Massive Ventral Hernia with Loss of Domain

Alfredo M. Carbonell

Definition of loss of abdominal domain.

There exists no consensus in the literature on the definition of loss of abdominal domain. Determination of this condition is subjective and typically refers to massive hernias with a significant amount of intestinal contents, which have herniated through the abdominal wall into a hernia sac, forming a secondary abdominal cavity.

On physical examination, the inability to reduce the herniated contents below the level of the fascia when the patient is lying supine should raise suspicion of the diagnosis.

Although the surgeon can often make the assumption that a patient has loss of domain on physical examination (Figs. 25.1 and 25.2), we utilize computed tomography (CT) to determine the true nature of the hernia.

Measuring loss of domain

We arbitrarily define a loss of abdominal domain on CT scan as greater than 50% of the intestinal contents lying outside the native abdominal cavity in the hernia sac. This may be more accurately defined when the ratio of the volume of the hernia sac to the volume of the abdominal cavity is ≥0.5.

A sagittal reconstruction of the CT scan is used to measure the length of the hernia sac from the top to the bottom of the sac. The length of the abdominal cavity is measured from the top of the diaphragm to the top of the symphysis pubis (Fig. 25.3).

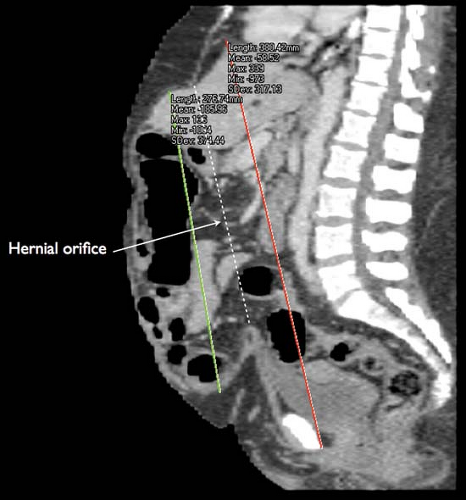

Axial reconstructions are used to measure the width of the hernia sac and abdominal cavity at their widest point. The height of the hernia sac is measured from an imaginary line drawn across the hernial orifice to the apex of the hernia sac at its tallest portion. The height of the abdominal cavity is measured from the anterior portion of the fourth lumbar space to an imaginary line drawn across the hernial orifice (Fig. 25.4).

Using the formula to measure the volume of an ellipsoid (V = 4/3 × π × r1 × r2 × r3), the hernia sac and abdominal cavity volumes can be measured and compared.

To simplify the ellipsoid volume equation, multiply the length, height, and width measurements of the cavities times a factor of 0.52 (V = 0.52 × L × H × W). Loss of domain exists when the ratio of the volume of the hernia sac to the volume of the abdominal cavity is ≥0.5.

Physiology of hernias with loss of abdominal domain

In patients with loss of abdominal domain the bowels reside outside the abdominal cavity. As intraabdominal pressure decreases to approach atmospheric pressure, abdominal viscera become edematous and their vasculature become engorged. This makes simple hernia reduction near impossible.

Respiratory function is altered secondary to the loss of diaphragmatic support, and anterior spinal support fails leading to lordosis.

The difficulty in repair of these hernias is that, not only are the herniated contents difficult to relocate back into the abdominal cavity, but doing so abruptly may result in postoperative physiologic collapse due to the creation of abdominal compartment syndrome.

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction Techniques

Reconstruction techniques for hernias with loss of domain must focus first upon the ability to relocate the herniated contents back into the native abdominal cavity and secondly, the ability to re-approximate the midline fascia overtop a retromuscular-implanted prosthetic mesh.

To re-accommodate such a large volume of herniated contents, the surgeon must employ a modality which increases the volume of the abdominal cavity. This can only occur by lengthening the abdominal wall musculature via either:

Mechanical traction

Anatomic alteration

Synthetic replacement

Combination of techniques

Mechanical Traction

Progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum

Insufflation of the peritoneal cavity acts as an intraperitoneal pneumatic tissue expander and lengthens the abdominal wall musculature, increasing the volume of the abdominal cavity. This allows for adequate accommodation for the herniated contents and is our preferred preparatory technique.

It also attenuates the adverse physiologic effects associated with ventral hernia repair in patients with a loss of abdominal domain, by slowly creating a chronic abdominal compartment syndrome. With decreased diaphragmatic excursion,

the patient is forced to overcome the inherent decreased inspiratory capacity. In addition, the adverse cardiovascular effects of acute abdominal compartment syndrome are attenuated by the slow introduction of intraperitoneal air.

Laparostomy with progressive mesh excision

This technique employs a synthetic mesh sewn to the edges of the hernia defect as an inlay. Over multiple successive operations, a central portion of the mesh is excised, and the mesh re-sutured in the midline. This provides a slow and progressive mechanical traction on the midline fascia, allowing for eventual fascial re-approximation. Although effective, this technique is cumbersome, and requires multiple operations.

Tissue expanders

Synthetic tissue expanders can be placed between abdominal wall muscle layers and slowly expanded over the course of several weeks. The expander balloon lengthens the abdominal muscles by exerting a mechanical traction. We prefer this technique for skin expansion alone, when there is a concern over potential inadequate skin coverage during hernia repair.

Anatomic Alteration

Component separation

This technique provides an increase in abdominal circumference with the possibility of subsequent fascial closure by disconnecting musculofascial layers, which lengthen the overall abdominal wall musculature. We employ a unique posterior component separation technique with retromuscular mesh reinforcement of the abdominal wall reconstruction.

Synthetic Replacement

Silo technique

This technique is utilized for hernia defects so wide that no preparatory techniques or intraoperative maneuvers available would allow for native fascial re-approximation. These hernias require that a synthetic mesh span the entire defect and contain the herniated intestines like a silo, similar to the technique used for treatment of congenital abdominal wall deformities such as omphalocele and gastroschisis. The only difference here, being that the prosthetic is left in situ with skin and subcutaneous coverage alone. This is the least desirable of all the techniques; however, it may be the only option in select patients.

Physical examination

The physical examination alone is often helpful in determining whether a patient has loss of domain. With the patient lying supine on the examination table, the surgeon should attempt to reduce the herniated contents below the fascia. If the hernia does not reduce due to the amount of herniated contents, the patient likely has a component of loss of domain.

The abdominal wall should be examined for elasticity. Although some massive hernias may be irreducible, the patient’s abdominal wall musculature may have such elasticity so as to accommodate the herniated contents easily at the time of surgery. This finding would obviate the need for any preparatory procedures such as progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum, since a single stage repair may be feasible.

The quality of the skin should be examined to determine if any adjunctive maneuvers will be required to obtain safe skin closure at the time of hernia repair.

Widened thin scars, skin ulceration, thin subcutaneous tissue with tense and immobile skin, and large pannus flaps should all raise concern over skin closure. Consultation with a plastic surgeon may help to determine the need for preoperative tissue expanders, panniculectomy, or complex skin closure at the time of hernia repair.

Computed tomography (CT)

As previously described, the volume of the hernia sac and abdominal cavity are calculated and compared. A volume ratio of the hernia sac to the abdominal cavity of ≥0.5 confirms loss of abdominal domain.

Other attributes of the abdominal wall should be examined on CT as they may help determine which adjunctive maneuvers will be required for hernia repair.

In our experience, patients with smaller defects and a significant amount of herniated contents benefit the most from progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum.

Patients with round-shaped abdominal cavities on axial imaging and thick, robust rectus abdominis and oblique muscles may experience less muscle lengthening with preoperative pneumoperitoneum compared to those with a more ellipsoid appearance to the abdominal wall and thin atrophic musculature.

Patients with “open book” abdomens such as those with significant loss of abdominal wall substance (missing abdominal wall musculature) and hernia defects which span the entire abdominal wall may not benefit anatomically from preoperative pneumoperitoneum as there may not be enough abdominal wall musculature to stretch. The physiologic benefits may still be realized, however. These patients may be best served by the silo technique.

Perioperative analgesia

Strong consideration should be given to the use of epidural anesthesia in the postoperative arena.

The cardiac and pulmonary benefits of epidural anesthesia have been proven and in these patients, preservation of pulmonary function is often critical to their recovery.

Our preferred approach to hernias with loss of domain is progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum, to prepare patients both physiologically and anatomically for the repair.

This is followed by the posterior component separation technique with retromuscular mesh placement.

We will also discuss the laparostomy with serial mesh excision technique as well as the silo technique.

Progressive Preoperative Pneumoperitoneum and Posterior Component Separation Technique

Stage I

Placement of percutaneous vena cava filter

Progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum significantly elevates the intraabdominal pressure and creates a chronic abdominal compartment syndrome. As a result, there will be decreased venous return through the vena cava and patients are at risk for thromboembolic events.

Percutaneous vena cava filters protect patients from life-threatening pulmonary emboli. They do not, however, prevent deep venous thrombosis.

We place patients on thrombotic chemoprophylaxis with heparin sodium.

Despite these aggressive measures, we have still had patients develop significant deep venous thrombosis and near caval occlusion. Full dose anticoagulation may be indicated in the more at-risk patients.

Exploratory laparoscopy with placement of percutaneous catheter system

Exploratory laparoscopy allows for minimally invasive access to the abdominal cavity for direct visualization and placement of a percutaneously placed intraperitoneal catheter system for the pneumoperitoneum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree