■ Ulcer

■ Diverticula

■ Stricture

■ Intussusception

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Obstruction results in nausea, vomiting, obstipation, abdominal pain, and distension with absent bowel sounds. Peritoneal signs and fever may indicate ischemia, necrosis, or perforation.

■ Bleeding may result in hematemesis, hematochezia, or heme-positive stools. Additionally, a brisk bleed may result in hemodynamic instability with hypotension and tachycardia. Abdominal pain is typically absent, unless bleeding is associated with ulcer disease or obstruction.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Computed tomography (CT) with oral and intravenous (IV) contrast can assist with the location and etiology of obstruction. A transition point is noted when the proximal small bowel is dilated and the distal small bowel is decompressed.

■ Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance enteroclysis (MRE) along with CT may assist with the diagnosis of small bowel tumors.1

■ Tagged red blood cell (RBC) scan and CT angiogram may localize intraluminal bleeding in cases where bleeding rates are at least 0.1 to 1.0 mL per minute.

■ A technetium-99m pertechnetate, or Meckel scan, can detect gastric mucosa associated with a Meckel’s diverticulum.

■ Small bowel enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy may also be used to identify the location of a tumor or site of bleeding in a stable patient. If small bowel enteroscopy is performed, the location of the tumor can be tattooed for easy intraoperative identification.

■ Diagnostic laparoscopy can assist with localization of disease and can help avoid unnecessary laparotomy.

■ An elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and lactate level is concerning for ongoing ischemia or necrosis.

■ A decrease in hemoglobin or hematocrit is indicative of bleeding.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ The patient requires adequate IV access for resuscitation and, if necessary, blood transfusion if bleeding.

■ A nasogastric tube assists in gastric and proximal small bowel decompression. This decreases the risk of aspiration during intubation as well as injury to the stomach or small bowel during port placement.

■ A Foley catheter is placed for accurate intraoperative assessment of urine output and also to decompress the bladder for safe port placement.

■ Preoperative antibiotics should cover enteric organisms in the event of spillage.

Positioning

■ The patient is placed in the supine position. Arms may be out at 90 degrees or tucked at the side of the patient. Tucking the arms may assist with the ergonomics of the operation as both surgeon and assistant may stand on the side of the patient comfortably.

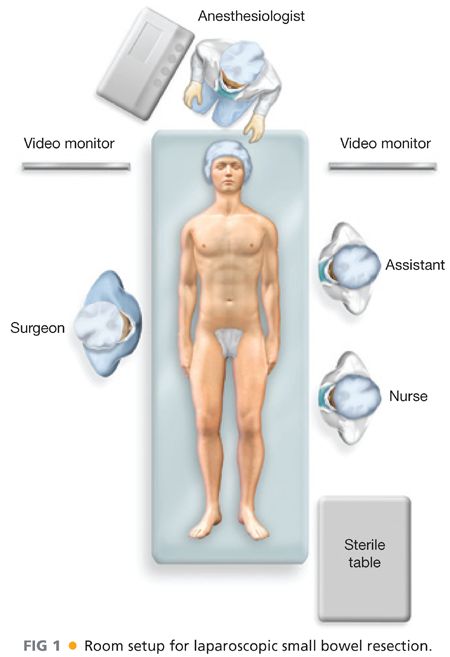

■ For operations that take place on the proximal small bowel, it is optimal for the surgeon to stand on the patient’s right (FIG 1). Meanwhile, for operations that take place in the distal small bowel, it is optimal for the surgeon to stand on the patient’s left.

■ Operations that take place solely on the duodenum may be performed in split-leg position.

TECHNIQUES

ACCESS TO THE ABDOMINAL CAVITY

■ Accessing the abdominal cavity can be performed in a variety of ways based on surgeon’s comfort (i.e., open cut-down technique vs. Veress needle insufflation). An open cut-down technique may be advantageous in the setting of obstruction because the chance of blindly injuring dilated bowel is lower.

■ Typical insufflation settings for laparoscopy include an intraabdominal pressure of 15 mmHg and a flow of 20 L per minute.

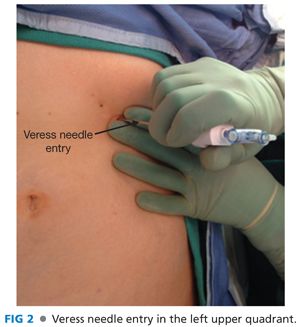

■ Veress needle entry

■ With a nasogastric tube in place and the stomach decompressed, a stab incision with a no. 11 blade is made through the dermis in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, below the costal margin in the midclavicular line (FIG 2).

■ A Veress needle is placed through this incision and advanced until two distinct clicks are heard, signaling that the blunt-tip portion of the Veress needle has sprung forward. The second click is heard as the needle enters the peritoneal cavity.

■ A “drop test” can be performed by placing 10 mL of saline through the needle using a syringe without a plunger (FIG 3). If the saline drops into the abdominal cavity with gravity alone, then the needle may be connected to the insufflator (FIG 4).

■ Once the abdomen is fully insufflated to an intraabdominal pressure of 15 mmHg, the Veress needle is removed and a 5-mm port is placed through the same incision. The port is then connected to the insufflator.

■ Open cut-down technique

■ A 2-cm curvilinear incision is made with a no. 11 blade just below the umbilicus and tissue is dissected down to the level of the fascia.

■ S-shaped or L-shaped retractors are placed to assist with exposure.

■ The umbilical stalk is then grasped with a Kocher and elevated, thus pulling the fascia away from the underlying bowel.

■ A 2-cm longitudinal incision is made in the fascia with a no. 15 blade, and the edges are grasped and retracted using Kocher clamps. The peritoneum is identified below, grasped with DeBakey forceps in two separate locations, and then incised under direct vision.

■ A Hasson port is placed into the abdominal cavity and then connected to the insufflator.

PORT PLACEMENT

■ After the first port is placed, a laparoscope is introduced into the abdominal cavity. A 5-mm or 10-mm, 30-degree angled laparoscope is used to perform the operation.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree