Chapter 12 MEASUREMENT OF URINARY SYMPTOMS, HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE, AND OUTCOMES OF TREATMENT FOR URINARY INCONTINENCE

The evaluation of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in women involves several objective and subjective parameters. The difficulty in evaluating treatment outcomes for urinary incontinence is that the objective measures of improvement and cure do not necessarily correlate with the subjective outcomes patients report. This becomes complicated when we consider that the outcomes after surgery for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) include assessment of the surgery (e.g., success, persistent or recurrent SUI); the resolution, persistence, or development of urgency and urge incontinence (UUI); and evaluation of voiding dysfunction. This is an almost overwhelming task, and it remains controversial. Most agree that measuring treatment outcomes requires the collection of objective data to help evaluate the success of treatment and the incidence of complications, as well as subjective patient reports of their outcomes and the influence of post-treatment changes on their health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

To improve the initial evaluation and post-treatment assessment of urinary incontinence, noninvasive outcome measures, including pad tests,1 voiding diaries,2 and questionnaires, have been developed.3,4 A critical addition to the measurement of subjective outcome is the symptom questionnaire.5,6 Although limitations remain in what can be accomplished through the use of a symptom questionnaire, they are clearly more objective than retrospective reviews and can be validated in a systematic fashion. Retrospective chart reviews and the opinions of the surgeons or their surrogates have several limitations, including patient reluctance to complain to surgeons about minor symptoms,7,8 different definitions of success by patients and physicians,9 and potential loss to follow-up of symptomatic patients who seek medical attention elsewhere.7

Although various outcome measures have been proposed, no single tool has met with widespread acceptance. There are no standard definitions of cure or failure, and there are no standardized widely accepted clinical tools to assess outcomes after anti-incontinence surgery. Although attempts to standardize the evaluation of treatment outcomes in urinary incontinence have been made, these recommendations are often not followed. There are no specific recommendations on how to assess patient HRQOL or gather this information.10

HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE

The most common outcome measures for urinary incontinence assess the quantity and frequency of urine loss through voiding diaries, pad tests, or urodynamic testing such as leak point pressure and pressure-flow studies. These observations may confirm the degree of leakage, but they do not reflect the impact of the symptoms on the patients’ quality of life. Norton11 first reported that there was no direct relationship of objective measures of urinary incontinence with the degree of improvement experienced by the patient. Several others have found only weak relationships of the perceived impact of incontinence with measures of frequency and quantity of urine loss.12–15 Consequently, quality-of-life instruments have become an important outcome measure for surgical interventions.16 It is mainly in the past decade that researchers have developed and used several different self-administered questionnaires for urinary incontinence that measure of bother, symptom impact, and HRQOL.

DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF QUESTIONNAIRES

Questionnaires to evaluate LUTS may provide information about the nature of the patient’s problem, the frequency of symptoms, the extent of symptoms, and the impact of symptoms on HRQOL. The ideal questionnaire would help the clinician establish the cause of the problem (i.e., differentiate SUI from UUI) and limit the need for invasive and expensive testing. Questionnaires may include a wide range of items depending on the purpose and target subjects of the study population.

Measurement of Symptoms on Questionnaires

Applying scientific methods to evaluate symptoms that are generated by a great variety of underlying conditions can be complicated. How can the physician be sure that the score from a symptom questionnaire accurately reflects the symptoms the subject reports? Psychometrics is the science of measurement of responses to phenomena that are not easily quantifiable, and the principles of psychometrics govern the development of symptom questionnaires. Symptom scores are only as good as the instrument measuring the symptoms, and psychometric testing provides assurance that symptoms questionnaires measure symptoms.17

Validity

Although urodynamic evaluation is generally accepted as the best available diagnostic test for LUTS, many other standards—history, voiding diary, demonstration of incontinence on examination, and pad testing—have been used for criterion validation of LUTS questionnaires. No one method accurately assesses the scope of LUTS, the severity of the problem, and the cause of LUTS well enough to be the undisputed gold standard.18–21 Nevertheless, results from questionnaires should be compared with several of these objective measures, particularly urodynamic findings, as part of the validation process.

Reliability

Questionnaires that measure the same characteristics should produce similar responses from a subject. The same questionnaire also should produce similar results for a subject over short intervals of time. Reliability is the quantifiable assessment of these sources of error in a questionnaire. Reliability implies the instrument is dependable.17 Internal reliability estimates how the individual items of a questionnaire relate to each other and to the total score. Questionnaires may be divided into two similar tools, each of which may give results similar to each other and to the parent questionnaire. Selected items may be used to construct a short form that is consistent with the original long form of the questionnaire. Cronbach’s α (0-1) indicates the level of internal consistency; values greater that 0.7 are considered acceptable, greater than 0.8 are good, and greater than 0.9 are excellent. Although high internal consistency is desirable, removing redundant items from questionnaires improves clinical speed but diminishes internal consistency. Longer or multiple questionnaires are probably needed for research purposes, but in most clinical situations, we are looking for brevity. Test-retest reliability is evaluated by repeat administration of the questionnaire to subjects over time. Enough time should have elapsed for the subjects to forget their responses to the items, but no change in their symptoms should be evident. A Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficient value of greater that 0.8 indicates high reliability.

The psychometric evaluation of a questionnaire must be evaluated in the context of the study subjects used. Questionnaires may perform very differently after translation to another language or when used in different countries with different races or socioeconomic groups.22 The accuracy of questionnaire data depends on choosing the appropriate tool for the population under study.

The method of data collection can dramatically influence the cure rates reported after anti-incontinence surgery.6,23 Physicians’ biases with the use of retrospective chart review have been repeatedly documented. To eliminate this bias, prospective studies that contain HRQOL assessments have nearly replaced the retrospective chart review. Rodriguez and colleagues24 addressed the question of whether medical personnel (physicians in particular) could reliably fill out HRQOL questionnaires with information obtained from medical interviews? Seventy-nine patients completed the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6) and a quality-of-life survey. An interviewing physician then completed these same instruments based on the interview of the patient. Overall, the physicians underestimated the patient’s degree of bother by 25% to 37%. Self-administered questionnaires minimize bias and are preferred over medical personnel–administered instruments because of labor, time, and cost.

TYPES OF QUESTIONNAIRES

Questionnaires for Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

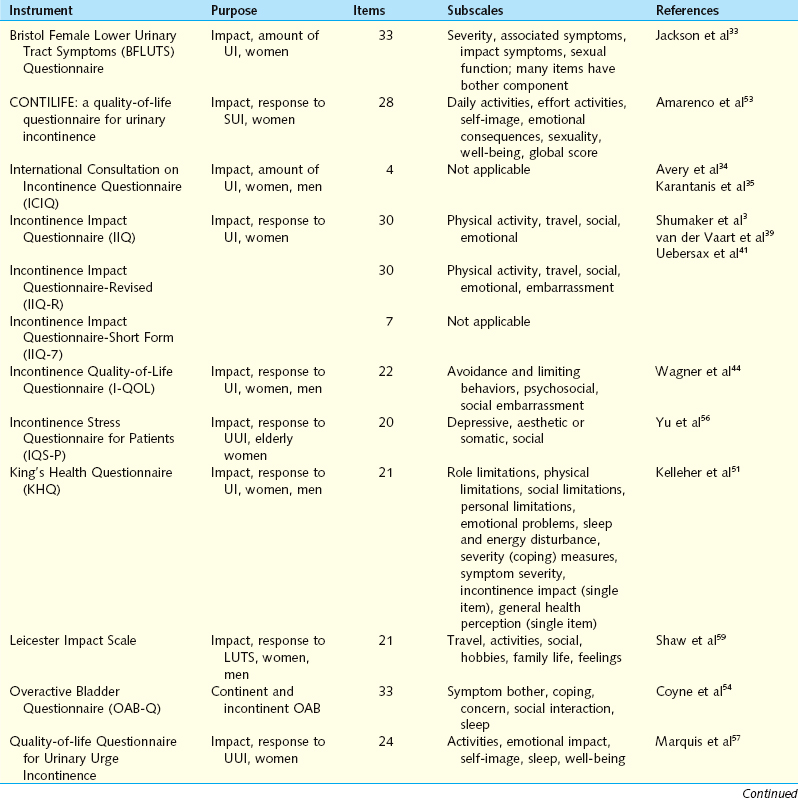

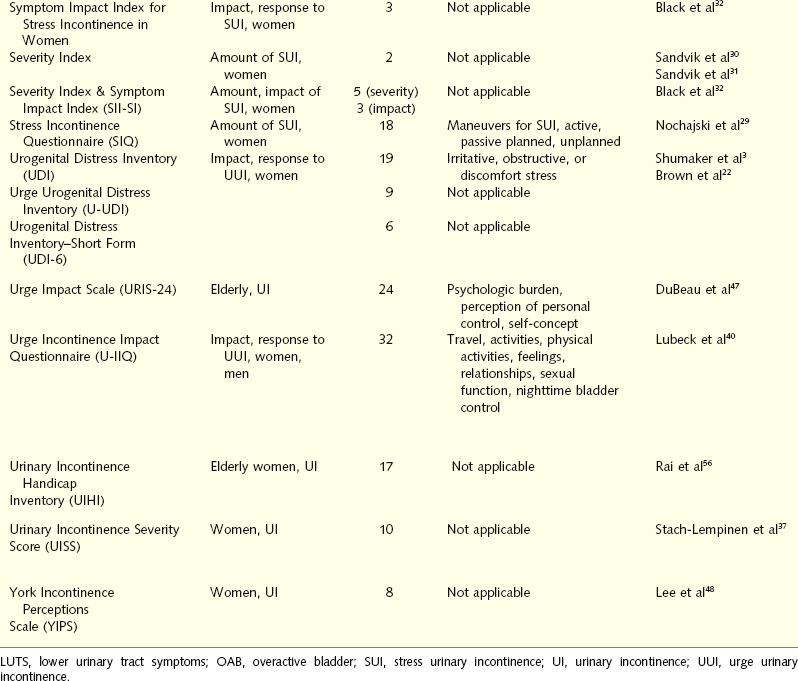

Self-administered symptom questionnaires are designed to accomplish at least one of three objectives: discriminate between SUI and UUI, quantify the amount of symptoms, or assess the impact of symptoms on daily activity and HRQOL. Brief descriptive information and references for each questionnaire are presented in Table 12-1.

Questionnaires for Differentiating Stress Urinary Incontinence from Urgency Urinary Incontinence

The Detrusor Instability Score (DIS) quantifies the extent of detrusor instability symptoms to discriminate stress from urge as the cause for incontinence. The tool is translated from Finnish but has been validated for use in English. DIS scores have been compared with urodynamic findings, demonstrating a low DIS score (0-5) had reasonable predictive value for the absence of detrusor instability. Although sensitivity and specificity are marginal, the DIS has a positive predictive value of 0.82 for determining which patients would not demonstrate detrusor instability on urodynamic evaluation.25,26

The Gaudenz Incontinence Questionnaire has been used widely in Europe as a diagnostic tool to discriminate between SUI and UUI. Initial studies demonstrated high validity. A validation study evaluated the ability of the two subscales to predict urodynamic findings in 1938 women with incontinence. The strict urodynamic criteria used demonstrated detrusor instability in only 2% of women, with 5% having mixed incontinence, making interpretation of this questionnaires performance difficult.27 A shorter, English-language variation of the Gaudenz Incontinence Questionnaire used in Japan was compared with physical examination, pad test, and urodynamic data before and after intervention. Post-treatment scores for both parameters were significantly reduced.28

Questionnaires that Quantify the Amount of Urinary Symptoms

The Stress Incontinence Questionnaire (SIQ) was created to evaluate whether specific activities women routinely perform that result in SUI have diagnostic value. Subjects use a 4-point scale to respond about urinary leakage when performing 18 specific maneuvers. Statistical analysis identified four subscales or factors designated active maneuvers, passive maneuvers, planned maneuvers, and unplanned maneuvers. Psychometric testing using clinical and urodynamic data demonstrated good reliability. The correlation of the four factors with different clinical characteristics suggests that the factors identify different aspects of incontinence.29

The Severity Index attempts to determine the extent that women are bothered by incontinence.30 There are two questions; one asks about the frequency of urinary incontinence, and the second assesses the amount of leakage per urinary incontinence event. The numeric values 1 to 4 for the frequency and 1 to 3 for the amount are multiplied to give the score ranging from 1 to 12. The scores are then divided into four levels of severity. The severity level correlated reasonably well with leakage by 48-hour pad tests, but there was overlap between the severity groups. An updated version includes a very severe category, which identified a subgroup of older women when used in an epidemiologic study. The investigators recommend adding a no leakage response if the questions are being used to monitor outcome.31

Questionnaires that Assess the Amount of Symptoms and the Impact of Symptoms

The Severity Index and the Symptom Impact Index for stress incontinence are paired indices specific for SUI that divide severity and impact into separate scores. The three items of the Symptom Impact Index assess the degree to which women avoid activities because of stress incontinence. After a comprehensive development process, the instrument was found to have good reliability, but convergent validity was demonstrated only through a significant correlation with body mass index. The instrument was not significantly related to the more relevant characteristic of whether a woman had undergone previous surgery for stress incontinence. Conversely, discriminant validity was shown by the lack of correlation between index scores, demographic variables, and unrelated medical history.32

The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Questionnaire (BFLUTS) was developed from the International Continence Society male questionnaire, retaining the same format and many of the items. Thirty-three questions evaluate four domains: incontinence severity, associated symptoms, quality of life, and sexual function. Many of the questions have an additional component assessing the level of associated bother.33 Initial psychometric testing compared BFLUTS scores with voiding diaries and pad tests in 85 incontinent women and control subjects. The frequency of reported symptoms and the degree of bother were significantly higher for all symptoms in the clinical cohort. Criterion validity was confirmed by comparing items assessing urinary frequency and incontinent episodes to the voiding diaries. All voiding diary parameters except daytime frequency correlated well with BFLUTS scores. Subjective assessment of the degree of incontinence correlated with pad test results. Internal consistency and test-retest reliability were confirmed. The BFLUTS questionnaire is a comprehensive tool for evaluating urinary incontinence in women. Its large size may limit general use by clinicians.

The International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) is a four-item questionnaire composed of three scored items and an unscored self-diagnostic item that assesses the prevalence, frequency, and perceived cause of urinary incontinence and its impact on everyday life. It was developed for a wide range of patients for clinical practice and research settings. The ICIQ is easily completed, with low levels of missing data (mean, 1.6%), and it is able to discriminate among different groups of individuals, indicating good construct validity. Convergent validity was acceptable, and reliability was good, with “moderate” to “very good” stability in test-retest analysis and a Cronbach’s α value of 0.95. Statistically significant reductions in symptoms from baseline after surgical and conservative treatment were observed, demonstrating that the ICIQ is responsive.34

The ICIQ, a 24-hour pad test, Stamey grade, and 3-day frequency volume diary used to assess severity were further evaluated in 95 women with primary or recurrent SUI. In the primary SUI group, there was a strong correlation between the ICIQ and the 24-hour pad test results. The ICIQ and 24-hour pad test results also correlated with the mean frequency of urinary loss on the diary but not with the Stamey grade. Although good correlation between the 24-hour pad test and ICIQ in women with primary SUI was demonstrated, no subjective or objective tests correlated for women with recurrent SUI.35 Intraobserver and interobserver reliabilities of the ICIQ have been established by observing that the results obtained from administering the ICIQ at the office or at home were not different from those obtained by the physician during an interview, a potentially unique advantage of this tool.

The ICIQ has been shown to be an effective tool for the assessment of the frequency, severity, and impact on quality of life of urinary incontinence in a wide range of patients. Because it is brief and simple, is responsive to treatment, and includes a measure of quality-of-life impact, the ICIQ may prove to be extremely useful as an outcome measure in patients in clinical and research settings.36

Four of 10 items on the Urinary Incontinence Severity Score assess the amount of leakage, and the other six items refer to the impact of urinary incontinence on a woman’s daily life.37 Although this measure was found to have adequate psychometric properties, the instrument yields only a total score that combines the four symptom items and six symptom impact items. This instrument therefore does not provide a pure indication of symptom impact or quality of life.

Questionnaires that Assess the Impact of Urinary Symptoms

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) and the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) are paired symptom questionnaires that measure the HRQOL effect and the level of distress in women with stress incontinence.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree