Introduction

The first successful transplant occurred in Boston in 1954, when a surgical team under the direction of Joseph Murray removed a kidney from a healthy donor and transplanted it into his identical twin, who had chronic glomerulonephritis [1]. The organ functioned immediately and the recipient survived for 9 years, after which time his allograft failed from what was thought to be recurrent glomerulonephritis. More than 50 years have passed since that breakthrough achievement, and transplantation has progressed from an experimental modality to standard of care. The introduction of immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine, prednisone, and later calcineurin inhibitors has led to better outcomes and, along with technical breakthroughs, expanded the pool of organs available to deceased and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-mismatched donors.

Kidney transplantation has become the preferred therapeutic option for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), leading to better patient survival and quality of life. It is also more cost-effective than dialysis [2–4]. Unfortunately, the incidence of ESKD has risen steadily in the past several decades, creating a shortage of available organs for patients on the kidney-transplant waiting list (Table 1.1).

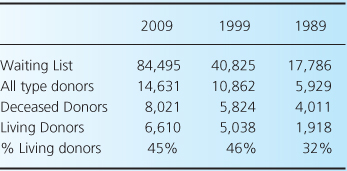

Table 1.1 Waiting list for different organs in the USA. OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Data from [5].

| Waiting list candidates OPTN 2010 | Number |

| All | 107,075 |

| Kidney | 84,495 |

| Pancreas | 1,458 |

| Kidney/Pancreas | 2,182 |

| Liver | 15,948 |

| Intestine | 248 |

| Heart | 3,173 |

| Lung | 1,844 |

| Heart/Lung | 75 |

This growth in ESKD is related to the increased incidence of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension, combined with the improvement in treatment for concurrent health problems such as ischemic heart disease and stroke. The supply of organs from deceased donors has not followed the same upward trend, resulting in an ever-widening gap between eligible potential transplant recipients and available organs (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Growth of the kidney-transplant waiting list compared to donor type in the USA. Data from [5].

In 2009, only 18% of patients on the waiting list for kidney transplantation received an organ [5]. The average waiting time for kidneys from deceased donors in the USA is more than 3 years, and in some geographic areas it is more than 5 years (Table 1.3)—waiting times that are sometimes longer than the average life expectancy of middle-aged and older persons with ESKD [6]. In line with these numbers, a recent study indicates that even major alterations in the organ procurement process cannot reasonably be expected to meet the demand for transplantable kidneys from decreased donors [7]. The imbalance between patient demand and the supply of organs from deceased donors has refocused attention on living kidney donors.

Table 1.3 Time to transplant by organ type in the USA. Data from [5].

| Organ type | Time to transplant in 2004 (median in days) |

| Kidney | 1,219 |

| Pancreas Transplant Alone | 376 |

| Pancreas after Kidney | 562 |

| Kidney-Pancreas | 149 |

| Liver | 400 |

| Intestine | 212 |

| Heart | 166 |

| Lung | 792 |

Epidemiology

Living-donor kidney transplantation is rapidly increasing in popularity worldwide and has surpassed the number of deceased donors in many transplant centers [5]. In 2009, approximately 40% of all kidney donations were from living donors, and most major transplant centers in the USA have been increasing the proportion of living donors, reaching more than 60% of total transplants in some. However, wide variations exist worldwide in the use of living and deceased kidney donors. These differences reflect varying medical, ethical, social, and cultural values, as well as the availability of deceased-donor organs. For example, Spain has possibly the most efficient system of deceased-organ collection, with less than 5% of transplants being from living donors. At the other end of the spectrum, strong cultural barriers in Japan have led to a preponderance of living-organ transplantation. Similarly, Turkey and Greece rely mainly on living donation as a source of organ transplantation [8].

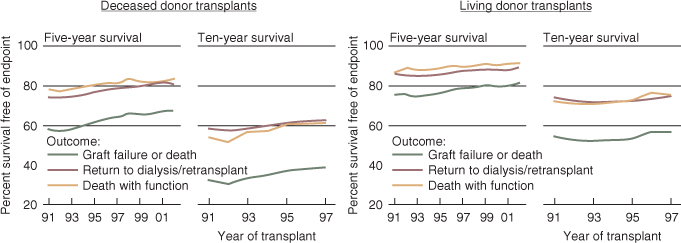

Several factors have influenced the expansion of living donation. The advent of laparoscopic nephrectomy has reduced the associated morbidity of kidney removal, making more donors receptive to an interruption of the healthy course of their lives. Just as importantly, epidemiological data have shown that irrespective of the HLA match or the donor–recipient relationship, recipients of living-donor kidneys (LDKs) fare better than those who receive deceased-donor kidneys (DDKs) (Figure 1.1). Finally, the development of stronger immunosuppression and desensitization techniques has overcome many of the biological barriers to successful transplantation, such as ABO incompatibility or the presence of low to medium titers of antidonor HLA antibodies (Abs). Today, any person who is well and willing to donate may potentially be a live-kidney donor.

Figure 1.1 Outcomes of kidney transplants according to donor type. Graft-survival estimates are adjusted for age, gender, race, and primary diagnosis, using Cox proportional-hazards models. Conditional half-life estimates depend on first-year graft survival. (Reproduced from [6] The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government)

Advantages of living-kidney donation

It is well recognized that renal dysfunction is associated with accelerated heart disease. It has been estimated that mortality associated with cardiovascular disease is increased approximately 10-fold among patients with ESKD, even after accounting for age, sex, race, and the presence of diabetes [9]. Successful kidney transplantation progressively reduces the incidence of cardiac mortality and is therefore associated with an overall survival benefit in subjects undergoing kidney transplantation [10]. Even in older transplant recipients and patients with ESKD secondary to diabetes or obesity—subgroups with higher perioperative cardiovascular complications—survival benefits persist [4, 11].

One-year survival for a functioning transplant is 90% for recipients of deceased-donor transplants and 96% for recipients of transplants from living donors. After surviving the first year with a functioning transplant, 50% of recipients of deceased- and living-donor transplants are projected to be alive with a functioning transplant at 13 and 23 years, respectively.

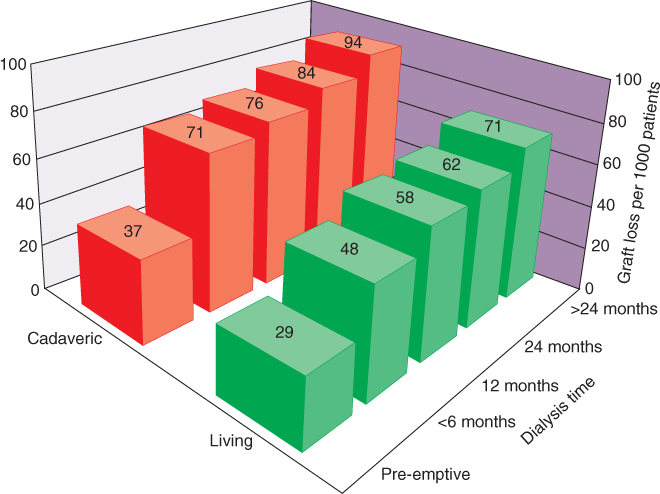

The waiting time on dialysis has emerged as one of the strongest independent modifiable risk factors for poor renal-transplant outcome [12], as can be seen in Figure 1.2. The presumed negative effect of prolonged dialysis is likely related to the impact of ESKD on cardiovascular morbidity and is observed in both living- and deceased-kidney recipients. However, even after a prolonged wait, patients who eventually receive a kidney transplant still have a lower mortality than those who continued on dialysis [13]. The possibility of undergoing preemptive transplantation without the need for dialysis gives the ESKD patients the best possible outcome [13–15]. With these observations in mind, until an optimal and timely source of organs is developed to decrease the prolonged waiting times, living-kidney-donor transplantation provides the best alternative for most patients [13–15].

Figure 1.2 Comparison of rates of graft loss associated with living- and deceased (cadaveric)-donor transplantation according to time on dialysis prior to transplantation [12]. (Reproduced from [12], Copyright © 2002, (C) 2002 Lippincott Williams)

Living-kidney donation is an act of profound human generosity and can be a source of much gratification for all parties involved. Many donors describe it as the most meaningful experience of their lives and the quality of life of donors after transplantation is reported to be better than or equivalent to that of controls [16]. Nonetheless, given the highly asymmetric nature of the physical benefits arising from kidney donation, a careful psychiatric evaluation of the donor is essential, to assess the coercion-free, informed, and autonomous decision to proceed with the process.

The number of sensitized recipients has increased dramatically in the past couple of years and these recipients usually face the greatest waiting times, due to the presence of preformed antibodies, and consequently have the greatest mortality. Desensitization protocols have enabled them to plan and receive an LDK at a determined time, but these protocols are expensive and labor-intensive, and in the USA have been implemented only for small numbers of patients. While successful in the short-term, the long-term outcomes remain unknown; these techniques are discussed further in Chapter 5. Another potential option for such patients is a paired-kidney exchange (PKE), which is discussed in more detail later in this chapter. For many years, immunological barriers were thought to be the largest hurdle in transplantation; today, many cite the acute shortage of organs as the major limitation.

Finally, the administration of donor-derived cells into the recipient in order to induce immunological hyporesponsiveness to the solid-organ transplant and minimize the need for immunosuppression has recently been explored. This hyporesponsiveness was thought to occur due to the generation of mixed chimerism, immune deviation, and/or generation of a regulatory immunological phenotype. Kawai et al. have recently published a report on a small number of successful cases of combined bone-marrow and kidney transplant in HLA single-haplotype mismatched, living, related donors, with the use of a nonmyeloablative preparative regimen. Four out of five recipients were able to discontinue all immunosuppressive therapy 14 months after transplantation, opening new possibilities for the induction of transplant tolerance with living-kidney donation, with consequent improvement in long-term outcomes [17].

In summary, living donation provides one answer to the shortage of donor organs, allows preemptive transplantation, and leads to better long-term graft survival. It also permits the introduction of new, tolerogenic strategies, and for many donors will be a very positive and meaningful experience.

Types of donor

Related versus unrelated donors

Whereas rates of kidney transplantation from living related donors increased during the 1990s, transplantation from living unrelated (including spousal) donors has increased rapidly over the past decade, now accounting for nearly one-quarter of all transplantations from living donors in the USA (Figure 1.3). In 1995, a landmark report by Terasaki and colleagues documented that HLA-mismatched spousal transplants resulted in a graft survival superior to that of anything but identically matched kidneys from deceased donors [14]. This observation has influenced decisions regarding the suitability of live donors who are spouses, friends of the recipient, or anonymous; there is little concern today about the degree of HLA matching for the crossmatch-negative recipient of a kidney from a living donor. With directed donation to loved ones or friends, concerns have arisen about the intense pressure that can be put on people to donate, leading those who are reluctant to do so to feel coerced. Donor evaluation by a team of physicians other than that treating the recipient and a focus on the donor’s interests when evaluating for donation minimize these risks. Furthermore, the general approach of simply reporting an unwilling donor as ‘unsuitable’ is a safe method of protecting the donor’s decision without harming their relationship with the recipient.