Laparoscopic Incisional and Ventral Hernia Repair

Karl A. LeBlanc

In general, a laparoscopic repair of an incisional or ventral hernia (LIVH) can be considered for any individual who is stable enough to undergo a general anesthetic. The majority of these patients will have developed a hernia following an open intraabdominal procedure or will have had one or more failed hernia repairs by either the open or laparoscopic method. The indications most commonly used are as follows:

Fascial defect size >3 to 4 cm in a non-obese patient

Fascial defect ≥2 cm in obese patients

Recurrent hernias with or without multiple defects

Most patients will fit into one of the above categories, however, there are circumstances that need to be considered wherein an open procedure might be the better option such as:

Infected or exposed mesh

Thin skin with direct adherence to the underlying intestine

Hernias larger than 15 cm in transverse dimension

Unusual locations such as a “denervation” flank hernia (although a combined approach can be used)

Extremely extensive intraabdominal adhesions

Exposed or infected mesh will need excision and other therapy to close the defect that cannot be effectively dealt with by the laparoscopic approach. The second situation may have resulted in vascular supply to the overlying skin by the intestine (as prior open abdomen with skin graft) resulting in skin necrosis with dissection of the underlying adherent intestine for the repair. Very large hernias will require component separation. The hernias that commonly develop after nephrectomy result from transection of the innervation to the abdominal wall muscles. This will not provide an acceptable cosmetic result in most patients (but a combination of open and laparoscopic approach can be applied successfully). The last consideration is based upon time factors. If the laparoscopic adhesiolysis will incur operative times of 3 to 4 hours alone, then an open

approach will likely be quicker; however, here again, a hybrid approach could be applied.

approach will likely be quicker; however, here again, a hybrid approach could be applied.

In most patients, routine laboratory testing as per their age and co-morbidities will be sufficient. Elderly patients or those with significant heart or lung disease may be at risk for an inability to tolerate the required insufflation pressures. They may require preoperative cardiac and pulmonary assessments. It is preferable for the morbidly obese patient to lose 10% to 15% of their weight preoperatively. This will aid in the repair and significantly improve the available intraabdominal space with which to perform the repair. In patients with prior abdominal procedures, especially if these were hernia repairs with mesh, it is beneficial to obtain the operative reports from the prior surgical procedures (when possible).

A CT scan is helpful in most cases but is not always necessary. It is especially useful for large, multiple or unusually located hernias. In some cases, a previously placed mesh and/or tacks used for fixation may be seen. This will assist in planning the procedure. If performed, this should be done with oral contrast to identify any intestinal contents within the hernia.

All patients should not be nutritionally depleted. All patients who smoke should cease for at least 3 to 4 weeks prior to the operation to diminish complications such as wound infection. If there has been a prior mesh infection, it is desirable to delay the repair for 3 to 6 months to ensure adequate clearance of any bacteria. Additionally, one should then use prophylactic antibiotics specifically used for the prior bacterial infection as these pose a particularly high risk. The use of purgatives is not necessary unless the colon is located within the hernia contents.

LIVH procedures will begin the introduction of general anesthesia. Nasogastric suction is used selectively. If the procedure is felt to be relatively uncomplicated and short in duration, a urinary drainage catheter is unnecessary. If the location of the hernia is in the lower portions of the abdomen, a three-way catheter should be used. The bladder can be filled with saline to ease its identification for dissection and placement of transfascial sutures. Sequential compression devices should be used because of the nature of these operations. Prophylactic anticoagulation should be considered as well.

Positioning

The supine position will be used in the majority of these cases. However, if the hernia is located in the flank, lumbar, or other areas the patient will require positioning on their side at least to some extent. A “bean-bag” for this purpose is very supportive. If the hernia is the upper abdomen, the arms do not need to be tucked. It is preferable (if the habitus of the patient allows) to tuck them for hernias in the lower abdomen for technical maneuvers related to the procedure. After widely draping the patient, an iodine impregnated plastic drape should be used over the skin.

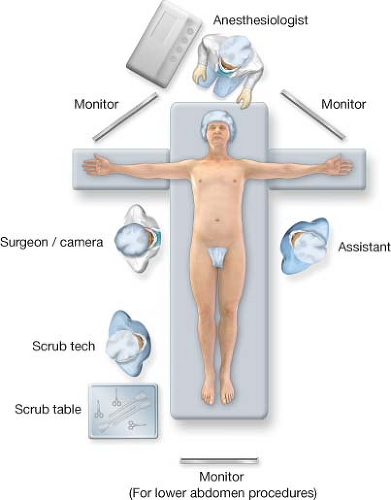

The monitors that are used for any laparoscopic operation should be placed so that the surgeon is looking directly into them with no strain on the neck of the operator. This is an ergonomic consideration that is frequently forgotten. There should be one on either side of the table for all of the participants of the procedure to visualize (Fig. 32.1). The operating table should be able to assume Trendelenberg (and reverse) positions as well as roll side to side (airplane maneuver).

Technique

There are several steps to the operation:

Access to the abdominal cavity

Laparoscopic selection

Methods and instruments of adhesiolysis

Identification and measurement of the defect(s)

Potential of defect closure

Choice and introduction of the prosthetic material to repair the hernia

Fixation of the product

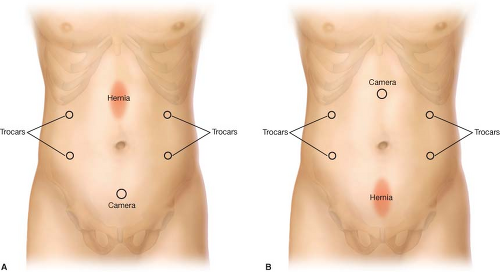

The initial consideration with all laparoscopic procedures should be the method and location of the entry into the abdominal cavity. All methods are applicable to LIVH. Most surgeons prefer the subcostal regions for the initial entry regardless of technique. If there is a hernia in these regions or if the trocar placement in that location is not appropriate, other sites will be used. Generally, three to four trocars will be used. I believe it best to place at least one trocar on the opposite side of the abdomen to adequately visualize the contents of the abdomen during dissection and fixation (Fig. 32.2). After the introduction of each successive trocar, the laparoscope should be inserted to view the areas from that perspective to assure the locations of the intestine and the adhesions.

Currently, the use of 5 mm laparoscopes is most common. However, if the optics are not best, the 10 m scopes would be needed. The latter scopes are able to withstand more torque than their smaller counterparts. Most surgeons will use the 30° scopes but many prefer the 0° while the 45° can occasionally be useful.

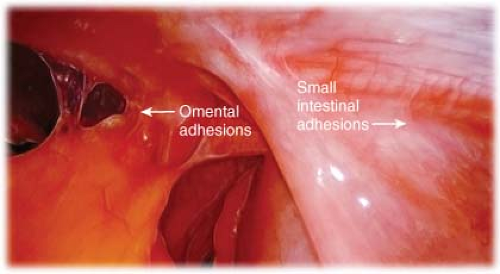

Without question, the lysis of the adhesions of these individuals can be the most challenging portion of the operation and constitutes the largest segment of time involved (Fig. 32.3). The options include blunt dissection, cold or hot scissor dissection, bipolar cautery, or ultrasonic dissection. Blunt dissection is better suited with filmy adhesions. Cold scissor dissection should be used in close proximity of the intestine. The latter

three options are very helpful when omental or vascularized adhesions require lysis. In all cases, one should be as certain as feasible that there is no bowel adjacent to the areas where these are used to avoid injury.

three options are very helpful when omental or vascularized adhesions require lysis. In all cases, one should be as certain as feasible that there is no bowel adjacent to the areas where these are used to avoid injury.

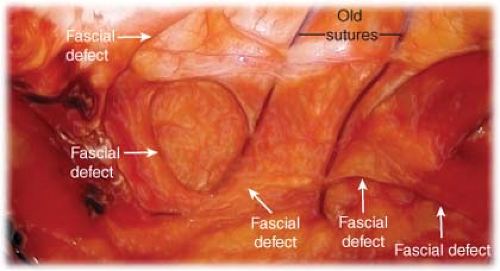

Once all of the adhesiolysis has been completed, all of the fascial defects should be identified (Fig. 32.4). It is important to perform wide dissection including the preperitoneal fat that will prevent the prosthesis from contacting the fascia into which it must attach. It is especially important in the upper abdomen to dissect the falciform ligament away from the fascia such that there can be a 5 to 8 cm overlap of the mesh in this area if there is a subxyphoid hernia (Fig. 32.5). Similarly, in the pelvis, the bladder must be brought down to expose Cooper’s ligament so that the mesh can be fixed to that structure if the hernia is suprapubic (Fig. 32.6). There are a multitude of options of measurement of the defect(s). Sizing can be difficult in a fully insufflated abdomen; therefore, in most instances all of the carbon dioxide should be released for measurement. I prefer to place marks at the four cardinal points of the defect(s) with the fully inflated abdomen (Fig. 32.7), then measuring once all of the CO2 is released

(Fig. 32.8). If multiple defects are present, one should measure from the farthest apart margins in all directions. Additionally, one should provide mesh coverage under all of the existing incision to mitigate future development of hernias at a site not covered by the prosthesis.

(Fig. 32.8). If multiple defects are present, one should measure from the farthest apart margins in all directions. Additionally, one should provide mesh coverage under all of the existing incision to mitigate future development of hernias at a site not covered by the prosthesis.

Figure 32.5 Fully dissected falciform ligament. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree