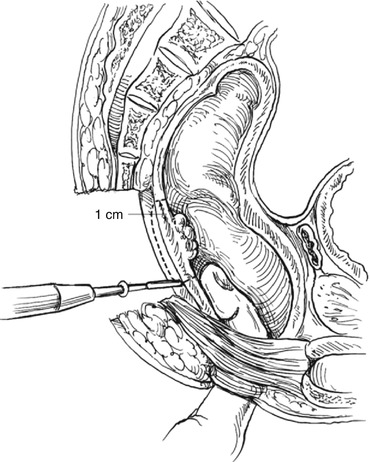

Fig. 43.1

(a–c) Transanal excision. (a) A transanal excision is performed by marking out a 1 cm or greater margin around the tumor. (b) A full-thickness excision is then performed to obtain adequate radial as well as lateral margins. (c) The specimen is then oriented accurately for the pathologist

If visualization is not initially adequate, serial traction sutures should be used to prolapse the lesion into the field of view. Next, the electrocautery is used to make a full-thickness incision along the previously marked mucosa, typically starting at the caudal aspect (Fig. 43.1b).

The specimen is then oriented accurately for the pathologist (Fig. 43.1c). Upon completion of this excision, the perirectal fat should be visible beneath the lesion to confirm a full-thickness excision.

For anterior lesions, care must be taken not to injure the back wall of the vagina in females or the prostate or membranous urethra in males.

The defect in the bowel wall is then closed transversely, if possible, using interrupted 2-0 or 3-0 polyglycolic sutures.

The complications most commonly associated with transanal excisions include urinary retention, urinary tract infections, delayed hemorrhage, infections of the perirectal and ischiorectal space, and fecal impactions. The overall incidence of these complications is quite low, and the mortality rate is 0 % in most series.

Transcoccygeal Excision

The transcoccygeal approach was used historically over the transanal approach for larger, more proximal lesions. It was originally popularized by Kraske who found it beneficial when operating on lesions within the middle or distal third of the rectum. This approach is especially useful for lesions on the posterior wall of the rectum but can certainly be used for anterior or lateral lesions as well.

After undergoing a full antibiotic and mechanical bowel preparation, the patient is placed in the prone-jackknife position with the buttocks taped apart after the induction of general anesthesia. The tape is released to facilitate the approximation of the subcutaneous tissues and skin and an incision is made in the posterior midline adjacent to the sacrum and coccyx down to the upper border of the posterior aspect of the external sphincter.

The coccyx, which along with the anal coccygeal ligament lies immediately deep to the skin and subcutaneous tissue, is removed to improve exposure. In order to do so, the anal coccygeal ligaments and other attachments are cauterized from each side and from the lower edge of the coccyx.

The dissection then proceeds along the undersurface and anterior edge of the coccyx until a cutting wire can pass through the sacral coccygeal joint. The coccyx is then removed with occasional bleeding from an extension of the middle sacral artery, which is easily controlled with electrocautery.

The levator ani muscles visible at the base of the wound are separated in the midline, exposing a membrane that resides just outside of the perirectal fat. Division of this membrane allows for complete mobilization of the rectum within the intraperitoneal pelvis.

For posterior-based lesions, the distal margin of the tumor can be palpated via a rectal examination, and then the mesorectum and rectum are transected at a point 1–1.5 cm distal to the tumor (Fig. 43.2). The excision is then completed with a 1-cm margin surrounding the lesion.

Fig. 43.2

Transcoccygeal excision. For posterior lesions using a transcoccygeal or “Kraske” approach, one can palpate the lower border of the tumor to ensure an adequate distal margin

For anterior lesions, a posterior proctotomy is made, and then the lesion is approached under direct vision, again excising the lesion down to the perirectal fat with a 1-cm margin (Fig. 43.3).

Fig. 43.3

Transcoccygeal excision. Anterior lesions need to be approached by first making a posterior proctotomy and then excising the lesion through the rectum. The anterior and posterior walls of the rectum then need to be repaired, usually in a transverse manner in order to maintain the lumen diameter

Following removal, the specimen is reoriented for the pathologist and all the rectal incisions are closed in either a longitudinal or transverse manner in order to avoid narrowing of the rectum, using an absorbable suture. An air test should be performed, filling the operative field with sterile saline and insufflating air in the rectum in order to check for air leaks in the suture line. Once these air leaks are controlled, the levator ani is reapproximated in the midline. The operation is completed with the closure of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

An unfortunate complication of this procedure is the development of a fecal fistula that extends from the rectum to the posterior midline incision. The incidence of this complication ranges from 5 to 20 %, and most heal after temporary diversion of the fecal stream via a loop ileostomy or colostomy. For this reason, the Kraske approach is used much less frequently.

Transsphincteric Excision

The transsphincteric approach developed by York and Mason involves the complete division of the sphincters and the posterior wall of the rectum.

Patients undergo an antibiotic and mechanical bowel preparation on the day before surgery. General anesthesia is chosen for the operation.

The procedure starts similarly to the Kraske transcoccygeal approach; except the levator ani and the external sphincter muscles are divided in the midline. These muscles are carefully tagged, so matching sutures can be reapproximated exactly at the end of the procedure. Care must be taken to remain in the midline in order to avoid the nerve supply to the sphincters that lie in a posterolateral position bilaterally.

Once the lesion is removed, the rectum, sphincters, and overlying musculature are closed in a careful stepwise manner.

This procedure has an increased risk of incontinence secondary to sphincter dysfunction. Since the exposure provided from this approach is similar to that from the Kraske procedure, which carries less of a risk of incontinence, there are very few indications for this technique.

Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery

TEM was developed by Gerhard Buess and the Richard Wolf Medical Instruments Company in 1983 in Germany. Originally designed for the removal of large rectal polyps beyond the reach of traditional transanal excision, its indications eventually expanded to include the excision of early-stage rectal cancers.

TEM is essentially the earliest natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). It utilizes endoluminal insufflation to create rectal distension and exposure. Access is obtained via a proctoscope 4 cm in diameter and either 12 or 20 cm in length, which allows for resection of lesions anywhere in the rectum. Visualization is provided by a special binocular optic passed through the proctoscope which provides three-dimensional viewing. In addition, a laparoscopic camera can be attached to a separate optic with the image being viewed on a standard video monitor.

TEM is a closed system and a faceplate on the end of the proctoscope maintains an airtight seal. Instruments are passed through three-gasket ports, similar to laparoscopy. All instruments are 5 mm in diameter and >30 cm in length and include graspers, cautery, needle holders, suction, scissors, and clip appliers.

Recently, modifications of TEM have been described, utilizing single-port laparoscopy devices and standardized laparoscopic instrumentation (TAMIS – transanal minimally invasive surgery)

Briefly, the technique is as follows. The lesion and its location are precisely identified and the patient is positioned on the operating room table with the lesion oriented toward the floor (i.e., prone for anterior lesions, lithotomy for posterior lesions). This is important as the TEM equipment is designed to operate from “the top down.”

The proctoscope is inserted, the lesion is located, and the proctoscope is then fixed in place by attaching it to the “Martin Arm,” a three-elbowed gadget that attaches to the OR table, locks in place, and keeps the TEM scope fixed (Fig. 43.4). Lidocaine with epinephrine is instilled underneath the lesion and 1-cm margins (5 mm for benign lesions) are marked with electrocautery surrounding the lesion. Using cautery, the lesion is then excised circumferentially in the full-thickness plane until it has been completely detached from the surrounding rectal wall (Fig. 43.5).

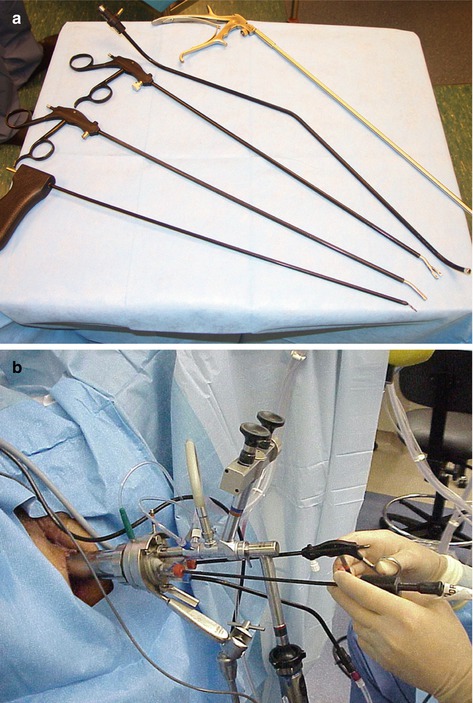

Fig. 43.4

(a) Five-millimeter TEM instruments, including needle cautery, graspers, suction, and needle holder. (b) External view of assembled TEM equipment in use

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree