The role of laparoscopy in the case of nonpalpable cryptorchidism is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Laparoscopic orchiopexy for nonpalpable testes in the pediatric population has become the preferred surgical approach among pediatric urologists over the last 20 years. In contrast, laparoscopic varicocelectomy is considered one of several possible approaches to the treatment of a varicocele in an adolescent; however, it has many challengers and it has not gained universal acceptance as the gold standard. This article reviews the published evidence regarding these surgical techniques.

Key points

- •

Laparoscopy is the gold standard diagnostic modality for a nonpalpable testis.

- •

Once an abdominal testis is detected, one must determine whether the testis can be brought into the scrotum in 1 or 2 stages.

- •

There is controversy as to whether a testicular remnant should be excised and if a contralateral orchiopexy is needed.

- •

Indications for varicocelectomy in an adolescent are left testicular hypotrophy (>10%–20%), abnormal semen analysis or pain.

- •

Critics of the laparoscopic procedure have argued that this does not provide superior outcomes while introducing the significant risks to intra-abdominal contents associated with laparoscopy.

Introduction: laparoscopic orchiopexy – what is the advantage?

Unilateral or bilateral cryptorchidism is found in 4% of newborns and 0.8% to 2% of 1-year-old boys, and 20% to 35% of those are nonpalpable testes. A testis that has not descended by 6 months of age is unlikely to descend; therefore, surgery should be considered. The cryptorchid testis may be difficult to palpate in an awake and uncooperative child or an obese child with a large suprapubic fat pad. In rare instances, a sonogram may be helpful to plan the surgical approach but in general is of little to no value. A truly nonpalpable testis may represent an intra-abdominal undescended testis (vanishing testis), which is one that had atrophied before evaluation, or testicular agenesis/dysgenesis. The atrophic testis can be found in the scrotal position and is thought to be a prenatal event in a descended or descending testis. In that case, the internal ring is usually closed, and the testicular vessels are seen entering it, along with the vas deferens. It is common to palpate a testicular remnant (nubbin) in the upper scrotum. A vanishing testis may also be represented by blind-ending vessels in an intra-abdominal position. Early testicular atrophy is usually accompanied by contralateral testicular compensatory hypertrophy, a finding that provides a clue to the true diagnosis. Agenesis or dysgenesis of a testis is uncommon and may be associated with disordered sexual differentiation or even absence of the contralateral kidney.

A cryptorchid testis is at a higher risk (risk ratio, 2.5–8) of malignancy development than a scrotal testis. These patients have a slightly higher risk of testicular cancer in the contralateral testis as well. Orchiopexy before puberty may significantly decrease the risk of malignancy later in life. Additionally, there is an association between cryptorchidism and decreased fertility caused by testicular dysfunction, particularly in bilateral cases. An inguinal hernia is often associated with the undescended testis and is another cause for concern. Finally, testicular torsion would be difficult to diagnose in an abdominal testis and would increase the risk of testicular loss.

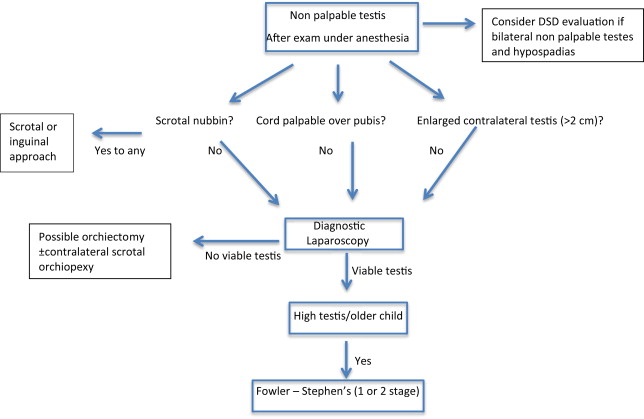

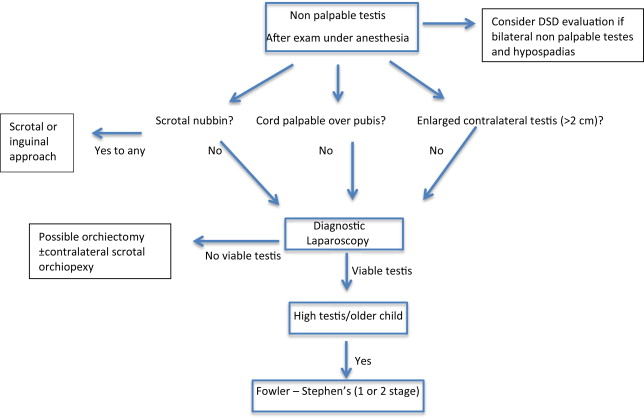

The role of laparoscopy in the management of a nonpalpable testicle is 2-fold. Diagnostic laparoscopy was first described by Cortesi in 1976, and has been accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of a nonpalpable testicle. The preferred method of treating an intra-abdominal testis is no longer controversial. The combined inguinal/retroperitoneal open approach has been largely replaced by laparoscopy, which was first described in the 1990s. In capable hands, the laparoscopic approach has equivalent or superior outcomes as the open one with regard to testicular viability and scrotal position. It also provides the advantages of the minimally invasive approach, with decreased postoperative pain and scarring. There is still debate regarding the need to divide the testicular vessels in high intra-abdominal testes (Fowler Stephen’s approach), and whether to do that in 1 or 2 stages.

Diagnostic laparoscopy may show the absence of one or both testes. A testicular nubbin can be excised via an open approach (scrotal or inguinal) and rarely laparoscopically. It is controversial whether it is necessary to remove a testicular nubbin, as it has not been associated with malignancy. The decision to perform a scrotal orchiopexy in the case of a solitary contralateral testis is one that should be made after discussion with the parents preoperatively and is based on the surgeon’s preference.

Cost analysis finds that the use of laparoscopy does not increase the cost of the procedure when compared with the open approach if it is done with reusable instrumentation and operating room time is low ( Fig. 1 ).

Introduction: laparoscopic orchiopexy – what is the advantage?

Unilateral or bilateral cryptorchidism is found in 4% of newborns and 0.8% to 2% of 1-year-old boys, and 20% to 35% of those are nonpalpable testes. A testis that has not descended by 6 months of age is unlikely to descend; therefore, surgery should be considered. The cryptorchid testis may be difficult to palpate in an awake and uncooperative child or an obese child with a large suprapubic fat pad. In rare instances, a sonogram may be helpful to plan the surgical approach but in general is of little to no value. A truly nonpalpable testis may represent an intra-abdominal undescended testis (vanishing testis), which is one that had atrophied before evaluation, or testicular agenesis/dysgenesis. The atrophic testis can be found in the scrotal position and is thought to be a prenatal event in a descended or descending testis. In that case, the internal ring is usually closed, and the testicular vessels are seen entering it, along with the vas deferens. It is common to palpate a testicular remnant (nubbin) in the upper scrotum. A vanishing testis may also be represented by blind-ending vessels in an intra-abdominal position. Early testicular atrophy is usually accompanied by contralateral testicular compensatory hypertrophy, a finding that provides a clue to the true diagnosis. Agenesis or dysgenesis of a testis is uncommon and may be associated with disordered sexual differentiation or even absence of the contralateral kidney.

A cryptorchid testis is at a higher risk (risk ratio, 2.5–8) of malignancy development than a scrotal testis. These patients have a slightly higher risk of testicular cancer in the contralateral testis as well. Orchiopexy before puberty may significantly decrease the risk of malignancy later in life. Additionally, there is an association between cryptorchidism and decreased fertility caused by testicular dysfunction, particularly in bilateral cases. An inguinal hernia is often associated with the undescended testis and is another cause for concern. Finally, testicular torsion would be difficult to diagnose in an abdominal testis and would increase the risk of testicular loss.

The role of laparoscopy in the management of a nonpalpable testicle is 2-fold. Diagnostic laparoscopy was first described by Cortesi in 1976, and has been accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of a nonpalpable testicle. The preferred method of treating an intra-abdominal testis is no longer controversial. The combined inguinal/retroperitoneal open approach has been largely replaced by laparoscopy, which was first described in the 1990s. In capable hands, the laparoscopic approach has equivalent or superior outcomes as the open one with regard to testicular viability and scrotal position. It also provides the advantages of the minimally invasive approach, with decreased postoperative pain and scarring. There is still debate regarding the need to divide the testicular vessels in high intra-abdominal testes (Fowler Stephen’s approach), and whether to do that in 1 or 2 stages.

Diagnostic laparoscopy may show the absence of one or both testes. A testicular nubbin can be excised via an open approach (scrotal or inguinal) and rarely laparoscopically. It is controversial whether it is necessary to remove a testicular nubbin, as it has not been associated with malignancy. The decision to perform a scrotal orchiopexy in the case of a solitary contralateral testis is one that should be made after discussion with the parents preoperatively and is based on the surgeon’s preference.

Cost analysis finds that the use of laparoscopy does not increase the cost of the procedure when compared with the open approach if it is done with reusable instrumentation and operating room time is low ( Fig. 1 ).

Indications

- •

A nonpalpable abdominal testis

- •

Recurrent iatrogenic cryptorchidism (redo orchiopexy)

- •

Option: High canalicular/peeping testes

- •

Unusual cases: bilateral orchiopexy, abdominal wall defects, polyorchidism, splenogonadal fusion, and transverse testicular ectopia

The most definitive method of evaluating and potentially treating a nonpalpable testis is laparoscopically, as imaging modalities have repeatedly show low sensitivity and specificity for accurately locating an undescended testicle. A physical examination performed by a trained specialist of a nonobese child, awake or under anesthesia, is highly accurate in differentiating a palpable versus a nonpalpable testis. Once the testis is determined to be nonpalpable, a diagnostic laparoscopy is performed to identify its location and viability.

A laparoscopic approach is also possible in cases in which the initial orchiopexy failed to result in a scrotal position of the testis. A reoperative inguinal approach to a recurrent undescended testis may be limited by scarring and inability to gain additional length through a groin incision. The laparoscopic approach provides the benefit of accessing virginal tissues with the potential of mobilizing the testicular vessels proximally.

The use of laparoscopy in palpable inguinal testes has been examined. He and colleagues and Riquelme and colleagues reported on a series of 103 and 30 testes, respectively, in which they used laparoscopy in the management of palpable canalicular testes with success rates equivalent to an open technique and with the advantages of laparoscopy.

Procedure

Positioning

- •

Position the patient at the end of the table, as the child is typically young and their torso is short, so the surgeon will be at the upper portion of the table facing the patient’s feet and on the left of the patient (if right handed).

- •

Do not elevate the pelvis with a rolled towel, as that will decrease the intra-abdominal working space.

Preparation

- •

Prepare from xiphoid to the midthighs.

- •

Catheterize the bladder on the field with a feeding tube.

Detailed Steps

- •

Place a camera port at the umbilicus.

- •

Inspect the abdomen. Abort the case if a testis is not found intra-abdominally. A nubbin may be excised at this time.

- •

Look for a vas if the testis is not readily identified. In some instances, the testis may be deep in the pelvis, and looking for the vas at the takeoff of the seminal vesicles will lead to identification of the testicle.

- •

Add 2 lateral ports if a viable testis is found. Consider using a 5-mm port for the camera. This will come in handy later to pass a 5-mm trocar through the scrotum ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2

Trocar placement.

- •

For a peeping testis, place traction on the testis itself and do not handle the epididymis ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3

Traction on the testicle to transect the gubernaculum.

- •

Ensure that the epididymis and vas do not loop into the inguinal canal (if you cannot be sure that the epididymis and vas are safe, do not hesitate to make a groin incision at this point if needed).

- •

If the vas and epididymis are clear, transect the gubernaculum (if it bleeds you likely cut the epididymis and not pure gubernaculum).

- •

Lift the peritoneum and dissect medially over the median umbilical ligament and then lift the peritoneum off the bladder, leaving a cuff of peritoneum away from the vas ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4

Peritoneal cuff preserved in a Fowler-Stephens case.

- •

Make the lateral wall dissection as high as possible along the lateral edge of the psoas ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5

Peritoneal edge.

- •

Come across the peritoneum over the gonadal vessels at this point (trying to free the peritoneum when the testis is on tension leads to a high probability that the gonadal vessels will be inadvertently transected, potentially leading to delayed bleeding).

- •

Continue the dissection down the peritoneum to the root of the small bowel mesentery.

- •

Mobilize the bladder off the pubic bone medial to the median umbilical ligament (ensure that the feeding tube is in the bladder and the bladder is empty).

- •

Use a dissector (Maryland) to push over the pubic bone while inverting the scrotum, and feel for the thinnest area, which is the external inguinal ring.

- •

Push the dissector through the anterior abdominal wall (a pop will be felt).

- •

Make an incision in the scrotum and create the subdartos pouch.

- •

Push the dissector through the scrotal incision and back load a 5-mm trocar over the dissector and push into the abdomen ( Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6

Dissector placed through the neo-canal.

- •

Use a toothed grasper and bring this through the 5-mm trocar and hand the testis to the toothed grasper with the other hand. (Make sure that the testis is grasped and not the epididymis or vas.)

- •

Bring the testis through the neo-canal. (Pull the testis into the trocar as far as possible; this will make the testis more elliptical and will facilitate the removal of the testis through the canal.)

- •

As soon as the testis is in the field, grab the testis with a toothed forceps and then place your anchoring sutures.

- •

Deflate the abdomen at this time and check the testis position. (With the abdomen inflated, the testis typically will sit much higher in the scrotum.)

- •

If there is not enough length and the testis is in an unsatisfactory position, a Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy can be performed at this time.

- •

A clip applier can be brought into the field and the vessels clipped and transected.

- •

Once the testis has been anchored with the abdomen deflated, reinflate the abdomen and inspect for bleeding that may have occurred. Make sure that the ureters have not been elevated or kinked ( Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 7

Testis exiting new ring.

- •

Close each trocar port.

Complications and management

- •

Testicular atrophy

- •

Recurrence

- •

Vascular injury

- •

Bladder injury

Testicular Atrophy

- •

Atrophy may be evident on physical examination at the second postoperative visit, generally 6 months after the procedure, but in some instances it may not be evident until 1 year from surgery. Some have advocated the use of a sonogram to confirm testicular viability, but in prepubertal testes it can be difficult to get good flow curves, and the delayed examination 1 year or later is the best test for viability. The risk of atrophy, which is irreversible, drives many practitioners to approach bilateral orchiopexy in a staged approach.

- •

Single-stage Fowler-Stephen’s orchiopexy has the highest rate of atrophy (3%–22%), whereas a vessel-sparing procedure had the lowest atrophy rates (0%–4%).

- •

A long looping vas was found to be a risk factor for testicular atrophy in cases of laparoscopic second-stage orchiopexy, presumably because of inability to preserve collateral vassal blood supply adequately.

Recurrent Cryptorchidism

- •

This complication, which is reported in 0% to 19% of laparoscopic orchiopexy series is caused by insufficient mobilization of the testis or inadequate testicular fixation and often requires a secondary procedure. This procedure should be attempted at least 6 to 12 months after the initial procedure to allow for maximal healing and possible testicular descent in the interim.

Bladder Injury

- •

This injury occurs during the creation of the transperitoneal tunnel for the undescended testis between the bladder and the obliterated umbilical ligament. It may result in significant morbidity if it is not identified intraoperatively; therefore, one must maintain a high index of suspicion.

- •

This risk may be minimized by emptying the bladder before the creation of the tunnel and aspiration of the bladder. It is also helpful to perform extensive dissection lateral to the bladder to enable visualization of the bladder edge.

- •

This injury should be suspected when there is difficulty creating the tunnel or any degree of hematuria is present; however, hematuria may be absent in some cases. Cystoscopy should be performed to confirm the injury. Alternatively, if the diagnosis is delayed, a cystogram can provide the diagnostic information.

- •

Management of this transperitoneal injury requires bladder repair, which can be done laparoscopically, depending on the practitioner’s level of confidence. The bladder must be decompressed with a catheter after the repair to facilitate recovery; however, the duration is not agreed upon.

Vascular Injury

- •

Injury to the femoral vessels during passage of the dissector into the scrotum is a potentially catastrophic event. This event can be reliably avoided by creating the neo-canal from lateral to medial and by dissection of the space between the bladder and the obliterated umbilical vessels down to the pubic bone in preparation for the blind advancement of the dissector.

- •

Injury to iliac vessels during laparoscopic mobilization of the testis

- •

Inadvertent avulsion of the testicular vessels during delivery of the testis into the scrotum may be caused by excessive traction on the testis when at the time the surgeon is focused on the scrotal aspect of the procedure and does not have intra-abdominal visualization. Furthermore, the vessels may have been avulsed but in spasm, making recognition of this injury more difficult. Therefore, it is advised to incise the peritoneum before delivering the testis, as injury to the vessels will be readily evident. It is recommended that the surgeon, not the assistant, be the person holding the testis when the testis is on traction and dissection of the vessels is occurring, because they can feel the tension in the cord structure during the dissection. It is important to have a high level of suspicion for such a complication to address it intraoperatively by controlling the vessels.

Complications associated with laparoscopy are rare but must be discussed (hypercapnia, injury to intra-abdominal organs, port site hernia, delayed bowel obstruction caused by adhesions).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree