Lateral Lymph Node Dissection for Rectal Carcinoma

Petr Tsarkov

Badma Bashankaev

Introduction/Objectives

Recent progress in rectal cancer staging, development of surgical procedures (e.g., total mesorectal excision [TME] and nerve-sparing TME), and advances in neo- and adjuvant therapy (such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy [RT]) has dramatically reduced locoregional recurrence but still has not eliminated it (1). Local recurrences are likely to be a result of one of the following reasons—missed microscopic involvement of circular resection margin, rare involvement of distal mesorectum beyond “5 cm” barrier, lateral spread to pelvic lymph nodes beyond the mesorectum and possibly seeding of the pelvis during surgical dissection (2).

When reviewing series of patients who developed local recurrence after radical TME, lateral pelvic wall involvement is found in 20–80% of them (3,4,5). Thus, lateral lymph nodes (LLN) can be a potential site of locoregional recurrence even in the absence of circumferential margin involvement. Lateral lymph nodes recurrence (LLR) to pelvic sidewalls may be even higher (up to 83%) in patients with primary locally advanced rectal cancer (1). That phenomenon can be explained by recently found connections between the mesorectal and (lateral) extramesorectal lymph node system (6). The authors have suggested a hypothesis that a lymphatic fluid including cancer cells is squeezed into the LLN system. Since standard TME does not include lateral lymph node dissection (LLD) those nodes are not included in the standard surgical specimen. In addition lymph fluid might leak and form a presacral seroma that might also give a rise to local recurrence.

Unfortunately the widespread idea of relying on neoadjuvant therapy as a radiotherapy “mop” to sterilize low rectal cancer is currently accepted in Western countries. The use of preoperative RT as was shown in a large randomized Dutch study demonstrated a significant reduction of LLR in irradiated patients (7). The benefits of preop RT include about a 15–25% likelihood of complete pathologic response and tumor shrinkage and/or downstaging (8,9). But RT holds a significant potential risk of urinary and sexual dysfunction, and possible postoperative fecal incontinence (10,11,12).

There is no proven correlation between the regression of a primary tumor and the regression of regional nodal disease. The rate of pathologically proven metastatic mesorectal and lateral pelvic lymph nodes in low rectal cancer patients may be as high as 39% even after the completion of neoadjuvant RT (13).

Along with neoadjuvant chemoRT, surgical procedures to prevent LLN metastasis have been proposed, such as LLD. Although Western surgeons attempted LLD as early as the 1950s (14,15,16), this procedure is currently favored in East, mostly in Japan. The current approach towards LLNs in most Western colorectal centers, as noted by Yano and Moran, is to ignore their presence, or to treat obviously involved nodes with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. More importantly, involved nodes are considered to be systemic disease (17).

The incidence of lateral nodal involvement in patients with lower rectal cancer has been reported as 16–23%. It has been demonstrated that in patients with pathologically proven lateral nodal involvement LLD results in a 5-year survival rate of 25–50%.

Mori has presented the data from Japanese registry, which showed that LLNs involvement was present in 1.1% of cases of T1 rectal cancers, 3.1% with T2 involvement, 11.6% with T4a penetration, and almost 15% in case of T4b invasion. Involvement of lateral nodes resulted in 32% 5-year survival rate in this group of patients (18).

In the review of neoadjuvant chemoRT and TME surgical treatment of 366 patients with rectal cancer, Kim et al. have reported that LLN metastasis is the major cause of locoregional recurrence (1).

Locoregional recurrence despite all modern trends of neoadjuvant chemoRT and TME attest to the need for more intense surgical research and/or technical improvements.

Indications

The indications for LLD are still controversial even amongst Japanese surgeons.

Since preoperative imaging modalities are close to the desired predictive value for LLN only in few centers (19), the criteria for LLD are derived from analyzing other factors. There have been reported several risk factors predictive of lateral nodes involvement, some of which can be determined before operation.

The most predictive risk factors are as follow:

Tumor location below the level of peritoneal reflexion, and the lower the tumor the higher the incidence of lateral node metastasis. Takahashi et al. (20) have demonstrated that in patients with rectal tumors above peritoneal reflexion the incidence of LLN involvement is 1.7%, while for the tumors below peritoneal reflexion this rate is 16.7% (P < 0.001), with maximum of 36.8% for tumors located just above the dentate line.

Depth of tumor invasion—through bowel wall (T3) and infiltrating fascia propria of the rectum and adjacent organs (T4). The highest incidence of positive LLNs of 10.0–27.2% has been demonstrated for tumors invading mesorectal fat (T3) and 27.3–31.0% for cancer involving adjacent organs and structures (T4) (20,21). Multivariable analysis performed by Sugihara and colleagues (22) revealed that tumors below peritoneal reflexion as well as female sex, tumor size of more than 4 cm and T3/4 stage were significantly associated with an increased incidence of positive LLNs.

Tumor histological grade—moderately and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas have higher chances of metastases to LLNs.

Based on results of multiple studies, the current Japanese decision concerning paraaortic and LLN dissection is determined by location of tumor, its histological grade, and stage of cancer (25). All patients with middle and lower rectal cancer classified as

Dukes’ C undergo LLD. Prophylactic LLD is performed for Dukes’ B tumors with G2 or G3 features (moderately and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas) in order to remove LLNs with possible micrometastasis.

Dukes’ C undergo LLD. Prophylactic LLD is performed for Dukes’ B tumors with G2 or G3 features (moderately and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas) in order to remove LLNs with possible micrometastasis.

Precise preoperative diagnosis of both primary tumor characteristics and lateral nodal involvement, thus, define indications for LLD but remain difficult. The utility of endorectal ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in predicting T-stage has been demonstrated in multiple studies, whereas the ability to evaluate lymph node status using these methods is relatively poor (26).

A recently published meta-analysis of 35 clinical trials of endorectal US in the diagnosis of nodal involvement in patients with rectal cancer demonstrated by pooled analysis sensitivity of 73.2% with a better ability to exclude rather than confirm nodal invasion (27). In a recent prospective study any visible mesorectal and LLNs on 5-mm thick section preoperative CT were recognized as positive, and postoperative histopathology assessment confirmed high sensitivity (95%) and specificity (96%) of CT in predicting LLN status. The new technique of visualizing metastatic mesorectal lymph nodes on MRI images after injection of USPIO (ultra-small particles of iron oxide) was assessed in several studies and showed promising preliminary results in revealing metastatic lymph nodes (26,27). Still there is no report on LLN assessment with the use of this technique.

Tan et al. reviewed more than 1,000 rectal cancer cases and found that when a combination of three or more variables was present—female sex, tumors that were not well differentiated, pathological T3 and above, positive microscopic lymphatic invasion, and positive mesorectal nodes—the odds of lateral node metastasis were more than 7.5 times higher (P < 0.001) than in cases when less than three variables were noted (28).

Preoperative planning includes a thorough physical examination. Enlarged inguinal lymph nodes should be noted. Physical examination, including digital rectal examination, vaginal inspection, and regional lymph node assessment may help to assess the possible risk of LLN involvement.

Rigid proctoscopy is performed to assess the accurate distance from lower border of the tumor to the anal verge and/or dentate line. Colonoscopy is required to identify any synchronous lesions. However, barium or Gastrografin enema is helpful in cases with severe tumor stenosis.

Although some authors are not suggesting chest CT as a routine diagnostic tool (29), all our patients are undergoing chest CT in order to exclude pulmonary metastasis.

A routine examination list includes an abdominal US or an abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast.

In cases with nonobstructing cancer a rectal US is performed to stage the lesion. A phased-array MRI is obtained by colorectal surgery-oriented radiologist is a vital part of the multidisciplinary approach to the treatment. MRI identification of LLN >5 mm with irregular borders, mixed MR-signal intensity, or both is considered as highly suspicious for tumor involvement. LLN location, number, and their relation to any neighboring anatomic structures should be clearly noted.

Positioning

The patient is positioned in Lloyd-Davies position in Allen stirrups. Safe positioning of the patient’s bony prominent part is very important; padding of neurovascular bundles is performed to prevent their damage. The surgeon is initially positioned on the left side of the patient, the first assistant is positioned on the right side, and second assistant is positioned between the patient’s legs. During surgery the surgeon can change sides several times as needed. After induction of anesthesia, an additional digital rectal examination is performed to verify the tumor location, height, mobility, and the involvement of any other organs.

Technique

A laparotomy is performed through a lower midline incision; great care is taken not to damage the bladder, which is usually dissected and retracted to the left as the 2 cm above pubic bone is quite important to optimize adequate visualization of the lower pelvis. After the midline laparotomy and intra-abdominal inspection a wound retracting system is installed. The surgeon retracts the small bowel, right colon, omentum, and proximal left colon under the blades of the retractor in order to open the sigmoid colon and its mesentery. The optimal view should include the duodenum as an upper border, aorta and vena cava on the right side with the white line of Toldt on the left side.

The modern principles of extended upward and LLN dissection imply complete removal of all fatty tissue from the para-aortic and lateral pelvic areas with maximum preservation of pelvic autonomic nervous system in all levels.

According to Japanese concepts based on early anatomic studies of Senba (30) and Kuru (31), the rectal muscle tube is surrounded by three fat-tissue “spaces”. The first space corresponds to mesorectum that is enveloped by rectal fascia propria. Two hypogastric nerves and the pelvic plexuses are attached to both postero-lateral sides of mesorectum. Adjacent to the nerves lie the right and left second fat-tissue spaces. Lateral borders are the internal iliac vessels and their visceral branches. The left and right third spaces are located lateral to internal iliac vessels in both obturator fossae. Since establishing as a standard in Japanese colorectal surgery, this three-space dissection around the rectum is considered essential to achieve complete pelvic lymph node dissection in all three areas.

We perform para-aortic lymphadenectomy on a routine basis for all rectal, sigmoid, and left colon cancers.

The usual way to enter the preaortic space is to lift the sigmoid mesocolon in lateral-to-medial direction. The white line of Toldt along sigmoid colon is incised with monopolar electrocautery starting above the promontorium and all way up to the descending colon. It is essential to enter the embryologic interfascial avascular layer between sigmoid mesocolon fascia propria and renal fascia. The method of traction and countertraction is helpful in achieving that. The first assistant lifts the sigmoid colon gently handling it in the middle while the operator is dissecting the back of sigmoid mesentery off the underlying tissues. This maneuver helps to maintain left ureter safe below the dissection plane and visualize autonomic nervous structures. As soon as the left hypogastric nerve or hypogastric plexus is reached, it is carefully peeled off from the mesentery surface and left intact on the aorta.

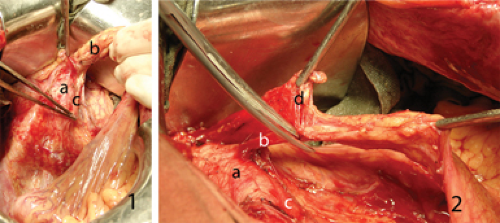

The sigmoid colon is moved to the left and drawn upwards, the operator incises peritoneum at the root of its mesentery above the aorta. Using fine forceps the first assistant lifts the medial edge of peritoneal incision in the countertraction way. Thus the preaortic space is entered from the medial side. The described lateral and medial incisions meet to form reach-through hole above the aorta just above the hypogastric plexus. The operator enters this space with left index finger and uses it like a hook to lift the dissected vascular bundle off the aorta (Figure 36.1.1). Due to this maneuver good exposure of autonomic nerves and left ureter is assured. The peritoneal incision is extended upwards until the third part of duodenum is reached. The latter is gently retracted cranially and carefully dissected off. So left angle incision is formed with vertical part

projecting to aorto-caval space and horizontal part—to lower border of duodenum. The origin of inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) is 2.5–3.0 cm lower the horizontal incision.

projecting to aorto-caval space and horizontal part—to lower border of duodenum. The origin of inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) is 2.5–3.0 cm lower the horizontal incision.