Lymphadenectomy (LAD) is an important staging and treatment modality of oncologic surgery. LAD in genitourinary malignancies presents inherent difficulties to the urologist and pathologist because of the differences in anatomic sites and primary histologic type. This review focuses on pathologic evaluation and how communication between urologist and pathologist is necessary to provide optimal care. Recommendations covering general specimen submission and processing are discussed, as well as more specific recommendations concerning the kidney, upper urinary tract, urinary bladder, prostate, testes, and penis. Emerging areas of prognostic significance and the impact that improved molecular techniques are contributing to diagnostic interpretation are highlighted.

Lymphadenectomy (LAD) in genitourinary (GU) cancer is an area in which close communication and understanding between the urologist and pathologist are required to ensure the procedure fulfills its potential to the patient. Although the primary histologic type of tumor varies between anatomic sites, lymph node status still plays a major role in the staging in all of these cases and is an integral part of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria ( Table 1 ).

| Kidney | |

|---|---|

| Stage | Stage Category Definitions |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| Renal pelvis and ureter | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in a single lymph node, 2 cm or less in greatest dimension |

| N2 | Metastasis in a single lymph node, more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension; or multiple lymph nodes, none more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node, more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| Bladder | |

| NX | Lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Single regional lymph node metastasis in the true pelvis (hypogastric, obturator, external iliac, or presacral lymph node) |

| N2 | Multiple regional lymph node metastasis in the true pelvis (hypogastric, obturator, external iliac, or presacral lymph node metastasis) |

| N3 | Lymph node metastasis to the common iliac nodes |

| Prostate | |

| pNX | Regional lymph nodes not sampled |

| pN0 | No positive regional nodes |

| pN1 | Metastases in regional node(s) |

| Testes | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| pN1 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass 2 cm or less in greatest dimension and less than or equal to 5 nodes positive, none more than 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| pN2 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension; or more than 5 nodes positive, none more than 5 cm; or evidence of extranodal extension of tumor |

| pN3 | Metastasis with a lymph node mass more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

| Penis | |

| pNX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| pN0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| pN1 | Metastasis in a single inguinal lymph node |

| pN2 | Metastasis in multiple or bilateral inguinal lymph nodes |

| pN3 | Extranodal extension of lymph node metastasis or pelvic lymph node(s) unilateral or bilateral |

This review discusses current recommendations on handling and submission protocols for the urologist and pathologist involving LAD specimens in GU oncologic surgery. To accomplish this goal, particular recommendations for the kidney, upper urinary tract, urinary bladder, prostate, penis, and testes, and their respective primary cancer types, are detailed. In addition, the use and appropriateness of intraoperative frozen sections are discussed. To conclude, how emerging molecular techniques are affecting the way pathologists report findings in LAD specimens is investigated. However, to begin an overview of the large similarities in specimen submission and pathologic evaluation is given.

Specimen submission and processing

The initial step in determining if optimal conditions are met for lymph node assessment in LAD lies with the urologist. Of primary consideration is how the urologist submits the specimen, specifically en bloc or as separate/fragmented parts. The literature supports the submission of the LAD specimens in separate, properly labeled parts. In doing so, the urologist is able to relay to the pathologist accurate, in vivo assessment of location and, in addition, maximize inspection by decreasing associated soft tissue. Submission of nodes en bloc was reported by Stein and colleagues to reduce median total lymph nodes removed from 68 in the separately packaged group to 31 in the en bloc group. Because of this finding, the submission method directly affected important nodal prognostic indicators of total positive lymph nodes and the dependent figure of lymph node density.

In addition, it is helpful to the pathologist if the urologist submits their assessment of nodes removed at the time of specimen submission. Besides these intraoperative considerations, it is the responsibility of the urologist to ensure that the LAD specimens are placed as quickly as possible in fixative (10% buffered formalin) so that the tissue does not degrade before pathologic evaluation.

Once these crucial initial steps have been fulfilled, it becomes the responsibility of the pathologist that the specimen is dissected and documented properly to obtain maximal diagnostic tissue for microscopic examination. Because LAD specimens are generally received with attached fatty soft tissue, careful palpation and sectioning through the specimen must be undertaken to identify all possible nodes. Submission of 1 section of any grossly positive lymph node is allowed, but complete submission of all other nodes is required, along with documentation of any remarkable features (eg, calcification, hemorrhage, necrosis). It is generally recommended to use 2-mm to 4-mm sections when sectioning the specimen. Along with the number of nodes submitted, documentation of the size of grossly positive nodes, extranodal extension, the size of metastases present, and histologic grade of metastases present is required, because this may affect prognosis and staging.

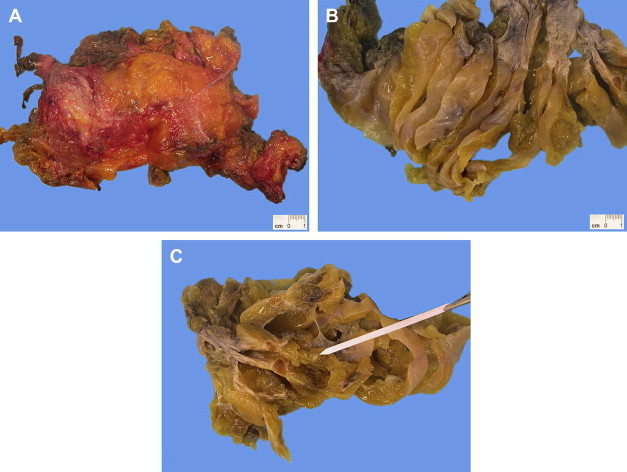

Should examination of submitted tissue not reveal any or inadequate lymph nodes, placement in lymph node revealing solution (LNRS) is recommended to enhance lymph node yield ( Fig. 1 ). This procedure is particularly important when an institutional minimum node submission policy is in place because processing of the specimen can occur without LNRS first and can then be used only in situations in which the minimum number is not met. A subsequent examination after placement in LNRS that still yields no or inadequate lymph nodes warrants submission of all received adipose tissue labeled by the urologist as a submitted node or attached to the main specimen, if received en bloc. The total number of nodes submitted is important and highlights one of the major site-specific discrepancies in pathology reporting of LAD specimens.

Kidney

LAD in the kidney in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of contentious debate. The low prevalence of nodal metastases has convinced some against broad use of the procedure, whereas others have shown survival benefits to the procedure. Recent evidence has shown that lymph node stage represented the most informative variable and achieved independent predictor status of cancer-specific survival. This finding has been shown to be especially true when there are no synchronous distant metastases; distant metastases diminish the prognostic impact of involved nodes when present. Because of this situation, locoregional lymph node status may become an increasingly important staging/therapeutic procedure. However, detailed analysis of this controversial argument in RCC is beyond the scope of this review; until a consensus is reached, it is apparent that many urologists choose to perform LAD, and the pathologist must be aware of what is important to both the urologist and the patient.

Crispen and colleagues advocate that when an LAD is performed in the setting of RCC, it should be performed from the crus of the diaphragm to the common iliac artery, involving the nodes of the ipsilateral great vessel and the interaortocaval region. It lies within the responsibilities of the pathologists to assess the specimen received and, if not received separately labeled, it may be necessary to contact the urologist to accurately judge anatomic geography of the specimen.

A consensus number on minimum nodes has not yet been established. However, the recent literature supports 13 as an accepted minimum. Crispen and colleagues showed a significantly greater percentage of nodal disease, 20.8% versus 10.2%, in similarly risk-stratified patients. Hence, if the pathologist is unable to locate 13 nodes during gross examination and no nodal disease is found on microscopic examination, more tissue needs to be submitted for possible nodes missed on the first examination or the urologist needs to be informed that the LAD is likely inadequate.

Recently, evaluations have taken place on the usefulness of frozen section diagnosis in patients with RCC as an adjunct to clinical and imaging risk stratification for nodal involvement. Ming and colleagues reported that frozen section diagnosis had a sensitivity, specificity, concordance, and false-negative rate of 88.9%, 100%, 96.5%, and 11.1%, respectively. Furthermore, these investigators made the claim that many enlarged nodes turn out to be benign. Crispen and colleagues reported similar figures. However, others have claimed that if the low morbidity and benefit to staging and possible treatment preclude the value of frozen section and in patients at risk, LAD should proceed. Communication between the urologist and pathologist is necessary so that an agreed procedure at their particular institution can be conducted until a consensus is reached.

As per the AJCC Staging Manual, Seventh Edition , the pathologist’s report must also include other data that are considered prognostic factors. These data include extranodal extension, size of metastasis in involved lymph nodes, and size of the largest tumor deposit in the lymph nodes.

Kidney

LAD in the kidney in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of contentious debate. The low prevalence of nodal metastases has convinced some against broad use of the procedure, whereas others have shown survival benefits to the procedure. Recent evidence has shown that lymph node stage represented the most informative variable and achieved independent predictor status of cancer-specific survival. This finding has been shown to be especially true when there are no synchronous distant metastases; distant metastases diminish the prognostic impact of involved nodes when present. Because of this situation, locoregional lymph node status may become an increasingly important staging/therapeutic procedure. However, detailed analysis of this controversial argument in RCC is beyond the scope of this review; until a consensus is reached, it is apparent that many urologists choose to perform LAD, and the pathologist must be aware of what is important to both the urologist and the patient.

Crispen and colleagues advocate that when an LAD is performed in the setting of RCC, it should be performed from the crus of the diaphragm to the common iliac artery, involving the nodes of the ipsilateral great vessel and the interaortocaval region. It lies within the responsibilities of the pathologists to assess the specimen received and, if not received separately labeled, it may be necessary to contact the urologist to accurately judge anatomic geography of the specimen.

A consensus number on minimum nodes has not yet been established. However, the recent literature supports 13 as an accepted minimum. Crispen and colleagues showed a significantly greater percentage of nodal disease, 20.8% versus 10.2%, in similarly risk-stratified patients. Hence, if the pathologist is unable to locate 13 nodes during gross examination and no nodal disease is found on microscopic examination, more tissue needs to be submitted for possible nodes missed on the first examination or the urologist needs to be informed that the LAD is likely inadequate.

Recently, evaluations have taken place on the usefulness of frozen section diagnosis in patients with RCC as an adjunct to clinical and imaging risk stratification for nodal involvement. Ming and colleagues reported that frozen section diagnosis had a sensitivity, specificity, concordance, and false-negative rate of 88.9%, 100%, 96.5%, and 11.1%, respectively. Furthermore, these investigators made the claim that many enlarged nodes turn out to be benign. Crispen and colleagues reported similar figures. However, others have claimed that if the low morbidity and benefit to staging and possible treatment preclude the value of frozen section and in patients at risk, LAD should proceed. Communication between the urologist and pathologist is necessary so that an agreed procedure at their particular institution can be conducted until a consensus is reached.

As per the AJCC Staging Manual, Seventh Edition , the pathologist’s report must also include other data that are considered prognostic factors. These data include extranodal extension, size of metastasis in involved lymph nodes, and size of the largest tumor deposit in the lymph nodes.

Upper urinary tract and urinary bladder

The literature strongly supports the role of LAD in the staging and treatment of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. In addition, it has been shown to offer curative potential. Despite the well-accepted nature of the practice, variation on extent and adequate number of nodes submitted/sampled still exists.

The studies described earlier reported a median lymph node range of 4 to 8, all showing benefit to the patient. This small, but narrow, range of nodes submitted further emphasized the importance of close communications between urologists and pathologists. The pathologist can use LNRS to increase the yield of small nodes if correlation between estimated nodes submitted and nodes retrieved during gross examination is not achieved.

LAD in the setting of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder is well researched ( Fig. 2 ). Standard nodal dissections have been shown to remove a mean of as high as 23 nodes, but much discrepancy and controversy exist over the minimum number of nodes required for adequate LAD. Data from 9 of the largest series have shown an average number of lymph nodes removed to be 13. Others have shown clinical benefit occurs only in patients with 16 nodes or more removed. May and colleagues specifically cited an increase in 5-year cancer-specific survival from 72% to 83% when 16 or more nodes are removed. Even higher goals are used by some.

Of particular note in the studies collected in the review by Hurle and Naspro is increased cancer-specific survival of patients with negative or independent node status when compared with those with positive nodes. For instance, in the report by Leissner and colleagues, lymph node retrieval of 16 or more nodes showed a 5-year cancer-specific survival of 65% to 51% in those with less than 15 in the independent status group; this decreased to 35% and 23%, respectively, in those with positive node status. Similar 5-year results were obtained by Herr and colleagues when comparing those with negative node status with 8 or more and less than 8 (82% and 41%, respectively) and those with positive node status with the 3-tiered nodes removed observation groups of more than 14, 9 to 14, and 1 to 8 nodes (50%, 38%, and 18%, respectively).

The simple establishment of an institutional minimum number, which has been shown to increase sampling and diagnostic yield, may prove beneficial in its own right. We recommend a minimum number of 8 nodes as an attainable and consistently achievable goal in standard LAD for urothelial cancer of the urinary bladder.

An important consideration when interpreting these numbers is that they apply to standard pelvic LAD. When an extended LAD is performed by the urologist, reports have shown a mean yield of 51 nodes per patient. Because of this large discrepancy, the urologist must communicate to the pathologist that an extended LAD has been performed to avoid misrepresenting nodal removal. To address this situation, Park and colleagues propose that the number of lymph nodes removed has no impact on patient survival, but, instead, emphasize the adherence to the LAD template performed by the urologist and proper communication with the pathologist, allowing for optimum lymph node evaluation.

As a result of some of the controversy associated with lymph node numbers, the concept of lymph node density (positive lymph nodes per total number of lymph nodes) has been used and reported in numerous studies to show clinical significance. The significant ratio seems to consistently be 20% nodal involvement. Five-year disease-free survival is reported to decrease from 54.6% in those with 20% or less versus 15.3% for those with more than 20%. Furthermore, it has been proposed that lymph node density, rather than absolute number, may provide a better estimate of good surgical technique.

However, lymph node density is a dependent variable with lymph node number. Therefore, when interpreting studies that show additional benefit with ever-increasing lymph node retrieval, it must be recognized that they are, in turn, decreasing lymph node density in those patients and placing those patients at a higher chance of entering the beneficial 20-node-or-less density category. However, Jeong and colleagues have reported that in patients with 15 lymph nodes or more removed, lymph node density was the only predictor of cancer-specific survival after multivariate analysis.

An additional prognostic indicator from LAD is extranodal extension. Fleischmann and colleagues reported that overall survival in the presence of extracapsular extension decreases from 60 months in those without extranodal extension to 12 months in those patients with extranodal extension identified.

The AJCC Staging Manual, Seventh Edition specifically cites reporting the number of nodes, the number of nodes involved by cancer, and the extent of location of positive nodes involved. The use of intraoperative frozen sections for LAD for urinary bladder cancer is essentially limited to those cases in which the urologist is considering forgoing LAD if nodal disease is discovered.

Prostate

In the modern era, evidence from the literature and widespread usage of nomograms that complements the concomitant increase in screening have reduced the overall frequency of LAD being routinely performed in the setting of radical prostatectomy for prostatic adenocarcinoma ( Fig. 3 ). Recent work has begun to show benefit in the procedure; however, it is likely that many urologists choose to perform the procedure in those patients they believe will benefit from the procedure. Nomograms exist to assist the urologist in electing to proceed with LAD in only those patients whose benefit from the procedure will outweigh the associated surgical morbidity. These nomograms incorporate Gleason score, clinical stage, and prostate-specific antigen and, therefore, requires input from both the pathologist and urologist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree