Chapter 37 Induction of Ovulation

INTRODUCTION

This chapter reviews the underlying scientific basis and clinical guidelines regarding the use of different oral medications for induction of ovulation. It focuses on a discussion of oral agents, including clomiphene citrate, insulin sensitizers, and aromatase inhibitors. Other drugs for ovarian stimulation used for assisted reproductive technology (ART), including preantral medications (injectable gonadotropins and gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] analogues), and specific agents applied for particular medical disorders, such as prolactin-lowering agents in cases of hyperprolactinemic anovulation, are discussed in Chapters 22 and 38.

PHYSIOLOGIC BASIS OF FOLLICULAR DEVELOPMENT AND OVULATION

An understanding of normal physiology is an important basis for understanding ovulation induction. Ovulation is comprehensively discussed in Chapter 3. A brief description relevant to induction of ovulation is presented here.

Folliculogenesis

Ovarian folliculogenesis is regulated by both endocrine and intraovarian mechanisms that coordinate the processes of cell proliferation and differentiation. The main follicular component of the ovarian cortex is the primordial follicle, consisting of an oocyte arrested at the diplotene stage of the first meiotic division, surrounded by a few flattened cells that will develop into granulosa cells.1 In response to an unknown signal, primordial follicles are gradually and continuously recruited to grow.

Initial Follicular Growth

Initial follicular growth appears to be independent of pituitary gonadotropins. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) does not appear to be essential for early follicle growth because in the absence of FSH follicles can still develop to the early antral stage. However, the involvement of FSH in the development of small follicles is supported by the presence of FSH receptors in granulosa cells.1 Also, FSH activates granulosa cell proliferation and differentiation and reduces the number of atretic follicles grown in vitro.2 Such mitogenic action is facilitated by locally produced growth factors; the production or action of these factors may be modified by FSH.3

Extrapolating from hypogonadal mice in which oocytes grow to normal size and can acquire developmental competence, gonadotropins may not be necessary for oocyte development per se. However, gonadotropins are believed to play a general role in supporting overall oocyte maturation by supporting follicular development and preventing degeneration.4

Early Follicular Development

During the early stage of follicular development, the oocyte grows and the granulosa cells proliferate to form a preantral follicle. At the preantral stage, theca cells begin to differentiate from the surrounding stroma, and once the follicle reaches a species-specific size, it forms a fluid-filled space called an antrum within the granulosa cell layers.5 Antral follicles become acutely dependent on gonadotropins for further growth and development. Follicular growth (from primordial to preantral follicle stage) is continuous. However, less than 1% of primordial follicles present at the time of birth will ever proceed to ovulation, with the majority of follicles degenerating by atresia.6

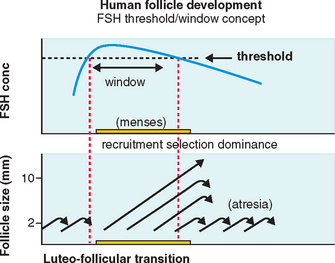

FSH Threshold

FSH concentrations must exceed a certain level before follicular development will proceed.7 When this FSH threshold is surpassed in the normal cycle, the growth of a cohort of small antral follicles is stimulated and ensures ongoing preovulatory follicular development (Fig. 37-1).8 The duration of this period in which the threshold is exceeded (the FSH window) is limited in the normal cycle by a decrease in FSH, which occurs in the early to mid-follicular phase because of negative feedback from rising estrogen levels.

Extending this window would allow the continuous development of more follicles. In the normal cycle, one follicle continues developing despite falling FSH levels because of an increased sensitivity to FSH8 while the remaining follicles respond to falling FSH levels by undergoing atresia, as shown in Figure 37-1.

When the follicle reaches a certain level of development, sustained high circulating levels of estradiol produced by the preovulatory follicle will initiate the midcycle surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) that will trigger ovulation. The surge initiates a gene cascade in granulosa cells, the products of which initiate luteinization, signal the egg to commence meiotic maturation, and lead to rupture of the follicle wall.9

Corpus Luteum Development

The preovulatory LH surge results in luteinization of granulosa and theca cells and alters the steroidogenic pathway so that progesterone is the primary steroid hormone produced after luteinization. However, the corpus luteum retains the ability to produce estrogen. Adequate luteal progesterone is secreted to allow maintenance of pregnancy until a conceptus-derived source of progesterone, the placenta, can produce adequate amounts of this steroid to support pregnancy.10

OVULATION INDUCTION

Ovulatory Dysfunction Classification

Clinically obvious anovulation or oligo-ovulation has been traditionally classified into three groups: World Health Organization (WHO) group I, II, and III anovulation.11

Medications for Ovarian Follicle Stimulation

Gemzell and his coworkers announced the first successful induction of ovulation using human pituitary gonadotropins in 1958 and the first pregnancy in 1960.12,13 One year later, Bettendorf and his group reported a similar experience.14 In 1961, Greenblatt and his coworkers published the first results of ovulation induction achieved by the use of clomiphene citrate (at that time known as MRL/41).15

CLOMIPHENE CITRATE

For more than 40 years, clomiphene citrate has been the most commonly used oral agent for induction of ovulation. Since the early 1960s, results of clomiphene citrate treatment have not changed appreciably, despite the advent of modern immunoassays for steroid hormones, advances in ultrasound technology for cycle monitoring, and the introduction of commercial ovulation predictor kits that allow accurate identification of the midcycle LH surge.

It is interesting to note that clomiphene citrate is considered pregnancy risk category X. Studies in rats and mice have shown a dose-related increase in some types of malformations and an increase in mortality. This is particularly important when considering the relatively long half-life of about 5 days to 3 weeks (depending on the isomer) and that clomiphene citrate may be stored in body fat.16–18 Fortunately, studies in humans have not found an association between clomiphene citrate and congenital defects.

Structure and Pharmacokinetics

Chemically, clomiphene citrate is a nonsteroidal triphenylethylene derivative and is chemically related to diethylstilbestrol and tamoxifen. Like the latter of these compounds, clomiphene can be considered to be a SERM that can exhibit both estrogen agonist and antagonist properties depending on the prevailing levels of endogenous estrogen. Estrogen agonist properties are manifest only when endogenous estrogen levels are extremely low. Otherwise, clomiphene citrate acts mainly as an antiestrogen.16

Clomiphene citrate is cleared through the liver and excreted in the stool. About 85% of an administered dose is eliminated after approximately 6 days, although traces may remain in the circulation for much longer.17 Clomiphene citrate is a racemic mixture of two distinct stereoisomers, enclomiphene and zuclomiphene, having different properties. Available evidence indicates that enclomiphene is the more potent antiestrogenic isomer and the one primarily responsible for the ovulation-inducing actions of clomiphene citrate.16–18

Levels of enclomiphene rise rapidly after administration and fall to undetectable concentrations after few days. Zuclomiphene, the transisomer of clomiphene citrate, is cleared far more slowly; levels of this less active isomer remain detectable in the circulation for more than 1 month after treatment and may actually accumulate over consecutive cycles of treatment.18

Pharmacodynamics and Mode of Action

Clomiphene binds to estrogen receptors throughout the body due to its structural similarity to estrogen. However, unlike natural estrogen, which only binds estrogen receptors for a period of hours, clomiphene citrate binds estrogen receptors for an extended period of time, weeks rather than hours. Such extended binding ultimately depletes estrogen receptor concentrations by interfering with the normal process of estrogen receptor replenishment.15

It is believed that the hypothalamus is the main site of action because in normally ovulatory women, clomiphene citrate treatment was found to increases GnRH pulse frequency.19 However, actions at the pituitary level may also be involved because clomiphene citrate treatment increased pulse amplitude, but not frequency in anovulatory women with PCOS, in whom the GnRH pulse frequency is already abnormally high.20

During clomiphene citrate treatment, levels of both LH and FSH rise, then fall again after the typical 5-day course of therapy is completed. In successful treatment cycles, one or more dominant follicles emerge and mature, generating a rising tide of estrogen that ultimately triggers the midcycle LH surge and ovulation.19,20

Clomiphene Citrate Administration

The effective dose of clomiphene citrate for most women ranges from 50 to 250 mg/day, although some women will be found to be sensitive to clomiphene citrate and only require doses as low as 12.5 to 25 mg/day. Most women will ovulate at the lower doses, with 52% ovulating after 50 mg/day and another 22% after treatment with 100 mg/day. Although higher doses are sometimes required, the ovulation rates are usually low at these doses, with only 12% ovulating after 150 mg/day, 7% after 200 mg/day, and 5% after 250 mg/day. Most women who fail to respond to 150 mg/day of clomiphene citrate will ultimately require alternative or combination treatments.21,22

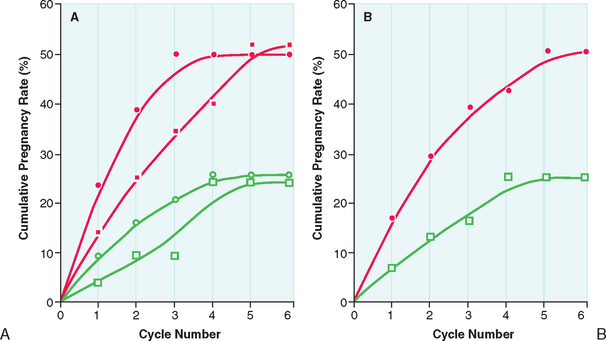

After the lowest ovulatory dose is determined, the same dose is repeated until pregnancy is achieved or a maximum number of approximately six cycles is reached. Pregnancy rates are highest during the first three cycles of clomiphene citrate treatment. The chances of achieving pregnancy are significantly lower beyond the third treatment cycle and uncommon beyond the sixth treatment cycle (Fig. 37-2). Therefore, it is rarely advisable to continue clomiphene citrate treatment beyond six treatment cycles.21

The recommendation regarding which dose to apply is clear in cases of anovulatory infertility (increments of 50 mg until ovulation is achieved, then the dose is maintained). However, this is not clear in cases with ovulatory infertility. There are no adequate studies regarding which dose or what response (number of mature follicles) would be optimal in these women. This uncertainty is related to the individual variability in response to clomiphene citrate treatment irrespective of the dose and to the absence of a clear correlation between pregnancy rates and the number of mature follicles or amount of clomiphene citrate administered. Moreover, the value of clomiphene citrate treatment in enhancing the chance of achieving pregnancy in cases with ovulatory infertility has been questioned22 and has not been proven by large controlled studies.

Treatment Monitoring

Monitoring is required to ensure that ovulation is occurring during a clomiphene citrate treatment cycle. For most patients treated with clomiphene citrate, ovulation monitoring can often be done with any one of a number of low-cost, highly convenient methods conducted in the setting of a general obstetrician and gynecologist practice. Objective evidence of ovulation and normal luteal function are keys to successful treatment. The choice may vary and should be tailored to meet the needs of the individual patient.23

Urinary LH Detection Kit

An ovulation prediction kit can identify the midcycle LH surge in urine and more precisely defines both the interval of peak fertility (day of surge detection and the next 2 days).24 Usually the LH surge is observed from 5 to 12 days after the last clomiphene citrate tablet.25 Ovulation will generally follow within 14 to 26 hours of detection of an LH surge. Consequently, timed coitus or intrauterine insemination (IUI) on the day after the first positive urinary LH test will have the highest pregnancy rates.

Midluteal Progesterone

BBT charts and urinary LH detection kits can confirm that ovulation has occurred but do not document the quality of luteal function, which requires further tests—classically, a serum progesterone determination or endometrial biopsy.

A progesterone level above 3 ng/mL is evidence of ovulation.26 Midluteal phase progesterone concentration (7 days after BBT shift or 7 to 9 days after urinary LH surge) offers more information. Levels exceeding 10 ng/mL are usually suggestive of an adequate luteal phase.27 Endometrial biopsy and “secretory” histology that results from the action of progesterone also provides evidence of ovulation. Endometrial “dating,” using established histologic criteria, has been traditionally suggested for diagnosing luteal phase adequacy.28 However, there is still much uncertainty about the importance of luteal phase defects diagnosed by serum progesterone levels or by endometrial biopsies, reflecting our poor state of knowledge regarding the actual mechanisms involved in endometrial receptivity and implantation.29,30

More sophisticated measures to monitor the outcome of clomiphene citrate treatment, including transvaginal follicular ultrasound scans and measurements of serum estradiol and LH levels, can usually be conducted in a subspecialist reproductive endocrinology practice. Because of the cost and logistic requirements involved, the method is generally reserved for patients in whom less complicated methods fail to provide the necessary information and for women who are at a high risk for developing serious complications such as severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and multiple pregnancy.23

In the past, it was generally recommended that patients receiving clomiphene citrate treatment be examined before starting each new treatment cycle to ensure that there was no significant residual ovarian enlargement or ovarian follicular cysts. However, it appears that small residual follicular cysts usually do not expand during continued treatment.31 Consequently, it is unnecessary to perform “baseline” ultrasound examinations before each new treatment cycle. However, it is reasonable to withhold treatment when symptoms suggest the presence of a large cyst or gross residual ovarian enlargement.23

Outcome of Clomiphene Citrate Treatment

Clomiphene citrate treatment has been reported to successfully induce ovulation in 60% to 80% of properly selected women. More than 70% of those who ovulate respond at the 50-mg or 100-mg dosage level. In young anovulatory women in whom anovulation is the sole reason preventing them from conceiving, cumulative conception rates between 60% and 70% are observed after up to three successfully induced ovulatory cycles, and 70% to 85% after five cycles. Overall, cycle fecundity is approximately 15% in women who ovulate in response to treatment.21

In the reality of daily clinical practice, clomiphene citrate induction of ovulation usually results in much lower pregnancy rates, particularly in a subspecialty referral infertility practice. Important factors that adversely affect treatment outcome are increased age (particularly older than age 35), presence of other treated or untreated infertility factors, and increasing duration of infertility.32 Amenorrheic women are more likely to conceive than oligomenorrheic women, probably because those who already ovulate, albeit inconsistently (oligomenorrheic), are more likely to have other coexisting infertility factors. Generally speaking, failure to conceive within six clomiphene citrate-induced ovulatory cycles is a clear indication to expand the diagnostic evaluation to exclude other factors, change the overall treatment strategy, or both.23

Adverse Effects and Risks of Clomiphene Citrate

Side Effects

Less specific side effects include breast tenderness, pelvic discomfort, and nausea, all observed in 2% to 5% of clomiphene citrate-treated women.33 In addition, there are relatively common reports of premenstrual syndrome-type symptoms in women on clomiphene citrate.34

Congenital Anomalies

There is no evidence that clomiphene citrate treatment increases the overall risk of birth defects or of any specific malformation. Several large series have examined the question and have drawn the same conclusion.35,36 Earlier suggestions that the incidence of neural tube defects might be higher in pregnancies conceived during clomiphene citrate treatment have not been confirmed by more recent studies.37 A small study of pregnancy outcome in women inadvertently exposed to clomiphene citrate during the first trimester also found no increase in the prevalence of congenital anomalies.38

Pregnancy Loss

More than one study has suggested that pregnancies resulting from clomiphene citrate treatment are at increased risk of spontaneous abortion compared to spontaneous pregnancies. A study reviewed outcomes of 1744 clomiphene pregnancies compared to outcomes of 3245 spontaneous pregnancies.39 In this study, pregnancy loss was classified as either clinical if a sac was seen on ultrasound or if it occurred after 6 weeks’ gestation, or preclinical if a quantitative human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) was greater than or equal to 25 IU/L and no sac was seen or abortion occurred earlier. In this study, when preclinical and clinical were considered together, the overall incidence of spontaneous abortion was slightly higher for clomiphene pregnancies than for spontaneous pregnancies (23.7% versus 20.4%). When considered separately, preclinical spontaneous abortions were also increased by clomiphene citrate overall (5.8% versus 3.9%) and for women at least 30 years old (8.0% versus 4.9%), but not for those younger than age 30 (3.7 versus 3.0%). In contrast, when clinical abortions were considered separately, clomiphene citrate did not increase the overall rate (18.0% versus 16.4%), but the rate was increased for women younger than age 30 (15.9% versus 11.2%).

More recent studies looking at rate of spontaneous miscarriage in 62,228 clinical pregnancies resulting from ART procedures initiated in 1996 to 1998 in U.S. clinics also found that spontaneous miscarriage risk was increased among women who used clomiphene citrate.40,41 However, the results of these studies are not considered to be conclusive. The pregnancy loss seen in women after clomiphene treatment may actually be related to other comorbidities in these patients, such as insulin resistance, other genetic factors related to PCOS or unexplained infertility, endometriosis, and advancing maternal age.42

Antiestrogenic Effects and Fertility

These adverse effects are believed to explain the “discrepancy” between the ovulation and conception rates observed in clomiphene citrate-treated patients. These effects appear to be more apparent at higher doses or after longer durations of treatment. It has been suggested that treatment with exogenous supplemental estrogen may help to minimize or negate these effects.43,44 However, there is little compelling evidence to support any beneficial effect of estrogen replacement to reverse these peripheral antiestrogenic effects.23

Clomiphene citrate treatment has been shown to affect the quality and quantity of cervical mucus production as well as the structure of the endometrium.45–47 However, cervical mucus score (based on quantity and quality) has not been found to be of proven prognostic value on the treatment outcome (i.e., achievement of pregnancy).

The endometrium is believed to be one of the most important targets of the antiestrogenic effect of clomiphene citrate and may explain a large part of the lower pregnancy rate and the possible higher miscarriage rate with clomiphene citrate. Successful implantation requires a receptive endometrium, with synchronous development of glands and stroma.48

Studies have reported conflicting effects of clomiphene citrate on the endometrium45–47,49–51 possibly due to different methodology used for endometrial assessment. However, a recent study has prospectively applied morphometric analysis of the endometrium, a quantitative and objective technique to study the effect of clomiphene citrate on the endometrium in a group of normal women. In this study, clomiphene citrate was found to have a deleterious effect on the endometrium, demonstrated by a reduction in glandular density and an increase in the number of vacuolated cells.51 In addition, a reduction in endometrial thickness below the level thought to be needed to sustain implantation was found in up to 30% of women receiving clomiphene citrate for ovulation induction or for unexplained infertility.45 This observation has been confirmed by other studies.46,47

Decreased uterine blood flow during the early luteal phase and the peri-implantation stage has been suggested to explain, at least in part, the poor outcome of clomiphene citrate treatment.51 Other investigators have suggested the presence of other unrecognized factors associated with clomiphene citrate treatment failure.52–54 Moreover, there is some evidence for a direct negative effect of clomiphene citrate on fertilization, and on early mouse and rabbit embryo development.55,56 In addition, there have been reports of low-quality oocytes associated with clomiphene citrate treatment. However, the negative effects of clomiphene citrate in some animal studies have not been confirmed by others,53,54 and at present it is unclear if there are adverse direct effects of clomiphene citrate on human oocytes and human embryo development.

Because of the above-mentioned evidence for adverse peripheral antiestrogenic effects of clomiphene citrate treatment, several investigators tried to reverse these effects by administering estrogen concomitantly with clomiphene citrate treatment. Some investigators have reported increased endometrial thickness and improved pregnancy rates with this approach57,58; others have reported no benefit44 or even a deleterious effect of estrogen administration.59 Another approach has been to administer clomiphene citrate earlier during the menstrual cycle rather than starting on day 5,60 in the hopes of allowing the antiestrogenic effect to wear off to some extent before ovulation and implantation. In view of the long half-life of clomiphene citrate isomers, this approach is unlikely to be successful. A third method has been to combine another SERM such as tamoxifen, which has more estrogen agonistic effect on the endometrium with clomiphene citrate or to use tamoxifen as an alternative to clomiphene citrate.61 However, none of these strategies have proved to be completely successful in avoiding the peripheral antiestrogenic effects of clomiphene citrate. A more recent publication has suggested that high-dose soy isoflavones may be able to overcome the antiestrogenic effect of clomiphene citrate on the endometrium.62 This report remains to be confirmed by other investigators.

To summarize, from the available evidence and accumulated clinical experience, it is difficult to conclude the exact significance of adverse antiestrogenic effects on pregnancy outcome in clomiphene citrate-treated women. It seems that individual variability exists regarding sensitivity to the peripheral antiestrogenic effects of clomiphene citrate, likely because of the complexity of estrogen receptor replenishment and activation, and individual differences in the pharmacokinetics of clomiphene citrate. The discrepancy in the success rates in achieving pregnancy between women with unexplained infertility and women with PCOS in response to clomiphene citrate treatment (higher rates in PCOS women) suggests that PCOS women may be less vulnerable to the antiestrogenic effects of clomiphene citrate on peripheral tissues. Recent findings of differences in the expression levels of receptors (androgen receptor, estrogen receptor α and β, progesterone receptor) and cofactors in human endometrium and myometrium in PCOS patients support this hypothesis.63 For example, the p160 family of steroid receptor coactivators, known to facilitate the action of steroid receptors throughout the menstrual cycle, was found to be overexpressed in the endometrium of women with PCOS.80 However, the presence of infertility factors, rather than an increased sensitivity to the antiestrogenic effects of clomiphene citrate, in non-PCOS women may explain the less favorable outcome of clomiphene citrate treatment.

FAILURE OF CLOMIPHENE CITRATE TREATMENT

Etiologies

Clomiphene Pregnancy Failure

The reasons for clomiphene pregnancy failure (women who ovulate in response to clomiphene citrate but do not achieve pregnancy) may be related to a wide variety of underlying infertility factors, such as male factor infertility, endometriosis, undiagnosed tubal factor, or endometrial receptivity factors. However, the success of many of these women in achieving pregnancy with alternative ovarian stimulation protocols using injectable gonadotropins or aromatase inhibitors supports the hypothesis that persistent antiestrogenic effects associated with clomiphene citrate might play a major role in the discrepancy between ovulatory rates and pregnancy rates.64–66

ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES FOR CLOMIPHENE FAILURES

Some women who are refractory to standard clomiphene citrate treatment regimens will ovulate in response to alternative regimens of clomiphene citrate, including longer duration or higher doses of clomiphene citrate treatment. For example, an 8-day treatment regimen or doses of 200 to 250 mg/day can be effective when shorter courses of therapy fail. However, longer treatment and higher doses are expected to be associated with more antiestrogenic effects and reduced chances for achieving pregnancy even though ovulation is achieved.23

Insulin-Sensitizing Agents

Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are recognized features of PCOS. Hyperinsulinemia contributes significantly to hyperandrogenism and chronic anovulation. It is logical that agents that improve insulin action in the body (insulin sensitizers) will help infertile PCOS women with insulin resistance to achieve ovulation by lowering their hyperinsulinemia. This is particularly true in PCOS patients who fail to ovulate with clomiphene citrate treatment. De Leo and colleagues reviewed the use of insulin-lowering agents in the management of PCOS,67 with extensive discussion of the effect of these agents on endocrine, metabolic, and reproductive functions.

Although it is believed that the endocrine and reproductive benefits observed during treatment with insulin sensitizers in PCOS women are due to improving insulin resistance, insulin sensitizers may work through other mechanisms to achieve ovulation in these patients. One such mechanism is a direct effect on ovarian steroidogenesis. There is evidence that the insulin sensitizers, metformin and thiazolidinediones, can modulate steroid production through direct suppression of steroidogenesis enzymes. Troglitazone was found to inhibit progesterone production by human luteinized granulosa cells and to reduce androgen production by rat theca cells.68,69 It was also found to directly inhibit 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, leading to decreased progesterone secretion by porcine granulosa cells.70 Troglitazone, and presumably other thiazolidinediones, inhibits cholesterol biosynthesis in Chinese hamster ovary cells71 and aromatase in human granulosa cells.72

Metformin

Several studies demonstrated that treatment alone with the insulin-sensitizing agent metformin could restore menses and cyclic ovulation in many amenorrheic PCOS women.16,73 This led some to advocate metformin as primary therapy in infertile PCOS women with insulin resistance (1000 to 2000 mg/day in divided doses) and add clomiphene citrate only in those who fail to respond. However, the relatively greater costs per cycle compared to clomiphene citrate, as well as the complexity of metformin treatment and the frequency of significant gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) made others prefer to reserve metformin treatment for those who first prove resistant to clomiphene citrate. Caution should be used in prescribing these drugs to women with potential renal or liver disease. It is recommended that a creatinine level and liver function tests be obtained before starting therapy.73

Unfortunately, most of the studies published so far on the use of metformin in PCOS women were not randomized. Even the randomized trials included a small number of patients, which prevented definitive conclusions. However, meta-analysis of the combined results of prior clinical trials concluded that metformin is effective in achieving significant rates of ovulation and pregnancy in women with PCOS. It is important to note the difference between achieving ovulation and achieving a pregnancy.

Effectiveness of Metformin

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis showed that metformin is effective in achieving ovulation in women with PCOS with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.88 (confidence interval [CI], 2.25–6.69) for metformin versus placebo and 4.41 (CI, 2.37–8.22) for metformin and clomiphene citrate versus clomiphene citrate alone. An analysis of pregnancy rates suggests a significant treatment effect for metformin and clomiphene citrate (OR, 4.40; CI, 1.96–9.85). The authors concluded that metformin is an effective treatment for anovulation in women with PCOS, and its choice as a first-line agent seems justified.73

A more recent systematic review of metformin use in women with PCOS included cohort and randomized, controlled trials of metformin versus placebo, metformin versus clomiphene citrate, and metformin plus clomiphene citrate versus placebo plus clomiphene citrate. The authors found metformin to be 50% better than placebo for ovulation induction (RR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.13–1.99). However, metformin alone was not of confirmed benefit versus placebo for achievement of pregnancy (RR, 1.07; CI, 0.20–5.74) whereas metformin plus clomiphene citrate was threefold superior to clomiphene citrate alone for ovulation induction (RR, 3.04; CI, 1.77–5.24) and pregnancy (RR, 3.65; CI, 1.11–11.99). The authors concluded that metformin is effective for ovulation and metformin plus clomiphene citrate appears to be very effective for achievement of pregnancy compared to clomiphene citrate alone.74 In a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial comparing clomiphene citrate and metformin as the first-line treatment for ovulation induction in nonobese anovulatory women with PCOS, it was shown that metformin 850 mg twice daily was associated with a higher pregnancy rate than clomiphene citrate 150 mg for 5 days from the third day of a progesterone withdrawal bleed (69% versus 34%).75 There was also a tend toward a higher birth rate. In a recent multicenter randomized placebo controlled trial, it was shown that metformin did not increase the probability of ovulation or pregnancy when added to clomiphene citrate as a first-line treatment of infertile women with PCOS.76 Therefore, in most cases clomiphene citrate is considered the drug of choice in the treatment of anovulatory infertility of PCOS. Metformin can be added if clomiphene fails to induce ovulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree