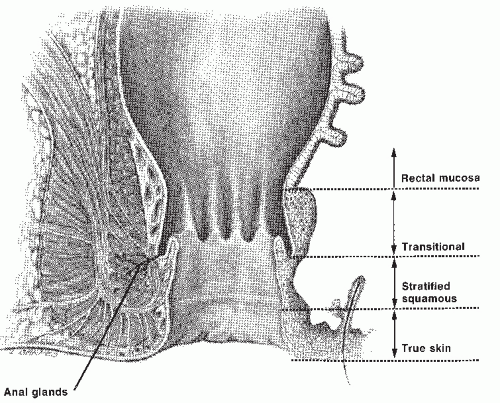

However, some authors place the dentate line at the proximal limit of the anal canal, at the junction between the rectal mucosa and transitional zone.60,78 The more distal zone of the anal canal is lined by stratified squamous epithelium and can be differentiated histologically from perianal skin by the absence of the epidermal appendages found in the skin. Thus, a finger examining the anal canal first passes the perianal skin, the squamous epithelium of the distal anal canal, the transition zone, and finally reaches the rectal mucosa. Separating tumors that arise in the anal canal from those of the perianal skin is important because their biologic behavior and, consequently, the treatments are distinctly different.

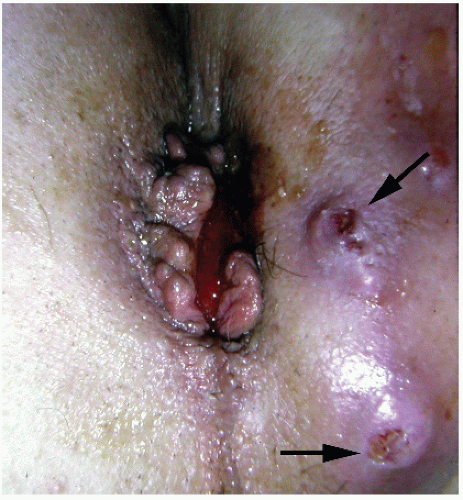

perianal skin (Figure 25-4).119 Management of these conditions is discussed in Chapter 9. Carcinomas of the anal margin have a better prognosis than that of tumors of the anal canal. Mendenhall and colleagues reviewed the experience at the University of Florida, Gainesville, of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal margin.95 They concluded that superficial, well to moderately differentiated T1 cancers of the anal margin may be successfully treated with radiotherapy alone or by local excision. However, because stage T2 lesions have an increased risk for lymph node metastases to the groin, they recommended radiotherapy to the primary tumor in conjunction with elective inguinal lymph node radiation. Concurrent chemotherapy may also be prudent for T2 or greater tumors.5 Abdominoperineal resection (APR) is reserved for those who have complications secondary to the radiation therapy or locally recurrent disease.5,95 Greenall and coworkers reported the results of treatment of 48 patients with anal margin lesions.57 Local excision was associated with a corrected 5-year survival rate of 88%, but 46% of these individuals developed a local or regional recurrence. Additional treatment contributed to the satisfactory results, but APR did not improve survival.

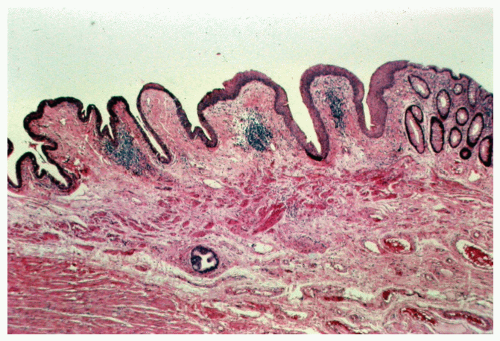

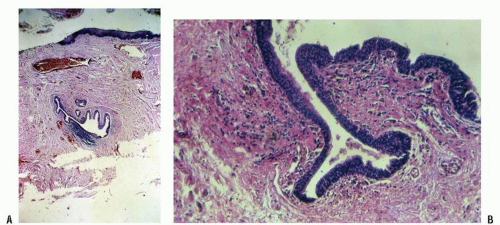

FIGURE 25-3. Cross section of a normal gland (A) and an anal duct (B). (Original magnification × 250; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

metastasize (see Figure 9-75). The defect created by excision can be left to granulate, covered by a split-thickness skin graft or, in some instances, may be closed by rotating a flap of adjacent skin such as described in Chapter 11.

with smoking, anoreceptive intercourse, and immunosuppression has also been described. A relationship with human papillomavirus (HPV) types that are known to be associated with cervical and other genital cancers has been established. Individuals who engage in anal intercourse and who are infected with HPV type 16 have a relative risk of developing anal canal cancer as high as 33% over the general population.76 Palmer and colleagues affirmed that both HPV types 16 and 18 are involved in the development of anal and genital squamous cell carcinoma.108 Youk and associates identified HPV type 16 in all 21 of their patients with anal cancer.166 High-risk HPV is found in 85% of patients with anal squamous cancer, depending on the assay used. Holmes and associates found associations between positive herpes simplex virus 2 titer, cigarette smoking, a prior positive or questionable cervical Papanicolaou smear, and an increasing number of sexual partners with the development of anal cancer.65 An increased incidence of cancers in the anogenital region has also been observed in patients who have undergone renal transplantation, presumably as a consequence of immunosuppression.117 Anal cancers have occurred following radiation therapy for pruritus.37

TABLE 25-1 Incidence Rates by Race | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 25-2 Stage Distribution and 5-Year Relative Survival by Stage at Diagnosis for 2001-2007, All Races, Both Sexes | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Prior radiotherapy

Chronic anal fistula

Crohn’s disease

Smoking

Positive Papanicolaou smear

Cervical carcinoma

HPV infection

Hodgkin’s disease

Renal transplantation

Multiple partners

Positive herpes simplex virus 2 titer

HIV infection

Male homosexuality

Anoreceptive intercourse

Immunosuppression

Positive serologic test for syphilis

Anal condylomata

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN)

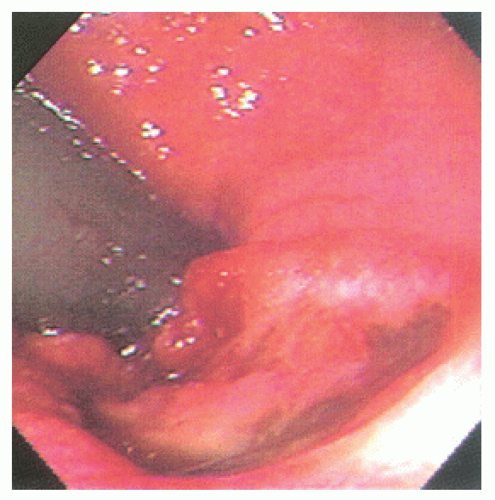

FIGURE 25-5. Squamous cell carcinoma. The patient complained of a lump. (From Corman ML, Veidenheimer MC, Swinton NW. Diseases of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. Part I: Neoplasms. New York, NY: Medcom; 1972, with permission.)28 |

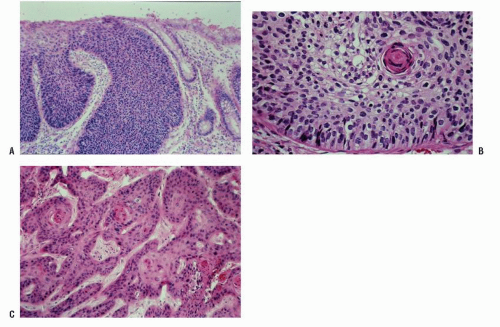

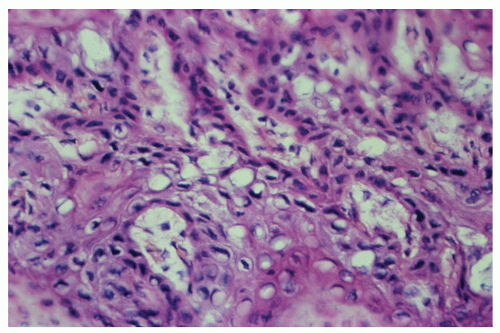

morphologically resembles carcinoma arising from the buccal mucosa, esophagus, uterine cervix, and so forth. The tumor is composed of squamous epithelial cells that resemble normal anal mucosa to a varying extent, depending on the degree of differentiation. The more differentiated tumors have readily apparent keratin formation, either as pearls or as individual cell keratinization (Figure 25-8). The lesions can be graded based on the degree of keratinization and the nuclear morphology, and this grade correlates with the behavior of the tumor, that is, well-differentiated tumors tend to be less deeply invasive and are less likely to metastasize. More than 50% of anal canal tumors are nonkeratinizing, whereas 80% are poorly differentiated.37 This is in contrast to anal margin tumors, with 80% demonstrating keratinization and 85% being well differentiated.37

of the transitional or “cloacogenic” zone and suggested that tumors, which arise in this area, differ from the usual epidermoid carcinomas originating in the squamous epithelium of the distal anal canal.60 They proposed the term transitional-cloacogenic for these lesions. Subsequent studies have confirmed the morphologic difference from that of the usual squamous carcinomas.78,109

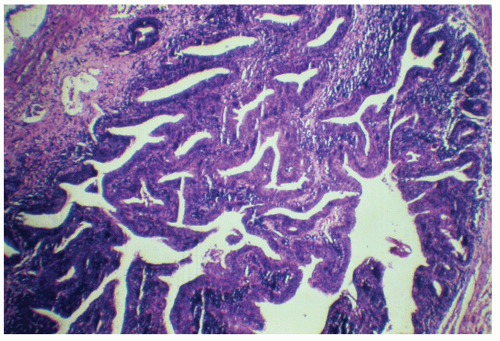

comparable to that of epidermoid carcinomas of similar grade and stage (Figure 25-12). There are fewer published studies of transitional-cloacogenic tumors than that of epidermoid carcinoma, but evidence suggests that there is sufficient overlap in the epidemiology (e.g., an increased incidence in analreceptive homosexual men),25 the clinical presentation, and the results of treatment that, for the purposes of management, one should consider the two entities identical.

anoplasty will usually be curative (see Chapter 11). For more deeply invading tumors such as those that invade the internal sphincter, local excision including the internal sphincter may also achieve cure. However, for tumors that invade more deeply than the internal sphincter, APR has, historically, been the preferred alternative. These differences in therapy based on the stage of the tumor require precise preoperative evaluation, including careful digital examination to assess the depth of invasion and endoanal ultrasound. Tarantino and Bernstein evaluated 13 consecutive patients with biopsyproven squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal by means of endoanal ultrasound.152 These investigators proposed the following staging system:

TABLE 25-3 The AJCC Staging System for Anal Canal Cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree