Increasing use of antiplatelet therapies is associated with increasing GI complications, such as ulceration and GI bleeding. Identification of high-risk patients and, in such patients, incorporation of strategies to reduce their GI risk would be clinically prudent. After assessment and treatment of H pylori in patients with prior ulcer or GI bleeding histories, further reduction in GI risk in other high-risk patients who require antiplatelet agents is primarily accomplished by prescribing drugs that when coadministered with antiplatelet agents protect against mucosal ulceration, primarily proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). However, observational studies indicate a higher cardiovascular event rate in patients taking PPIs along with clopidogrel and aspirin compared with that of patients undergoing dual antiplatelet therapy without PPIs. Whether concurrent use of a PPI with clopidogrel represents a safety concern or not is currently being evaluated by the US Food and Drug Administration. Until more specific regulatory guidance is available, current recommendations are that patients taking both PPIs and clopidogrel concurrently should probably continue to do so until more data become available.

In treating cardiovascular disease, clinicians are commonly caught between competing considerations of cardiovascular benefit and gastrointestinal (GI) risks. Because platelets have an important role in the pathophysiology of coronary artery and coronary stent thrombosis, drugs that prevent platelet thrombosis have acquired a critical role in the prevention of atherothrombotic complications of vascular disease. In recent years, the use of antiplatelet therapies has been markedly increasing, primarily for the prevention of coronary artery and coronary stent occlusion. Additionally, in the prevention of cerebrovascular occlusion, antiplatelet therapies are among the principal treatments. As evidence accumulates regarding the benefits of antiplatelet therapies in the treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, the use of these agents in clinical practice continues to increase even more.

Currently, two categories of oral antiplatelet therapies, aspirin and the thienopyridines (clopidogrel and prasugrel), are available or are under clinical development for the prevention of atherothrombotic complications in patients with the acute coronary syndrome or who are undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Although the evidence is clear from several well-designed trials that antiplatelet therapies have clinical benefit, the increasing use of these agents in clinical practice is associated with increasing GI complications, such as ulceration and GI bleeding. Because of the increasing rates of ulcer and GI complications being encountered with these drugs, this article focuses on management strategies that may reduce the GI risks of patients who take antiplatelet therapy, especially those patients at highest risk for development of a GI event while using these antiplatelet agents.

Mechanisms of Gastrointestinal injury with antiplatelet therapies

Aspirin reduces platelet activity by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes. Although aspirin can inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 isoenzymes, the platelet primarily comprises COX-1. Aspirin permanently inhibits platelet COX-1 at relatively low dosages, resulting in inhibition of platelet activity. COX-2–mediated effects of aspirin, primarily the analgesic and anti-inflammatory consequences, are inhibited at higher aspirin dosages. Aspirin irreversibly inhibits the metabolism of arachidonic acid to thromboxane A 2 (TXA 2 ), which is highly sensitive to aspirin’s effects, causing complete suppression of platelet TXA 2 production with a few doses of aspirin. This inhibition of TXA 2 decreases platelet aggregation, causes vasodilation, reduces the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, and decreases atherogenicity.

In the GI mucosa, the principal metabolic products of COX enzymes are the prostaglandins, substances that protect against GI mucosal injury. In the presence of a COX inhibitor, such as aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), GI COX is inhibited, which results in increased degrees of GI mucosal injury. At daily aspirin dosages that are much lower than that desired for optimal cardiovascular efficacy, such as with 10 mg aspirin per day, gastric COX is markedly inhibited, mucosal prostaglandins are reduced to 60% of baseline, and GI ulceration occurs. Therefore, there is likely no dose of daily administered aspirin that is therapeutically efficacious without conferring gastric mucosal injury.

Clopidogrel is an effective antithrombotic, because it blocks platelet activation of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) by irreversibly binding to platelets’ ADP receptor, thereby preventing the ADP-dependent activation of the GpIIb-IIIa complex, the primary platelet receptor for fibrinogen. In the CAPRIE trial, a randomized trial comparing clopidogrel and aspirin for the prevention of ischemic events, a randomized, prospective study of the efficacy of clopidogrel 75 mg and aspirin 325 mg daily for secondary prevention of thrombotic vascular events, clopidogrel was marginally more effective than aspirin and resulted in modestly lower GI bleeding than aspirin (0.5% vs 0.7%). In short-term endoscopic evaluations of healthy volunteers, clopidogrel causes less gastroduodenal damage than aspirin 325 mg daily, and, in observational trials of populations undergoing antiplatelet therapies, clopidogrel has a nonsignificant, slightly lower rate of GI bleeding than that with aspirin. Despite this reduction, the GI risks of thienopyridines are not zero. In fact, the use of prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes with scheduled PCI is associated with significantly reduced rates of cardiovascular ischemic events when compared with those with clopidogrel. However, prasugrel’s increased cardiovascular efficacy is somewhat offset by an increased risk of major GI bleeding, including fatal bleeding. Furthermore, the use of thienopyridines in high GI risk patients can result in high rates of GI bleeding. In patients with a prior history of GI bleeding, recurrent GI bleeding after only 1 year of clopidogrel can be observed in as high as 9% of patients taking this agent. These observations indicate that, although it may have previously been assumed that the thienopyridines were the GI-safe alternatives to aspirin, these agents in fact are associated with considerable GI risks as well.

The mechanism that underlies the GI injury of thienopyridines is currently unclear. However, it has been hypothesized that agents such as clopidogrel and prasugrel may cause their GI injury through an impairment of ulcer healing. Platelet aggregation plays a critical role in ulcer healing through the release of various platelet-derived growth factors that promote angiogenesis, which is essential for ulcer healing. For example, thrombocytopenic animals have reduced ulcer angiogenesis and impaired gastric ulcer healing. ADP receptor antagonists impair gastric ulcer healing by inhibiting platelet release of proangiogenic growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes endothelial proliferation and accelerates ulcer healing. Interestingly, new chemotherapeutic agents comprising monoclonal antibodies directed at circulating VEGF have GI bleeding as a major clinical toxicity. Impairment of platelet activity has also been suggested in endoscopic studies to contribute to the mechanism of clinical GI bleeding associated with clopidogrel. Although clopidogrel and other agents that impair angiogenesis might not be primarily responsible for GI ulcer induction, their antiangiogenic effects may impair healing of background ulcers, which, when combined with their propensity to increase bleeding, may convert small, silent ulcers into large ulcers that bleed profoundly.

Magnitude of gastrointestinal ulceration complications with antiplatelet therapies

Aspirin

Estimates of the incidence of GI complications with cardioprotective doses of aspirin come from several prospectively conducted studies of patients taking low-dose aspirin for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular events. Although the point estimate of the incidence of GI events with aspirin varies across the prospective trials, meta-analyses of these studies indicate that the relative risk (RR) of a GI event in a patient taking low-dose aspirin increases by 1.5- to 3.2-fold when compared with that of non–aspirin-taking individuals. However, the absolute risk of aspirin’s clinical risks on an individual basis are small and are estimated to range from one to five out of 1000 exposed patients. On the other hand, when these data are viewed from a population perspective, the population impact of the GI adverse effects of low-dose aspirin is likely substantial when considering that it has been estimated that 50% of adults aged 20 to 80 years in the United States are candidates for low-dose aspirin. Furthermore, the excess risk attributable to aspirin will vary in parallel to the underlying GI risk of a patient. In a patient with a combination of risk factors, such as age more than 70 years and past history of ulcer complication, the attributable risk is increased to more than 10 extra cases per 1000 person years.

Clopidogrel

In the CAPRIE trial, clopidogrel had modestly lower rates of GI bleeding compared with those with aspirin (0.5% vs 0.7%, respectively), Extrapolating from that trial, substituting clopidogrel for aspirin in 1000 patients would result in a reduction of two patients with GI bleeding. In patients at high risk for GI bleeding, rates of GI bleeding on clopidogrel will be considerably higher. In clinical practice, however, clopidogrel is rarely given as a stand-alone antiplatelet therapy, and the dual antiplatelet strategy of clopidogrel plus aspirin is a much more commonly encountered combination. Thus, rates of GI events with dual antiplatelet therapy better reflect clopidogrel’s actual GI effects in clinical practice.

Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

In patients who are at high risk for development of coronary occlusion, such as those with drug-eluting coronary stents, at least 1 year of dual antiplatelet therapy is currently recommended. In clinical trials comparing the dual antiplatelet strategy of clopidogrel plus aspirin to aspirin therapy alone, the dual antiplatelet strategy is associated with an approximate 2-fold greater incidence of GI complications when compared with either agent alone Observational studies indicate a seven-fold increase in upper GI bleeding with the combination therapy when compared with aspirin, with GI risk increasing in patients who are at higher risk. Clearly, in certain patients dual antiplatelet therapy can be a strategy associated with considerable risks of GI bleeding. Therefore, identification of high-risk patients and, in such patients, incorporation of strategies to reduce their GI risk would be clinically prudent.

Magnitude of gastrointestinal ulceration complications with antiplatelet therapies

Aspirin

Estimates of the incidence of GI complications with cardioprotective doses of aspirin come from several prospectively conducted studies of patients taking low-dose aspirin for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular events. Although the point estimate of the incidence of GI events with aspirin varies across the prospective trials, meta-analyses of these studies indicate that the relative risk (RR) of a GI event in a patient taking low-dose aspirin increases by 1.5- to 3.2-fold when compared with that of non–aspirin-taking individuals. However, the absolute risk of aspirin’s clinical risks on an individual basis are small and are estimated to range from one to five out of 1000 exposed patients. On the other hand, when these data are viewed from a population perspective, the population impact of the GI adverse effects of low-dose aspirin is likely substantial when considering that it has been estimated that 50% of adults aged 20 to 80 years in the United States are candidates for low-dose aspirin. Furthermore, the excess risk attributable to aspirin will vary in parallel to the underlying GI risk of a patient. In a patient with a combination of risk factors, such as age more than 70 years and past history of ulcer complication, the attributable risk is increased to more than 10 extra cases per 1000 person years.

Clopidogrel

In the CAPRIE trial, clopidogrel had modestly lower rates of GI bleeding compared with those with aspirin (0.5% vs 0.7%, respectively), Extrapolating from that trial, substituting clopidogrel for aspirin in 1000 patients would result in a reduction of two patients with GI bleeding. In patients at high risk for GI bleeding, rates of GI bleeding on clopidogrel will be considerably higher. In clinical practice, however, clopidogrel is rarely given as a stand-alone antiplatelet therapy, and the dual antiplatelet strategy of clopidogrel plus aspirin is a much more commonly encountered combination. Thus, rates of GI events with dual antiplatelet therapy better reflect clopidogrel’s actual GI effects in clinical practice.

Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

In patients who are at high risk for development of coronary occlusion, such as those with drug-eluting coronary stents, at least 1 year of dual antiplatelet therapy is currently recommended. In clinical trials comparing the dual antiplatelet strategy of clopidogrel plus aspirin to aspirin therapy alone, the dual antiplatelet strategy is associated with an approximate 2-fold greater incidence of GI complications when compared with either agent alone Observational studies indicate a seven-fold increase in upper GI bleeding with the combination therapy when compared with aspirin, with GI risk increasing in patients who are at higher risk. Clearly, in certain patients dual antiplatelet therapy can be a strategy associated with considerable risks of GI bleeding. Therefore, identification of high-risk patients and, in such patients, incorporation of strategies to reduce their GI risk would be clinically prudent.

Patients at risk for ulcers and Gastrointestinal complications while on antiplatelet therapies

Across all therapeutic categories, strategies aimed at reducing GI risks should ideally target patients most at risk for the development of complications. With the antiplatelet therapies, there has not been as much work done in the identification of patients at greatest risk of developing GI complications as with other categories of medications such as the NSAIDs. However, because of several large-scale clinical trials that have been conducted in the evaluation of efficacy of aspirin and the thienopyridines, there are sufficient emerging data to suggest which groups constitute the highest GI risk patients among those undergoing antiplatelet therapies ( Table 1 ).

| Aspirin | Clopidogrel |

|---|---|

| Prior ulcer complication | Prior ulcer complication |

| Prior ulcer disease | Combination of clopidogrel with NSAID |

| Advanced age | Combination of clopidogrel with aspirin |

| H pylori | Combination of clopidogrel with anticoagulant |

| Dose of cardioprotective aspirin | |

| Combination of aspirin with NSAID | |

| Combination of aspirin with anticoagulant | |

a Risk factors were compiled from data presented in several studies; References.

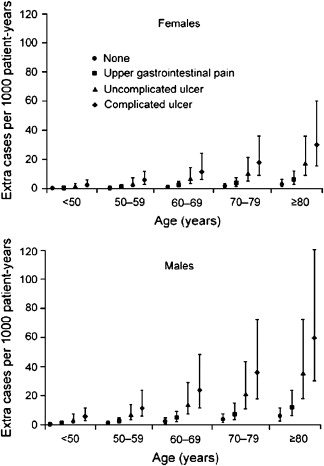

Aspirin

Among aspirin-taking patients, analyses of large patient care databases in the United Kingdom and Spain indicate that patients taking aspirin with advancing age, a past history of uncomplicated ulcer, and a past history of complicated ulcer are all at increased risk for the development of an ulcer ( Fig. 1 ). The most significant risk factor for an aspirin-induced complication is a history of prior complicated ulcer disease, as 15% of patients with a prior history of bleeding ulcer who are taking aspirin at a dose of 100 mg/d will have a recurrent bleeding ulcer at 1 year. Advancing age is also a risk factor. Although there does not appear to be a threshold age at which the risk dramatically increases, the risk increases linearly at the rate of approximately 1% per decade of advancing age.

Helicobacter pylori ( H pylori ) infection is also a risk factor for the development of ulcers and of ulcer complications in patients taking low-dose aspirin. In endoscopic studies of aspirin users, H pylori -infected patients aged 60 years or older who received low-dose aspirin were more likely to develop duodenal ulcers than aspirin-taking patients without the infection. In a case-control study of low-dose aspirin users, H pylori increased the risk of upper GI bleeding five-fold when compared with noninfected patients with upper GI bleeding. It is clear that H pylori increases risk of ulcers related to low-dose aspirin. However, the data have not been as straightforward as to whether eradication of H pylori before starting aspirin will reduce future ulcer risk in patients with a history of ulcer. In a 6-month randomized trial of H pylori eradication that compared maintenance therapy with omeprazole in aspirin users with H pylori infection and a bleeding ulcer history, rates of recurrent ulcer bleeding were comparable among the two treatment groups, suggesting that H pylori eradication alone may reduce ulcer risk with low-dose aspirin to the level obtained with proton pump inhibitor (PPI) cotherapy. In another prospective, randomized study, all low-dose aspirin users with H pylori infection and a history of ulcer bleeding were treated for H pylori before being randomized to a PPI or placebo. One year later, rates of recurrent bleeding were significantly nine times higher in those who had received eradication therapy alone, suggesting that treatment for H pylori alone in high-risk users of low-dose aspirin may be insufficient to reduce their subsequent bleeding risks. However, in this study two-thirds of the patients with recurrent ulcer bleeding who had received H pylori treatment had persistent H pylori infection after treatment or were concomitantly taking NSAIDs. Thus, recurrent bleeding in patients in this study reflected failure to eliminate the H pylori infection rather than failure of effective eradication to reduce subsequent aspirin-related GI bleeding. In a more recent and larger prospective trial, patients with a prior history of bleeding ulcer who were infected with H pylori, but who also had confirmation of successful H pylori eradication before starting low-dose aspirin, had very low (∼1%) rates of recurrent bleeding ulcers in up to 4 years of follow-up without concomitant PPI therapy. Therefore, a reasonable conclusion from these studies regarding the contribution by H pylori to the risk of aspirin-related GI bleeding is that confirmed eradication of H pylori results in considerable reductions in risk of recurrent bleeding in high GI risk patients who take aspirin.

The dose of aspirin also appears to be related to GI ulcer risk, as a higher range of low-dose aspirin, between 100 and 325 mg/d, contributes to an increased risk of gastric or duodenal ulcer. Although meta-analyses of the risk of aspirin dose and GI bleeding certainly suggest a trend in favor of lower doses of aspirin being associated with reduced GI risk, no study has been able to prove that 81 mg of aspirin daily is associated with statically fewer GI complications than 325 mg of aspirin per day. It has also been suggested that modifications to the formulation of aspirin might be associated with a lower GI bleeding risk. However, when enteric-coated and buffered aspirin formulations were compared with plain aspirin for their risks of major GI bleeding, GI risks were not lowered by the modified formulations of aspirin.

Concurrent use of low-dose aspirin with an NSAID is also a risk factor for GI ulcer complications. Observational studies have noted that, compared with the risk of low-dose aspirin taken alone, when low-dose aspirin is combined with an NSAID, the RR of upper GI complications increases by two- to four-fold. In certain clinical scenarios, patients achieve cardiovascular benefit from the addition of anticoagulants, such as heparin or coumadin, to low-dose aspirin. However, the addition of heparin or coumadin to low-dose aspirin may increase risks of major bleeding by 50% to two-fold, respectively.

Clopidogrel

Similar to observations with low-dose aspirin, in patients taking clopidogrel as the sole antiplatelet therapy, a prior history of bleeding has been observed in several studies to be a risk factor that places these patients at substantial risk for GI complications on clopidogrel. In a retrospective cohort analysis of patients taking clopidogrel, 22% of patients with a prior history of GI bleeding had recurrent GI bleeding while taking clopidogrel, whereas no patients without a prior history of GI bleeding had bleeding while on this antiplatelet agent. Prospectively conducted trials of patients with prior histories of ulcers have demonstrated rates of recurrent GI bleeding ranging from 9% to 13% of patients by 1 year.

Concomitant use of clopidogrel with an NSAID has also been suggested by observational studies to increase the GI risks of clopidogrel. In one observational study, concurrent use of clopidogrel with an NSAID increased the RR of upper GI bleeding by 15.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.1–56.5). A substantial increase in GI bleeding risk is also conferred by the combined used of clopidogrel, anticoagulants, and aspirin. Studies of clopidogrel have not yet reported the effects of advancing age or H pylori on clopidogrel’s GI risks. However, since all other risk factors studied with clopidogrel have shown consistent similarity to GI risk factors with aspirin, for now it would be prudent to assume that these other as of yet unstudied GI risk factors with clopidogrel are similar to those seen with aspirin. Furthermore, any risk factor demonstrated in association with either of the individual antiplatelet therapies should be similarly assumed to be associated with GI risk with combination antiplatelet therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree