Chapter 60 MANAGEMENT OF THE URETHRA IN VAGINAL PROLAPSE

One of the greatest challenges to the reconstructive pelvic floor surgeon is the approach to pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in the clinically continent woman. It is controversial whether the urethra should be surgically addressed at the time of vaginal prolapse repair. It has been proposed that a prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure be performed concomitantly due to the risk of developing stress urinary incontinence (SUI) once the vaginal axis has been restored. The counterargument suggests that, because only a small percentage of continent women with POP develop SUI postoperatively, many patients would undergo an unnecessary procedure with this approach. Even the most minimally invasive anti-incontinence procedures carry a potential risk of morbidity to the patient.

EFFECT OF PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE ON URINARY SYMPTOMS

Moderate and severe pelvic floor relaxation can present with a variety of lower urinary tract symptoms. Many urinary symptoms can be attributed to obstructive voiding. These symptoms may include frequency, urgency, nocturia, hesitancy, double-voiding, sense of inadequate emptying, stranguria, flow intermittency, and suprapubic discomfort. Elevated postvoid residual volumes can also lead to recurrent or persistent urinary tract infections. Hypothetical causes include urethral kinking, urethral compression, bladder neck elongation, and detrusor hypocontractility/dysfunction. When severe prolapse involves the bladder, patients can also present with ureteral obstruction and hydronephrosis.1,2

Patients with POP may be continent or incontinent. Mechanisms for continence in prolapse include urethral obstruction, anatomic urethral kinking with descent of the bladder base, and abdominal pressure dissipation.3 These mechanisms may also contribute to obstructive voiding symptoms. Bergman and colleagues4 proposed that, in prolapse, a large cystocele provides a “cushion effect” that absorbs some of the intraabdominal pressure, effectively lowering the abdominal pressure placed on the continence mechanism (urethral complex). Ghoniem and associates3 proposed that the only fixed portion of the lower urinary tract in large cystoceles is the distal urethra, supported by the pubourethral ligament. They hypothesized that the pubourethral ligament may be the only supporting structure that maintains its strength in the setting of severe prolapse, allowing for urinary continence.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Dietz and coworkers5 reported on 223 vaginal prolapse patients with symptoms of lower urinary tract symptoms presenting in two urogynecology clinics. Urinary symptoms included SUI in 64% (142 patients), urge incontinence in 61% (134), frequency in 38% (84), nocturia in 38% (84), and obstructive symptoms (including stranguria, sense of incomplete emptying, intermittency, and hesitancy) in 56% (124).

Cystocele

Romanzi and colleagues6 prospectively evaluated 60 women with various degrees of cystocele and found the following urinary complaints (patients could have more than one symptom): frequency/urgency, 35%; urge incontinence, 15%; stress incontinence, 60%; and difficult voiding 23%. Women with higher stages of anterior prolapse had a statistically greater likelihood of obstructive voiding than did those with lower stages of prolapse (70% in grades 3/4 versus 3% in grades 1/2). Obstruction was defined as a maximum detrusor pressure at maximum flow (PdetQmax) of greater than 25 cm H2O and a maximum flow of less than 15 mL/sec.

Uterovaginal Prolapse

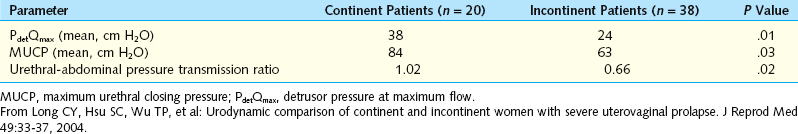

Patients with uterovaginal prolapse may also present with lower urinary tract symptoms. The group at Kaohsiung Medical University7 studied 38 clinically continent and 20 incontinent women with stage III/IV complete uterovaginal prolapse. Incontinent women were more likely to report urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. However, the continent women had a higher incidence of voiding hesitancy. Urodynamic parameters between the two groups were compared. The women without stress incontinence had significantly higher (PdetQmax), maximum urethral closure pressures (MUCP), and urethral-abdominal pressure transmission ratios (Table 60-1). The pressure transmission ratio should be 1.0 (ideal) when increases in abdominal pressure are transmitted equally to the abdominal transducer (usually rectal or vaginal) and the urethral transducer. With rotation of the urethra, compressive forces from the abdominal cavity are incompletely transmitted to the urethral complex, creating a ratio of less than 1.0.

Posthysterectomy Vault Prolapse and Enterocele

Wall and Hewitt8 described urinary characteristics in 19 women with complete posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. Symptoms of urgency was present in 79% (15 patients) and urge incontinence in 63% (12 patients). Occult SUI was demonstrated by prolapse reduction with a single-bladed speculum in 47% (9 patients). Urodynamic parameters included peak flow rate (Qmax) and PdetQmax. The mean Qmax was 11 mL/sec, and PdetQmax was 50 cm H2O, meeting the pressure-flow parameters for female outlet obstruction outlined by Massey and Abrams.9

Rectocele

Even patients with isolated posterior wall support defects can have masked SUI. Myers and colleagues10 evaluated 90 patients with isolated posterior compartment prolapse, including 28 with grade III+ rectoceles. Fourteen percent (n = 4/28) demonstrated SUI when their prolapse was reduced with a split Pederson speculum that was not present without prolapse reduction. The mean decrease in MUCP with rectocele reduction was 7.0 cm H2O. The authors theorized that severe posterior wall defects act to compress and support the anterior wall, artificially raising the MUCP, increasing functional length, and masking SUI.

Women with POP can present with a myriad of urinary symptoms. A thorough history must include extensive details of voiding habits, including a previous history of incontinence that improved with worsening prolapse. As with staging of prolapse severity, physical examination findings can vary with bladder volume, rectal contents, and position. The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network recently published their findings on technique modifications that can result in intraobserver variability.11 Prolapse was graded as more severe in the standing position compared with the lithotomy supine position. The type of speculum was not standardized. Prolapse severity was consistent using either a split speculum or a manual (two-digit) reduction method. Urinalysis should be performed to rule out urinary tract infection, and a culture with sensitivities can be sent if necessary. A screening postvoid residual volume measurement, either by catheterization or by bladder ultrasound, is a simple means to identify patients with urinary retention.

OCCULT STRESS INCONTINENCE IN PROLAPSE

Many patients with significant POP are continent and demonstrate SUI only when their prolapse is reduced. There is no “gold standard” method for determining whether a patient has occult SUI. The incidence of “masked” incontinence varies with the method of prolapse reduction, with rates of 25% to 80% reported in the literature.12–15

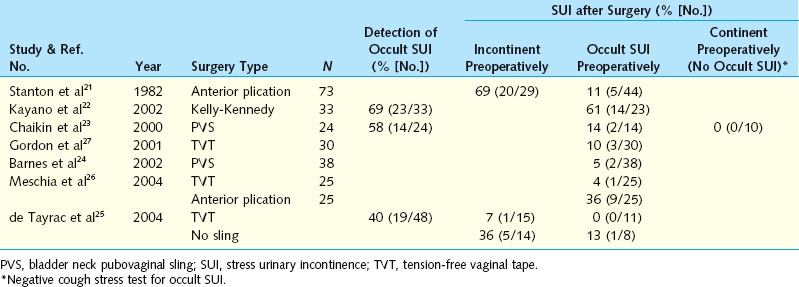

The goal of prolapse reduction is to simulate surgical repair and determine whether the patient will be at risk for development of postoperative de novo SUI. Potential pitfalls include obstructing the urethra, which would lower the SUI detection rate, and mechanically widening the levator hiatus, which would falsely elevate the SUI detection rate (Table 60-2).

Table 60-2 Detection Rate of Occult SUI after Anti-incontinence Surgery According to Preoperative Status

Pessary

The primary objective of a pessary is to reduce symptomatic vaginal prolapse. A pessary can be used temporarily to assess for underlying SUI, as described later. Patient satisfaction is also high when these devices are used for nonoperative management of prolapse. Clemons and associates16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree