(1)

Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Kameda Medical Center, Kamogawa, Japan

Keywords

Laparoscopic sigmoidectomyFusion fasciaFascial composition3.1 Introduction

Laparoscopic sigmoidectomy (LapS) involves the basic procedures of the laparoscopic surgery. However, many errors occur in the recognition of the correct fascial anatomy and understanding of the surgical technique. Procedures based on clinical anatomy should be performed.

In this procedure, we assume the reader is a beginner in a non-established facility rather than a skilful surgeon in an established facility. Many facilities that currently perform surgery based on inaccurate clinical anatomy are likely already in a condition that cannot be easily rectified. This is also evident from the fact that the basics of the fascia anatomy have not been revised in these facilities.

3.2 Fundamentals Related to the Sigmoid Colon

Basics of the sigmoid colon of each patient must be understood preoperatively. The border of the sigmoid colon and descending colon is defined as the iliac crest (according to the Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma; JCCC [1]), which is located near the height of the navel. From the supine abdominal X-P and enema examination or computed tomography (CT)-colonography (CTC) it is possible to understand the running of the sigmoid colon. It is desirable that results from both the CT-angiography in addition to the CTC are available. The umbilicus substantially coincides with the aortic bifurcation [2, 3]. In addition, the root of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) is an indicator of the lymph node dissection and is often located about 3–5 cm distal from the umbilicus. However, since it is often shifted caudally with age [4], it is necessary to verify this with the CT examination. Performing the operation having this information, you will see the procedure site within the vascular system with the left forceps inserted at the height of the umbilicus.

3.3 Resection Range and Degree of the Lymph Node Dissection

LapS is very similar to open sigmoidectomy, in terms of the resection range and the degree of lymph node dissection, except the approaches into the abdominal cavity. The length and extent of the resection based on the positional relationship of the sigmoid colon differ, also anastomosis are diverse from the oral side to the anal side, thus it is necessary to periodically take into account the methods of anastomosis. Lymph node dissection in sigmoid colon cancer is performed according to the lymph node mapping obtained from the CT examination, which is an improved high quality approach for the detection of lymph nodes. Very few patients are indicated for a high tie operation performed by dividing the root of the IMA for lymph node dissection at the origin of the IMA. A low tie operation reserved for the inferior mesenteric root nodes and the left colic artery (LCA) is sufficient dissection for most cases with sigmoid colon cancer [5]. In addition, we often perform the low tie operation with lymph node dissection at the origin of the IMA.

3.4 Fascial Composition and Fusion Fascia of the Descending Colon and Sigmoid Colon

The descending colon and sigmoid colon are embryologically connected by an abdominal wall through the dorsal mesentery where the vessels and nerves run and control mobility. The mobility of the descending colon disappears after the formation of the left fusion fascia of Toldt that forms between the left (dorsal) leaf of the descending mesocolon and the parietal retroperitoneum at the end of the intestinal rotation. In contrast, the adjacent relationship to the sigmoid colon differs depending on the length and the flexion of the sigmoid colon. Due to incomplete fusion of the dorsal mesentery and retroperitoneum, the fan-shaped sigmoid fossa is typically formed behind the sigmoid mesocolon in this process (Fig. 3.1). This vertical root and oblique root act as a border between the left (dorsal) leaf of the sigmoid mesocolon and the retroperitoneum. Figure 3.1 (arrows) shows the left fusion fascia of Toldt; dissection along these arrows is impossible because the two fasciae are already fused.

Fig. 3.1

Fascial composition and fusion fascia of the sigmoid colon. Mobility of the descending colon disappears after formation of the left fusion fascia of Toldt with the left leaf of the descending mesocolon fusing to the parietal retroperitoneum at the end of intestinal rotation. The sigmoid colon shows many variations depending on its length and flexion. An incomplete fusion of the dorsal mesentery and retroperitoneum typically results in the formation of the fan-shaped sigmoid fossa behind the sigmoid mesocolon [6, with permission]

Dissection and mobilisation of the sigmoid mesocolon involves dissecting between the left fusion fascia of Toldt and the deep subperitoneal fascia (Fig. 3.2). The phrase dissection inside the fusion fascia is a fundamental error in consideration of the definition of the word (Fig. 3.3).

Fig. 3.2

Fusion of the sigmoid mesocolon and its cross-sectional view. The arrows indicate the dissecting layer between the fusion fascia of Toldt and the deep subperitoneal fascia by the lateral approach [6, with permission]

Fig. 3.3

Dissecting layer of the sigmoid colon (Incorrect rationale). The consideration for dissection inside the fusion fascia is a fundamental error derived from the misunderstanding of the definition of the word

In addition, at the cranial-most side of the sigmoid fossa, there is often a small peritoneal recess, which is believed to be formed by a fusion deficit between the descending mesocolon and the parietal peritoneum at the innermost part of the descending colon. This area is known as the intersigmoid fossa, also known as a cause of internal hernia (intersigmoid hernia) (Fig. 3.1). On the other hand, this area is also an anatomical landmark used to identify the ureter; the urinary tract is located on the surface of the iliopsoas, and has been considered generally found parallel to the spermatic vessels. Note that this intersigmoid fossa should not be confused with the sigmoid fossa.

In a cross-sectional view of the caudal part of the sigmoid colon (Fig. 3.4), the sigmoid fossa is added and then the new fascia is added on the ventral (deeper) side of the deep subperitoneal fascia. In Fig. 3.1 considering the sigmoid colon, the left fusion fascia of Toldt and the sigmoid fossa are shown. Arrow I indicates the formation of the fusion fascia between the left (posterior) leaf of the sigmoid mesocolon and the parietal pleura. In addition, arrow II shows that the left fusion fascia of Toldt continues to the cranial side. In Fig. 3.4 a new fascia is added to the ventral side of the deep subperitoneal fascia. This new fascia seems to fuse with the deep subperitoneal fascia at its most cranial part. In the rectum, this fascia is called the fascia propria of the rectum; it is a concept derived from the embryological interpretation of organ dominance of the autonomic nerve fibres by Dr. Takahashi [6–10]. At the most caudal side the sigmoid fossa becomes wider and there may be cases where the fusion fascia is formed on both sides (Fig. 3.5). In this textbook, the fascia covering the mesorectum will be called the fascia propria of the rectum and the continuing fascia from the fascia propria of the rectum laterally will be called the neuro-vascular corridor (For more information, see the Chap. 4).

Fig. 3.4

Cross-sectional view of the caudal side of the sigmoid fossa. The sigmoid fossa is added and the new fascia is added onto the ventral (deeper) side of the deep subperitoneal fascia. It is the fascia propria of the rectum [6, with permission]

Fig. 3.5

Cross-sectional view of the most caudal side of the sigmoid fossa. At the caudal-most side, the sigmoid fossa becomes wider. There may be cases where the fusion fascia is formed on both sides

3.5 Operative Procedures (in Men)

3.5.1 Intraoperative Positions, the Trocar Site and Elimination of the Small Intestine

(See the Chap. 2).

3.5.2 Operative Procedures

Sigmoidectomy is performed using either a lateral or a medial approach. In recent years, the medial approach is performed in most facilities. We believe that the idea of anatomical recognition by the lateral approach is indispensable, so both approaches are destined to become more accepted. The lateral approach is necessary for left colectomy and resection of the splenic flexure of the colon. In this textbook after the description of the medial approach, the lateral approach is added as supplementary information.

3.5.2.1 Dissection and Mobilisation of the Sigmoid Colon with the Medial Approach

Dissection and Mobilisation of the Sigmoid Colon from the Medial Side

Scope: at the beginning umbilical port, and the right cranial port.

The operator’s right hand: a electrosurgical knife with spatula-type blade.

The operator’s left hand: holds the bowel forceps from the umbilical port.

Tension is required to aid the procedures using the electrosurgical knife in the medial approach.

It is a mirror image for the assistant.

The assistant’s right hand: almost free (or is used for lifting the right caudal rectum to the ventral side with bowel forceps).

The assistant’s left hand: lifts the vascular pedicle of the IMA to the ventral-caudal side to form a 30° angle with the aorta.

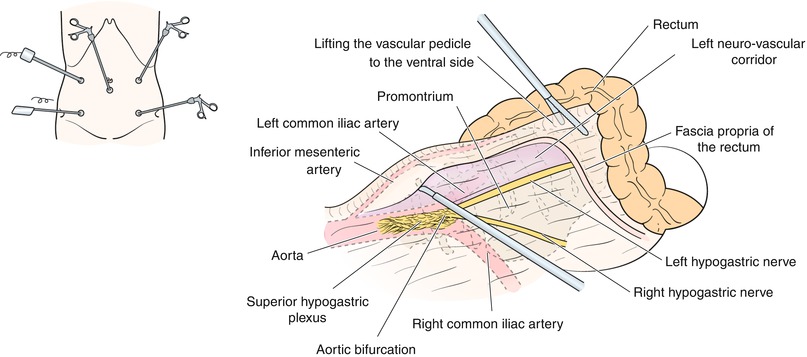

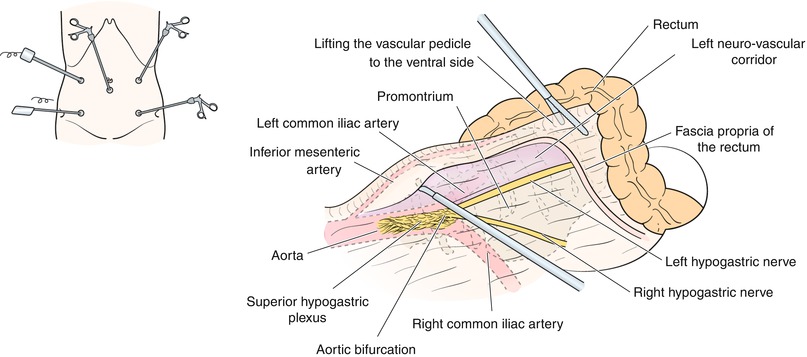

The medial approach of the sigmoid colon is ultimately the dissection between the fusion fascia of Toldt and the deep subperitoneal fascia. Factors that modify this procedure include the neuro-vascular corridor and the nerves from the inferior mesenteric plexus. The fascia composition in the field of view in which the IMA has been lifted ventrally is clearly different comparing the cranial and the caudal sides of the superior hypogastric plexus. At the cranial side, the ventral side of the superior hypogastric plexus is the dissection plane and the inferior mesenteric plexus should be divided around the IMA (Fig. 3.6a). At the caudal side, the neuro-vascular corridor converges to the superior hypogastric plexus and should be divided at two sites (Fig. 3.6b).

Fig. 3.6

Cross-sectional view of the medial approach. The inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) has been lifted on the ventral side. In the superior hypogastric plexus, the dissecting layer is ventral to the plexus (a). In the dissecting layer of the caudal side, the neuro-vascular corridors are divided into two locations and the surgeon can thus enter the ventral side of the deep subperitoneal fascia covering the ureter (b)

After incision of the peritoneum at the caudal side, the right and left neuro-vascular corridors are divided along the fascia propria of the rectum. Then the deep subperitoneal fascia is lifted ventrally and is dissected dorsally. Continuing the dissection of the deep subperitoneal fascia caudally, the sigmoid fossa comes into view. How to deal with these two fasciae: two routes can be considered (Fig. 3.6b). In the medial approach, the dissection is performed towards the root of the IMA cranially while confirming the left neuro-vascular corridor. In the cranial side of the superior hypogastric plexus, the deep subperitoneal fascia is easily dissected from the left fusion fascia of Toldt (Fig. 3.6a).

The vascular pedicle of the IMA is grasped with the assistant’s left forceps and is lifted to the ventral-caudal side to form a 30° angle with the aorta with the laparoscope inserted in the umbilical port (Fig. 3.7). At this time, viewing the right rectal peritoneum can confirm that there is no additional branch of vascular pedicle besides the gripped vasculature.

Fig. 3.7

The start of the division and the dissection from the medial side. The surgeon palpates the portion of the promontorium with the forceps. On carefully viewing the sigmoid mesocolon at the ventral side of the promontorium, the boundary between the parietal and visceral pleura is detected by a colour change, and the slightly ventral side of the boundary is incised

With the laparoscope inserted in the right cranial port, the surgeon’s left hand forceps is inserted in the umbilical port. The surgeon palpates the portion of the promontorium with the forceps to share the recognition of the anatomy with the staff (Fig. 3.7). On carefully viewing the sigmoid mesocolon at the ventral side of the promontorium, the boundary between the parietal and visceral pleura is detected by a colour change, and the slightly ventral side of the boundary is incised (Fig. 3.7). The incision should be as thin as possible and continue cranially along the IMA. At this point, the neuro-vascular corridor exists as a screen with sufficient width ventro-dorsally.

The surgeon moves to procedures for identifing the fascia propria of the rectum at the promontirium portion. There is no anatomical landmark to aid in this procedure. The procedure alone is essential to dissect the crude tissue with a right angle toward the dorsal side of the rectum that has been lifted ventrally (Fig. 3.8b). After detection of the fascia propria of the rectum, the surface of the fascia propria of the rectum is maintained and the procedure proceeds cranially, dividing the vessels and nerves of the right neuro-vascular corridor along the right side of the fasciae. The left neuro-vascular corridor should not be incised at this time (Fig. 3.9). After dividing the vessels and the nerves of the right neuro-vascular corridor as far as possible to the cranial side, there is a dense tissue around the root of IMA. This is the inferior mesenteric plexus with the lumbar splanchnic nerve and the ascending branches around the IMA (Fig. 3.10). The ascending branches along the IMA should be divided.

Fig. 3.8

Cross-section view of the division and the dissection from the medial side. The surgeon moves to standard procedures for identifying the fascia propria of the rectum at the promontorium portion (b). There is no anatomical landmark to aid in this procedure. Only the procedure is essential to dissect the crude tissue with a right angle toward the dorsal side of the rectum that has been lifted ventrally

Fig. 3.9

Dissecting of the fascia propria of the rectum leading to the superior hypogastric plexus. After detection of the fascia propria of the rectum, the surface of the fascia propria of the rectum is maintained, and the procedure proceeds cranially, dividing the vessels and nerves of the neuro-vascular corridor along the right side of the fascia. The left neuro-vascular corridor should not be incised

Fig. 3.10

The inferior mesenteric plexus with lumbar splanchnic nerve. After dividing the vessels and the nerves of the neuro-vascular corridor as much as possible, there is a dense tissue around the root of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). This is the inferior mesenteric plexus with lumbar splanchnic nerve and the ascending branches around the IMA

After identifying the aortic bifurcation as the anatomical landmark, a triangular fascia from the superior hypogastric plexus to the fascia propria of the rectum can be identified. It is the left neuro-vascular corridor, which contains nerves and small vessels (Fig. 3.10). The vessels and the nerve of left neuro-vascular corridor are divided ventrally from the cranial side (Fig. 3.11). After this corridor is incised, it is possible to identify the deep subperitoneal fascia and the ureter that can then be lifted ventrally to the fusion fascia of Toldt. Continuing the dissection of the deep subperitoneal fascia and the ureter to the dorsal side, typically the sigmoid fossa is revealed. How to handle the fasciae of the sigmoid fossa: two routes can be considered (Fig. 3.6b). Normally it is better to dissect the dorsal side of the sigmoid fossa and dissect the deep subperitoneal fascia as far as possible to the left lateral side. In this way, the spermatic vessels are detected on the major psoas muscle. If the dissection exceeds these vessels, the medial approach is sufficient.

Fig. 3.11

Dissection of the left neuro-vascular corridor. After viewing the aortic bifurcation anatomical landmark, the vessels and the nerve of left neuro-vascular corridor are divided at the ventral side from the cranial side

The medial approach is easy to explain using two cross-sections, cranial and caudal. At the cranial side, the deep subperitoneal fascia is dissected from the left fusion fascia of Toldt that is raised like a screen, so it is possible to enter the layer for mobilisation of the sigmoid colon (Figs. 3.10 and 3.12). At the caudal section, if the neuro-vascular corridor is divided, the dissection can be continued towards the dorsal side of the left fusion fascia of Toldt and towards the dorsal side of the sigmoid fossa; the dissection is continued to mobilise the sigmoid colon (Figs. 3.10 and 3.13). As a consequence, the left ureter is confirmed on the dorsal side of the deep subperitoneal fascia. Furthermore, it is easier to dissect and mobilise from the lateral side if the sigmoid mesocolon is sufficiently dissected.

Fig. 3.12

Cross-section of the dissection of the sigmoid mesocolon (cranial side). At the cranial side, the deep subperitoneal fascia is dissected from the left fusion fascia of Toldt that is raised like a screen, so it is possible to enter the mobilisation layer for mobilisation of the sigmoid colon

Fig. 3.13

Cross-section of the dissection of the sigmoid mesocolon (caudal side). At the caudal section, if the neuro-vascular corridor is divided, the dissection can be continued towards the dorsal side of the left fusion fascia of Toldt and towards the dorsal side of the sigmoid fossa; the dissection is continued to mobilise the sigmoid colon

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree