Fig. 17.1

Gastrografin enema demonstrating a pouch-vaginal fistula

MRI Pelvis

This is a good test for the evaluation of abnormalities relating to the structure of the pouch and pelvis and the identification of any persistent presacral collections, abscesses, or fistulae that could be contributing to the patient’s symptoms. Pelvic sepsis due to chronic leaks related to the pouch or suture and staple lines may be responsible for indolent infection in the presacral space, which may manifest as low- or high-grade sepsis and poor pouch function.

CT Enterography

This is a good test for the evaluation of the condition of the small intestine proximal to the pouch and especially helps to clarify the presence or absence of inflammatory bowel disease, particularly in the setting of underlying Crohn’s disease that can lead to strictures or fistulae. Pelvic abnormalities related to the pouch and the state of the perineum and associated abnormalities can also be assessed.

Tests of Anorectal Physiology

Anorectal manometry evaluates resting and squeeze tone of the sphincter mechanism. The presence of paradoxical pressures, when correlated with difficulties with evacuation, may confirm outlet obstruction that is either organic or functional.

Endorectal ultrasound helps assess the integrity of the sphincters in patients with incontinence.

EMG/pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML) testing may help identify a neuropathy or sphincter dysfunction, though are often not as useful in this setting.

A defecating pouchogram identifies any problems with evacuation.

Surgical Decision-Making

Key Concept: The majority of patients undergo a multistage procedure to mitigate the risk of pouch problems from an unprotected pouch anastomotic leak.

As previously discussed, certain perioperative complications likely influence long-term pouch outcomes and function. Thus, avoiding such complications may preserve function over the long term. The ability to stage the proctocolectomy and IPAA allows for the gradation of the severity of surgical insult, and thus, the choice of the extent of the procedure can be individualized for each patient, depending upon anticipated outcomes. While suitable patients who are well nourished, of average build with mild colitis, and not on immunosuppression may be candidates for a one-stage pouch procedure, this is rarely employed in our practice. Although a one-stage operation may minimize the cumulative influence of multiple operations, in terms of complications and risks, a leak from an unprotected anastomosis may have devastating complications, including loss of the pouch. We hence very selectively perform a single-stage restorative proctocolectomy, and the majority of even such good-risk patients undergo a two-stage restorative proctocolectomy where the IPAA is defunctioned by a proximal loop ileostomy (Fig. 17.2). For patients who are sicker, more malnourished, with severe colitis, or under treatment with large doses of steroids and immunosuppression, a three-stage procedure is chosen since this likely minimizes complications. The rationale for such an approach is that an initial colectomy with an end ileostomy eliminates the inflamed colon without adding the risk of an intestinal anastomosis when tissues are still inflamed and nutrition is inadequate. This strategy also allows pelvic dissection to be deferred until the rectum is less inflamed, since this minimizes the potential risk of injury to the pelvic nerves. An initial subtotal colectomy is also a good option in patients with a suboptimal body mass index (BMI), since this allows for the institution of nutritional intervention and exercise to optimize weight prior to IPAA creation.

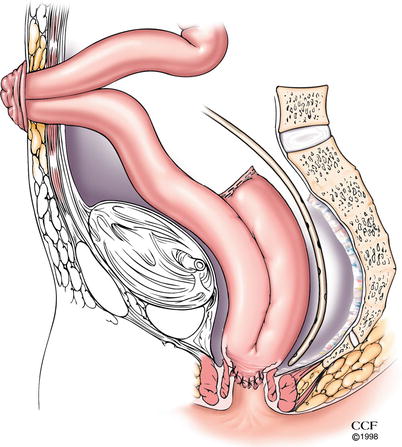

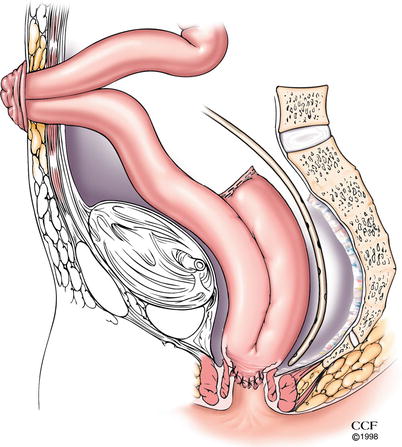

Fig. 17.2

Ileal J-pouch-anal anastomosis with defunctioning loop ileostomy (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2012. All Rights Reserved)

Intraoperative Challenges During Ileoanal Pouch Creation and Anastomosis

Key Concept: Several potential technical challenges, ranging from achieving a tension–free anastomosis to inducing an iatrogenic fistula, are present during pouch construction that you need to be aware of and have a plan to overcome or avoid altogether.

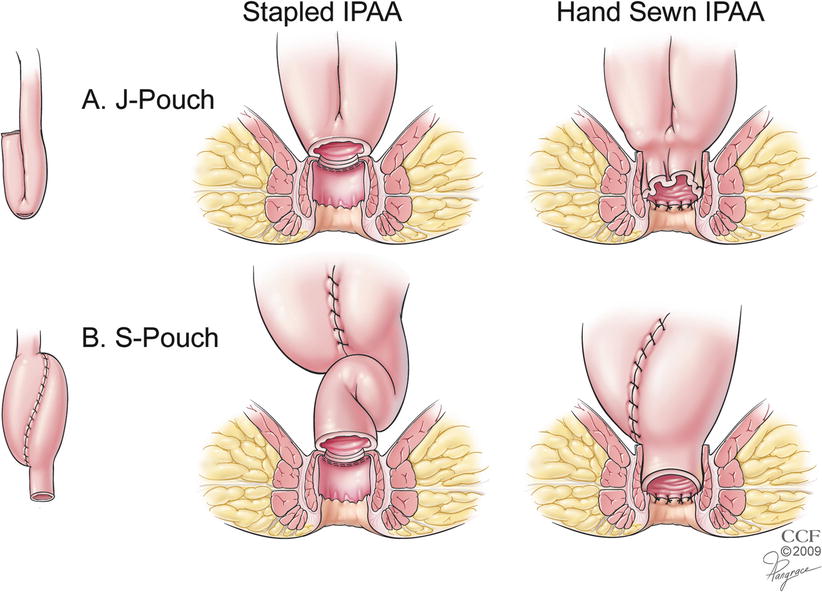

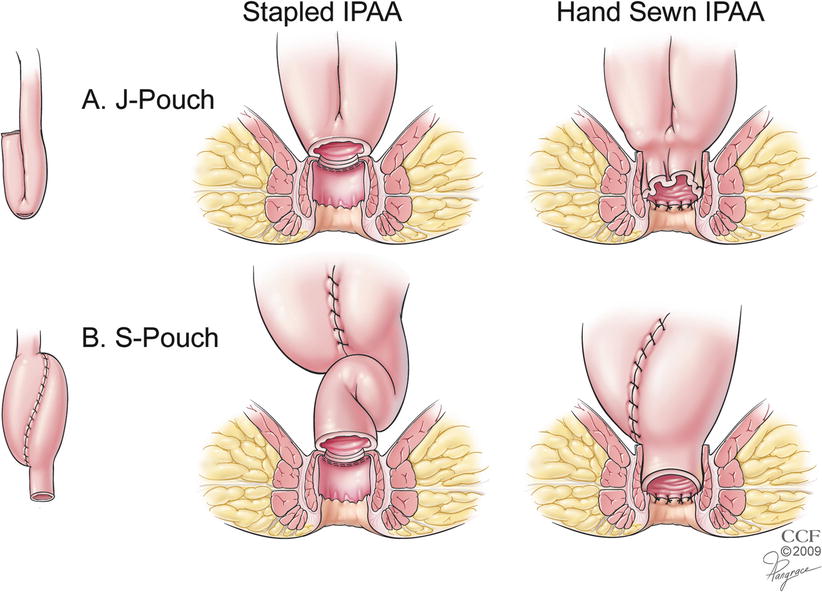

Commonly employed options with regard to pouch configuration and anastomosis include a J or S pouch and a stapled or hand-sewn anastomosis (Fig. 17.3). Our current preference for a primary ileoanal pouch is a J pouch 20 cm long with a stapled IPAA. The option of mucosectomy with a hand-sewn anastomosis is in general reserved for specific circumstances such as for a redo IPAA, colitis with high-grade dysplasia or cancer involving the distal rectum, or when patients with FAP have extensive carpeting of the distal rectum with polyps. During IPAA creation, close attention needs to be directed towards the avoidance of anastomotic tension, maintenance of appropriate orientation and blood supply of the pouch and the residual anorectum, and the avoidance of the incorporation of the vagina/prostate and seminal vesicles in the staple line.

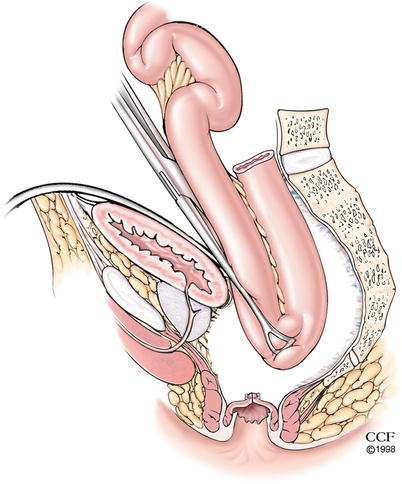

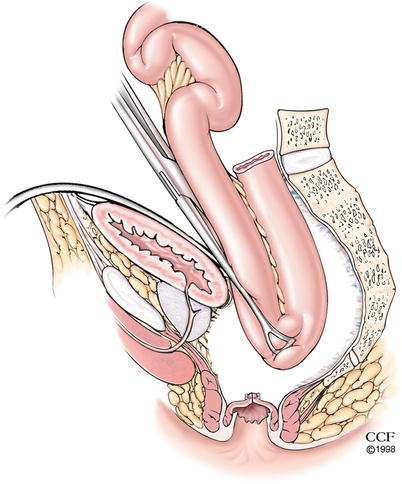

Fig. 17.3

(a, b) Commonly used pouch configurations and anastomoses (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2012. All Rights Reserved)

Problems with Reach of the Pouch

Key Concept: Prior to transecting the rectum, evaluate for potential problems with length, and when there is an issue, proceed through a series of maneuvers to ensure a tension-free anastomosis.

The length and orientation of the small bowel and the anatomy of the pelvis and mesentery are variable in different patients. Thus, difficulty with reach of the pouch to the anal canal for an anastomosis is expected in some circumstances. Tall patients and those with a high BMI are particularly at risk. Thus, weight loss before surgery may be helpful. In the operating room, various maneuvers may be employed to facilitate reach. High ligation of the ileocolic vessels, release of the small bowel mesentery from the retroperitoneum, mobilization of the duodenum, excision of the redundant mesenteric tissue lateral to the superior mesenteric vessels (“jib-sail”), and performing releasing incisions along the mesenteric edge of the small intestine also facilitate reach of the pouch to the anal canal. Although ligation of some of the branches of the SMA (or the main trunk of the SMA) has also been described, we rarely employ this maneuver due to the risk for compromise of blood supply to the entire small intestine.

Difficulty with reach of the pouch to the anal canal can be anticipated before rectal transection during proctectomy and the operation accordingly modified to promote the chance for a successful IPAA. Prior to transaction of the rectum, an IPAA can be simulated with the most dependent portion of the pouch held in a Babcock forceps that is delivered into the pelvis. A bimanual palpation with the gloved finger passed into anal canal prior to IPAA helps confirm reach of the Babcock to the intended level of division of the rectum (Fig. 17.4). In certain circumstances, such as patients with a high BMI, difficulties with reach of the pouch to the anal canal may persist. In this, and other similar instances, the rectal stump may be intentionally left slightly long to minimize tension on the IPAA. Orienting the pouch in such a way as to direct the mesentery to lie in an anterior location during anastomosis may also allow for the release of tension that may be present with a pouch with a posteriorly oriented mesentery. When these efforts fail, consideration may be given to the creation of an “S” instead of a “J” pouch since this provides an extra 2 cm of reach of the pouch for anastomosis to the anal canal when compared to the other pouch configurations (Fig. 17.5). In the rare circumstance where the pouch has been created and cannot be anastomosed to the anal canal, leaving the closed pouch hitched to the pelvis with a proximal defunctioning ostomy has been described as a maneuver that allows the pouch to lengthen with time.

Fig. 17.4

Evaluating reach of the pouch to the anorectal stump (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2012. All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 17.5

Configuration of the pouch. The S pouch provides an extra 2 cm of reach to the anal canal (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2012. All Rights Reserved)

Ischemia of the Pouch

Key Concept: Avoid overaggressive dissection of the pouch blood supply or inadvertent pouch rotation that may result in devascularization or kinking of the arterial inflow to the pouch and resultant ischemia.

This is a rare occurrence and is usually related to an overzealous skeletonization of the blood vessels that supply the pouch or damage to the blood supply of the pouch by direct injury or traction due to tension. Additionally, inadvertent twisting of the pouch as it is brought down into the pelvis can block arterial blood flow to the pouch. When ischemia occurs, pouch excision with the creation of a new pouch with an additional length of small intestine proximal to the pouch can be undertaken. This, however, may sometimes be associated with difficulty of reach of the pouch to the anal canal.

Problems with Stoma Creation

Key Concept: Certain patients may be expected to have difficulties with diversion and you should have a plan ahead of time to deal with this situation.

The defunctioning ileostomy can be difficult to create in patients who have had difficulty with reach of the pouch or those with a high BMI. Creation of the ostomy in a more proximal portion of the small intestine in these circumstances minimizes tension on the IPAA. This can, however, be associated with a high ostomy output and thus requires the careful monitoring of volume of output and fluid and electrolyte balance with the concomitant use of bowel stoppers until ostomy closure. While in many cases this may be unavoidable, anticipating diversion difficulties and discussing potential strategies to alleviate them with the patient will allow for realistic expectations. This may include mandating weight loss prior to surgery, trading off the ideal location of the stoma for one that is functionally better, using an end-loop versus a loop stoma, or instituting a medical regimen early to slow effluent and improve absorption.

Problems with the Anastomosis and Stapler Misfire

Key Concept: Mechanical difficulties with a stapler may be managed with a redo stapled or conversion to a hand–sewn anastomosis. You must ensure adequate length is available to avoid tension at the anastomosis.

Problems associated with the anastomosis and stapler misfire that occur in the operating room can be disheartening; however, the situation is usually salvageable. The surgeon needs to ensure adequate assistance to facilitate retraction and exposure so as to allow access to both the abdomen and perineum. The specific management depends upon the type and severity of the problem encountered. For a small anastomotic dehiscence that is identified on air testing, the creation of a defunctioning ostomy either alone or in addition to suture approximation of the defect by the abdominal or perineal approach may be all that is required. On the other hand, for a major breach of the anastomosis, when nonfunction or malfunction of the stapler occurs or when the anal cuff staple line is breached by the inserted stapler, the anastomosis may have to be redone. In these circumstances, disconnection of the IPAA followed by an assessment of the structure and reach of the pouch, as well as the length and condition of the residual anal canal, is performed. Provided there is an adequate length of the rectal cuff remaining above the anorectal ring, a purse-string suture can be manually placed on the cuff and is then tied around the stapler that is introduced transanally. This allows for the stapled anastomosis to be redone. This is often very difficult and, in many cases, impossible to do. Therefore, when this is not feasible, a hand-sewn anastomosis should be performed between the pouch and the residual anal canal, often after the incorporation of additional maneuvers to mobilize the pouch to ensure adequate length.

Management of Surgical Complications Related to the Pouch

Early Complications

As previously discussed, some of the complications, especially those related to the anastomosis and pelvic sepsis, may affect the long-term function of the pouch. Thus, the prompt identification of these complications and their management is required so as to preserve a functional pouch.

Anastomotic Disruption and Pelvic Abscess

Key Concept: Whether through a transanal, transabdominal, or trans–anastomotic route, prompt drainage of pelvic abscesses (often along with appropriate diversion) is crucial to preserving pouch function.

These conditions are often interrelated. An anastomotic disruption may be isolated or associated with sepsis and may be silent or present with pelvis sepsis and abscess. Patients with a pelvic abscess usually present with fever, leukocytosis, and other signs of infection or sepsis. However, the findings may sometimes be indolent and manifest as a persistent ileus or prolonged recovery in the postoperative period. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with oral, intravenous, and rectal contrast helps delineate the presence and location of any abscess and any associated anastomotic leak. Hemodynamic instability and peritonitis mandate an exploratory laparotomy with peritoneal washout and the creation of an ostomy when the pouch was not defunctioned at IPAA. Conversion of a loop ileostomy above a pouch to an end ostomy allows for complete diversion of enteric contents from the pouch and may occasionally be required. In stable patients, the prompt institution of percutaneous drainage of any identified abscesses and treatment with intravenous antibiotics allows for the control of sepsis and may minimize long-term ill-effects on the pouch due to persistent sepsis.

When a pelvic abscess or presacral collection is detected after IPAA, prompt surgical drainage of the abscess with eradication of sepsis may help conserve the pouch. When such abscesses are associated with an anastomotic leak detected on CT scan, whether drainage should be by the transanal route or by percutaneous CT-guided drainage is often a dilemma. A transanal/trans-anastomotic drainage of the abscess through the breached suture or staple line may be more comfortable for the patient and takes advantage of the conditions already present. However, whether a trans-anastomotic drain interferes with anastomotic healing and, consequently, pouch retention is a potential concern. In contrast, CT-guided drainage may be more uncomfortable and be associated with concerns for the development of an extrasphincteric fistula. The results of a review of our experience [9] with 71 patients suggest that pouch failure is high for patients with pelvic abscess associated with an anastomotic leak, but the success rates for the transanal and percutaneous drainage procedures in terms of long-term pouch retention (75.5 and 83 % respectively) and pouch function are similar. Thus, management of the patients needs to be individualized based on a determination of the relative ease and efficacy of the two procedures and the comfort of the patient based on the location and size of the abscess and the anastomotic defect.

Postoperative Bleeding from the Pouch

Key Concept: Identify staple line bleeding during pouch construction. For those manifesting in the postoperative setting, endoscopic control is diagnostic and therapeutic.

This complication can be minimized by inspecting the back row of staples aligned along the mesentery of the small bowel after the pouch has been created. Our practice is to oversew any bleeding areas that are identified in the staple line with interrupted sutures placed in a figure-of-eight fashion. When bleeding occurs postoperatively, this may manifest as bleeding through the anal canal or into the ileostomy. Pouch endoscopy with cauterization of any identified bleeding points or the application of hemostatic clips or injection of epinephrine usually controls bleeding. When there is diffuse oozing, the instillation of ice-cold saline with epinephrine into the pouch facilitates control of bleeding [10].

Late Complications

Many of these late complications manifest following takedown of the ileostomy and restoration of stool through the pouch.

Pouch-Vaginal Fistula (PVF)

Key Concept: While investigative studies are available to help guide treatment, EUA is the gold standard for evaluating PVF. Management options range from local options with or without diversion to redo IPAA.

This complication is potentially disabling and can cause significant impingement on quality of life. However, its presentation and the extent of its effect vary among patients. Common symptoms include discomfort, irritation, incontinence, as well as recurrent vaginal and urinary infections.

Investigations

These are chosen so as to assess the size, nature, and location of the fistula; state of the anoperineum and sphincter mechanism; configuration, size, and state of the pouch; and the presence or absence of any associated disease of the small intestine. The potential diagnosis of Crohn’s disease needs to be considered in any patient who develops fistulous and septic complications after IPAA, since this determines the management and also the eventual outcomes. Differentiating septic complications related to IPAA creation from Crohn’s disease is important; however, this is often easier said than done. It is especially difficult when distinct clinical and histopathological features of Crohn’s disease are absent. In general, septic complications that occur within 1 year of IPAA creation or closure of a defunctioning ostomy are likely to be due to perioperative IPAA complications. On the other hand, their occurrence after 1 year of IPAA construction suggests the possibility of a diagnosis change to Crohn’s disease when the initial diagnosis was ulcerative or indeterminate colitis.

A thorough review of the history and medical records relating to the IPAA surgery and the postoperative course is required since this may provide insight into the potential differential diagnoses that may have caused the fistula. A review of pathology relating to the biopsies, even prior to surgery and of the colectomy or proctocolectomy specimen, additionally helps assess the possibility of Crohn’s disease as the correct diagnosis. General, abdominal, and perineal examination for clinical harbingers of Crohn’s disease and evaluation of the tone of the sphincter at rest and with squeeze provide useful information. Vaginoscopy and pouchoscopy may allow for the identification of the fistula and an assessment of the location, number, nature, and size of any fistula as well as the physical state of the pouch, anal canal, and vagina. Examination under anesthesia provides excellent information and is currently the gold standard test in the evaluation of a pouch-vaginal fistula. As stated previously, other tests that should be considered include gastrografin enema, vaginogram, and MRI of the pelvis since these help to further characterize the anatomy of the fistula. CT or MR enterography also helps delineate the anatomy of the pouch and the state of the small bowel above the pouch (Fig. 17.6).

Fig. 17.6

Gastrografin study demonstrating a pouch-vaginal fistula with contrast filling both structures

The final decision relating to the management of the pouch-vaginal fistula depends upon the severity of the symptoms and their effect on the patient’s quality of life (QOL). Examination under anesthesia allows for a better assessment of the fistula tract and the state of the associated tissues. If there is evidence of active inflammation, sepsis, and induration in the tract or adjoining abscess cavity and surrounding tissues, the placement of a seton allows for the reduction in the ongoing sequestration of infection and further damage of tissues. The seton also allows for the normalization of the tissues so that a better assessment of the area may subsequently be feasible. Adequate drainage also allows for the tissues surrounding the fistula to become healthy, with an improvement in the elasticity and tensile strength of anorectal and pouch-related tissues that may be utilized in the definitive repair of the pouch-vaginal fistula. The additional use of medical treatment with antibiotics, anti-inflammatory agents, and anti-Crohn’s disease medication may be required to reduce inflammation before the consideration of repair, especially for those involving local procedures.

Some patients with pouch-vaginal fistulae are candidates for perineal procedures. A redo IPAA is an option when repair by the perineal approach is unlikely to be successful or when local procedures have failed. Although there is a relatively high risk for pouch failure for patients with a pouch-vaginal fistula, up to 85 % of pouch-vaginal fistulae can be healed using these approaches [11–14].

Treatment Options for PVF

Local Procedures

These include pouch or vaginal advancement flap repairs, perineal pouch advancement, fistula plugs, and gracilis flap repair. Local repair may be considered for low, simple fistulae that are not associated with florid inflammation.

Advancement Flap Repair

Technique: We prefer the prone jackknife position in the operating room, with the patient under general anesthesia and skeletal muscle relaxation to provide the best exposure to the area. The procedure is covered with intravenous antibiotics, and a Foley catheter is placed into the bladder. Although the Lone Star Retractor SystemTM (CooperSurgical Inc, Trumbull, CT) is an option for anoperineal exposure, our preference is the placement of effacement sutures in the four quadrants of the perineum, which provide equivalent exposure to the anal verge and canal. A Hill-Ferguson retractor introduced into both the vagina and anal canal facilitates exposure of the fistula tract. A malleable probe such as a lacrimal probe or instead a Lockhart-Mummery probe facilitates identification of the tract. If there is no evidence of festering sepsis and the surrounding tissues are supple and noninflamed, consideration may be given to the creation of a flap for repair. The os of the fistula on the side of the pouch is circumscribed, and a U-shaped curvilinear broad-based flap incorporating the mucosa and submucosa of the pouch wall is raised with the os at its apex. The fistula tract is dissected into the pouch-vaginal septum and excised. The tissue surrounding the excised fistula tract is approximated using #2-0 Vicryl sutures with sutures that incorporate the sphincter mechanism. The flap is developed upwards and sutured to the pouch-anal mucosa, the sutures placed in such a way as to incorporate the adjoining sphincter mechanism on their deep aspect, ensuring a tension-free repair. Our preference is to keep patients on strict bed rest in the hospital for the first 24 h after the procedure. The Foley catheter is discontinued on the second postoperative day and limited mobility of the patient to the bathroom allowed until the return of bowel function. The use of preoperative bowel preparation delays the return of bowel function. Patients are usually discharged on oral antibiotics.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree