The estimated population of the world in 2008 was 6.75 billion people, increasing by around 79 million people each year. The world population is aging. In 1970, the world median age was 22 years; it is projected to reach 38 years by 2050. The number of people in the world aged 60 years and older is expected to almost triple to 2 billion by 2050. Because cancer, especially prostate cancer, is predominantly a disease of the elderly, increases in the number of older people will lead to more cases of cancer, even if current incidence rates remain the same.

Key points

- •

Because cancer, especially prostate cancer (PC), is predominantly a disease of the elderly, increases in the number of older people will inevitably lead to more cases of cancer.

- •

The worldwide variable relation between prostate cancer mortality and life expectancy points toward racial and dietary influences on the occurrence and characteristics of prostate cancer.

- •

Contradictory study results are the basis of a still-ongoing debate on whether or not prostate-specific antigen (PSA)–based screening should be offered, which has led to many different guidelines worldwide.

- •

The PSA test has remarkable features as a screening test (easy to implement, reliable, cheap, capable of risk stratifying men at very low risk), but it is unable to identify men at moderate or high risk of having PC and having a potentially indolent and aggressive PC.

- •

Worldwide, further research on refining PSA-based algorithms, dealing with overdiagnosis, developing and validating more specific biomarkers, and exploring the role of imaging are ongoing; it is hoped that it will lead to an acceptable prostate cancer screening algorithm.

Introduction

The estimated population of the world in 2008 was 6.75 billion people, increasing by around 79 million people each year. The world population is aging. In 1970, the world median age was 22 years; and it is projected to reach 38 years by 2050. The number of people in the world aged 60 years and older is expected to almost triple to 2 billion by 2050. Because cancer, especially prostate cancer, is predominantly a disease of the elderly, increases in the number of older people will inevitably lead to more cases of cancer, even if current incidence rates remain the same.

Introduction

The estimated population of the world in 2008 was 6.75 billion people, increasing by around 79 million people each year. The world population is aging. In 1970, the world median age was 22 years; and it is projected to reach 38 years by 2050. The number of people in the world aged 60 years and older is expected to almost triple to 2 billion by 2050. Because cancer, especially prostate cancer, is predominantly a disease of the elderly, increases in the number of older people will inevitably lead to more cases of cancer, even if current incidence rates remain the same.

Prostate cancer and life expectancy

As early as in 1898, Alberran and Hallé noted the presence of a substantial number of prostate cancers in asymptomatic men. In 1954, Franks described that, in a UK population of men older than 50 years, about 38% harbored a “latent” prostate cancer; already at that time it was mentioned that the observed increase in incidence was caused by lengthening of longevity from 46.6 years in 1911 to 67 years in 1947.

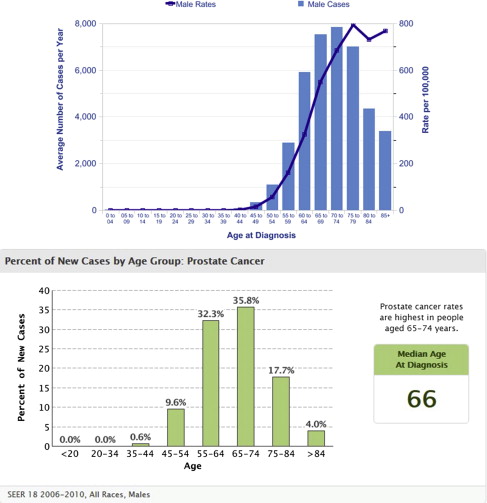

Incidence data of prostate cancer per age group for Europe (United Kingdom) and the United States are shown in Fig. 1 and confirm these early figures; prostate cancer is a disease of the elderly and, hence, will form a potential health problem for those countries where the life expectancy is relatively high (ie, >70 years).

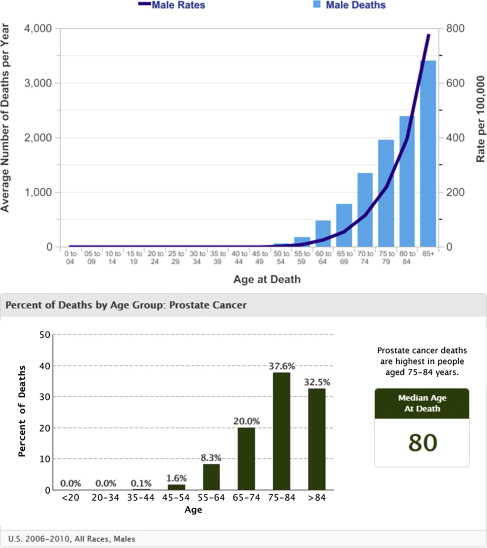

Similar data are available for prostate cancer mortality ( Fig. 2 ). These observations are confirmed when looking at the worldwide distribution of deaths caused by prostate cancer. In 2008, approximately 258,000 men died of prostate cancer, with more than half of these deaths occurring in the developed world.

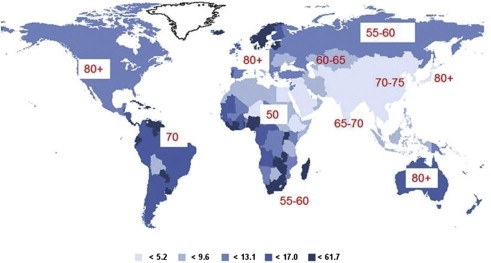

The relation between life expectancy and age-standardized prostate cancer mortality rates is displayed in Fig. 3 . Remarkable are the Asian and African continent where, in the Asian countries, despite a high life expectancy, the prostate cancer mortality rates are relatively low. It must be noted, however, that the most recent data show an increase. In the African continent, the opposite is true; life expectancy is relatively low, whereas prostate cancer mortality is one of the highest in the world. These observations point toward racial and dietary influences on the occurrence and characteristics of prostate cancer. In addition, the availability of structured health care may also play a role.

Randomized prostate cancer screening trials

When looking at Fig. 3 , it is not surprising that studies with the goal to investigate whether population-based screening could reduce prostate cancer–specific mortality were initiated in the United States and Europe. Both trials, the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) in Europe and the prostate arm of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) in the United States, reported their results on mortality outcomes in 2009 and 2012. Remarkably, the results were contradictory. Although the European trial showed a statistically significant relative reduction of 20% in favor of screening, the US trial showed no effect on disease-specific mortality. It is currently generally accepted that the outcome of both trials, being very different in design and conduct, cannot be compared directly. The ERSPC shows an effect of systematic, strictly protocol, prostate-specific antigen (PSA)–based screening versus no screening, whereas the PLCO shows PSA-based screening according to a protocol but with the possibility of including clinical judgment versus a control arm where opportunistic screening was very common. Despite these fundamental differences in design both trials, and with the inclusion of smaller (randomized) trials studying the effect of (PSA-based) prostate cancer screening on prostate cancer (PC) mortality, meta-analyses have been performed, which, as can be expected, have been heavily criticized.

Next to the randomized prospective trials, modeling studies have been initiated to circumvent the current lack of follow-up and restrictions with respect to sample size. Based on the empiric screening data and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry data in the United States, it has been estimated that screening results in a considerable percentage of overdiagnosed cases (between 15% and 37%). The models projected that 45% to 70% of the observed decline in PC mortality in the United States could be plausibly attributed to the stage shift induced by screening. More recent data showed that changes in primary treatment explained 22% to 33% of the observed decline in prostate cancer mortality. The remainder of the decline probably was because of other interventions, such as advances in the treatment of recurrent and progressive disease. When extrapolating the ERSPC mortality reduction to the long-term US setting, it was estimated that the absolute mortality reduction is at least 5 times greater than that observed in the trial with a median follow-up of only 11 years.

Modeling studies can also be used to predict potential harms and benefits of different screening policies. Although the data clearly indicate that PSA screening strategies that use higher thresholds for biopsy referral for older men or screen men with low PSA levels less frequently lead to a reduction in harms, the fact that mortality reduction as compared with more aggressive screening policies is also lowered (although sometimes marginally) further drives uncertainty and debate.

Guidelines on prostate cancer screening

These contradictory and, thus, confusing findings are the basis of a still-ongoing debate on whether or not PSA-based screening should be offered either in the setting of clinical practice (early detection) or in a structured population-based program (screening). This debate has led to many different guidelines worldwide ( Table 1 , adapted/updated from ).

| Guideline Group | Recommendation | Age to Begin | Interval/Algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| US Preventive Services Task Force | Recommends against screening (grade D) | — | — |

| American Cancer Society | Informed decision making | Begin PSA testing at 40 y if at highest risk (several first-degree relatives diagnosed with prostate cancer <65 y). Begin at 45 y for men at high risk (African American men and/or men with a first-degree relative). “Begin at age 50 for men at average risk and with a life-expectancy >10 y.” | “Men who choose to be tested who have a PSA of less than 2.5 ng/mL, may only need to be retested every 2 y.” “Screening should be done yearly for men whose PSA level is 2.5 ng/mL or higher.” |

| American Urological Association | Well-informed men who wish to pursue early diagnosis | There should be no PSA screening in men younger than 40 y. There should be no routine screening in men aged between 40 and 54 y at average risk. There should be shared decision making for men aged 55 to 69 y who are considering PSA screening, and proceed based on a man’s values and preferences. There should be no routine PSA screening in men aged 70+ y or any man with less than a 10- to 15-y life expectancy. | There should be a routine screening interval of 2 y or more, individualized by a baseline PSA level. |

| European Association of Urology | Insufficient evidence to recommend widespread population-based PSA screening Early detection (opportunistic screening) offered to well-informed men | There should be a baseline PSA at 40 y. | Base the subsequent screening interval on the baseline PSA. A screening interval of 8 y might be enough in men with initial PSA levels <1 ng/mL. Further PSA testing is not necessary in men older than 75 y and a baseline PSA <3 ng/mL because of their very low risk of dying of prostate cancer. |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network | Informed discussion | There should be baseline DRE and PSA at 40 y. There should be annual screening at 50 y. | The algorithm is based on initial testing. Repeat screening at 45 y of age if the PSA is <1.0 ng/mL. |

| American College of Preventive Medicine | Insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening | Discussion about screening should occur annually, during the routine periodic examination, or in response to a request by patients. | — |

| Melbourne Consensus Statement | Routine population-based screening not recommended | Healthy, well-informed men (aged 55–69 y) should be fully counseled about the positive and negative aspects of PSA testing to reduce their risk of metastases and death; a baseline PSA in the 40s has value for risk stratification. All should be part of the shared decision-making process. | — |

| Japanese Urological Association | Recommends PSA screening | Candidates for PSA screening are men aged 50 y or older in general and 40 y or older in men with a family history. | The optimal screening interval cannot be stated at present but might be closely related to baseline PSA levels; it should be once every 3 y for men with baseline PSA levels lower than 1.0 ng/mL and annually for men with baseline PSA levels >1.0 ng/mL. |

Recently, the debate was refueled with the release of updated guidelines on PSA testing by the American Urological Association (AUA). Purely considering the available evidence and addressing both early detection and screening asymptomatic men, the panel recommends against PSA testing in men younger than 40 years. The panel does not recommend routine screening in men aged between 40 and 54 years at average risk; for men aged 55 to 69 years, the panel recommends shared decision making. In addition, the panel advises a 2-year or more screening interval to reduce the harms of screening and intervals for rescreening to be individualized by a baseline PSA level in men with more than average risk on developing PC. With respect to the upper age cutoff for screening, no routine PSA screening in men aged 70 years and older or any man with less than a 10- to 15-year life expectancy is advised. However, men aged 70 years and older who are in excellent health may benefit from prostate cancer screening. As expected, similar to the ongoing debate on the 2 randomized trials, these guidelines resulted in a fierce debate, which is still ongoing. Although the actual recommendations of the AUA’s guidelines are generally accepted, it is more the way they are presented and, hence, interpreted. The 5 statements primarily address asymptomatic men and as a result recommendations applying to men at higher risk appear to have been lost in the emphasis. Altogether these contradictory scientific publications, editorials, guidelines, and public discussions are extremely confusing for both clinicians and laypeople. The worldwide urological association (Societe International d’Urologie) has, to be of aid in this dilemma, released 3 decision aids for urologists, general practitioners (GPs), and laypeople. It is obvious that an important task awaits the scientists working on prostate cancer screening and early detection and that this controversy, leading to uncertainty, needs to be resolved as soon as possible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree