Emergency Diagnosis and Management

About 10% of all injuries seen in the emergency room involve the genitourinary system to some extent. Many of them are subtle and difficult to define and require great diagnostic expertise. Early diagnosis is essential to prevent serious complications.

Initial assessment should include control of hemorrhage and shock along with resuscitation as required. Resuscitation may require intravenous lines and a urethral catheter in seriously injured patients. In men, before the catheter is inserted, the urethral meatus should be examined carefully for the presence of blood.

The history should include a detailed description of the accident. In cases involving gunshot wounds, the type and caliber of the weapon should be determined, since high-velocity projectiles cause much more extensive damage.

The abdomen and genitalia should be examined for evidence of contusions or subcutaneous hematomas, which might indicate deeper injuries to the retroperitoneum and pelvic structures. Fractures of the lower ribs are often associated with renal injuries, and pelvic fractures often accompany bladder and urethral injuries. Diffuse abdominal tenderness is consistent with perforated bowel, free intraperitoneal blood or urine, or retroperitoneal hematoma. Patients who do not have life-threatening injuries and whose blood pressure is stable can undergo more deliberate radiographic studies. This provides more definitive staging of the injury.

When genitourinary tract injury is suspected on the basis of the history and physical examination, additional studies are required to establish its extent.

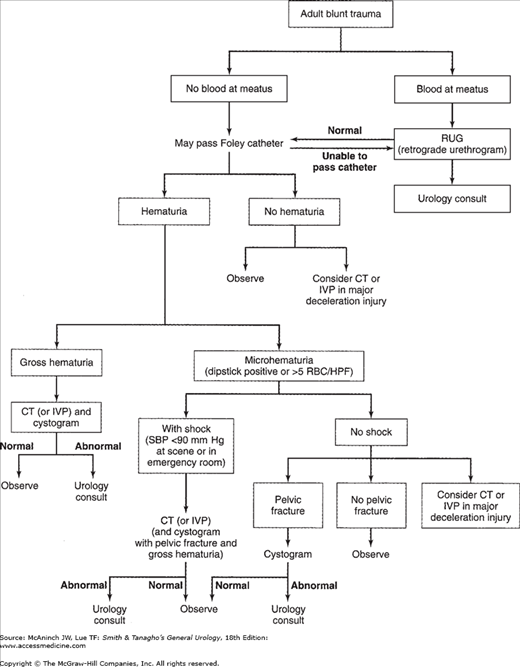

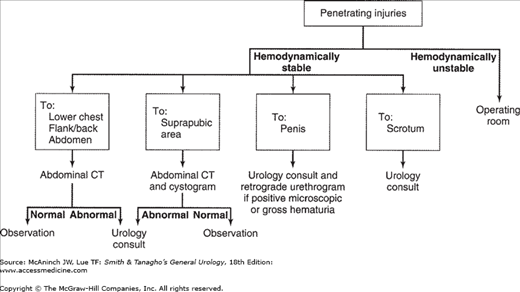

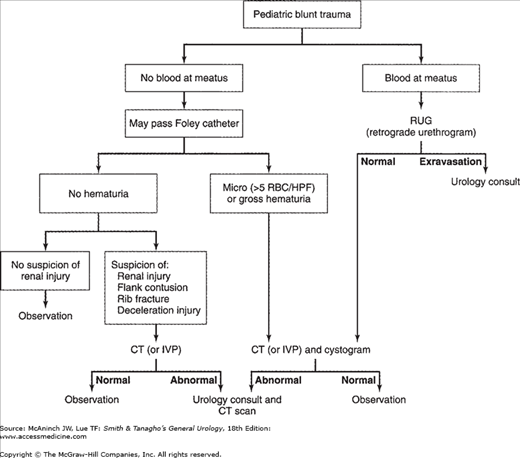

Assessment of the injury should be done in an orderly fashion so that accurate and complete information is obtained. This process of defining the extent of injury is termed staging. The algorithms (Figures 18–1, 18–2, and 18–3) outline the staging process for urogenital trauma.

Blood at the urethral meatus in men indicates urethral injury; catheterization should not be attempted if blood is present, but retrograde urethrography should be done immediately. If no blood is present at the meatus, a urethral catheter can be carefully passed to the bladder to recover urine; microscopic or gross hematuria indicates urinary system injury. If catheterization is traumatic despite the greatest care, the significance of hematuria cannot be determined, and other studies must be done to investigate the possibility of urinary system injury.

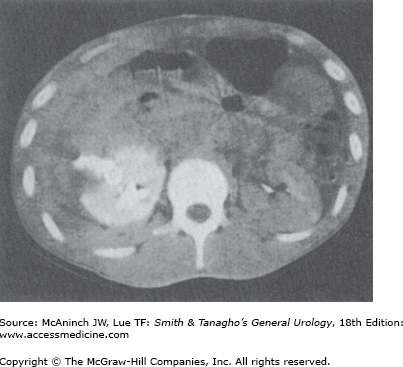

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) with contrast media is the best imaging study to detect and stage renal and retroperitoneal injuries. It can define the size and extent of the retroperitoneal hematoma, renal lacerations, urinary extravasation, and renal arterial and venous injuries; additionally, it can detect intra-abdominal injuries (liver, spleen, pancreas, bowel). Spiral CT scanning, now common, is very rapid, but it may not detect urinary extravasation or ureteral and renal pelvic injuries. We recommend repeat scanning 10 minutes after the initial study to aid the diagnosis of these conditions.

Filling of the bladder with contrast material is essential to establish whether bladder perforations exist. At least 300 mL of contrast medium should be instilled for full vesical distention. A film should be obtained with the bladder filled and a second one after the bladder has emptied itself by gravity drainage. These two films establish the degree of bladder injury as well as the size of the surrounding pelvic hematomas.

Cystography with CT scan is excellent for establishing bladder injury. At the time of scanning, this likewise must be done with retrograde filling of the bladder with 300 mL of contrast media to ensure adequate distention to detect injury.

A small (12F) catheter can be inserted into the urethral meatus and 3 mL of water placed in the balloon to hold the catheter in position. After retrograde injection of 20 mL of water-soluble contrast material, the urethra will be clearly outlined on film, and extravasation in the deep bulbar area in case of straddle injury—or free extravasation into the retropubic space in case of prostatomembranous disruption—will be visualized.

Arteriography may help define renal parenchymal and renal vascular injuries. It is also useful in the detection of persistent bleeding from pelvic fractures for purposes of embolization with Gelfoam or autologous clot.

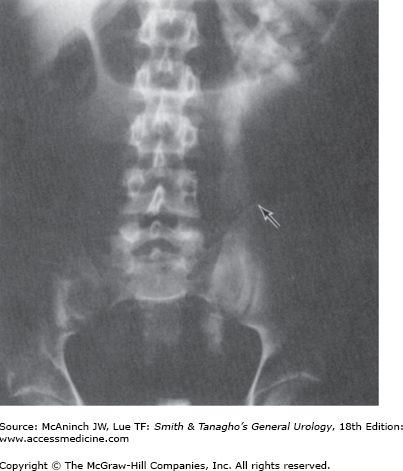

Intravenous urography can be used to detect renal and ureteral injury. This is best done with high-dose bolus injection of contrast media (2.0 mL/kg) followed by appropriate films.

Cystoscopy and retrograde urography may be useful to detect ureteral injury, but are seldom necessary, since information can be obtained by less invasive techniques.

Abdominal sonography has not been shown to add substantial information during initial evaluation of severe abdominal trauma.

Injuries to the Kidney

Renal injuries are the most common injuries of the urinary system. The kidney is well protected by heavy lumbar muscles, vertebral bodies, ribs, and the viscera anteriorly. Fractured ribs and transverse vertebral processes may penetrate the renal parenchyma or vasculature. Most injuries occur from automobile accidents or sporting mishaps, chiefly in men and boys. Kidneys with existing pathologic conditions such as hydronephrosis or malignant tumors are more readily ruptured from mild trauma.

Blunt trauma directly to the abdomen, flank, or back is the most common mechanism, accounting for 80–85% of all renal injuries. Trauma may result from motor vehicle accidents, fights, falls, and contact sports. Vehicle collisions at high speed may result in major renal trauma from rapid deceleration and cause major vascular injury. Gunshot and knife wounds cause most penetrating injuries to the kidney; any such wound in the flank area should be regarded as a cause of renal injury until proved otherwise. Associated abdominal visceral injuries are present in 80% of renal penetrating wounds.

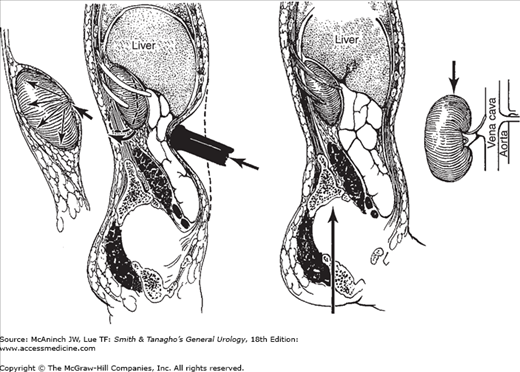

Figure 18–4.

Mechanisms of renal injury. Left: Direct blow to abdomen. Smaller drawing shows force of blow radiating from the renal hilum. Right: Falling on buttocks from a height (contrecoup of kidney). Smaller drawing shows direction of force exerted on the kidney from above. Tear of renal pedicle.

Lacerations from blunt trauma usually occur in the transverse plane of the kidney. The mechanism of injury is thought to be force transmitted from the center of the impact to the renal parenchyma. In injuries from rapid deceleration, the kidney moves upward or downward, causing sudden stretch on the renal pedicle and sometimes complete or partial avulsion. Acute thrombosis of the renal artery may be caused by an intimal tear from rapid deceleration injuries owing to the sudden stretch.

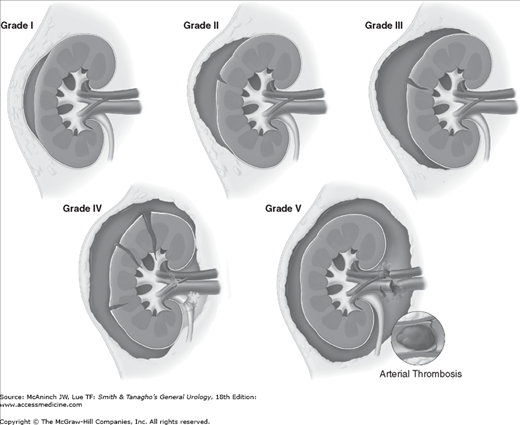

Pathologic classification of renal injuries is as follows:

- Grade 1 (the most common)—Renal contusion or bruising of the renal parenchyma. Microscopic hematuria is common, but gross hematuria rarely occurs.

- Grade 2—Renal parenchymal laceration into the renal cortex. Perirenal hematoma is usually small.

- Grade 3—Renal parenchymal laceration extending through the cortex and into the renal medulla. Bleeding can be significant in the presence of large retroperitoneal hematoma.

- Grade 4—Renal parenchymal laceration (single or multiple) extending into the renal collecting system; also main renal artery thrombosis from blunt trauma, segmental renal vein, or both; or artery injury with contained bleeding.

- Grade 5—Multiple Grade 4 parenchymal lacerations, renal pedicle avulsion, or both; main renal vein or artery injury from penetrating trauma; main renal artery or vein thrombosis.

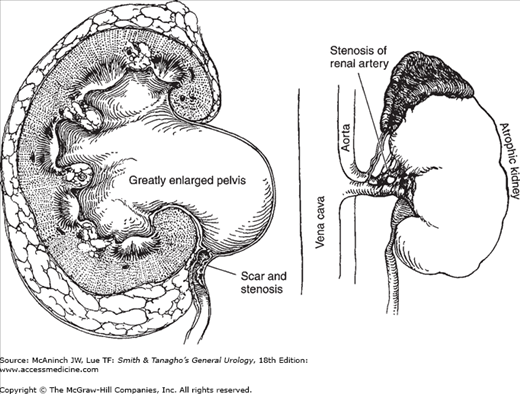

Deep lacerations that are not repaired may result in persistent urinary extravasation and late complications of a large perinephric renal mass and, eventually, hydronephrosis and abscess formation.

Large hematomas in the retroperitoneum and associated urinary extravasation may result in perinephric fibrosis engulfing the ureteropelvic junction, causing hydronephrosis. Follow-up excretory urography is indicated in all cases of major renal trauma.

Arteriovenous fistulas may occur after penetrating injuries but are not common.

The blood flow in tissue rendered nonviable by injury is compromised; this results in renal vascular hypertension in <1% of cases. Fibrosis from surrounding trauma has also been reported to constrict the renal artery and cause renal hypertension.

Microscopic or gross hematuria following trauma to the abdomen indicates injury to the urinary tract. It bears repeating that stab or gunshot wounds to the flank area should alert the physician to possible renal injury whether or not hematuria is present. Some cases of renal vascular injury are not associated with hematuria. These cases are almost always due to rapid deceleration accidents and are an indication for imaging studies.

The degree of renal injury does not correspond to the degree of hematuria, since gross hematuria may occur in minor renal trauma and only mild hematuria in major trauma. However, not all adult patients sustaining blunt trauma require full imaging evaluation of the kidney (Figure 18–1). Miller and McAninch (1995) made the following recommendations based on findings in >1800 blunt renal trauma injuries: Patients with gross hematuria or microscopic hematuria with shock (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg) should undergo radiographic assessment; patients with microscopic hematuria without shock need not. However, should physical examination or associated injuries prompt reasonable suspicion of a renal injury, renal imaging should be undertaken. This is especially true of patients with rapid deceleration trauma, who may have renal injury without the presence of hematuria.

There is usually visible evidence of abdominal trauma. Pain may be localized to one flank area or over the abdomen. Associated injuries such as ruptured abdominal viscera or multiple pelvic fractures also cause acute abdominal pain and may obscure the presence of renal injury. Catheterization usually reveals hematuria. Retroperitoneal bleeding may cause abdominal distention, ileus, and nausea and vomiting.

Initially, shock or signs of a large loss of blood from heavy retroperitoneal bleeding may be noted. Ecchymosis in the flank or upper quadrants of the abdomen is often noted. Lower rib fractures are frequently found. Diffuse abdominal tenderness may be found on palpation; an “acute abdomen” usually indicates free blood in the peritoneal cavity. A palpable mass may represent a large retroperitoneal hematoma or perhaps urinary extravasation. If the retroperitoneum has been torn, free blood may be noted in the peritoneal cavity but no palpable mass will be evident. The abdomen may be distended and bowel sounds absent.

Microscopic or gross hematuria is usually present. The hematocrit may be normal initially, but a drop may be found when serial studies are done. This finding represents persistent retroperitoneal bleeding and development of a large retroperitoneal hematoma. Persistent bleeding may necessitate operation.

Staging of renal injuries allows a systematic approach to these problems (Figures 18–1, 18–2, and 18–3). Adequate studies help define the extent of injury and dictate appropriate management. For example, blunt trauma to the abdomen associated with gross hematuria and a normal urogram requires no additional renal studies; however, nonvisualization of the kidney requires immediate arteriography or CT scan to determine whether renal vascular injury exists. Ultrasonography and retrograde urography are of little use initially in the evaluation of renal injuries.

Staging begins with an abdominal CT scan, the most direct and effective means of staging renal injuries. This noninvasive technique clearly defines parenchymal lacerations and urinary extravasation; shows the extent of the retroperitoneal hematoma; identifies nonviable tissue; and outlines injuries to surrounding organs such as the pancreas, spleen, liver, and bowel (Figure 18–7). (If CT scan is not available, an intravenous pyelogram can be obtained [Figure 18–8].)

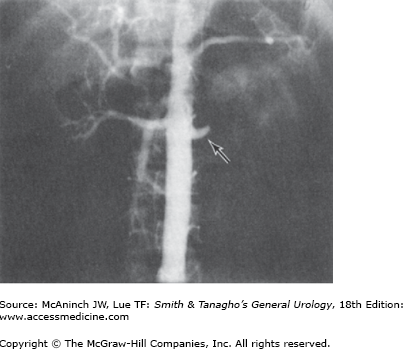

Arteriography defines major arterial and parenchymal injuries when previous studies have not fully done so. Arterial thrombosis and avulsion of the renal pedicle are best diagnosed by arteriography and are likely when the kidney is not visualized on imaging studies (Figure 18–9). The major causes of nonvisualization on an excretory urogram are total pedicle avulsion, arterial thrombosis, severe contusion causing vascular spasm, and absence of the kidney (either congenital or from operation).

Radionuclide renal scans have been used in staging renal trauma. However, in emergency management, this technique is less sensitive than arteriography or CT.

Trauma to the abdomen and flank areas is not always associated with renal injury. In such cases, there is no hematuria, and the results of imaging studies are normal.

Hemorrhage is perhaps the most important immediate complication of renal injury. Heavy retroperitoneal bleeding may result in rapid exsanguination. Patients must be observed closely, with careful monitoring of blood pressure and hematocrit. Complete staging must be done early (Figures 18–1, 18–2, and 18–3). The size and expansion of palpable masses must be carefully monitored. Bleeding ceases spontaneously in 80–85% of cases. Persistent retroperitoneal bleeding or heavy gross hematuria may require early operation.

Urinary extravasation from renal fracture may show as an expanding mass (urinoma) in the retroperitoneum. These collections are prone to abscess formation and sepsis. A resolving retroperitoneal hematoma may cause slight fever (38.3°C [101°F]), but higher temperatures suggest infection. A perinephric abscess may form, resulting in abdominal tenderness and flank pain.

Hypertension, hydronephrosis, arteriovenous fistula, calculus formation, and pyelonephritis are important late complications. Careful monitoring of blood pressure for several months is necessary to watch for hypertension. At 3–6 months, a follow-up excretory urogram or CT scan should be obtained to be certain that perinephric scarring has not caused hydronephrosis or vascular compromise; renal atrophy may occur from vascular compromise and is detected by follow-up urography. Heavy late bleeding may occur 1–4 weeks after injury.

The objectives of early management are prompt treatment of shock and hemorrhage, complete resuscitation, and evaluation of associated injuries.

Minor renal injuries from blunt trauma account for 85% of cases and do not usually require operation. Bleeding stops spontaneously with bed rest and hydration. Cases in which operation is indicated include those associated with persistent retroperitoneal bleeding, urinary extravasation, evidence of nonviable renal parenchyma, and renal pedicle injuries (<5% of all renal injuries). Aggressive preoperative staging allows complete definition of injury before operation.

Penetrating injuries should be surgically explored. A rare exception to this rule is when staging has been complete and only minor parenchymal injury, with no urinary extravasation, is noted. In 80% of cases of penetrating injury, associated organ injury requires operation; thus, renal exploration is only an extension of this procedure.

Retroperitoneal urinoma or perinephric abscess demands prompt surgical drainage. Malignant hypertension requires vascular repair or nephrectomy. Hydronephrosis may require surgical correction or nephrectomy.

Angioembolization done by interventional radiology provides excellent control of active bleeding from the kidney. This approach, in the trauma setting, is most often used when nonoperative management has been selected and renal parenchymal bleeding persists or develops after days or weeks of observation.

Injuries to the Ureter

Ureteral injury is rare but may occur, usually during the course of a difficult pelvic surgical procedure or as a result of stab or gunshot wounds. Rapid deceleration accidents may avulse the ureter from the renal pelvis. Endoscopic basket manipulation of ureteral calculi may result in injury.

Large pelvic masses (benign or malignant) may displace the ureter laterally and engulf it in reactive fibrosis. This may lead to ureteral injury during dissection, since the organ is anatomically malpositioned. Inflammatory pelvic disorders may involve the ureter in a similar way. Extensive carcinoma of the colon may invade areas outside the colon wall and directly involve the ureter; thus, resection of the ureter may be required along with resection of the tumor mass. Devascularization may occur with extensive pelvic lymph node dissections or after radiation therapy to the pelvis for pelvic cancer. In these situations, ureteral fibrosis and subsequent stricture formation may develop along with ureteral fistulas. Endoscopic manipulation of a ureteral calculus with a stone basket or ureteroscope may result in ureteral perforation or avulsion.

The ureter may be inadvertently ligated and cut during difficult pelvic surgery. In such cases, sepsis and severe renal damage usually occur postoperatively. If a partially divided ureter is unrecognized at operation, urinary extravasation and subsequent buildup of a large urinoma will ensue, which usually leads to ureterovaginal or ureterocutaneous fistula formation. Intraperitoneal extravasation of urine can also occur, causing ileus and peritonitis. After partial transection of the ureter, some degree of stenosis and reactive fibrosis develops, with concomitant mild-to-moderate hydronephrosis.