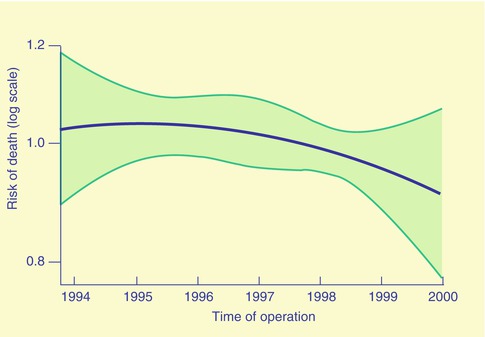

Fig. 2.1

Risk of local recurrence for radically treated rectal cancer patients in Norway during the first years of the project (log scale) (© (2006) Blackwell Publishing Ltd. on behalf of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland)

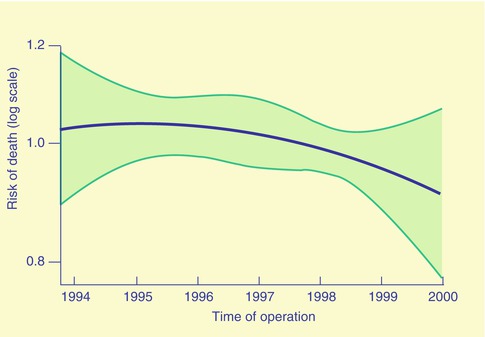

At the same time, the overall survival for radically treated rectal cancer patients had increased from 55 % prior to the project to 71 % in the period 1993–1999 (for patients younger than 75 years) (Fig. 2.2) [16, 17].

Fig. 2.2

Risk of death of any cause for radically treated rectal cancer patients in Norway during the first years of the project (log scale) (© (2006) Blackwell Publishing Ltd. on behalf of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland)

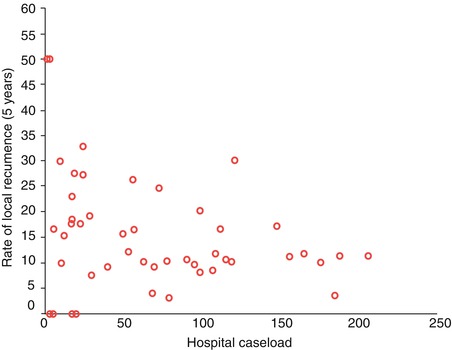

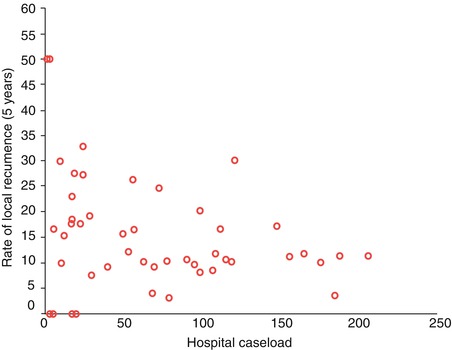

What could explain such immediate response? As only 9 % of the patients had radiotherapy and 2 % had chemotherapy, it was obvious that improved surgery had to be the major contributor to the better results. But, there was a huge variation of results between hospitals and also between types of hospitals (Fig. 2.3). The smallest hospitals had doubled the rate of local recurrence and a significant lower survival compared to the largest hospitals. The 5-year local recurrence rates were 17.5 and 9.2 % (p = 0.003), and the 5-year overall survival rates were 57.8 and 64.4 % (p = 0.105), respectively, in hospitals with annual caseload less than ten compared to more than 30 [18]. These analyses even strengthened the message that surgery had to be the single most important part of the treatment, as half of the hospitals had to perform better than the mean within each group. What did they do different than the hospitals not performing that well?

Fig. 2.3

Local recurrence at each hospital in Norway related to hospital caseload in the period November 1993–December 1999 [16] (© (2006) Blackwell Publishing Ltd. on behalf of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland)

Despite the comprehensive educational programme going on from 1993 to 1996, where gastrointestinal surgeons were taught the principles of TME, it was clear that there was a need to continue the project as a continuous quality assurance programme for rectal cancer. Again regular national workshops were started, including not only live TME surgery but also detailed education in comprehensive preoperative work-up radiology, oncological therapy and pathology. The strategy of the project included systematic training and accreditation of surgeons, ending up with specialised dedicated teams responsible for rectal cancer treatment. The national programme stated that multidiscipline preoperative and postoperative evaluations were mandatory for quality assurance of rectal cancer treatment.

Turning the second millennium, it was obvious that the Norwegian Rectal Cancer Registry contained data that were most important also for the international community. Several study groups were established, and both surgeons and oncologists started as research fellows. The study groups were recruited from every health region, each analysing different topics of rectal cancer treatment. Thus, no competition developed, and the board of the project gained even more support from all over the country. At that time, the project had changed, from a time set developing project, moving on to permanent quality assurance for one of the most common cancer diseases. From 2000 the project has been funded by the Ministry of Health.

Why had the project succeeded? There may be many reasons for that. First of all, the project was initiated by the clinicians themselves, those doing the work, treating the patients and delivering the data. If this project had been pushed onto the clinicians by the health-care authorities, it may have failed. Secondly, all the clinicians received their own results, i.e. the result of their hospital, and the national means for comparison. That had never happened before in their professional life. In addition, every hospital receives all their data back for their own scientific purpose, thus stimulating to publish their own results, which often happens, especially during the annual national surgical week. Although the results of single hospitals so far have been anonymously reported from the national registry, many hospitals prefer to publish their own data. This feedback of data is a true win-win situation, supporting both the national project and the standard of treatment at each hospital. Another benefit of feedback of results is that underperforming departments make every possible effort in order to catch up with the best performing hospitals. Detailed analyses for single hospitals enable them to identify what may cause inferior results and/or violation of national guidelines.

Thirdly, the board of the project includes experts from different specialities working together towards a common goal. That has increased the competence of the group, securing the development of the project heading in a direction based on international science.

During national workshops the multidisciplinary collaboration of the board has been transferred to each hospital. The clinicians have picked up knowledge and competence from different specialities, showing the necessity of clinicians working together across different specialities. The future of the patient is their common goal.

Another main issue for the success was that the decision of taking part in the national rectal cancer registry was left to the discretion of each hospital. Apart from the compulsory reporting of the standard dataset to the main cancer registry, every hospital was invited to report their detailed data of treatment and follow-up of their rectal cancer patients.

During the first years of the project, although every hospital wanted to take part in the project, a few of the 55 hospitals treating rectal cancer did not report their own data, and the central staff of the project visited these hospitals and collected missing data. However, following the first feedback of results to each hospital, reporting of data has been smooth.

The board has no formal responsibility for the treatment given at each hospital, neither have the members of the board any knowledge of the results of single hospitals. Such results are only known by the office staff. Thus, the board has always voiced that the head of the department is responsible for the quality of care.

One main policy of the project has been that no directives are to be sent to the hospitals, neither from the staff nor from the board. But, based on international and national data, nationwide guidelines have been regularly revised [19].

During the first years of the project, it became obvious that surgery for rectal cancer should be performed by fewer surgeons specially trained in the TME technique. Thus, it was necessary to change the educational programme for general surgery and to remove rectal cancer surgery from the programme. The professional community recommended that rectal cancer procedures only should be performed by specialists in gastrointestinal surgery. A few years later, following the report showing a wide variation of results between hospitals, the regional health-care authorities decided that rectal cancer patients only should be treated by multidisciplinary teams at central hospitals and university hospitals. Although most general surgeons at local hospitals already had ceased rectal cancer surgery due to their very bad results during the first years of the project, some surgeons at small hospitals had to be convinced that without a team of dedicated specially trained experts, many rectal cancer patients would not be cured. Thus, the results of single hospitals changed clinical practice all over the country, and most of this change was initiated by the process itself. Ten years after the project started, rectal cancer treatment had been centralised to less than half of Norwegian hospitals. That solved the problem of missing competence related to low caseload, but what about larger hospitals with bad results?

Reorganising of the whole treatment line was performed at several large hospitals. One example of that was the development of modern treatment principles at Haugesund Central Hospital. In the first 5 years of the project, the rate of local recurrence was 31.5 % at this hospital. The staff was reorganised, and they made several initiatives to improve their standards of care. They attended the national workshops; they got some new retractors for the procedure; they followed the national guidelines for neoadjuvant therapy; CT, rectal ultrasound and MRI became routine for preoperative work-up; a multidisciplinary team was established; and a small dedicated group of specialists in gastrointestinal surgery performed the procedures. In the next 3-year period, their local recurrence was 11 %, later 6 %, and since 2005 none of their patients have developed local recurrence [20]. Similarly, at Levanger Hospital, they had 19 % local recurrence during the 1990s, but, after receiving their results from the national project, the staff came aware of their inferior standards, and in the following period, 2000–2004, they managed to reduce their local recurrence rate to 2 % (p = 0.006) [21]. In other words, due to the national project, every hospital has got a tool to discover missing standards and to develop their competence and skills through close collaboration with staff members of the project.

The project resulted in much focus on cancer surgery. Newspapers and television companies got interested in the results, especially the wide variation in standards of care between hospitals. That became a political issue which seemed to ease project funding from the Ministry of Health. Similarly, the health-care bureaucracy at the hospital, regional and national level regularly receives results from the project, which seems to have been important in order to keep focus on standards of cancer care in general, and specific regulations for treatment of all gastrointestinal cancers have been implemented all over the country.

European Experience

The Swedish Rectal Cancer Registry was established in 1995. The collection of data is based on regional cancer registries, but complete national rectal cancer analyses are performed on similar data sets as in Norway. The Swedish project is based on similar workshops as in Norway, with live video demonstrations of TME surgery by Dr. Heald. Although the surgical communities in Norway and Sweden have had close collaboration for decades, their treatment policies for rectal cancer have been different. Since the randomised Swedish studies [21, 22], their philosophy for treating rectal cancer has been based on short-course preoperative radiotherapy of 5 × 5 Gy to most patients and long course with 54 Gy for advanced cases, in contrast to Norway with a tailored treatment policy, with long-course radiotherapy only for advanced cases and no radiotherapy for >90 % of the patients. How could these different guidelines be implemented? May be the explanation is that the literature was interpreted differently. In Norway a nationwide audit of rectal cancer treatment for the period 1986–1988 told us that the prognosis was bad in general, but single-hospital studies showed a huge variation of results between hospitals. Furthermore, rectal cancer surgery was performed by 245 surgeons with an annual median number of one procedure per year [12]. Then, in Norway we trusted the reports from Heald [6] and Bjerkeset [13], both with 4 % local recurrence and almost without any use of radiotherapy. When no other therapy was given and the results were different, there was no other explanation but the standard of surgery had to play the major role for local recurrence and survival. Another reason for not using radiotherapy as routine treatment for rectal cancer was the well-known acute and late toxicity.

That information made the basis of the Norwegian strategy implementing the principle of tailored treatment of the tumour and the patient. The Norwegian surgical and oncological community agreed that routine radiotherapy for all or most rectal cancer patients would imply overtreatment and severe complications resulting in reduced functional outcomes and unnecessary loss of lives. A meta-analysis from the UK of more than 8,500 patients confirmed this view. Radiotherapy increased the risk of death from nonrectal cancer by 15 %, mainly due to vascular and infective complications [23]. For patients over 75 years, there were more side effects than beneficial effects of radiotherapy.

In Sweden the professional surgical and oncological community had experienced a considerable effect of radiotherapy in reducing local recurrence, from 27 to 11 % [22]. It was also thought that preoperative short-course radiotherapy for 1 week and surgery the next week would result in less toxicity and postoperative complications, but with the same positive effect on reducing local recurrence as the long-course schedule.

Although Norway and Sweden established national rectal cancer projects almost simultaneously, in 1993 and 1995, respectively, and with the same professional support, their treatment policies were different. Interestingly, in Norway in 1997, 12 % of the patients had radiotherapy, compared to 55 % in Sweden. But the national mean rates of local recurrence and overall survival were similar in the two countries (10 % and 9 %, and males 62 % and females 58 % and males 56 % and females 56 %, in Norway and Sweden, respectively) [24].

In Denmark a national rectal cancer registry was developed in 1994 [25], and Belgium started a comprehensive registration in 2007 [26]. Since 2006 the Spanish Association of Surgeons has arranged similar workshops as in Norway and Sweden, and a registry is now covering 1/3 of the Spanish rectal cancer patients [27]. Seventy of the largest hospitals in Spain are now included in this initiative. For some years a German-Polish collaboration are collecting data on rectal cancer patients [28], and in 2008 a Dutch national colorectal cancer registry was launched [29]. In Great Britain a colorectal cancer registry is based on administrative data [30]. Although these registries may not have the exact same type of data, all these registries are established with the same goal. All the work with workshops, collecting data, analyses and reporting are established and run by clinicians in order to improve the prognosis of rectal cancer patients. Have all these efforts had any effect on patients’ life expectancy? In Norway and Sweden it has had a considerable effect. Before the projects started, the prognosis of rectal cancer was substantially worse compared to colon cancer; now patients with rectal cancer have better survival than those with colon cancer.

Multidisciplinary Meeting and Treatment

That radiotherapy has beneficial effect on rectal cancer in reducing local recurrence has been known for decades, but in the era of TME this benefit has not been translated into an increased overall survival. In spite of that, in many countries radiotherapy has been used, and still is, for most rectal cancer patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree