another rare and unique complication of NSAID use is the development of multiple, concentric, luminal protrusions of fibrotic mucosa and submucosa, nearly occluding the lumen. The term “diaphragm disease” was coined by Lang and colleagues, who were the first to describe the entity, and is considered by many to be pathognomonic for NSAID-related injury, although a case report not finding a relationship with NSAID use has been published. The strictures are diaphragm-like rings of scar tissue and are a distinguishable pathologic entity, which may have a silent clinical evolution or more often induce obstruction, anemia, and/or diarrhea and require surgery for treatment and/or diagnosis. Due to the potential existence of several concomitant rings in other parts of the intestine, it is important to perform a full examination of the small and large intestine, including an intraoperative enteroscopy.

The diaphragms are about 2- to 4-mm thick and can significantly reduce the small bowel lumen diameter, resulting in different degrees of bowel obstruction. Kessler and colleagues reported that 17% of patients with NSAID-induced small bowel ulceration developed intestinal obstruction. There are also numerous case reports of NSAID-induced small bowel and colonic strictures. With the capsule enteroscopy technique, new cases are being discovered, and today, this complication may well overcome other GI complications related to NSAID use (eg, gastric outlet obstruction).

Lesions induced by Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in the distal gastrointestinal tract

The prevalence of NSAID-associated lower GI side effects, including both clinical and subclinical side effects, may exceed those detected in the upper GI tract and include a wide spectrum of lesions ( Table 1 ).

| Adverse Effect | Frequency (%) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Increased gut permeability | 44–70 | |

| Gut inflammation | 60–70 | |

| Blood loss and anemia | 30 | |

| Malabsorption | 40–70 | |

| Protein loss | 10 | |

| Mucosal ulceration | 30–40 | |

| Complications requiring hospitalizations | 0.3–0.9 | |

| Diaphragms of the small bowel | <1 |

Increased Permeability and Inflammation

Subclinical mucosal damage is very frequent in the distal GI tract since at least 60% to 70% of patients taking NSAIDs develop enteropathy. The two most frequent abnormalities are the presence of increased gut permeability and mucosal inflammation. Increased gut permeability can be seen as soon as 12 hours after the ingestion of single doses of most tNSAIDs. The process is rapidly reverted in 12 hours, but it takes longer with continued NSAID use. The administration of prostaglandins reduces or eliminates the damage initially, but this effect is rapidly overcome by the enterohepatic circulation of the NSAIDs.

The increase in gut permeability is not observed with all NSAIDs, because those that do not undergo enterohepatic recirculation may not have this effect. It is now clear that long-term ingestion of most conventional NSAIDs (indomethacin, piroxicam, naproxen, ibuprofen, sulindac), except nabumetone and probably aspirin, increase intestinal permeability. The possible reasons for the lack of small intestinal inflammation associated with nabumetone and aspirin may relate to their site of absorption and lack of excretion in bile. Aspirin, an acidic NSAID, is mostly absorbed through the gastroduodenal mucosa, whereas nabumetone is nonacidic and therefore not trapped within enterocytes during drug absorption. Short-term studies with COX-2 selective inhibitors have shown that these agents do not increase intestinal permeability, suggesting that either dual COX or COX-1 inhibition is a requisite to induce damage to the small bowel.

Animal data have shown an increase in intestinal TNF-α production soon after NSAID administration, which suggests that the presence of intestinal inflammation is rapid following increased gut permeability. Different studies have shown that NSAIDs increase fecal calprotectin (a nondegraded neutrophil cytosolic protein) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis taking NSAIDs. These tests have shown that intestinal inflammation is present in 60% to 70% of patients taking NSAIDs and that, once established, it may be detected up to 1 to 3 years after the NSAID has been stopped. An initial increase in small intestine permeability is a prerequisite of the subsequent development of small intestine inflammation, which is associated with blood and protein loss, but it is often silent.

Blood Loss and Anemia

NSAID enteropathy is associated with continuous and mild bleeding. In the longer term, this may result in iron deficiency and anemia. Although anemia is frequent in patients taking NSAIDs, no studies have been performed to determine the exact burden and clinical impact of this problem in patients taking NSAIDs or aspirin. Furthermore, in many instances, there is no close relationship between demonstrable lesions on the upper GI tract and GI blood loss.

In other situations, patients taking NSAIDs or aspirin may develop anemia, with or without positive fecal occult blood test, but the usual upper or lower GI endoscopic procedures do not show mucosal lesions, suggesting that the small bowel could be the cause of the blood loss. The significance of the presence of isolated mucosal lesions in the small bowel and anemia has not, however, been properly defined. Using enteroscopy, Morris and colleagues investigated the site of blood loss in patients on NSAIDs for rheumatoid arthritis with chronic iron deficiency anemia who had negative gastroscopy and colonoscopy findings. They showed that 47% of these patients had small bowel ulcerations and concluded that this contributed to their anemia. The amount of blood loss from the small intestine is in most cases modest, between 2 and 10 mL/d. The study of subclinical blood loss has methodological problems (long transit times, collection of stool samples, methods for measuring radioactivity in blood and stool, etc) that have not yet been solved.

In a systematic review including 1162 individuals in 47 trials conducted over 5 decades, Moore and colleagues found that most NSAIDs and low-dose (325 mg) aspirin resulted in a small average increase in fecal blood loss of 1 to 2 mL/d from about 0.5 mL/d at baseline ( Fig. 1 ). Some individuals lost much more blood than average, at least for some of the time, with 5% of those taking NSAIDs having a daily blood loss of 5 mL or more and 1% having a daily blood loss of 10 mL or more; rates of daily blood loss of 5 mL/d or 10 mL/d were 31% and 10%, respectively, for aspirin at daily doses of 1800 mg or greater. A small comparative study of misoprostol and no treatment in 21 patients with small bowel enteropathy and iron deficiency anemia showed a rise of 15 g/L in hemoglobin with misoprostol compared with no change without treatment.

Malabsorption, Protein Loss, and Ileal Dysfunction

Patients with NSAID enteropathy may have a protein-losing enteropathy, which can lead to hypoalbuminemia. Some studies have shown a loss of proteins labeled with 51 chromium in patients on long-term NSAID therapy at the ileum level, demonstrating the presence of a protein-losing enteropathy. Low serum albumin is found in about 10% of hospitalized patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

NSAIDs do not cause malabsorption when given short term, but malabsorption of D-xylose has been documented in patients on long-term NSAID treatment. Some studies suggest that up to 40% to 70% of patients using NSAIDs may have some degree of intestinal malabsorption. The use of sulindac and fenamates has been associated with severe malabsorption and atrophic mucosa similar to that seen in celiac sprue. NSAID use increases the risk of acute diarrhea, which can be the factor responsible for many episodes seen in general practice.

Mucosal Ulceration

Capsule endoscopy studies have now shown that NSAIDs induce intestinal ulceration in the small bowel, confirming previous autopsy data. Enteroscopic detection of NSAID damage is very frequent and includes edema, erythema, villous denudation, mucosal hemorrhage, erosions, or ulcers. Some reports suggest that this type of lesions are very frequent and can be seen in up to 40% of rheumatic patients taking NSAIDs. The clinical significance of these findings are not yet clear, since most endoscopic mucosal lesions are just petechia or erosions. It is very possible that the clinical considerations usually referred to the upper GI tract, where erosions and acute mucosal lesions are often seen in patients taking NSAIDs but have very little clinical consequences, can also be applied to lesions seen in the small bowel. In any case, it may well be possible that ulcers and erosions of the small bowel could explain why some patients on NSAIDs or low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) (asprin) develop bleeding of “unknown” source, iron deficiency anemia, hypoalbuminemia, or even abdominal symptoms, particularly if the upper and lower endoscopy studies are normal.

Colonoscopy studies have also shown that NSAID use is associated with isolated colonic ulcers, diffuse colonic ulceration that may or may not be associated with occult bleeding, or complications such as major GI bleeding and or perforation. Diffuse colitis has been observed after the use of mefenamic acid, ibuprofen, piroxicam, naproxen, or aspirin. Up to 30% of patients who receive NSAID therapy via the rectum may show some kind of discomfort. More rarely, proctitis, ulceration, bleeding, or rectal stricture have also been described.

NSAIDs may exacerbate pre-existing lesions, including diverticulitis, reactivation of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), and intestinal bleeding from angiodysplastic lesions. Patients with IBD frequently have extraintestinal manifestations, including colitis-associated arthritis, sacroileitis, and ankylosing spondylitis The treatment of these rheumatologic conditions with nonselective NSAIDs has been reported to lead to frequent disease exacerbation. It should be acknowledged that these data are of poor quality and therefore the exact effect of tNSAIDs in the exacerbation of IBD is unclear based on the available evidence. Whether the selective COX-2 inhibitors can be used safely in the setting of IBDs is controversial. A 2006 study has shown that therapy with celecoxib for up to 14 days did not have a greater relapse rate than placebo in patients with ulcerative colitis in remission.

To spare gastroduodenal damage, some NSAIDs have been formulated as enteric-coated compounds and are released in the small bowel. Endoscopic studies have shown that these compounds are associated either with reduced or no damage to the gastroduodenal mucosa but can increase the exposure and toxicity of the active drug to the distal intestine.

Diaphragms

Another rare and unique complication of NSAID use is the development of multiple, concentric, luminal protrusions of fibrotic mucosa and submucosa, nearly occluding the lumen. The term “diaphragm disease” was coined by Lang and colleagues, who were the first to describe the entity, and is considered by many to be pathognomonic for NSAID-related injury, although a case report not finding a relationship with NSAID use has been published. The strictures are diaphragm-like rings of scar tissue and are a distinguishable pathologic entity, which may have a silent clinical evolution or more often induce obstruction, anemia, and/or diarrhea and require surgery for treatment and/or diagnosis. Due to the potential existence of several concomitant rings in other parts of the intestine, it is important to perform a full examination of the small and large intestine, including an intraoperative enteroscopy.

The diaphragms are about 2- to 4-mm thick and can significantly reduce the small bowel lumen diameter, resulting in different degrees of bowel obstruction. Kessler and colleagues reported that 17% of patients with NSAID-induced small bowel ulceration developed intestinal obstruction. There are also numerous case reports of NSAID-induced small bowel and colonic strictures. With the capsule enteroscopy technique, new cases are being discovered, and today, this complication may well overcome other GI complications related to NSAID use (eg, gastric outlet obstruction).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree