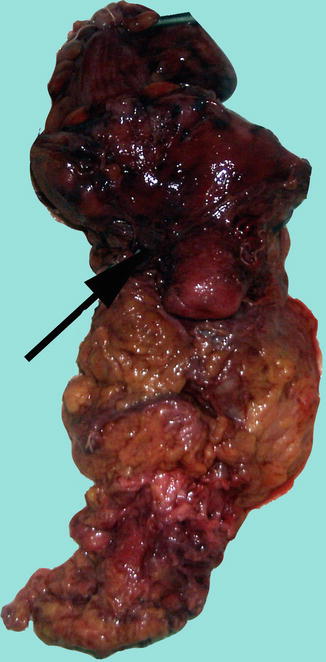

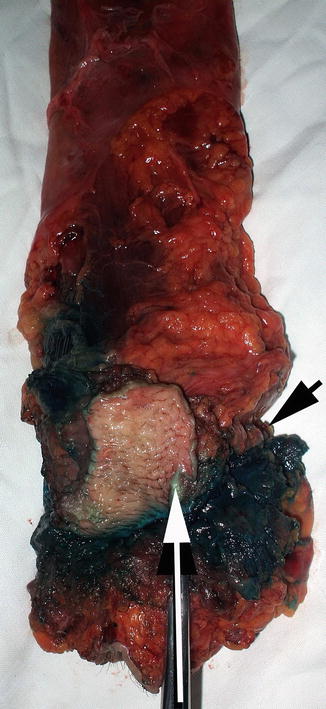

Fig. 9.1

Abdominoperineal fresh-resection specimen (sigmoid, rectum, and anal canal with mesorectal envelope and levator ani excised)

That is the reason why, over time, many surgeons tried to avoid this operation; in declining the number of the APR, there were several events: the paramount importance was the observation that rectal cancer rarely extended beyond 1–1.5 cm from the lower border of the tumor, thus a distal resection limit of 2 cm becoming sufficient oncologically [10, 17, 20]. Once with the development of the stapling devices and also of the neoadjuvant therapies, the feasibility of sphincter-saving procedure has been proved, even for low rectal cancers. Also nowadays, a percentage of the distal T1 or even T2 distal rectal cancer patients may be safely treated by a local excision. As a consequence, the incidence of abdominoperineal resection has started to decrease, limited most often to the distal rectal cancer, but now considered mandatory only in case of anal sphincter involvement by cancer or invasion of the cancer in the levatorian plane, thus no sphincter-preserving surgery is possible anymore (no distal tumoral clearance is possible) (Fig. 9.2).

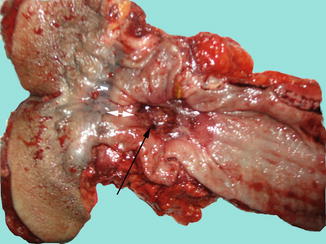

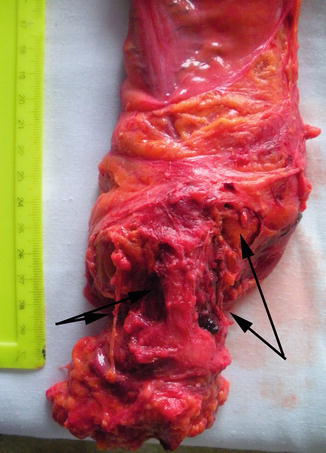

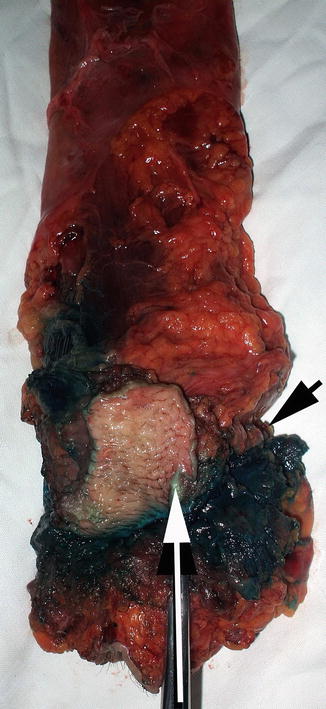

Fig. 9.2

Ulcerated cancer (black arrow) of the distal rectum located just above the dentate line (white arrow). No safe distal resection margin may be achieved – indication for abdominoperineal excision of the rectum (fresh resection specimen)

Excepting for the local extension of the rectal cancer, there are several other factors influencing the decision of performing an APR; the preoperative anal sphincter dysfunction or intraoperative difficulties in performing a very low anastomosis with a high risk of leakage may lead to an APR. These factors have been already discussed by Rothenberger and Wong in their article and have been suffering very few modifications since then [22].

Another reason for that is represented by the postoperative results, with a significantly increased morbidity (55.4 % vs 34.2 %) [1] and a significantly higher length of the hospital stay after APR, when compared to low anterior resection. Also, a higher local recurrence rate and a worst long-distance survival have been reported after APR [8, 12, 14, 24] but these results have been contested by other studies [1, 16].

All of these considerations have made the APR to become an “endangered operation” [8]. This is due especially to Bill Heald and coll., who reported from 1997 only a 23 % of low rectal cancers (below 5 cm from the anal verge, or 1–1.5 cm from the dentate line) treated with APR [8]. The same decline in APR incidence was reported later, by Tilney and coll., who found in England that only 24.9 % of rectal cancers had been treated by APR from 1996 to 2004 [24].

In fact, sphincter-saving procedures became the standard procedure for low rectal cancer in many centers [5]; still, there are significant differences between different surgical centers, with a percentage of 24–38 % of rectal cancer cases requiring an APR [4, 8, 13, 14, 24, 26].

Surgical Technique

From the surgical technique point of view, by definition, the abdominoperineal resection requires an abdominal approach, for vascular ligation and removal of the most part of the sigmoid and rectum, and a perineal approach in order to remove the anal canal, the ischiorectal fat, and the lowest part of the rectum and mesorectum. The operation may be done in one team (as originally described by Miles) or in two synchronous teams (it has the advantage of shortening considerably the time of the operation – Lloyd-Davis) [10, 19].

The preoperative preparations are similar to those described in the anterior resection; maybe much consideration must be given to establish preoperatively the level of the tumor from the anal verge and the impossibility of a sphincter-saving procedure (fixed, bulky tumors, sphincteric or levator invasion on digital examination, rigid rectosigmoidoscopy, MRI, or endorectal ultrasound) and also an indication for neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy; still, in some cases, the final intraoperative assessment will decide over the impossibility of preserving the anal sphincter. In any circumstances, the preoperative psychological implication of the stoma creation must be discussed with the patient, and the place where stoma will be performed on the anterior abdominal wall must be noted, in order to ensure a good coverage by the colostomy device [19].

Abdominal Phase of the Operation

The abdominal phase of the operation is very similar to surgical elements presented at low anterior resection; therefore, in this chapter we will insist only on the particularities of the abdominal approach in APR.

The incision is a midline pubo-umbilical, extended above the umbilicus; some authors prefer a right transrectal or even a transverse infraumbilical incision [10, 22]. Exploration and mobilization of the colon is similar to low anterior resection, but the mobilization of the splenic flexure is not usually needed. The recommended level of vascular ligation is at the origin of the superior rectal artery, just below of the takeoff of the left colic artery [11, 17, 19, 22]; there is no strong evidence that high ligation has a benefit over the mentioned level [11]. Obviously, if enlarged lymph nodes are detected at the superior rectal artery origin, or along it, for oncological reasons are indicated to perform a high-tie, at the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery.

The pelvic dissection is somewhat different in APR: after the sigmoid was divided, the posterior dissection starts in a similar way, as it was described in low anterior resection (total mesorectal excision), using also the nerve-sparing technique. In the classic view, the pelvic dissection had to be as complete as possible, down to the pelvic floor, before the perineal sequence begins [19, 22]. In the modern APR it is better to avoid a very low dissection on the anterior and lateral mesorectum, the pelvic dissection being stopped once the level of the distal rectal tumor has been reached, in order to avoid tumoral cells spillage [4]. This is determined by the levatorian plane shape, which may lead to a conning-in the mesorectum if after the plane of the levator ani is reached, with an increased risk of local recurrent disease (Figs. 9.3 and 9.4). Therefore, after the levatorian plane is reached laterally and seminal vesicles or the prostate base [10] anterior, the dissection must commence from the perineum, much more favorably to a correct dissection, favored by the shape of levator ani.

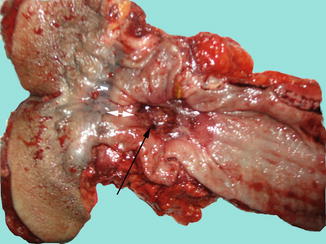

Fig. 9.3

Important coning-in the mesorectum (black arrows) due to the very low pelvic dissection in a distal rectal cancer (fresh resection specimen)

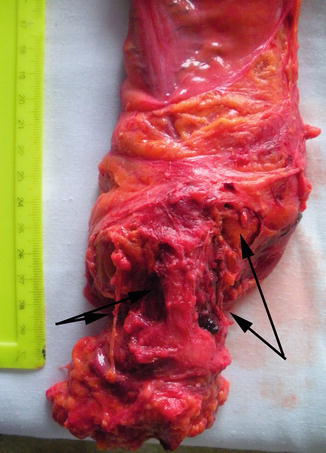

Fig. 9.4

APR with posterior partial colpectomy (white arrow). Black arrow indicates the presence of an area of coning-in the mesorectum due to distal pelvic resection in an inferior rectal cancer (fresh resection specimen)

Perineal Phase of Surgery

The approach in the perineal sequence of the APR depends if the resection is performed by one team or synchronously, by two different surgical teams: in case of synchronous approach, the patient is positioned in modified Lloyd-Davis position (shorter operative time, no repositioning of the patient, and dissection from two planes in bulky tumors, but less visibility and difficult dissection in anterior plane from the abdomen). In case of one team APR, after the abdominal time is over (the colostomy is matured and the abdomen is closed), the patient is turned into the prone, jackknife position [10]. The rectum is irrigated with povidone-iodine solution, after which the anus is closed in a purse-string suture (otherwise a source of perineal contamination with viable malignant cells and source of local recurrence) [8, 19, 22]. An ellipsoidal incision, 2–3 cm lateral the anal margin, is performed around the anal sphincter; the incision must encompass the entirely external anal sphincter [10, 19, 22]. The dissection starts posteriorly, with the sectioning of the ischiorectal fat, until the levatorian plane is reached; the inferior rectal vessels are ligated or electrocoagulated. Posterior dissection in ischiorectal fossae leads to the discovery of the ano-coccigian ligament, which will be sectioned sharply at the tip of the coccyx, thus entering into the retrorectal space. There is no consensus over the coccyx resection in order to enlarge the dissection space [12]. If the posterior mesorectal dissection was completed in pelvic phase, the two dissections plane will meet at this moment; in case of a bulky posterior tumor, if the posterior mesorectal excision was difficult through the abdomen, the dissection will progress from below, with care to avoid inadvertent perforation of the mesorectal fascia or the tumor. Along with the lateral resection of the levator ani, this is one of the delicate moments of perineal dissection, which could represent a source of local recurrence after APR; therefore, much consideration must be given at this point [2]. Also, care must be taken not to enter the presacral fascia and disrupt the presacral venous plexus.

The dissection continues with the lateral dissection which will permit to enlarge the latero-retrorectal space, by sectioning the levator ani as laterally as possible, close to their origin, and avoiding inadvertent perforation of the tumor, as recommended by Miles himself [4, 12, 14].

When posterior and lateral dissection is finished, the rectosigmoid is extracted through the perineal wound and the anterior dissection commences: less risky in women, in which the report between the anal sphincter and posterior vaginal wall will allow an easier dissection, and a lot riskier in men, due to the vicinity between anal sphincter and male urethra and bladder [19]. Maintaining a good plane is mandatory in order to avoid urinary lesions. After the ano-urethral plane is surpassed, the prostate must be dissected, and then, when the seminal vesicle is reached, the dissection is usually finished and the resection specimen is removed. If an anterior rectal cancer invades (or adheres) to the prostate or the vagina, an en bloc resection will be performed [4] (Figs. 9.4 and 9.5).