Laparoscopic Resection Rectopexy

Martin Luchtefeld

Dirk Weimann

There are many surgical options to choose from when treating a patient for rectal prolapse. The sheer number and diversity of choices suggests that there is no perfect answer for all circumstances. The choices can be broadly categorized into four: (a) sigmoid resection/rectopexy, (b) rectopexy with or without mesh, (c) perineal proctosigmoidectomy (Altemeier’s procedure), and (d) Delorme procedure. The first two options, both abdominal procedures, can be done either open or laparoscopically. The first consideration while selecting the appropriate operation is whether or not the patient is medically fit to undergo a major abdominal operation. Abdominal approaches are felt to have a lower recurrence rate but are associated with a greater risk of complication. The perineal approaches are associated with a higher recurrence rate but are tolerated better with fewer complications.

If a patient is medically fit for an abdominal surgery, both sigmoid resection/rectopexy and rectopexy alone have good outcomes with low recurrence rates. However, rectopexy alone has a higher risk of postoperative constipation, even in patients with normal bowel habits prior to the procedure. Sigmoid resection/rectopexy is a better choice for the constipated patient but carries the small but real risk of anastomotic leak that is not an issue for the patient undergoing rectopexy alone. Sigmoid resection/rectopexy then is ideally suited for the medically fit patient who already suffers from constipation.

Sigmoid resection/rectopexy can be done as an open or laparoscopic procedure. Early in the history of laparoscopic colon and rectal surgery, rectal prolapse surgery was thought to be an ideal disease process for the laparoscopic approach: it is a benign illness, it is noninflammatory, and the mesentery tends to be redundant and relatively easy to address. Multiple studies of laparoscopic-aided sigmoid colectomy/rectopexy have now been published and when compared to the open version, the recurrence rates appear to be similar while short-term outcomes such as length of stay are superior.

Prior to surgery, the diagnosis of rectal prolapse must be verified during physical examination. Visualizing and identifying rectal prolapse is not always straightforward. Evaluating the patient on an examining table may not be sufficient to confirm rectal prolapse. If the diagnosis has not been made during the usual examination, the patient can be placed on the commode and then reexamined after several minutes of straining. Once the prolapse has been reproduced, the diagnosis is usually quite obvious. However, occasionally, it can be difficult to distinguish full-thickness rectal prolapse from mucosal prolapse or significant prolapsing hemorrhoidal disease. If uncertainty remains, identification of the circular folds of the full-thickness rectal prolapse will confirm the diagnosis.

Before making a final decision for a resection/rectopexy, it is important to evaluate the colon with colonoscopy (or some other form of full evaluation) to be certain that there is no other significant pathology present that might alter the surgical plan.

Anal physiologic studies also need to be considered preoperatively. For the patient with fecal incontinence, anal manometry, intra-anal ultrasound, and pudendal nerve terminal motor latency testing can provide documentation of the preoperative physiologic status. Conversely, for the patient with no impairment, these studies would add little value.

Many of these patients will suffer from constipation as well. In addition to the colonoscopy mentioned previously, colonic transit studies and defecography can be done.

Technique

Preoperative Preparation

The need for a mechanical bowel preparation is controversial. Many surgeons continue to use mechanical bowel preparations despite the fact that a multiple of prospective randomized trials have now been done and suggest that its use does not decrease surgical site infections. At a minimum, the rectosigmoid needs to be cleared of fecal matter with enemas to facilitate bowel handling and most importantly to allow the passage of an intraluminal stapling instrument.

The use of oral antibiotics as part of the bowel preparation has been abandoned by many surgeons. Meta-analysis of multiple trials has suggested that the addition of oral antibiotics will lead to a lower incidence of surgical site infections.

The administration of intravenous antibiotics within 1 hour of incision time is well documented to decrease surgical site infections and should be given routinely.

Positioning

Following general endotracheal anesthesia, the patient should be placed in the dorsal lithotomy position (Fig. 55.1). The legs should be in stirrups that can be easily positioned and changed if need be. An indwelling Foley catheter is also placed as well as a gastric tube (oro or nasogastric). It is important to have the patient secured to the operating room table in some fashion to ensure that the patient does not move excessively when being placed in steep Trendelenburg during the procedure. Although some surgeons will use a bean bag apparatus for this purpose, any effective method such as taping or use of straps is acceptable. Having the ability to safely place the patient in steep Trendelenburg is essential to allow the small bowel move out of the operative field.

Trocar Placement

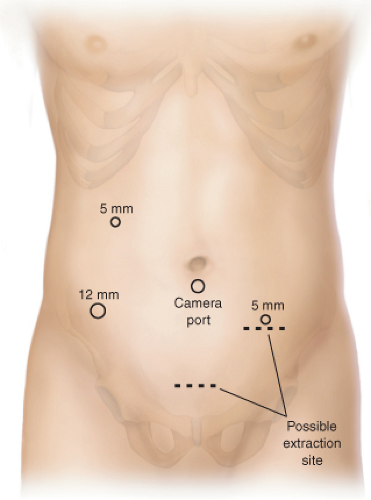

The placement of trocars is an important part of the success of this operation and is essentially the same as for sigmoid or left colectomies (Fig. 55.2). A periumbilical port

is used for the camera. Although usually the camera port is placed in an infraumbilical position, in a short patient with very little room between the pubis and the umbilicus, moving the port site to just above the umbilicus affords a better view with the laparoscope. Additional ports are placed as illustrated. The port in the right lower quadrant needs to be a 12-mm port to allow passage of an endoscopic linear stapler. The best rule for placement of this port is to place it 2 cm medial to and 2 cm superior to the anterior superior iliac spine. The other port on the right side can usually be a 5-mm port as this port is mostly used for passage of a grasper/dissector. An additional 5-mm port on the left side allows the assistant to provide retraction and countertraction for the primary surgeon.

is used for the camera. Although usually the camera port is placed in an infraumbilical position, in a short patient with very little room between the pubis and the umbilicus, moving the port site to just above the umbilicus affords a better view with the laparoscope. Additional ports are placed as illustrated. The port in the right lower quadrant needs to be a 12-mm port to allow passage of an endoscopic linear stapler. The best rule for placement of this port is to place it 2 cm medial to and 2 cm superior to the anterior superior iliac spine. The other port on the right side can usually be a 5-mm port as this port is mostly used for passage of a grasper/dissector. An additional 5-mm port on the left side allows the assistant to provide retraction and countertraction for the primary surgeon.

Vascular Division

Once all the trocars are in place, the patient is placed in steep Trendelenburg position to facilitate moving the small bowel out of the pelvis and thus optimizing the continued retraction of the small bowel. This simple maneuver will optimize visualization of the pelvic structures. The vascular division is done at the level of the superior hemorrhoidal vessels (Fig. 55.3) at the level of the sacral promontory. Dissection is most commonly undertaken in a medial to lateral fashion. The sigmoid colon is usually very redundant and the first step is to elevate the redundant colon out of the pelvis. By doing so, the superior hemorrhoidal vessels can be identified coursing over the sacral promontory. The mesentery can then be grasped and placed on traction. The simple step of placing the mesentery on tension makes the vasculature stand out even in the patient with a thick or very fatty mesentery (Fig. 55.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree