Nonresectional and Resectional Rectopexy

Scott R. Steele

Robert D. Madoff

Full-thickness external rectal prolapse can be a distressing condition for both the patient and the surgeon alike. In addition to its unsightly and at times alarming appearance, rectal prolapse may cause progressive symptoms that affect both a patient’s overall medical health and the quality of life (1). Full external prolapse occurs when the rectum descends beyond the anal verge, manifesting as concentric rings of rectal mucosa to the examiner. Severity varies, as the prolapse may progress from initial reduction with standing or cessation of straining, to full-thickness prolapse with even minimal activity, and finally, in certain cases, to continual prolapse. As time passes, chronic prolapse through the sphincter complex, along with the presence of concomitant pelvic floor dysfunction, can lead to problems with both continence and symptoms of constipation from outlet obstruction. When considering indications for intervention, it is important to distinguish overt from internal rectal prolapse (also known as hidden or occult intussusception) in which the prolapse contains the full thickness of the rectal wall but the intussusception does not extend beyond the anal verge.

Factors to consider in selecting the ideal therapeutic approach include the age and health of the patient, overall functional status, and the potential benefits and risks of a given surgical technique (2). In general, transabdominal procedures are recommended for fit patients, as they are associated with the lowest recurrence rates (3,4). Transperineal procedures are generally reserved for older patients and those with comorbid conditions who would gain the most benefit from a limited operation that is associated with lesser morbidity, a shorter length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery. Unfortunately, perineal repairs are not as durable as the transabdominal procedures, with reported recurrence rates of 16-40% depending on the particular procedure and follow-up time 5,6). Other factors may also play a role in procedure selection, such as the risk of sexual dysfunction from autonomic nerve damage during the pelvic dissection with an abdominal procedure.

The goal of abdominal rectopexy is to restore the rectum to its normal position in the pelvis by fixing it to the presacral fascia. This approach restores the normal posterior curve of the rectum in the hollow of the sacrum, though the physiologic benefits of this restoration are uncertain. Open abdominal rectopexy can be easily performed with or without resection of the redundant sigmoid colon.

While the main indication for prolapse repair is to address specific symptoms (mass, mucus discharge, incontinence, impaired defecation), the mere presence of rectal prolapse is reason enough to recommend repair because of the likely eventual progression of symptoms, particularly incontinence due to sphincter dysfunction, as well as a small risk of incarceration. Rectopexy is much less likely to alleviate symptoms associated with internal intussusception and is not indicated unless the patient has solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. For those patients with a large redundant sigmoid colon, history of symptomatic diverticular disease, and/or constipation-predominant symptoms, sigmoid resection can be considered as an adjunct to rectopexy.

As this is an open transabdominal approach, patients undergoing consideration for this type of elective repair should be medically fit and able to tolerate a laparotomy. A detailed medical history is vital when evaluating patients with rectal prolapse, including a thorough review of bowel habits, as more than half of patients have coexisting incontinence and slightly fewer patients have constipation. Patients not only frequently report their rectal protrusion but also give a history of problematic bowel habits, abdominal discomfort, and mucus discharge. Many patients strain to initiate or complete defecation, experience incomplete evacuation, or require digital maneuvers to aid with defecation. This may be secondary to the rectal prolapse itself or pelvic floor dysfunction associated with either anatomical defects (rectocele, cystocele, enterocele) or functional abnormalities such as paradoxical or nonrelaxing puborectalis.

In addition to a general physical examination, digital rectal examination can detect the presence of attenuated sphincter tone and masses, as well as assess for concomitant pelvic floor pathology. The patient should be asked to both tighten her anal sphincter and “bear down” as a simulation of defecation to assess proper contraction and relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles. The perineum is assessed for associated increased perineal descent or bulge indicative of pelvic floor laxity that is often seen with increasing age, multiparity, or prior pelvic floor surgery. Examination of the vagina can also be helpful in identifying concomitant pelvic floor abnormalities such as rectocele, cystocele or uterine prolapse that may also need to be addressed.

Preoperative evaluation can include specific physiologic tests and imaging studies on a selective basis. Colonoscopy should be up-to-date for all patients aged 50 years or older and should be performed on a selective basis for younger patients or those with new symptoms since their last examination. Patients who complain of severe constipation with infrequent bowel movements should undergo a colonic transit study. Rectal prolapse patients have a high rate (approximately 15–30%) of concomitant pelvic floor disorders such as abnormal rectal emptying, nonrelaxing pelvic floor, enterocele and rectocele (7). When suggested by history or on physical examination, the dynamics of rectal evacuation and search for these concomitant findings may be studied with multicontrast defecography or dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Anal manometry can serve as a useful baseline assessment for incontinent patients, though the findings rarely change the operative approach. Anal ultrasound can be considered to assess sphincter integrity in patients with associated fecal incontinence.

Nonresectional Rectopexy

Surgery

Prior to the procedure, in many cases, initial preparations for a nonresectional rectopexy consist of a mechanical bowel preparation, which may be often limited to enemas on the morning of surgery according to per physician preference. Preoperative intravenous antibiotics are routinely given and timed for adequate concentration during the initial skin incision. In addition, deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis including sequential compression devices and chemical prophylaxis such as heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin may be considered. In general, the most common types of nonresectional cases include rectal mobilization alone, mobilization with suture rectopexy, and mobilization with rectopexy involving mesh. As each of these have different risk and outcome profiles, preoperative counseling and discussion of the proposed procedure is important.

Positioning

In the operating room, the patients are positioned in the modified lithotomy position to provide access to the anus and the rectum, as well as to provide ideal positioning for retraction of the bladder, prostate, or vagina. Both the surgeon and the assistant should wear headlights to facilitate visualization during the pelvic dissection. Ureteral catheters may be especially helpful in patients who have had prior radiation, pelvic surgery, or adhesive disease, but their routine use is not necessary. All bony prominences are well padded and consideration should be given for a pad under the sacrum. Per physician preference, both arms may be tucked at the patient’s side or extended for monitoring access.

Open Technique

The basic tenets of the abdominal approach include mobilization of the rectum to the pelvic floor with sacral suspension to hold it in place until it scars into position. The operation commences with a midline incision from the umbilicus to the pubis or a lower transverse (Pfannenstiel) incision; each of these incisions provides adequate exposure for most patients. After placement of self-retaining retractors, the small bowel is displaced superiorly and packed into the upper abdomen. Posterior mobilization is carried down to the level of the coccyx in the anatomic mesorectal plane. Proper identification of the avascular presacral plane is aided by application of forward traction on the rectum. Care is taken to preserve the hypogastric nerves at the level of the sacral promontory. Unintentional division of the hypogastric nerves, typically at the level of the inferior mesenteric artery takeoff or at the level of the sacral promontory, can cause sexual and urinary dysfunctions.

The proper amount of lateral and anterior dissection is subject to debate. Surgeons frequently discuss dividing the “lateral ligaments” or fixing them to the sacrum, but these ligaments do not exist as true anatomic structures. Thus, while failure to divide the lateral ligaments was shown to increase the recurrence rate in one small, randomized trial, exactly what structure was being divided is uncertain. Furthermore, the functional outcome of lateral ligament division is subject to debate: some authors have shown a worsening of constipation, but others have found no change in postoperative bowel function (8).

Anterior mobilization of the rectum allows it to be further displaced out of the pelvis, but its efficacy in preventing relapse or improving functional outcome is unknown. The anterior mobilization of the rectum begins with division of the peritoneal reflection. Dissection between the anterior aspect of the rectum and the posterior aspect of the anterior pelvic structures is facilitated by anterior retraction of the uterus or the bladder with a St. Mark’s or a Wylie retractor, whereas posterior countertraction

on the rectum is maintained by the surgeon’s left hand. We generally carry our anterior dissection to the level of the mid to upper third of the vagina; more distal dissection, especially in men, increases the risk of parasympathetic nerve injury.

on the rectum is maintained by the surgeon’s left hand. We generally carry our anterior dissection to the level of the mid to upper third of the vagina; more distal dissection, especially in men, increases the risk of parasympathetic nerve injury.

Rectal Mobilization Alone

In this procedure, mobilization of the rectum to the pelvic floor alone is performed as above, however there is no dedicated maneuver for sacral suspension. Rather, proponents feel the healing process that follows mobilization alone provides adequate ability for scar tissue to form and hold the rectum in place to avoid recurrence.

Suture Rectopexy

During the initial mobilization, emphasis is again placed on carrying the posterior dissection down to the level of the coccyx in the anatomic avascular mesorectal plane, preserving the hypogastric nerves, and opening the plane anterior to the rectum to varying extents based upon surgeon preference.

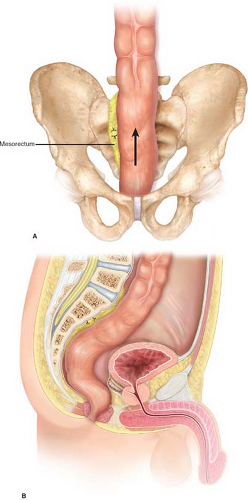

The rectopexy is then performed by first choosing a point approximately 4–5 cm below the sacral promontory for the inferior-most aspect of fixation. The rectum is then pulled posterior and superiorly toward the sacrum and the site for rectal fixation is chosen. The goal is to suspend the rectum without redundancy below the rectopexy sutures; excessive tension on the distal rectum should be avoided. While some authors advocate placement of fixation sutures on either side of the rectum, we prefer to place all the sutures on one side, because this approach avoids kinking of the rectum at the site of the rectopexy. We use two 2-0 Prolene mattress sutures, passed anterior to posterior through the mesorectum adjacent to the bowel wall, then through the presacral fascia, and finally back through the mesorectum (posterior to anterior) 1.5–2 cm from the initial bite. (Fig. 54.1A and B) Care must be taken to avoid both impalement of mesenteric vessels and injury to the presacral venous plexus. It is worth noting that the sutures’ role is to provide temporary fixation until fibrosis from the scarring process fixes the rectum into place. The peritoneum is left open, and we do not routinely drain the pelvis. The abdominal wall is closed in layers once meticulous hemostasis has been ensured.

Mesh Rectopexy

Similar to the other nonresectional techniques, the rectal mobilization is as described above. However, in this case the mesh is placed to provide additional point of fixation and scarring to the sacral promontory. Various types of meshes have been described from polypropylene and PTFE to biologics. Similarly the mesh has been used in both posterior and anterior locations, as well as varying degrees of circumferential or partial wrapping of the rectum itself.

For a posteriorly based wrap, once the rectum has been fully mobilized, a rectangular-shaped piece of mesh is secured to the presacral fascia (Figs. 54.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree