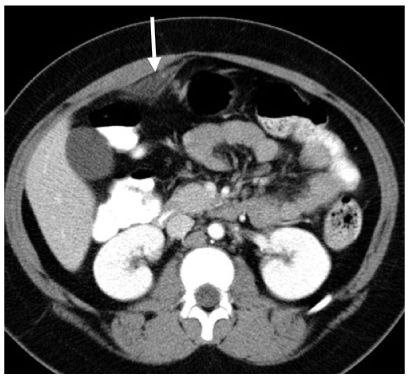

Fig. 1

Appendicitis. Coronal reformatted computed tomography (CT) scan shows a dilated, inflamed, fluid-filled appendix (arrow) along the lateral aspect of the right psoas muscle

Contrast-enhanced CT is the preferred imaging technique in patients with suspected appendicitis. In patients who cannot receive iodinated intravenously administered contrast material, the diagnosis of acute appendicitis requires the detection of a thickened appendix (diameter >6 mm), with associated inflammatory changes in the periappendiceal fat or abnormal thickening of the right lateroconal fascia, with or without a calcified appendicolith. The detection of an appendicolith confirms a specific diagnosis of appendicitis in the appropriate clinical setting. An appendicolith can be visualized on CT in approximately 28% of adult patients (compared with 10% for plain abdominal radiographs), reflecting the higher sensitivity of CT in detecting small, intra-abdominal calcifications [15–20]. The addition of coronal and sagittal reformatted images increases confidence in establishing the correct diagnosis by virtue of more reliable demonstration of the entire appendix, surrounding fat and lymph nodes, and periappendiceal infection and inflammation.

The combination of right lower-quadrant inflammation, a phlegmon, and an abscess adjacent to the cecum is suggestive but not diagnostic of appendicitis. Indeed, if an abnormal appendix or an appendicolith is not shown, the differential diagnosis also must include Crohn’s disease, cecal diverticulitis, ileal diverticulitis, perforated cecal carcinoma, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Abscesses may be found in locations distant from the cecum because of the length and position of the appendix and the patterns of fluid migration in the peritoneal cavity.

The majority (60–70%) of patients referred for crosssectional imaging with suspected appendicitis do not have this disease. Although most patients have benign, self-limited gastrointestinal disorders, such as viral gastroenteritis, CT and US often suggest a specific alternate diagnosis [15–20]. Adnexal cysts, masses, salpingitis, and tubo-ovarian abscesses are readily shown on US. Ureteral calculi and pyelonephritis can be detected on CT and US. Enlarged lymph nodes in the right lower quadrant suggest mesenteric adenitis or infectious ileitis; mural thickening of the terminal ileum can be seen in Crohn’s disease or infectious ileitis.

Although CT has a higher accuracy than US, sonography is often initially employed in pediatric and pregnant patients. MRI combines the lack of ionizing radiation exposure with high-contrast resolution, cross-sectional imaging. Initial reports on MRI in diagnosing acute appendicitis are encouraging in pregnant women [21–24].

Diverticulitis

It is estimated that 10–25% of individuals with diverticulosis will suffer from diverticulitis. In the United States, this complication accounts for approximately 200,000 hospitalizations and a health care expenditure of $4 billion. Among patients who are hospitalized, 10–20% requires emergency operation [25–28].

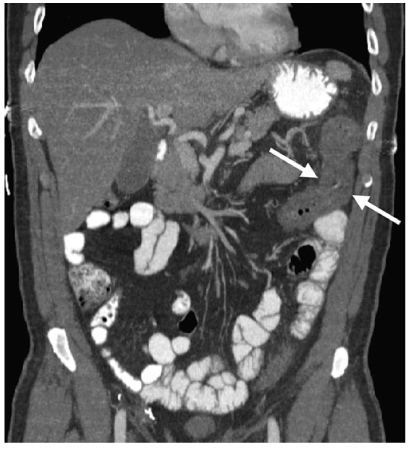

Inflammatory change in the pericolic fat is the hallmark of diverticulitis on CT (Fig. 2) and is seen in 98% of cases. The extent of the inflammatory reaction is related to the size of the perforation, bacterial contamination, and host response. Mild cases may manifest as areas of slight increase in fat density adjacent to the involved colon or as fine linear strands with small, fluid collections or bubbles of extraluminal air. In sigmoid diverticulitis, the fluid is typically decompressed into the inferior portion of the combined interfascial plane. Due to hypervascularity of the inflamed area, contrast-enhanced CT scans often reveal engorged mesenteric vessels in the involved pericolic fat. Pericolic heterogeneous soft-tissue densities representing phlegmons and partially loculated fluid collections indicating abscess are seen in more severe cases. The abscess cavities usually contain air bubbles or air-fluid levels. They develop within the sigmoid mesocolon or are sealed off by the sigmoid colon and adjacent small-bowel loops. Less commonly, abscesses may form in the groin, flank, thigh, psoas muscle, subphrenic space or liver [29–33].

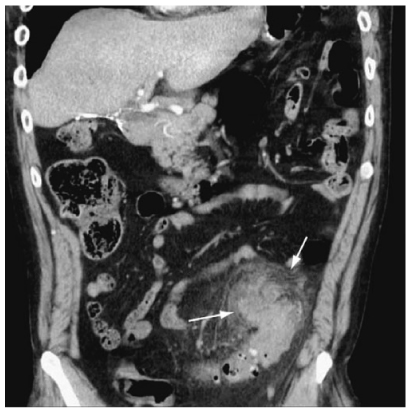

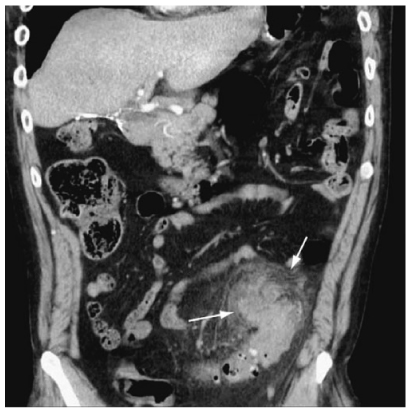

Fig. 2

Diverticulitis. Coronal reformatted computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrates a large phlegmon in the sigmoid mesocolon (arrows)

Diverticula are seen at the site of perforation or adjacent to it in about 80% of cases on CT. They appear as small outpouchings of air, contrast, or fecal material projecting through the colonic wall. Symmetric mural thickening of the involved colon of approximately 4–10 mm is seen in about 70% of cases; however, if there is marked muscular hypertrophy, the wall of the colon can measure up to 2–3 cm in thickness [34].

CT can also demonstrate intramural abscesses and fistula and is helpful in patients with suspected colovesical fistulas. In the latter case, a pericolic inflammatory mass is seen involving the bladder wall; intraluminal gas confirms the diagnosis [35].

CT reports sensitivity of up to 98% when diagnosing diverticulitis. Additionally, it demonstrates disease extension, such as abscess and peritonitis remote from the colon, and can guide percutaneous abscess drainage. CT can diagnose other pathological conditions that can clinically simulate diverticulitis [29–35].

Epiploic Appendagitis

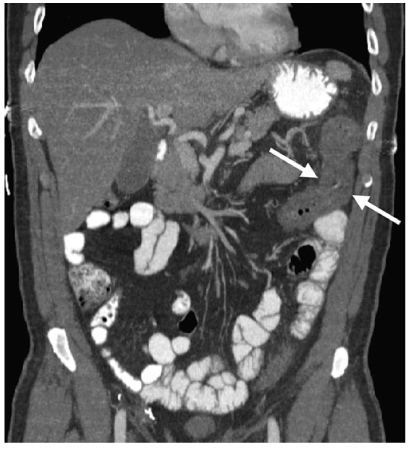

Primary epiploic appendagitis is a relatively uncommon condition that results from acute inflammation and/or torsion and infarction of the appendices epiploicae. Clinically, epiploic appendagitis can simulate diverticulitis if it occurs in the sigmoid and appendicitis if it occurs in the proximal colon. CT reveals a characteristic appearance of a small, round, or oval fat-containing mass (Fig. 3) with associated inflammatory reaction of the pericolic fat. A thrombosed central vessel can sometimes be identified centrally [38–41]. Epiploic appendagitis is a self-limited process, with clinical resolution in a few days. Follow-up CT examination may show total resolution, with shrinkage and eventual calcification of the inflamed and infarcted epiploic appendix [42, 43].

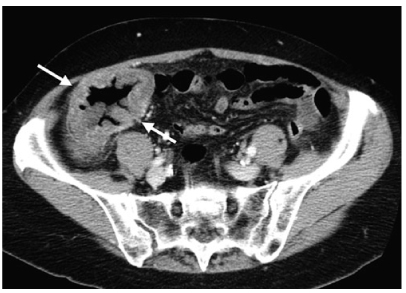

Fig. 3

Epiploic appendagitis. Axial computed tomography (CT) scan depicts an infarcted epiploic appendage with a central thrombosed vein (arrow)

Omental Torsion and Infarction

Omental torsion and infarction are uncommon disorders. Portions of the greater omentum undergo torsion, spontaneous venous thrombosis, or both, which leads to severe abdominal pain associated with exquisite point tenderness. This usually occurs in the right lower quadrant, in which case it clinically mimics acute appendicitis, or in the right upper quadrant, in which case acute cholecystitis is simulated [44, 45].

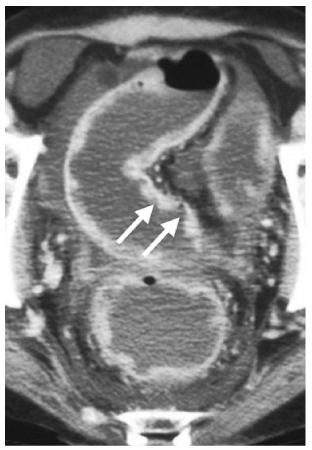

CT demonstrates a region of increased attenuation (Fig. 4) within the greater omentum in the involved segment. This abnormal fat must be differentiated from an omental primary or secondary malignancy (e.g., carcinomatosis), omental infection (e.g., tuberculosis), and epiploic appendagitis. The size of the omental abnormality typically is larger in omental infarction and torsion than in epiploic appendagitis [46–49].

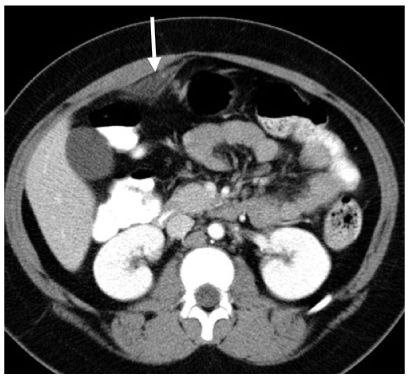

Fig. 4

Omental infarction. Axial computed tomography (CT) shows a focal region of abnormal omental fat (arrow). This area was exquisitely tender to palpation

Ischemic Colitis

Vascular insufficiency of the colon should be on the differential diagnosis of any elderly patient with acute or chronic abdominal pain and for all patients with a history of coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, arteritis, hypotension, dehydration, or cardiac decompensation. The major cause of colonic ischemia is nonocclusive hypoperfusion disorders, but it can also be seen in the setting of arterial or venous occlusion or thrombosis [50–52].

CT manifestations of ischemic colitis depend upon its cause, chronicity, and severity. Mural thickening of the gut is the most common finding and is often associated with submucosal edema (Fig. 5). This appearance is non specific and can be seen in infectious and inflammatory colonic disease. The presence of pneumatosis or thrombus within the superior or inferior mesenteric arteries permits a specific diagnosis to be made. The distribution frequency of ischemic colitis is: left colon (32.6%), distal colon (24.6%), right colon (25.2%), transverse colon (10.2%), and pan colitis (7.3%) [53–56].

Fig. 5

Ischemic colitis. Coronal reformatted computed tomography (CT) reveals mural thickening of the splenic flexure of the colon (arrows), the most common location for colonic ischemia

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is characterized pathologically by extensive ulceration and diffuse inflammation of the mucosa. The disease characteristically begins in the rectum and extends proximally in a contiguous fashion to involve part, or all, of the colon. Pathological changes found in the very early stages of ulcerative colitis are beneath the spatial resolution of CT. With progressive disease, submucosal edema producing a target sign may be seen. Severe mucosal ulceration can denude certain portions of the colonic wall, leading to inflammatory pseudopolyps (Fig. 6). When sufficiently large, these pseudopolyps can be visualized on CT. Mural thickening and lumen narrowing are the CT hallmarks of subacute and chronic ulcerative colitides. Mural thinning, unsuspected perforations, and pneumatosis can be detected on CT in patients with toxic megacolon. In this regard, CT can be quite helpful in determining the urgency of surgery in patients with stable abdominal radiographs yet who present a deteriorating clinical course [57–62].

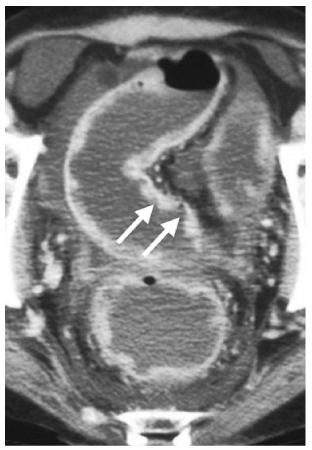

Fig. 6

Ulcerative colitis. Axial computed tomography (CT) demonstrates deeps ulcerations (arrows), with intervening surviving mucosa producing inflammatory pseudopolyps in this patient with severe disease. Notice the ascites

In chronic ulcerative colitis, the muscularis mucosae become markedly hypertrophied, often by a factor of 40. Forceful contraction also causes shortening of the colon. The submucosa becomes thickened due to the deposition of fat or, in acute and subacute cases, edema. Submucosal thickening further contributes to lumen narrowing. Additionally, the lamina propria is thickened due to round-cell infiltration in both acute and chronic ulcerative colitis.

On CT, these mural changes produce a target or halo appearance when axially imaged: the lumen is surrounded by a ring of soft tissue density (mucosa, lamina propria, hypertrophied muscularis mucosae). This is surrounded by a low-density ring (fatty infiltration of the submucosa), which in turn is surrounded by a ring of soft tissue density (muscularis propria). This mural stratification is not specific and can also be seen in Crohn–s disease, infectious enterocolitis, pseudomembranous colitis, ischemic and radiation enterocolitides, mesenteric venous thrombosis, bowel edema, and graft-versus-host disease [57–62].

There are certain CT findings that can help differentiate Crohn’s colitis and ulcerative colitis. Mural stratification, i.e., the ability to visualize individual layers of bowel wall, is seen in chronic Crohn’s colitis. Also, mean colon-wall thickness in chronic ulcerative colitis is 7.8 mm, significantly thinner than that observed in Crohn’s colitis (11 mm). Finally, the outer contour of the thickened colonic wall is smooth and regular in 95% of ulcerative colitis cases, whereas serosal and outer mural irregularities are present in 80% of patients with Crohn’s colitis [57–62].

Rectal narrowing and widening of the presacral space are hallmarks of chronic ulcerative colitis. CT depicts the anatomic alterations that underlie these rather dramatic morphologic changes. The rectal lumen is narrowed due to the previously described mural thickening that attends chronic ulcerative colitis. As a result, the rectum has a target appearance on axial scans, which should not be mistaken for the external anal sphincter, mucosal prolapse, or the levator ani muscles. The increase in the presacral space is caused by proliferation of the perirectal fat. On CT, this fat is characterized by an increased number of nodular and streaky soft tissue densities and an abnormal attenuation value 10–20 Hounsfield units (HU) higher than the normal extraperitoneal or mesenteric fat. These fatty changes relate to a number of factors, including ex vacuo replacement by fat of the void produced by rectal lumen narrowing and lipodystrophy resulting from an influx of inflammatory cells and edema. Edematous adipose tissue and enlarged lymph nodes are often observed in the perirectal region at the time of abdominoperineal resections in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis [63–66].

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease most commonly affects the terminal ileum and proximal colon. The acute, active phase of Crohn’s disease is characterized by focal inflammation, aphthoid ulceration with adjacent cobblestoning, an often transmural inflammatory reaction, with lymphoid aggregates and granuloma formation, fissures, fistula, and sinus tracts. The chronic and resolving phase of this disorder is associated with fibrosis and stricture formation [57–60].

US, CT, and MRI can be used to determine the presence and extent of Crohn’s disease [61–74]. When Crohn’s disease is limited to the mucosa, the CT scan is often normal. Although inflammatory and postinflammatory pseudopolyps may be identified on CT, the assessment of the mucosa is best reserved for barium studies and colonoscopy, which are more direct and sensitive. Crohn’s disease is manifested on CT by bowel-wall thickening of 1–2 cm (Fig. 7). This thickening, which occurs in up to 83% of patients, is most frequently observed in the terminal ileum, but other portions of the small bowel, colon, duodenum, stomach, and esophagus may be similarly affected [60–74].

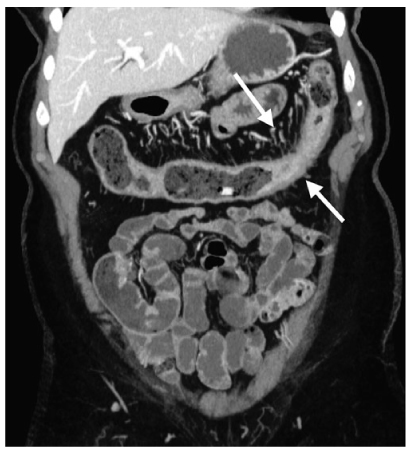

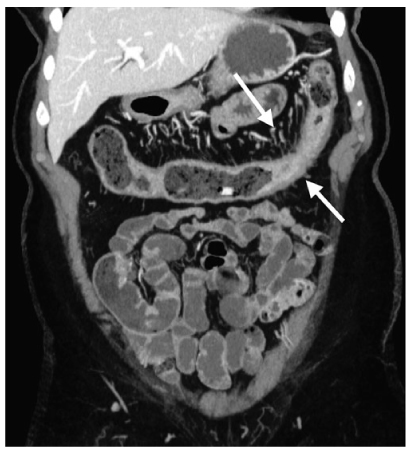

Fig. 7

Crohn’s disease. Coronal reformatted computed tomography (CT) depicts mural thickening of the transverse colon (arrows) and engorgement of the vasa rectae

During the acute, noncicatrizing phase of Crohn’s disease, the small bowel and colon maintain mural stratification and often have a target or double-halo appearance. As in ulcerative colitis, there is a soft-tissue density ring (corresponding to mucosa), which is surrounded by a low-density ring with an attenuation near that of water or fat (corresponding to submucosal edema or fat infiltration, respectively), which in turn is surrounded by a higher density ring (muscularis propria). Inflamed mucosa and serosa may show significant contrast enhancement following bolus contrast administration intravenously, and the intensity of enhancement correlates with the clinical activity of the disease [60–74].

CT demonstration of mural stratification, i.e., the ability to visualize distinct mucosal, submucosal, and muscularis propria layers, indicates that transmural fibrosis has not occurred and that medical therapy may be successful in ameliorating lumen compromise. Additionally, prior to fibrosis onset, edema and inflammation of the bowel wall, which cause mural thickening and leman obstruction, are reversible to some extent. A modest decrease in wall thickness often produces a dramatic increase in lumen cross-sectional area and resolution of obstructive symptoms. Loss of mural stratification is indicative of transmural fibrosis [60–74].

In patients with long-standing Crohn’s disease and transmural fibrosis, mural stratification is lost, so that the affected bowel wall typically has homogeneous attenuation on CT. Homogeneous attenuation of the thickened bowel wall suggests irreversible fibrosis, so that antiinflammatory agents may not provide significant reduction in bowel-wall thickness. If these segments become sufficiently narrow, surgery or stricturoplasty will be necessary to relieve the obstruction.

Palpation of an abdominal mass or separation of bowel loops on a barium study in a patient with Crohn’s disease evokes a large differential diagnosis: abscess, phlegmon, “creeping fat” or fibrofatty proliferation of the mesentery, bowel-wall thickening, and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes. Each of these disorders has significantly different prognostic and therapeutic implications. This diagnostic dilemma is further complicated by the fact that many patients are receiving immunosuppressive therapy, which can mask signs and symptoms. CT can readily differentiate the extraluminal manifestations of Crohn’s disease.

Fibrofatty proliferation, also known as creeping fat of the mesentery, is the most common cause of separation of bowel loops seen on barium studies in patients with Crohn’s disease. On CT, the sharp interface between bowel and mesentery is lost, and the attenuation value of the fat is elevated by 20–60 HU due to the influx of inflammatory cells and fluid. Mesenteric adenopathy with lymph nodes ranging in size between 3 and 8 mm may also be present. If these lymph nodes are >1 cm, the presence of lymphoma or carcinoma, both of which occur with greater frequency in Crohn’s disease, must be excluded.

Contrast-enhanced CT scans often show hypervascularity of the involved mesentery, manifesting as vascular dilatation, tortuosity, prominence, and wide spacing of the vasa recta. These distinctive vascular changes have been called the comb sign. Identification of this hypervascularity should suggest active disease and may be useful in differentiating Crohn’s from lymphoma or metastases, which tend to be hypovascular lesions.

CT enterography has become an important technique for evaluating the small bowel in patients with Crohn’s disease because of its accuracy and noninvasive nature. As colonic involvement is common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, the capability of this technique for evaluating colorectal involvement is being studied, and preliminary results are encouraging.

As patients with Crohn’s disease are often young and typically will require multiple examinations, the cumulative dose of ionizing radiation from multiple CT examinations has the potential to be substantial. Accordingly, the use of an accurate technique without ionizing radiation, such as MRI, is most attractive [75–80].

Pseudomembranous Colitis

Pseudomembranous colitis is being encountered with increasing frequency as a nosocomial infection complicating antibiotic therapy. This potentially life-threatening disorder is caused by overgrowth of Clostridium difficile and the subsequent release of a cytotoxic enterotoxin that causes ulceration of the colonic mucosa and formation of 2- to 3-mm pseudomembranes consisting of fibrin, mucus, sloughed epithelial cells, and leukocytes. Mild cases may demonstrate only mucosal irregularity and nodularity, with small plaque formation that cannot be detected radiologically. In advanced cases, there is thickening of haustral folds, a shaggy wall contour, and mucosal plaques [81–84].

CT shows colitis with mural thickening that may be irregular or polypoid and have a shaggy endoluminal contour. Mural thickening, which is usually 1.6–1.8 cm, is a result of submucosal edema. Mucosal and serosal enhancement is seen following intravenous administration of contrast material. The haustra are also thickened and edematous, producing the accordion pattern, which is highly suggestive of pseudomembranous colitis (Fig. 8). This pattern consists of contrast trapped between thickened haustral folds that are aligned in a parallel fashion. This appearance can sometimes simulate deep ulcerations or fissures. Pericolic stranding, ascites, pleural effusions, and subcutaneous edema are other ancillary CT findings. Complications of untreated pseudomembranous colitis include toxic megacolon, and intestinal perforation with subsequent peritonitis. CT is also useful in monitoring the response to medical therapy with vancomycin and metronidazole orally [81–84].

Fig. 8

Pseudomembranous colitis. Coronal reformatted computed tomography (CT) shows mural thickening of the sigmoid colon, with marked submucosal edema (arrow) producing the accordion sign. Note the ascites

Typhlitis

Typhlitis (neutropenic colitis) is a potentially fatal infection of the cecum and ascending colon caused by enteric pathogens in patients with severe immunosuppression. It is most frequently seen in patients with acute leukemia receiving chemotherapy but also occurs in the setting of AIDS, aplastic anemia, multiple myeloma, and bone marrow transplantation. Bacteria, viruses, and fungi penetrate the damaged cecal mucosa and proliferate due to the profound neutropenia. There is edema and inflammation of the cecum, ascending colon, and occasionally the ileum. Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are presenting symptoms. Prompt diagnosis and supportive therapy with intensive antibiotic and fluid administration are required to prevent transmural necrosis and perforation. Surgical resection is indicated in patients with transmural necrosis, intramural perforation, abscess, or uncontrolled sepsis and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Because of the inherent risks of bowel perforation in performing barium enemas and colonoscopies in these critically ill patients, CT is the study of choice. CT demonstrates circumferential mural thickening (1–3 cm) of the cecum (Fig. 9), low-density areas within the colonic wall secondary to edema, pericolonic inflammation and fluid, and, in severe cases, pneumatosis. Clinically, CT is used to monitor a decrease in mural thickness with therapy and to detect subtle pneumoperitoneum in cases of silent perforation or necrosis [81–84].