Chapter 31 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

PRINCIPLES OF MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Varying certain acquisition parameters, especially timing, changes the images so that their contrast varies depending more on their interactions with each other (T1-weighted imaging) or on their interactions with their local environment (T2-weighted imaging). Many other techniques and strategies are employed to vary the contrast, sensitivity, and efficiency of MRI and much more complete descriptions are available to the interested reader.1

MRI VERSUS OTHER IMAGING MODALITIES

The following sections include illustrative cases of normal anatomy and benign pathology frequently encountered by reproductive surgeons. The focus is on congenital and acquired pathology, but we do not discuss differentiation of a benign or malignant cyst. The assessment of malignant versus benign cysts is most commonly determined by ultrasonography (see Chapter 30).

NORMAL ANATOMY

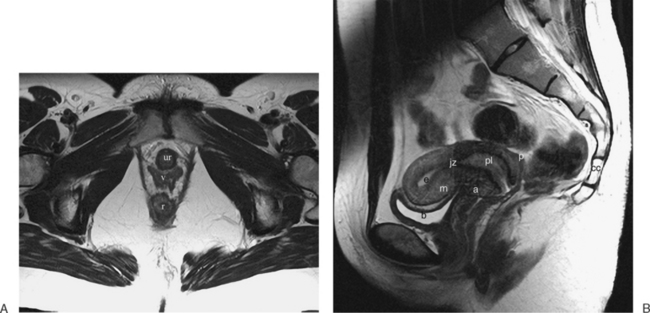

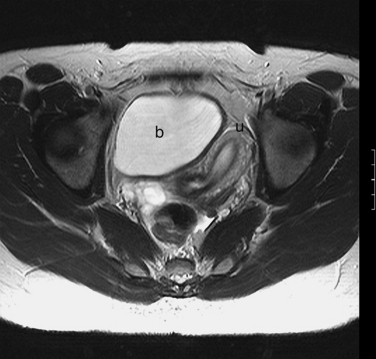

The normal uterus, cervix, vagina, endometrium, and ovaries can be readily identified on T2-weighted images in a variety of planes. Also the plicae palmitae, the anterior and posterior fornix, the cul-de-sac, rectum, urinary bladder, and urethra are easily identified (Fig. 31-1). The uterine MRI anatomy can be subdivided. The signal intensity and thickness of these layers can vary based on the hormonal milieu. The myometrium is seen externally and tends to be intermediate in signal intensity. Centrally is the endometrium, which tends to be of increased signal on T2-weighted sequences. Between the two layers is a much darker, uniform layer, called the junctional zone. Although histologically similar to the adjacent myometrium, the difference in signal intensity is believed to result from a lower water content relative to the adjacent myometrium3 and the compact longitudinally oriented smooth muscle bundles oriented parallel to the endometrium4 (see Fig. 31-1). The radiologist, when assessing the uterus for pathology, evaluates the thickness, signal characteristics, and distinctness of each of these zones.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES OF THE REPRODUCTIVE TRACT

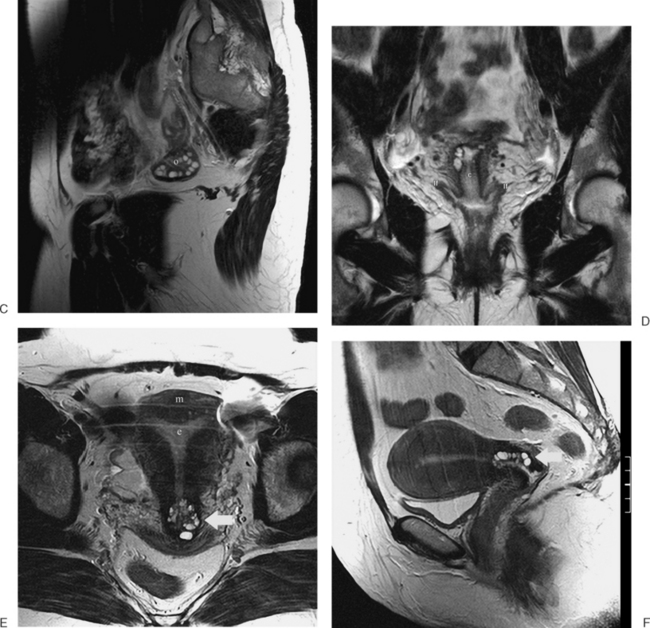

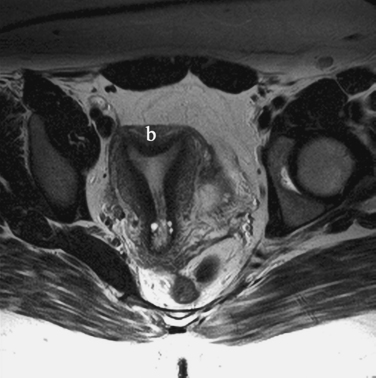

The MRI appearance of müllerian anomalies directly corresponds to the findings on both hysterosalpingography and gross examination. Several potential anatomic observations can be made. In cases of uterine agenesis, no vaginal or uterine tissue is present (Fig. 31-2).

The arcuate uterus is a frequent müllerian anomaly that usually has little clinical significance and is identified as a contour or “bulge” of the fundus, with no changes associated with the endometrial canal (Fig. 31-3).

Several anomalies are easily determined by MRI, such as a unicornuate uterus where a single horn can be identified (Fig. 31-4). However, others are more difficult, especially when the decision of whether to proceed to surgery relies on the MRI diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree