If the child in question, whose pretest likelihood of celiac disease is estimated to be 8%, has a negative test it may be concluded that the child almost certainly does not have celiac disease; on the other hand, if the child has a positive test, the likelihood of him or her having celiac disease is still only 65%.

As Gregor and Alidina point out, the implications of misdiagnosis must be considered carefully. In the circumstance of a positive test in the child with non-specific symptoms the physician and the child’s parents should consider whether it is now reasonable to proceed to intestinal biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, rather than recommending a gluten-free diet, presumably for life. If a search for other clinical or laboratory clues reveals that celiac disease is very likely to be the correct diagnosis, the pretest likelihood may be as high as 50%. This would raise the post-test likelihood to 97%. The physician and parents may be comfortable accepting the diagnosis and proceed to a trial of a gluten-free diet, rather than subjecting a young child to intestinal biopsy. This is an excellent example of how a skilled clinician must integrate the principles of evidence-based medicine with traditional clinical skills and judgment.

Table 1.1 The anti-endomysial antibody (EMA) test for celiac disease. Dependence of post-test likelihood of celiac disease on pretest likelihood, assuming positive LR = 31, negative LR = 0.06.

| Pretest likelihood of celiac disease | Post – test likelihood with a positive EMA test (%) | Post – test likelihood with a negative EMA test (%) |

| 8% (non – specific symptoms, positive family history | 65 | 0.5 |

| 50% (more specific symptoms) | 97 | 6 |

| 0.25% (population screen) | 8 | 0.02 |

Data from Chapter 10.

Offering a prognosis

Example: A 50-year-old woman with recently diagnosed celiac disease. has learned at a meeting of the local celiac society that patients with celiac disease have a substantial increase in the risk of developing a number of cancers and that this cancer risk is reduced by strict adherence to a gluten-free diet.

Chapter 10 describes the types of study which are relevant to determination of prognosis and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of case-control and cohort studies.

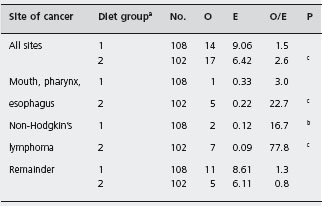

Gregor and Alidina point out that certain case-control studies which reported very high mortality and malignancy rates may have been subject to selection bias (inclusion of particularly ill or refractory patients) and measurement bias (patients with abdominal symptoms being more likely to undergo investigations such as small bowel biopsy which may lead to a diagnosis of celiac disease). They refer to a British study in which a cohort of patients with celiac disease was assembled and followed for ten years. This design attempts to minimize the biases that are inherent in the case-control studies. Table 1.2 shows that the risk of certain cancers is increased compared to the risk in the general population. Table 1.3 shows that strict adherence to a gluten-free diet significantly reduced this risk and may have eliminated the excess risk for several of the identified cancers.

Table 1.2 Cancer mortality in 210 patients with celiac disease at the end of 1985.

Source : Holmes GKT et al. Gut 1989; 30 : 333 – 338 [25].

ap < 0.01.

bp < 0.01.

O: observed numbers; E: expected numbers.

On the basis of this evidence it is reasonable to advise the patient that her disease does carry with it an increased risk of certain relatively uncommon cancers and that adherence to a strict gluten-free diet appears to minimize this increased risk.

Recommendations concerning therapy

We have provided examples of how evidence concerning the use of diagnostic tests and prognosis can be analyzed and incorporated into clinical practice. Most chapters in this book deal more extensively with evidence concerning therapy and rely heavily on data from randomized trials and meta-analyses.

Example: Should a 28-year-old woman who has had an uncomplicated resection of the terminal ileum for Crohn’s disease receive maintenance therapy with an S-aminosalicylate (ASA) product? Prior to the surgery she had had steroid-dependent disease and had failed treatment with both azathioprine and methotrexate.

A search of the literature for placebo-controlled randomized trials of 5-ASA for maintenance of remission in patients with a surgically induced remission of disease would reveal several trials. The largest published trial is that of McLeod and colleagues, who randomized 163 adult patients to receive either 3 g/day of 5-ASA or a placebo following surgery [26]. The primary outcome of interest was the recurrence of active Crohn’s disease as defined by the recurrence of symptoms and the documentation of active disease either radiologically or endoscopically. At the end of the follow-up period (maximum duration 72 months, median duration 34 months), 31% of patients who received active treatment remained in remission compared with 41% of those who received a placebo (p = 0.031); 5-ASA was well tolerated. A low proportion of patients developed adverse reactions in the control and active treatment groups. One patient treated with 5-ASA developed pancreatitis that was attributed to the study drug. The results of this study can be evaluated using the guidelines described in Figure 1.2, which is modeled after the approach of Kitching et al. [24].

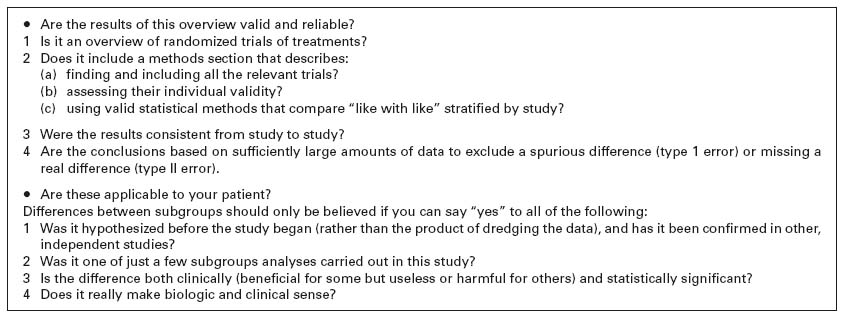

a Diet group 1, strict adherence to gluten-free diet; group 2, reduced gluten diet or normal diet. Source: Holmes G KT et al. Gut 1989; 30: 333-338 [25].

bp < 0-01.

cp < 0.001

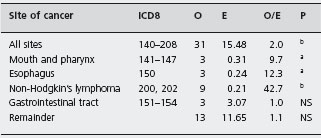

Are the results of this study valid?

A review of the methods section of the article confirms that an appropriate method of randomization was employed (computer-generated in permutated blocks), which insured concealment of the randomization code [26]. Furthermore, inspection of the baseline characteristics of the treatment and control groups shows that they are well balanced with respect to such confounding variables as the time from surgery to randomization. This information further supports the legitimacy of the randomization process. Assessment of the method of randomization is important, because non-randomized designs are especially vulnerable to the effects of bias. Studies which employ “quasi-randomization” schemes such as allocation to treatment according to the day of the week or alphabetically by the patient’s surname have been shown to consistently overestimate the treatment effect identified by RCTs that employ a valid randomization scheme [27, 28]. However, it may be noted that 87 patients were randomized to 5-ASA, compared with only 76 patients in the control group. This observation raises the concern that the analysis might not have been done according to the “intent to treat” principle which specifies that patients are analyzed in the group to which they were originally assigned, irrespective of the treatment that was ultimately received. The use of this strategy reduces the possibility of bias, which might occur if investigators selectively withdrew from the analysis patients who had done poorly or experienced toxicity. For this reason, the intent to treat principle yields a conservative estimate of the true benefit of the treatment. However, detailed review shows that in this study the discrepancy in patient numbers occurred because five patients who were randomized to the active treatment group withdrew consent prior to receiving the study medication and were not included. Thus, it appears that the analysis was based on the intent to treat principle.

Approximately 10% of patients in both treatment groups had incomplete follow-up. Methodologically rigorous studies have a very low proportion of patients for whom data are missing. This issue is important, since patients who are lost to follow-up usually have a different prognosis from those for whom complete information is available. If there is incomplete follow-up data for a substantial proportion of patients then the results are uninterpretable [29].

Turning to an assessment of the outcomes in this study, both the patients and investigators were unaware of the treatment allocation. Blinding is used to reduce bias in the interpretation of outcomes. This is especially important when a subjective outcome is evaluated [30]. In this study, objective demonstration of recurrent disease (endoscopy and/or radiology) was required in addition to the more subjective measure of the introduction of treatment for recurrent symptoms. Thus, the reader can be satisfied that the primary outcome measure was both clinically meaningful and objectively assessed.

Finally, the data analysis and results should be examined. A great deal of useful information can be obtained by reviewing the assumptions that were used in the sample size calculation. In this study, which analyzes a difference in proportions, the investigators had to define four variables: the alpha (type 1) error rate, the beta (type 2) error rate, the expected proportion of patients who would be expected to relapse in the placebo group, and the minimum difference in the rate of relapse which the investigator wished to detect. In this publication these parameters are easily identified. The rate of symptomatic recurrence was estimated to be 12.5% per year and it was anticipated that treatment with 5-ASA would reduce this rate by 50% to an absolute value of 6.25% per year. In contrast to the expected 50% relative risk reduction which was anticipated, the three-year actuarial risk of recurrence was 26% in the treatment group compared to 45% in the group that received 5-ASA (p = 0.039). Therefore, the relative risk reduction ((45–26%)/45% = 42%) is slightly lower than the figure which the investigators considered to be clinically meaningful. Furthermore, the probability of a type 1 error is described as a one-tailed value of p = 0.05. This implies that one-tailed statistical testing was used to derive the p value of 0.039. The use of one-sided statistical testing raises legitimate concerns regarding the statistical inferences made in the study [31]. It is inappropriate to hypothesize that 5-ASA therapy could only be beneficial, given that the drug can cause diarrhea and colitis [32]. For these reasons, uncertainty exists regarding both the clinical and statistical interpretation of these data.

Are the results of this valid study important?

To assess the importance of this result it is necessary to quantify the magnitude of the treatment effect. How the evidence is presented may influence both physicians and patients in making choices. The most basic means of expressing the magnitude of a treatment of fact is the absolute risk reduction (ARR), which is defined as the proportion of patients in the experimental group with a treatment success minus the proportion of patients with this outcome in the control group. In this instance the annual rate of relapse in the placebo-treated patients was 15% (success rate of 85%) compared with 8.7% (success rate of 91.3%) in those who received the active treatment. This yields an ARR of 6.3%. The number needed to treat (NNT), the number of patients with Crohn’s disease who would have to be treated with 3 g/day of 5-ASA to maintain remission over a year, can be calculated as the reciprocal of this number, and is 16. Alternative ways of describing effectiveness include calculating the observed relative risk reduction (RRR = 63/15) of 42%, or even stating that about 90% of patients respond to maintenance therapy, ignoring the substantial placebo effect which is evident. The evidence presented as the ARR or NNT, rather than the numbers which show the treatment in a more favorable light, may still lead the physician to recommend this form of treatment and cause the patient to choose to accept this strategy over no intervention. However, the expectations of the physician and patients are likely to be more realistic than they may be if the physician accepts and promotes in an uncritical way the information that 90% of patients who receive 5-ASA maintenance therapy will remain in remission over one year [33].

Are these results applicable to my patient?

Following an assessment of the validity of the evidence using the criteria described in the preceding paragraphs, it is necessary to decide whether the conclusions of the study are relevant and important to the individual patient. An initial step is to evaluate the demographic characteristics of the patients in the RCT and compare them to those of the patient in question. If the patient for whom maintenance therapy is being considered is similar to the patients who were evaluated in the trial, it is reasonable to assume that she will experience the same benefit of therapy and is at no greater risk for the development of adverse drug reactions. Alternatively, this patient may have characteristics that make it unlikely that a benefit from 5-ASA will be realized. For example, if the patient had residual active Crohn’s disease it would be difficult to generalize the results of the study of McLeod et al., since the patients in this trial had resection of all visible disease prior to study entry [26].

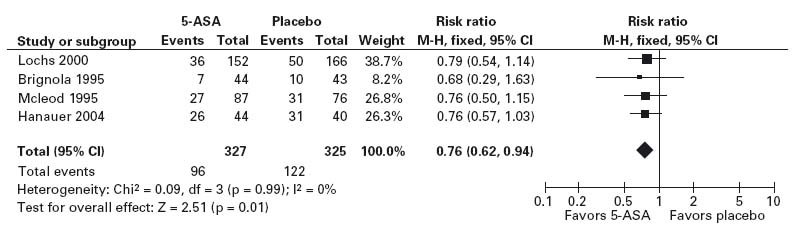

Source: Doherty G, Bennett G, Patil S, Cheifetz A, Moss AC. Interventions for prevention of post-operative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD006873. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006873.pub2.

At this point, if we accept that the results are generaliz-able to our patient example, the relative risks and benefits of the therapy must be weighed and the patient’s preferences should be considered. Evaluation of the data reveals that the trial was methodologically rigorous and evaluated an important outcome. However, it is doubtful whether conventional statistical significance was demonstrated. This raises the question of whether the observed differences between the treatment groups might have occurred by chance. Furthermore, the magnitude of the treatment effect is relatively small. In presenting to the patient the benefit of an annual reduction in the risk of recurrence of 6.3% it is also necessary to consider the cost and inconvenience of taking medication for an asymptomatic condition. One observation in favor of recommending the treatment is that the risk of serious toxicity with 5-ASA appears to be low.

Because there is a degree of uncertainty concerning the true benefit of 5-ASA maintenance therapy based on analysis of this single RCT, it would be prudent to review additional published data. A meta-analysis of 5-ASA therapy has been published [34]. Meta-analysis, the process of combining the results of multiple RCTs using quantitative methods, is an important tool for the practitioner of EBM. Pooling the results of multiple RCTs increases statistical power and thus may resolve the contradictory results of individual studies. Combining data from RCTs statistically also increases the precision of the estimate of a treatment effect. Moreover, the greater statistical power afforded by meta-analysis may allow insight into the benefits of treatment for specific subgroups of patients. These properties are particularly relevant to the case under consideration, given the previously identified concerns.

The meta-analysis summarized data from 15 RCTs which evaluated the efficacy of 5-ASA maintenance therapy in 1371 patients with quiescent Crohn’s disease. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either 5-ASA or placebo for treatment periods of 4–48 months. Although 5-ASA was superior to placebo in 13 of the 15 studies, the results of only two trials were statistically significant. Separate analyses were done using data from the four trials that included patients with a surgically induced remission (see Figure 1.3) in distinction to those that evaluated patients after a medically induced remission. Sensitivity analyses assessed the response to therapy in specific subgroups of patients. The overall analysis concluded that 5-ASA has a statistically significant benefit; the risk of symptomatic relapse in patients who received 5-ASA was reduced by 6.3% (95% confidence interval –10.4% to –2.1%, 2 p = 0.0028), which corresponds to an NNT of 16. Importantly, the greatest benefit was observed in the four trials that evaluated patients following a surgical resection. In these studies there was a 13.1% reduction in the risk of a relapse (95% CI: –21.8 – –4.5%, 2 p = 0.0028), which corresponds to an NNT of 8. No statistically significant effect was demonstrable in the analysis, which was restricted to the patients with medically induced remission.

Are the results of this meta-analysis valid and reliable?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree